|

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

"It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it."

—Robert E. Lee, Fredericksburg, 1862

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania: the most contested ground in America—the bloodiest landscape on the continent. No place more vividly illustrates the intensity of the civil war that engulfed America politically, socially, and physically. Here, competing visions for a nation came to violence. Here a typical American community suffered war in all its forms, and was transformed.

Located midway between the Confederate capital of Richmond and the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C., the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers offered the Confederates opportunities for defense and posed a major obstacle to advancing Union armies. Over 18 months, the Union army staged at least three major campaigns across the rivers near Fredericksburg, resulting in four battles: Fredericksburg (December 1862), Chancellorsville (May 1863), and Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House (May 1864). Together, they caused over 105,000 casualties.

Each campaign balanced on high-stakes, fragile calculations. Each reverberated across the American landscape—to the seats of government in Washington and Richmond, to sitting rooms North and South. The one-sided nature of the defeat at Fredericksburg staggered the Union war effort just weeks before President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. From the stunning victory at Chancellorsville, Southerners took hope that Lee and his army might forge victory—a hope soon dimmed at Gettysburg. A year later, the immense casualties at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House challenged the will of both sides to continue. The war became not a question of tactics, but endurance.

These calamitous dramas played out on a landscape that was home to families, farmers, tradesmen, merchants, and slaves. For slaves, war and the arrival of the Union army meant freedom. For white residents, war brought anguish. Continuous occupation and tumultuous battles left the region devastated. It would take most of a century to recover.

Today the battlefields are quiet, and it is difficult to grasp that here, within a radius of 17 miles, four horrendous battles were fought. The National Park Service is committed to preserving and protecting these treasured landscapes so visitors can experience and gain an understanding of the ground where men clashed in this great defining event of American history.

Confederate and Union Leadership

Leadership was a critical factor in all four battles. By the war's second year, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson emerged as the most famous—and successful—Confederate commanders. The Union Army suffered through a series of inept leaders. Ambrose E. Burnside failed at Fredericksburg and Joseph Hooker lost at Chancellorsville. It wasn't until 1864 that Ulysses S. Grant and George G. Meade finally launched an offensive that marked the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

December 11-13, 1862

Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg: Confederates victorious, a town devastated, a Union army humiliated.

On December 11, 1862, Union troops bombarded the town from Stafford Heights, then crossed the river on pontoon bridges to confront Robert E. Lee's Confederates holding fortified high ground to the west. On December 13, Ambrose E. Burnside's Union troops launched a two-pronged attack. On the south end of the line, they achieved a brief-but-bloody breakthrough against Thomas J. ("Stonewall") Jackson's corps at Prospect Hill. To the north, behind town, waves of Union attackers struggled against the powerful Confederate defenses on Marye's Heights and in the Sunken Road. The result was a resounding Confederate victory that left the fields around Fredericksburg blanketed with Union dead and wounded.

The battle dealt a painful blow to the Union war effort—discouraging Union soldiers and intensifying public debate about the war and the wisdom of emancipation. For the Confederates, the triumph helped establish both Lee and his army as the Confederacy's greatest hope for ultimate victory.

Chatham

Chatham was built by William Fitzhugh between 1768 and 1771 and stood at the center of a plantation that at one time contained nearly 1,300 acres. During the Fredericksburg Campaign the house served as a Union headquarters and telegraph communications center. A hospital was also established here to treat casualties from the battle.

April 27-May 6, 1863

Chancellorsville

At Chancellorsville Robert E. Lee won his greatest victory, but lost his legendary subordinate, Stonewall Jackson.

In May 1863 Union Gen. Joseph Hooker tried to squeeze Lee's army between Union forces advancing from both Fredericksburg, to the east, and Chancellorsville, to the west. Lee confronted Hooker at Chancellorsville, where the Union army formed a powerful defensive line. The night of May 1, the Confederates discovered the Union right flank was vulnerable.

On May 2 Jackson marched 12 miles around the Union army and destroyed Hooker's right wing in a celebrated surprise attack. In the confusion after dark, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own troops. Lee pressed his advantage on May 3, producing perhaps the bloodiest morning of the war. The Federals eventually retreated across the river to safety. Faced with another battlefield disaster, President Lincoln moaned, "My god! What will the country say?"

Stonewall Jackson died on May 10 of pneumonia as a result of his wounds. Despite his death, the Confederates were sustained by back-to-back victories. In June 1863, Lee went on the offensive northward to Pennsylvania—to a place called Gettysburg.

The Chancellor house, which gave Chancellorsville its name, was for much of the battle General Hooker's headquarters. An artillery shell that struck a porch pillar stunned the Union commander, impairing his ability to direct the battle. That morning the building caught fire. Union soldiers rescued Chancellor family members who had taken cover in the cellar. But many wounded soldiers died in the flames.

May 5-6, 1864

The Wilderness

This, the first clash between Grant and Lee and the first major battle for their armies after Gettysburg, began 11 months of nearly continuous combat that decided the war in Virginia.

Ulysses S. Grant directed all Union armies, but attached himself to the Army of the Potomac. "Lee's army will be your objective point," Grant told army commander George G. Meade. "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also." Meade obliged. Their first collision: in the Wilderness.

On no American battlefield did the landscape do more to intensify the horror of combat. For two days the armies grappled in the dense thickets and tangled undergrowth of the Wilderness. The fighting, which began in Saunders Field, focused along the two main roads that pierced the gloom. Each side nearly achieved victory, but in the end the Wilderness won. The fighting ended in a ghastly, fiery stalemate.

Unlike his predecessors, Grant ignored stalemate. Mindful that his campaign would help decide the 1864 presidential election, he forged on. The night of May 7, 1864, the Union army headed south, toward Spotsylvania Court House, toward Richmond. In the darkness, Grant's soldiers cheered. They knew there would now be no turning back.

May 8-21, 1864

Spotsylvania Court House

To those who were there, the tumultuous Battle of Spotsylvania Court House embodied all the horrors of civil war.

From the Wilderness, both armies raced south toward the vital crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, which controlled the most direct route to Richmond. Lee arrived first on May 8 and narrowly beat back Union attackers. Confederates built a bulging line they called the "Mule Shoe" salient. Union attacks tested the Confederate line for several days.

On May 12, Grant struck the tip of the Mule Shoe and broke through. Lee's Confederates counterattacked, and for the next 22 hours the two sides locked in the war's most intense hand-to-hand and close combat. This desperate fighting raged over a bend in the Confederate trenches called the "Bloody Angle." Lee bought enough time to build a new line of earthworks, which he held until Grant abandoned the field on May 21.

At Spotsylvania Grant sought a decisive battlefield victory, but Lee skillfully denied him. Still, the Federals' constant hammering took its toll on dwindling Confederate resources. What began in the Wilderness and Spotsylvania continued on to the North Anna River, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and finally Appomattox Court House.

Fredericksburg National Cemetery

The War Department established this cemetery in July 1865 and reinterred Federal dead from area battlefields, camps, and hospital sites. The cemetery is on Marye's Heights, the Confederate position that proved so impregnable during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Ironically, some men buried here died trying to capture this very ground on December 13, 1862.

Of the over 15,000 Union soldiers buried here, most are unknown. Confederate soldiers are buried in Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Confederate cemeteries.

Exploring the Park

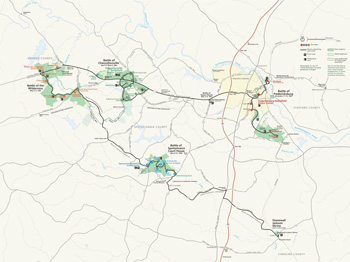

(click for larger map) |

Whether you have two hours or two days to spend here, we recommend beginning at the Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitor Center on Lafayette Boulevard (Business U.S. 1) at the foot of Marye's Heights. Films and exhibits interpret the battlefields. Park historians are on duty here and at Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitor Center on Route 3 to help you plan a rewarding visit.

A complete tour of the park covers over 70 miles and includes the most important sites on all four battlefields. Each battlefield tells its own story. You need not see them all in one day; in fact, we recommend that you don't try to do so. Instead, pick one or two and take time to study the roadside exhibits, sample one of the many interpretive trails, or attend a program led by park historians. Four historic buildings—Ellwood, Old Salem Church, Chatham, and Stonewall Jackson Shrine—are staffed on varying schedules throughout the year.

For Your Safety Driving tours require turning onto and off of busy roads. Hiking, jogging, and bicycling are encouraged here and motorists must be alert to these activities. Beware of stinging insects and poisonous plants. Wear sturdy walking shoes on trails and be alert for hazards.

Accessibility The first floors of Chatham, Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitor Center, and Stonewall Jackson Shrine are wheelchair-accessible. The Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitor Center is accessible to wheelchairs. Service animals are welcome.

Regulations Relic hunting or possessing metal detectors on park property is forbidden. • Firearms are prohibited inside federal facilities; otherwise possession of firearms must comply with applicable federal and Virginia laws. • Climbing on cannon, monuments, earthworks, or historic ruins is forbidden. • Hunting, trapping, spotlighting, or intentionally disturbing wildlife is forbidden. • Cutting or gathering firewood is prohibited. • Picnic only in designated areas. • Consuming and/or possessing alcoholic beverages is prohibited. • All vehicles, including bicycles, must stay on roads open to the motoring public. • Pets must be leashed. They are not permitted in the national cemetery.

Fredericksburg, December 11-13, 1862

Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitor Center The visitor center contains museum displays, a bookstore, and a film explaining the battle. Walking tours of the area of heavy combat on the Sunken Road and Fredericksburg National Cemetery begin here. A self-guiding driving tour of the park also starts here.

Chatham (Park Headquarters) Built 1768-1771, this house served as a Union headquarters and hospital. Famous visitors to the house included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Clara Barton, and Walt Whitman.

Lee's Hill From this hill, called Telegraph Hill in 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee and other members of the Confederate high command watched the Battle of Fredericksburg unfold.

Howison Hill Like Lee's Hill, this hill was crowned with Confederate artillery that blasted the Union attackers in front of Marye's Heights.

Union Breakthrough Union Gen. George G. Meade's division crossed the Slaughter Pen Farm under intense artillery fire before it broke through Stonewall Jackson's line at this spot. The Confederates forced the Federals back and sealed the breach.

Prospect Hill This was the right flank of the Confederate line. Artillery here helped stop Meade's attacks. A short 2/10-mile trail leads to Hamilton's Crossing on the railroad.

Jackson Trail

Modern gravel roads follow the path taken by Stonewall Jackson's Confederates on their May 2, 1863, flank march. The park maintains the unpaved trail to give you a sense of the road Jackson followed, even though it has been widened since the battle. In 1863 some Confederates thought the trail was little better than an animal path through the woods.

Chancellorsville, April 27-May 6, 1863

Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitor Center The visitor center contains exhibits, a bookstore, and a film explaining the battle. A loop trail leads to interpretive signs and monuments to Stonewall Jackson, ending at the site where Jackson was wounded.

Bullock House Site On May 3, when Confederates captured Chancellorsville, Union Gen. Joseph Hooker pulled his men back to this location. Earthworks and artillery pits nearby mark the Union army's last line.

Chancellor House Site The building that stood here was the home of the Chancellor family. It served as an inn before the Civil War and as Hooker's headquarters during the battle. The house burned during the fighting.

McLaws' Line From here on May 1-3 Lafayette McLaws' Confederate division kept Union forces occupied while Stonewall Jackson's troops marched around Hooker's army to attack his flank.

Lee-Jackson Bivouac Here on the night of May 1, 1863, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson met to plan the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Catharine Furnace Ruins The base of the furnace stack is all that remains of this Civil War-period ironmaking facility. Jackson's troops passed here during their march around Hooker's army on May 2.

Slocum's Line Henry Slocum's Union 12th Corps held these earthworks from May 1 through mid-morning on May 3 when Confederate infantry and artillery from Hazel Grove forced the Federals to retreat to Fairview.

Jackson's Flank Attack Here at 5:15 pm on May 2, Jackson's veterans crushed the Union army's right flank held by Oliver O. Howard's Union 11th Corps.

Hazel Grove On the morning of May 3 Confederates concentrated 30 cannon here and opened a spectacular bombardment of Union artillery at Fairview.

Fairview For about five hours Union cannon here dueled with Confederate artillery at Hazel Grove while opposing infantry clashed in some of the bloodiest fighting of the war.

Old Salem Church

Baptists built this church in 1844 as a place of worship for upper Spotsylvania County. It harbored scores of refugees during the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg. Union and Confederate soldiers later fought around the church during the 1863 Chancellorsville Campaign. After the Battle of Salem Church (May 3-4, 1863), Southern surgeons treated wounded soldiers from both armies in the building.

The Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864

Grant's Headquarters As his army marched into the Wilderness, Grant made his headquarters on a slight knoll above the Orange Turnpike (Route 20). A short trail leads to the site.

Wilderness Battlefield Exhibit Shelter Exhibits provide an overview of the Battle of the Wilderness, which began here on May 5. A two-mile loop trail follows John B. Gordon's Confederate flank attack against the Union right on May 6.

Saunders Field Union attackers broke the Confederate line here on May 5, but a quick Confederate counterattack drove them out, capturing two cannon.

Higgerson Farm Some of the heaviest and most confusing fighting occurred in these fields and adjacent woods. A short trail leads to the site of the Higgerson House.

Chewning Farm The farm road to your right leads to the ridge where the Chewning house once stood. Exhibits there discuss the farm's tactical importance and its occupation by both Union and Confederate armies during the battle.

Tapp Field Here on May 6 Longstreet's corps helped rescue Lee's army from disaster. The famous "Lee to the rear" incident occurred here. A two-mile trail leads to the Widow Tapp house site, exhibits, monuments, and cannon.

Longstreet's Wounding Near here Gen. James Longstreet was wounded by the mistaken fire of his own men while making a flank attack against Union forces.

Brock Road-Plank Road Intersection This intersection was the key to the battlefield. It became the scene of heavy fighting when Grant's soldiers repulsed several determined Confederate assaults on May 5 and 6.

Ellwood

This house, owned by J. Horace Lacy, dates to the 1790s and served as a headquarters for Union Gens. Gouverneur Warren and Ambrose Burnside during the Battle of the Wilderness. Stonewall Jackson's amputated left arm is buried in the family cemetery. (Open seasonally)

Spotsylvania Court House, May 8-21, 1864

Spotsylvania Battlefield Exhibit Shelter The shelter contains exhibits about the Battle of Spotsylvania. A trail follows the opening attacks at Laurel Hill and to the spot where Union Gen. John Sedgwick was killed.

Upton's Road On May 10 Col. Emory Upton's troops used this narrow road to attack a part of the Confederate lines known as the Mule Shoe salient.

Bloody Angle On May 12 Grant captured the tip of the Mule Shoe salient. Hand-to-hand and close fighting raged around a slight bend in the trenches known as the Bloody Angle. Much of the earthworks remain.

Harrison House Site From here on May 12 Confederate Gen. John B. Gordon stopped Lee from leading a counterattack against the Federals in the Mule Shoe. Gordon then launched the attack himself. Only portions of the house foundation remain.

McCoull House Site Heavy fighting swept around this house on May 10, 12, and 18. Only the house's outline remains today.

East Face of Salient Union and Confederate troops battled over these trenches on May 12 at the same time the Bloody Angle fighting occurred. Much of the complex earthworks survive.

Heth's Salient Ambrose E. Burnside's Union 9th Corps assaulted Heth's Salient on the eastern side of the Mule Shoe. Gen. Henry Heth's Confederate defenders repulsed Burnside's attacks.

Fredericksburg Road The Fredericksburg Road became the lifeline for the Union army, allowing Grant to bring up supplies and reinforcements. Lee tried to cut it on May 19 with attacks here and at the Harris Farm (two miles north of here on Rt. 20B).

Stonewall Jackson Shrine

With his death, Stonewall Jackson transformed from a Confederate hero into an American icon.

The Stonewall Jackson Shrine is the plantation office building near Guinea Station where Gen. Thomas J. Jackson died on May 10, 1863. The office was an outbuilding on Thomas C. Chandler's 740-acre Fairfield plantation. Chandler offered his house, but Jackson's doctor chose the quiet outbuilding as the best place for Jackson to rest. Six days later Stonewall Jackson died of pneumonia.

Today, the office is the only remaining plantation structure and looks as it did when Jackson was brought here. The room in which the general died contains the original bed frame, blanket, and clock that were there that day.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park — February 14, 1927 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park (Ralph Happel, 1955)

A Study of the McCoull House and Farm, Battlefield of Spotsylvania Court House (Hubert A. Gurney, September 1939)

Applied Archaeology in Four National Parks Occasional Papers in Applied Archaeology No. 1 (June Evans, James Mueller, Doulas C. Comer, James D. Sorensen, Karen Orrence, Paula A. Zitzler and Louanna Lackey, December 1987)

Assessing tradeoffs between current and desired vegetation condition in a National Park using historical maps and high-resolution lidar data (John A. Young and Carolyn G. Mahan, extract from Restoration Ecology, Vol. 31 No. 5, July 2023)

At the Crossroads of Preservation an Development: A History of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park — Administrative History (Joan M. Zenzen, August 2011)

Cultural Landscape Report for Chancellorsville Battlefield, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park: Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation, Treatment Recommendations Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (John Auwaerter, Cathy Ponte and Nathan Powers, 2018)

Cultural Landscape Report for Chatham, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Stafford County, Virginia (Christopher M. Beagan and H. Eliot Foulds, 2019)

Cultural Landscape Report for Ellwood, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park: Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation, Treatment Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (John Auwaerter and Paul M. Harris, Jr., 2010)

Cultural Landscape Report for Wilderness Battlefield, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park: Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (John Auwaerter and James Mealey, 2021)

Foundation Document, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Virginia (November 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Virginias (January 2015)

Furnishing Plan/Historic Structures Report: Jackson Shrine (Parts a,b,c) (Ralph Happel, April 1963)

General Management Plan: Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Virginia (August 28, 1986)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2010/229 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, August 2010)

Historic Structure Report, Architectural Data Section, Chatham, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park, Virginia (Gerald Karr, January 1984)

Historic Structures Report, Part I for Jackson Shrine (1968)

Historic Structures Report, Architectural Data Section: Recommendations for the Restoration of the Jackson Shrine — Part II (Orville W. Carroll, February 1963)

Historic Structures Report - Part II, Historical Data Section: Old Salem Church, Chancellorsville Campaign, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park (Ralph Happel, August 10, 1968)

Historic Structures Report, Part I for Salem Church (1966)

Inventory of Avian Species at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Virginia NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2009/139 (September 2009)

Iron from the Wilderness: The History of Virginia's Catharine Furnace, Historic Resource Study, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park (Sean Patrick Adams, June 2011)

Jackson Trail, Chancellorsville Battlefield (T. Sutton Jett, 1940)

Junior Ranger Activity Book #2 — Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Master Plan for the Preservation and Use of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park Mission 66 Edition (A. Dillahunty and J. Cullen, 1963)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania County Battlefields (Robert Krick and Brooke Blades, April 7, 1976)

Green Springs Historic District (Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff, February 1973)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Updated May 2016 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NERO/NRR-2016/1252 (Carolyn G. Mahan and John A. Young, August 2016)

Notes on the Historic Stonewall (Sunken Road), Used as a Defence by the Confederates in the Two Battles of Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 13, 1862. and May 3, 1863 (Ralph Happel, May 1939)

Notes on the Personal Recollections of General John Gibbon (H.M. Holt and T.B. Jackson, 1939)

Preliminary Historic Resource Study: Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park (Ronald W. Johnson, October 1982)

Preliminary Report on the Second Division, II Corps Encampment Area, Stafford Heights, Fredericksburg Battlefield (October 1940)

Report on Chatham, Stafford County, Virginia (September 1963 )

Visitor Guide: The commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 2013)

Wetland Inventory and Mapping at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Virginia NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/MIDN/NRTR-2013/790 (Peter James Sharpe, Andrew Forget and Gregg Kneipp, August 2013)

Where A Hundred Thousand Fell: The Battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House: Historic Handbook #39 (HTML edition) (Joseph P. Cullen, 1966)

John Hennessy, Freedom's Tide: The Army, Emancipation, and the Fredericksburg

frsp/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025