|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1673

Selected Caves and Lava Tube Systems in and near Lava Beds National Monument, California |

OTHER CAVES IN OR NEAR THE MONUMENT

(continued)

Fern Cave

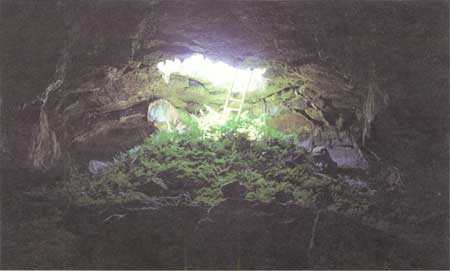

The entrance to Fern Cave (map 17, pl. 5) is 1.5 mi southeast of Hospital Rock near the northeast corner of the monument. Ferns flourish within the circle of light from a small (8 by 10 ft) entrance hole in the cave's roof. J.D. Howard named the cave and mentioned the abundance of toads as well as ferns beneath the entrance in his notes. The hole in the roof provides the only access for humans; however, a locked grate has been installed across the entrance hole to protect the ferns and some well-preserved Indian pictographs from vandalism. Visits to the cave can be arranged at the Visitor Center. Below the grate, a steel staircase in the entrance hole leads to the top of a fern-covered mound of loose blocks and soil (fig. 58). The top of this mound is flat and only about 9-10 ft in diameter, but it spreads outward to both walls of the cave. Other than this mound of rubble, and another large pile from a roof collapse upstream, most of Fern Cave is relatively free of collapse blocks or other debris.

|

| Figure 58. Fern-covered mound at entrance gives Fern Cave (see fig. 4 and map 17, pl. 5) its name. Entry is through 12-ft-diameter roof collapse. |

The cave can be traversed for 1,300 ft. At each end, further access is completely blocked by lava. At the downstream end the roof lowers until along the last 30-50 ft there is only a crawlspace between ceiling and floor. The upstream end, by contrast, is a near vertical semi-circular wall about 12 ft high. Into this underground amphitheater, lava that now forms the cave floor boiled upward from some deeper source. This molten lava almost certainly rose through a connector from an overfilled lava tube below.

Fern lava tube is large; in places the passage is more than 60 ft wide, and most of the tube is 30-40 ft wide. Ceiling heights are between 12 and 20 ft in the upstream part of the cave. Downstream from the entrance, the distance between floor and roof gradually decreases, but in most places one can stand upright until about 150 ft from the downstream end.

Fern Cave is large enough to be a downstream continuation of the Bearpaw-Skull lava tube system (fig. 4). It is likely that this major artery for the dispersal of molten lava turned east near the north end of the Schonchin Butte flow, then north near Juniper Butte, and connected with Fern Cave. However, we were unable to trace such a direct connection through the field of lava that lies south of Fern Cave.

The events of the last volcanism are recorded on the floor of Fern Cave as two recent lava flows; each can be traced the full length of the cave. The older flow is of smooth pahoehoe, which originally stood at a higher level long enough to start solidifying along its walls, but then drained down and pooled at a level 3-5 ft lower than its former stand. This process left benches 2-4 ft high with sagging edges in the downstream part of the tube where a firm crust had formed. The benches narrow and grade into a sloping apron, which connects a high-lava mark on the wall with the pahoehoe floor in the upstream third of the cave. A final flow of spiny pahoehoe occupies the central part of the cave's floor throughout its length, but it failed to overrun the aprons and downstream benches of the older flow along the walls. Thus, almost continuous gutters border the edges of this lobe in the upstream two-thirds of the cave. In most places the gutter is 2-3 ft deep; its inner wall is formed by the steep edge of the spiny pahoehoe lobe (fig. 59), and its outer wall is formed by the sloping apron or bench of the smoother older flow. The gutter is narrow in most of the upper tube but widens, and so large patches of the surface of the older flow can be seen in the downstream part of the tube. The spiny last lobe had lost most of its energy by the time it reached this downstream area; it was too viscous to spread clear to the benches, let alone cover and overwhelm them, except at the downstream end where it blocks the tube.

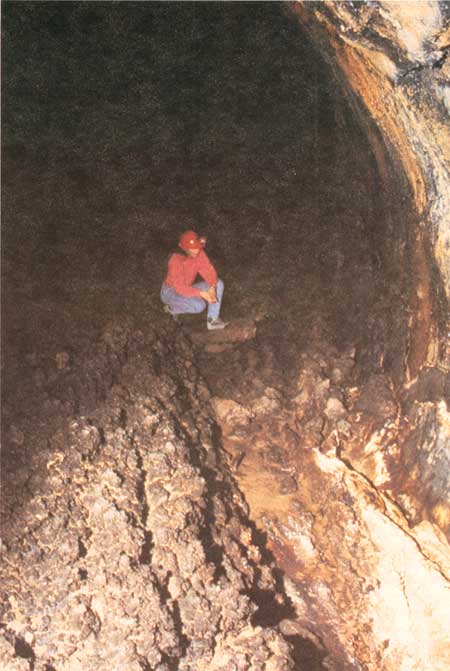

|

| Figure 59. Lava gutter formed at edge of slow-moving lava flow that last occupied Fern Cave (see fig. 4 and map 17, pl. 5). |

Downstream Through Fern Cave

In the amphitheater at the upstream end of Fern Cave is a low mound of lava that rose into the cave from an unknown source below (map 17, pl. 5). During the final stages of this upwelling, a few blocks fell from the roof and stuck in the pasty half-molten lava on the surface of this mound. Other, mostly larger collapse blocks within the same area tumbled onto the surface after the lava had congealed.

The relatively smooth mound of upwelled lava becomes spiny pahoehoe downstream. As previously mentioned, the final lava lobe does not cover the entire floor of the cave: its edges form the inside walls of the lava gutters that developed along each wall of the cave. The edge of the older flow is seen as a sloping apron that forms the outer wall of the lava gutters. Patches of this apron also can be seen on the walls of the amphitheater at a level slightly higher than the top of the upwelled mound.

The tube makes a sharp right-angle bend to the left (northwest) 125 ft downstream. The gutters continue on, but the one on the northeast side is partly overridden by young spiny pahoehoe where this flow rounded the outside of the bend. At small alcoves along the wall, the more recent spiny pahoehoe cuts across the alcove to reveal wide areas of the older pahoehoe beneath.

Throughout this upstream several hundred feet of passage are patches of tan silt. The silt has slowly filtered down cracks in the cave's roof and formed four irregular layered deposits. Amorphous silica has cemented the upper surfaces of the silt as well as lining the small drip pits—called conulites—in these silt patches.

Lavacicles occur on the roof of Fern Cave except where roof collapse has removed them. A few faint high-lava marks are present on the walls; however, peeling edges of lava plaster are much more common than high-lava marks as records of recurrent fluctuation of lava level within the tube prior to development of the two final flows. The walls have a flowing drapery of generally unbroken dripstone plastered over most areas. Nearly 175 ft farther down the tube is an area of small lava stalagmites built up of lava droplets from the ceiling. Downstream 140 ft farther is a lone rafted block nearly buried at the edge of the down-peeled east balcony.

Approximately 525 ft downstream from the right-angle bend, a huge pile of large collapse blocks fell from the roof, and for 150 ft they restrict access through the tube. The easiest and safest bypass is along the east wall.

The upstream edge of the collapse breccia is a reference point for finding two interesting minor features. On the west wall, 20-30 ft upstream from the edge of the collapse pile, and just where the wall turns right (north) downstream, a patch of hollow dripstone tubelets emerges from a crack in the wall 5 ft above the floor. Near a point 100 ft upstream from the big collapse pile in the middle and eastern section of the tube are lava stalagmites built up 4-8 in. above the spiny pahoehoe floor. They are few in number but increase upstream over a distance of 100 ft.

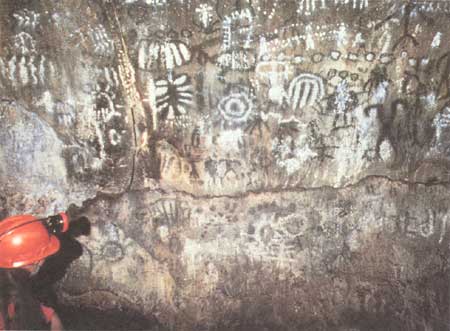

Downstream from the big collapse pile the next feature to note is the mound of blocks, pumice, and soil beneath the hole in the roof. The abundant ferns, lichens, mosses, and other plants release water vapor and oxygen to the air. The feel and smell is somewhat like that in a greenhouse. Within the area where a circle of light from the entrance illuminates the cave are the most abundant records of early human habitation. The finest display of pictographs within the monument is on the walls of the cave (fig. 60) upstream from the entrance. Some are faint and possibly quite old; others appear very clear and fresh. Archaeologists have enhanced large areas with a white overlay. Grinding holes for preparing food pit the surface of several roof blocks strewn around the edge of the fern-covered mound.

|

| Figure 60. Indian pictographs on wall of Fern Cave (see fig. 4) near entrance are among the best-preserved in Lava Beds National Monument. |

Downstream, the most notable geologic feature is the absence of the sloping apron on the outside wall of the gutters and its replacement by a lava bench. Some wider parts of this lava bench record an earlier history. Here peelings of thin lava plaster contributed more to the volume of the bench than solidification at the high-lava line of the next-to-last flow that occupied the cave. Some areas of the early lava floor as much as 110 ft long and 20 ft wide were not covered by the late lobe of spiny pahoehoe.

The ceiling height lowers to 6 ft or less in the area within 250 ft from the downstream end of the tube, and it is much easier to examine the distribution of lavacicles in detail on this lowered ceiling. Near the west wall of the tube, 120-200 ft upstream from the tube's end (where the tube makes a slight bend to the left—northwest—as you look downstream), the lavacicles are oriented along parallel ribs in the ceiling. The lavacicles on these ribs are wide triangular blades resembling large shark teeth more than icicles. Near the center of the tube are thin, spindly lavacicles; some are curved at their tips as if buffeted by gusts of hot gases while they were forming.

The downstream end of the tube shows very clearly how the last two lava flows gradually filled in this large tube until the spiny lobe met the ceiling. Two small extensions remained open with a 6-in. clearance on either side of the central area where the lava first touched the roof, but each of these is closed tight in another 5-10 ft. It is unusual that lava did not pile up in a block jam behind this constriction. The lava did swell up, raising its central part, but we observed no marked fracturing of a congealed surface as would be created by lava pushing up from beneath.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1673/sec3i.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006