|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

GUIDEBOOK OF THE WESTERN UNITED STATES.

PART A. THE NORTHERN PACIFIC ROUTE, WITH A SIDE TRIP TO YELLOWSTONE PARK.

By MARIUS R. CAMPBELL and others.

INTRODUCTION

If his journey to the Pacific coast begins at one of the great cities on the Atlantic seaboard, the traveler, when he reaches St. Paul, the eastern terminus of the Northern Pacific Railway, will have gone nearly halfway across North America. He will have traversed or perhaps gone around the Appalachian Mountain region and then crossed the prairie States, which, in wealth and population, form in themselves an empire.

St. Paul is in the prairie region, but the boundary between the prairies and the Great Plains is vague and undefined, and the traveler will at no place perceive the change from prairie to plain or from the East to the West. On leaving St. Paul he first passes across rolling prairies, interspersed with forests of pine and hardwood trees, and within a short distance these prairies give place to the vast treeless plains which, stretching a thousand miles west of the Mississippi, rise almost imperceptibly to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The annual rainfall diminishes in the same direction from 28 inches at St. Paul to only half that amount in central Montana, and the traveler, as he goes Westward, will note more and more of the features that he has habitually associated with the West. Prairie dogs and jack rabbits are seen; one by one the flowers and shrubs of the Mississippi Valley disappear and are replaced by those of a semiarid country; trees grow only on the moist bottom lands along the streams; intensive cultivation is possible only in the valleys, though the uplands are being brought into use by dry farming and are yielding fair crops of the more hardy grains.

Throughout much of the region traversed the face of the country has been greatly modified by the vast ice sheets of the glacial period which covered the northern part of the continent and left immense deposits of loose material on the surface of hard rock in the northern part of the United States. The history and the phenomena of this glaciation are considered in detail at several places in this book.

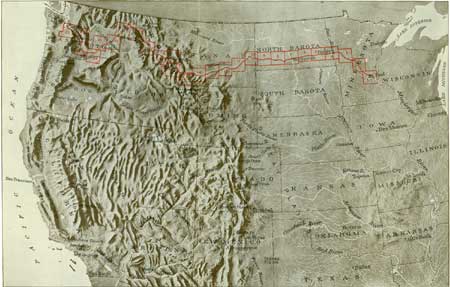

The general features of the country west of the Mississippi are represented on Plate I. When, after crossing the Great Plains, the traveler reaches the foothills of the Rocky Mountains he will have attained a height of 4,000 feet above the sea, a height reached by few peaks in the Eastern States outside of the Adirondacks and the White Mountains. The Rocky Mountains form a great, irregular, rough-hewn "backbone" for the continent. They comprise many groups of ranges, in which some peaks in Montana and Idaho reach a height of 12,000 feet above sea level and some in Colorado rise more than 14,000 feet.

The western mountains, like the eastern, are the worn remnants of upward folds or crumples or of upheaved blocks of the fractured earth crust, but, unlike the eastern mountains, which are geologically old, the western mountains are geologically very young. They are therefore higher, for since they were uplifted there has not been time for ice, rain, heat, frost, and wind to wear them down to lower levels.

West of the Rocky Mountains lies a broad interior basin, in the northern part of which, with its inclosing mountains, there is sufficient rain and snow to maintain the flow of the great Columbia River; but in the southern part, in what is known as the Great Basin, the mountain streams find no outlets to the sea, their waters, so precious for irrigation, being soon lost in the thirsty lowlands, and the feeble or intermittent rivers of the valleys carry their waters down to be evaporated in alkali marshes or on saline deserts.

The part of the Columbia River basin or plateau that is traversed by the Northern Pacific Railway is made up of lava flows, among the greatest in the world, which in comparatively recent geologic time spread like a fiery flood over hundreds of thousands of square miles; and a wide expanse of hard, dark volcanic rocks, whose surface is here and there cut deeply by streams, shows the enormous extent and volume of these eruptions. The part of this old lava plain that is crossed by Columbia River is the most arid region traversed by this route. The precipitation in this region is sometimes not more than 6 inches annually, but despite the small rainfall the uplands have become the great wheat-raising country of the Northwest.

The last great natural feature to be crossed by the traveler is the Cascade Range, which separates the interior basin from the region of Puget Sound. This range is a broad upland that stands from 6,000 to 8,000 feet above the sea, and here the evidences of volcanic activity continue to be conspicuous. On the flanks of the range rise the snow-covered peaks of Mount Rainier, Mount Adams, and other cones, which were once active volcanoes, pouring forth streams of lava and showers of rock fragments. Of these great conical masses, built up by successive lava flows and by the accumulation of rock fragments blown from the craters, the highest is Mount Rainier, towering 14,408 feet above Puget Sound, from which it presents a magnificent spectacle, its upper slopes covered by great streams of moving ice, the largest glaciers in the United States south of Alaska.

On emerging from the Cascades the traveler enters a broad lowland, which is separated from the Pacific Ocean by the Olympic Mountains, but which contains Puget Sound with its many branching waterways, one of the most remarkable bodies of salt water on the globe.

NOTE.—For the convenience of the traveler the sheets of the route map in this bulletin are so arranged that he can unfold them, one by one and keep each one in view while he is leading the text relating to it. A reference is made in the text to each sheet at the place where it should be so unfolded, and the areas covered by the sheets are shown on Plate I. A list of these sheets and of other illustrations, showing where each one is placed in the book, is given on pages 205-207. A glossary of geologic terms is given on pages 199-203 and an index of stations on pages 209-212.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/intro.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006