|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

ITINERARY

|

|

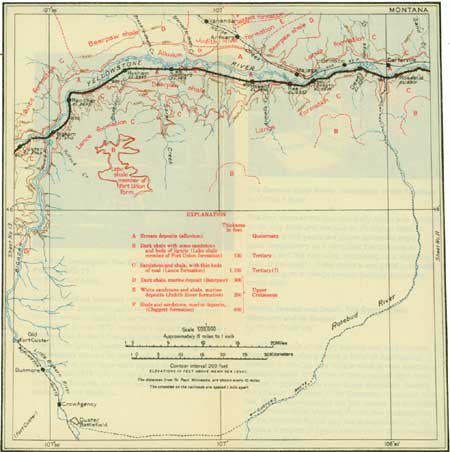

SHEET No. 12. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Rosebud. Elevation 2,501 feet. Population 370.* St. Paul 778 miles. |

West of Fort Keogh the railway follows the river past the small villages of Hathaway and Joppa to Rosebud, at the mouth of Rosebud River. (See sheet 12, p. 78.) The scenery along this part of Yellowstone River is not particularly striking, but many interesting views may be obtained, especially if the trip is made late in the season, when the water is low, for at that time it is generally clear, whereas in June the stream, swollen by the melting snow in the mountains, becomes a muddy torrent. Streams in this condition may be interesting as vehicles for the transportation of earthy material, but they are certainly not attractive.

Where the river swings close against the rocky bluffs the traveler may obtain through the soft foliage of the willows and cottonwoods vistas of deep, quiet pools that reflect all the colors of the clouds and sky, or of tumbling rapids where accumulated bowlders interfere with the progress of the stream. These views have for a setting on one side bold and rugged cliffs and on the other the upland stretching away to the horizon in a monotonous expanse of dry and dusty plain. In other places the outlook is over the wide valley bottom, which irrigation has made an oasis in the desert of sagebrush hills and broken cliffs.

The Lance formation makes rugged bluffs along the river from Miles City to Forsyth. This formation extends across North Dakota, Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming. The coal or lignite beds that characterize it in many places and the fossil leaves and branches that have been found almost everywhere in the sandstone and shale composing it show clearly that it was laid down in lakes and ponds. It is also certain that at the time it was deposited great forests flourished over much of the area of the States mentioned, where are now the treeless wastes of the Great Plains. The trees of that time were similar to those of the Fort Union epoch, as described on page 57. The formation of coal beds means that the land was flat and probably at low level. The plains country and much of that which is now mountainous was at that time low and swampy, supporting a luxuriant tangle of large trees, underbrush, vines, and water plants. The strange creatures that roamed through that ancient forest or swam in its shallow lakes are described below by Charles W. Gilmore, of the United States National Museum.1

1Where vegetation grew as luxuriantly as in the swamps and lowlands of Lance time there must have been animals to subsist upon it and in turn other animals to feed upon them. The Lance formation is noted for the remains of great reptiles that it contains, and all the large museums of the country have skeletons or models of these wonderful dinosaurs, as they are called.

One of the best-known dinosaurs is called Triceratops (meaning literally three-horned face), so named because he had over each eye a massive horn directed forward and terminating in a long, sharp point and a third, but much smaller horn, on the nose, not unlike that of the modern rhinoceros. A mounted skeleton of Triceratops in the National Museum in Washington is about 20 feet long and stands 8 feet high at the hips. Some of the skulls that have been found measure more than 8 feet, or nearly one-third of the length of the entire animal, including the tail. The great length of skull is due to the fact that the neck was protected by a bony frill, which projected backward from the skull like a fireman's helmet or like the large ruffs that were worn in Queen Elizabeth's time. Although the brain of this dinosaur is large, it is, when the size of the skull is taken into consideration, relatively smaller than that of any other known land animal.

That Triceratops was a fighter is shown by the finding of broken and healed bones. A pair of horns in the National Museum bear mute witness to such an encounter, for they had been broken and then rounded over and healed while the animal was alive.

In the earlier restorations or models of this animal, as shown in Plate X (p. 74), the skin was represented as being smooth and leathery, but in a specimen recently discovered the well-preserved skin shows that it was made up of a series of scales of various sizes.

Triceratops, as indicated by the structure of his teeth, was manifestly a plant-eating animal, his food probably being leaves and branches of low trees and shrubs. Hatcher, the most noted collector of Triceratops in the United States, has pictured the country at the time these animals lived as being made up of vast swamps with wide watercourses that were constantly shifting their channels, the whole resembling the Everglades of Florida. The entire region, where the waters were not too deep, was covered by an abundant vegetation and inhabited by the huge dinosaurs as well as by crocodiles, alligators, turtles, and diminutive animals, fossil remains of which are now found embedded in the sand and mud that were deposited in those old swamps.

There lived at the same time the great duck-billed reptile Trachodon, the best-known and presumably the commonest dinosaur of its time. The length of an average-sized individual, measured from the end of the nose to the tip of the tail, was 30 feet, and as he walked erect on his huge three-toed hind feet, the tip of the head, which was nearly a yard long, was from 12 to 15 feet above the ground. The nose expanded into a broad duck-billed beak, which was covered with a horny sheath, as in birds and turtles, and was admirably adapted to pulling up the rushes and other water plants upon which the creature lived. That Trachodon lived in the water is shown by the webbed fingers of the fore foot and the long, deep, flattened tail, which was a most efficient swimming organ and equally useful as a counterbalance to the weight of his body when he was striding about on his hind legs on the land. The skin, as shown by specimens that have been found, was thin and covered with tubercles of two sizes the larger ones predominating on surfaces exposed to the sun. One of the most remarkable features of this great brute was the set of teeth with which he was provided. In that respect he was much better off than the human being, for as soon as a tooth was worn out or lost, it was replaced by another pushed up from below. Each jaw had from 40 to 60 rows on each side and from 10 to 14 teeth in each row, hence there must have been more than 2,000 teeth in the mouth of one individual.

There were also flesh-eating and consequently armored reptiles in Lance time. The most highly specialized of the armored reptiles was Ankylosaurus, which was covered by a great number of flattened ridged-skin plates of bone, arranged in rows across the broad back. The reptile was low of stature and had at the end of his stout, heavy tail a great triangular club of bone, which when he moved about must have dragged on the ground. The head was short and blunt, and the eye was provided with a cup-shaped bony shutter that could be closed over the eyeball when the creature was harassed by his enemies. With all vulnerable parts thus protected by bony armor, this living fortress had little to fear from his blood thirsty contemporaries. Ankylosaurus doubtless had need of his armor, for there were many other flesh-eating dinosaurs that swarmed in the forests or swam in the sluggish waters. The most striking of these was Tyrannosaurus, or tyrant lizard, the largest land-walking carnivorous animal the world has ever known. He was 40 feet long and, in a standing position on his hind legs, was 18 or 20 feet high. The fore legs were exceedingly small, and he must have walked entirely upon his powerful hind legs, the knee joint of which was 6 feet above the ground. At the American Museum of Natural History, New York, there is a perfect skull of this animal. It is with a feeling of awe that the spectator stands before the huge head with jaws 4 feet long, filled with bristling rows of sharp-pointed teeth, several of which project at least 6 inches from their socket, and he can not help wondering what part such a creature played in the economy of nature and whether he was as important to his time and place as the animals that live to-day.

During Lance time the crossing of the continent must have been attended by dangers beside which those of the African wilds seem trivial indeed. The traveler may be glad that he is safely ensconced in a railway car instead of facing the terrible ferocity of some wandering dinosaur as big as a house. But the days of these monsters have passed away, and their former presence is recorded only in the skeletons which here and there are found embedded in the rocks. Just across the river from Forsyth a skeleton of Triceratops was found several years ago, and bones of these animals may be seen occasionally in riding about the country.

|

| PLATE X.—THE GREAT TRICERATOPS (THREE-HORNED FACE), WHICH IN LANCE TIME ROAMED THROUGH THE FORESTS OF MONTANA AND NORTH DAKOTA. From painting by C. R. Knight, made under the direction of J. B. Hatcher. |

|

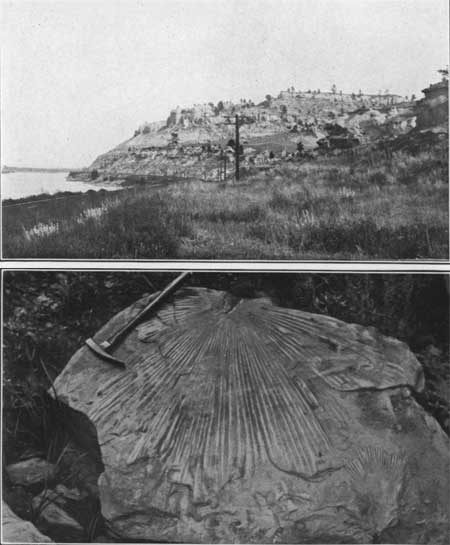

| PLATE XI.—A (top), BLUFFS OF LANCE FORMATION ON YELLOWSTONE RIVER WEST OF HYSHAM, MONT. B (bottom), FOSSIL PALM LEAF OF EOCENE AGE FOUND NEAR HYSHAM, MONT. The climate of Montana, must have been warmer and more moist than it is to-day to have permitted the growth of palms and other subtropical plants. |

|

Forsyth. Elevation 2,535 feet. Population 1,398. St. Paul 791 miles. |

Forsyth, the county seat of Rosebud County, a district terminal of the Northern Pacific Railway, is one of the thriving towns in the Yellowstone Valley. It was named for Gen. J. W. Forsyth, one of the military pioneers of this country. Opposite the town the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, which has followed Yellowstone River from Terry, leaves the valley and goes in a northwesterly direction to the Musselshell Valley in the vicinity of the new towns of Musselshell and Roundup.

Beyond Forsyth an anticline crosses the Yellowstone Valley, but it is not so distinct as the one above Glendive. The first indication that the traveler may observe of a change from the Lance formation, which is at railway level from Terry to Forsyth, is that after passing Armells Creek, just beyond milepost 130, the width of the valley suddenly increases and the bluffs lose their rugged character. These features indicate the presence of softer rocks, and while the formation containing them is not visible from the train a close examination of the bluffs would show that they are composed of dark shale—the same dark shale that the traveler saw at Cedar Creek, above Glendive. This shale normally underlies the Lance, and its presence near railway level here means that the rocks rise west of Forsyth and the next lower formation is brought to view.1

1The dark shale noted near Glendive is called the Pierre shale, but the dark shale that makes its appearance near Howard and is said to be the same as the Pierre, is called Bearpaw. The change in the Cretaceous formations along an east-west line from the Black Hills to Billings, Mont., and the reason for the introduction of new names for the formations are explained by figure 9, which is supposed to represent the cut edges of the formations as they lie in the ground.

FIGURE 9.—Diagram showing the thinning out and coming in of formations from the Black Hills, S. Dak., to Billings, Mont. In the Black Hills, and so far as known at Glendive, the Upper Cretaceous rocks begin with the Dakota sandstone at the base, resting upon the Lower Cretaceous. Over this are two great shales (Benton and Pierre) and a limestone (Niobrara) of marine origin, and capping all is the Lance, a fresh-water deposit.

Westward from the Black Hills the Niobrara fades out as a limestone, and at Billings it can not be identified and separated from the Benton. The entire mass of shale is called the Colorado, and this is equivalent to both the Benton and the Niobrara. The Dakota disappears west of the Black Hills and the Colorado shale rests upon the Kootenai (Lower Cretaceous).

In the east the great marine deposit above the Niobrara is known as the Pierre shale. Toward the west this changes in character in its lower part, and three more or less sandy formations—the Eagle sandstone and the Claggett and Judith River formations—have been recognized and named. The dark shale above the Judith River is in composition and appearance like the Pierre, but as it represents only a small part of that formation it is given another name (Bearpaw). The Lance formation is apparently continuous and regular throughout the section here described.

|

Howard. Elevation 2,600 feet. Population 139.* St. Paul 800 miles. Finch. Elevation 2,595 feet. St. Paul 806 miles. |

The high hills composed of Lance sandstones (see Pl. XI, A, p. 75), as shown on sheet 12 (p. 78), recede from the river until at Howard they are more than 2 miles from the railway, and the low hills near by are made up of the Bearpaw shale. The outcrop of the shale crosses the river and then swings far to the northeast around a dome-shaped structure in the rocks that brings this and lower formations up to the surface.

The valley increases in width until in the vicinity of Finch the Lance sandstones are so far back from the river that they are hidden by the low hills of shale at the margin of the valley bottom. At milepost 141, a short distance east of Sanders, a massive gray sandstone rises from river level until it attains a height above the railway of about 30 feet. Beyond this point it descends toward the west and within a short distance disappears below railway level. The highest point on this sandstone marks the axis of a large irregular uplift which lies almost entirely north of the railway.

This sandstone is known to be the extreme eastern point of the Judith River, a coal-bearing formation (see fig. 9) that is exposed in many places in the central part of the State. In its best development it is a fresh-water deposit, but the sandstone near Sanders contains marine shells, showing that the shore of the land upon which the fresh-water sediments of the central part of the State were laid down was near this place, and that to the east of that shore line sand was deposited in the waters of the sea. A deep well recently drilled for water at Vananda, on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway about 16 miles northwest of Forsyth, started in this sandstone and struck the red shale of the Kootenai formation (see fig. 9) at a depth of about 3,200 feet.

The relatively flat land in the bottom of this valley, although originally only a sagebrush plain, was attractive to farmers, and an extensive private irrigation project has been developed. Water is taken from the river at Myers, between Hysham and Rancher, and carried by a gravity system down the valley for a distance of 30 miles. Part of this system has only recently been opened, so that all the land is not cultivated, but in the older parts fine crops are raised.

|

| PLATE XII.—A (top), B (bottom), VIEWS IN THE SHEEP RANGE OF MONTANA. As shown in the upper view, the watchful herder and the equally vigilant sheep dogs guard the defenseless flock. The covered wagon shown in the lower view has been developed to meet the special needs of the sheep herder. It is light in weight and commodious and in bad weather affords protection from the fierce storms which sweep over the Montana plains. |

|

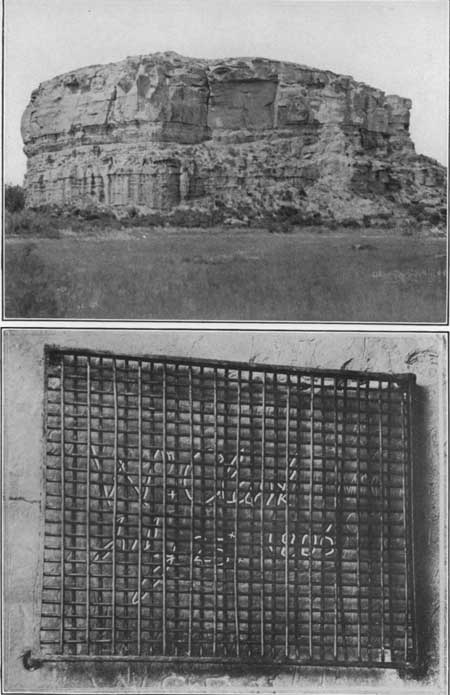

| PLATE XIII.—A (top), POMPEYS PILLAR, MONT., AS SEEN FROM THE NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILWAY. The inscription shown below is one the other side of the pillar. B (bottom), INSCRIPTION MADE BY CAPTAIN CLARK ON POMPEYS PILLAR JULY 25, 1806. Now protected by an iron grating. Photograph furnished by the Northern Pacific Railway. |

|

Sanders. Elevation 2,618 feet. Population 281.* St. Paul 812 miles. Hysham. Elevation 2,607 feet. Population 162.* St. Paul 818 miles. |

West of the sandstone outcrop the valley floor is again smooth, showing that the soft shale forms it as well as the low hills that appear far to the left (south). A little beyond Sanders the railway crosses Sarpy Creek, one of the well-known places of the early days, for here was located Fort Sarpy, an important trading post of the American Fur Co. and the headquarters of many of the hunters and trappers of the Northwest. The post was named for if not established by Col. Peter Sarpy, who was an agent of the fur company for 30 years after its organization.

At Hysham the valley is very wide, the hills being at least 2 miles back from the railway. By looking ahead on the left, after leaving this town, the traveler can see the rugged sandstone walls of the Lance formation coming in close to the track, and for several miles the road follows the river bank under a towering cliff that rises to a height of 300 feet.

|

| FIGURE 10.—Monument built by sheep herder. |

The traveler is now in what was a few years ago the great open sheep range of Montana. Single ranches had flocks ranging from a few hundred to as many as 40,000 sheep. These were not kept in a fenced inclosure as is done in the East but were herded in bands of a few hundred or a few thousand each. To each band was assigned one or two herders who with horses to draw a covered wagon and a faithful dog followed the sheep for months at a time without returning to the home ranch. (See Pl. XII.) Hour after hour, day after day, and week after week were spent in watching the sheep, with absolutely nothing to break the monotony of the rolling treeless plain except here and there low hills of barren rock. The herder would stand upon such eminences when the sheep were quietly feeding and no coyotes near to cause uneasiness and, to amuse himself, would build monuments of the loose rocks (fig. 10). In the course of time monuments of this kind were erected on almost every hill and on all the commanding points of the river bluffs, and the traveler can doubtless see them from the passing train.

The dry-land farmer has gradually encroached upon the open range, and before long large flocks feeding upon it will be seen no more. Conditions will become more and more like those in the East, and finally the sheep herder, like his enemy the cowboy, will pass out of existence and will live only on the canvas of some Remington or Russell.

|

Bighorn. Elevation 2,712 feet. St. Paul 834 miles. |

The next station is Bighorn, which is only a short distance east of Bighorn River. This is historic ground also, for it has been occupied almost continuously since it was first visited by Capt. Clark July 26, 1806. In the year immediately following Clark's visit Manuel Lisa, one of the restless, adventurous spirits of the frontier, established trading post here which afforded a rendezvous for many of the hunters of the region. In 1822 Col. William H. Ashley, president of the Rocky Mountain Fur Co., built a trading post 2 miles below the mouth of Bighorn River which he called Fort Van Buren. It was here also that Gen. Gibbon, in 1876, crossed the Yellowstone and proceeded overland with his detachment of 450 men to cooperate in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which Custer had already lost.

|

Custer. Elevation 2,749 feet. Population 335* St. Paul 839 miles. |

A little beyond Bighorn station the train crosses Bighorn River and, skirting the base of sandstone bluffs for a distance of 3 miles, plunges into the blackness of the Bighorn tunnel, to emerge at the town of Custer. This town derived, its name from the fact that it was the stopping place for persons going to old Fort Custer, at the mouth of Little Bighorn River, but, despite the fact that the post has been abandoned, Custer retains its importance on account of its situation in the center of a fine agricultural district. Several years ago the skeleton of a Triceratops was found in the Lance formation which makes the river bluff opposite this place.

West of Custer the bluffs on both sides of the river are composed of sandstone of the Lance formation, but they are not so prominent as those below the mouth of Bighorn River. In places the low hills rise abruptly from the water's edge and the roadbed of the railway was made by blasting the solid rock. Generally, however, the hills are back half a mile or so from the track.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/sec13.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006