|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

COUNCIL BLUFFS, IOWA, TO OGDEN, UTAH.

|

Council Bluffs, Iowa. Elevation 980 feet. Population 29,292. |

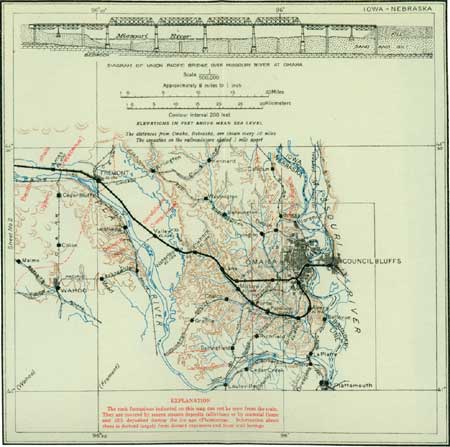

Abraham Lincoln established the eastern terminus1 of the Union Pacific Railroad on the east side of Missouri River, so that the Overland Route begins at Council Bluffs, Iowa (see sheet 1, p. 18), although the offices, shops, and general terminal facilities of the road are west of the river, at Omaha. Council Bluffs is on the broad flood plain of Missouri River, at the foot of high bluffs composed mainly of a claylike material known as loess. According to tradition these bluffs were used for centuries by the Indians as a common meeting ground; here the several tribes held their pow-wows, smoked their pipes of peace, or declared hostilities, as their inclinations moved them. The name Council Bluffs was originally applied to a locality about 20 miles north of Omaha, where Lewis and Clark held council with the Indians. Later it was transferred to the site of the present city.

1President Lincoln's Executive order of November 17, 1863, and a supplemental order of March 7, 1864, were issued under the law of July 1, 1862, which created the Union Pacific Railroad Co. and which authorized the President of the United States to establish its eastern terminus on the western boundary of Iowa. This required the company to provide for the difficult crossing of Missouri River.

The passage of this law authorizing the building of a road to the Pacific coast was preceded by a long debate. The northwestern region acquired by the Louisiana purchase of 1803 had been explored by Lewis and Clark, whose expedition started in 1804. Their report aroused great interest and stimulated many military, trading, and exploring expeditions, but there was great opposition to the holding of the "western wilderness" in the Union. This was voiced in 1825 by Senator Dickerson, of New Jersey, who said, in debate: "But is this Territory of Oregon ever to become a State, a member of this Union? Never. * * * The distance * * * that a Member of Congress of this State of Oregon would be obliged to travel in coming to the seat of government and returning home would be 9,300 miles. * * * If he should travel at the rate of 30 miles per day, it would require 306 days. Allow for Sundays, 44, it would amount to 350 days. This would allow the Member a fortnight to rest himself at Washington before he should commence his journey home. This traveling would be hard, as a greater part of the way is exceedingly bad, and a portion of it over rugged mountains where Lewis and Clark found several feet of snow in the latter part of June. Yet a young, able-bodied Senator might travel from Oregon to Washington and back once a year; but he could do nothing else. It would be more expeditious, however, to come by water round Cape Horn, or to pass through Bering Strait, round the north coast of this continent to Baffin Bay, thence through Davis Strait to the Atlantic, and so on to Washington. It is true, this passage is not yet discovered, except upon our maps, but it will be as soon as Oregon shall be a State."

But when California was acquired by the United States, and especially after the discovery of gold, the Pacific coast became of great importance to the citizens of the East, and routes leading to it were carried across what had been a trackless wilderness. The western migration which received its greatest impetus in the gold rush of 1849, developed some famous trails, one of which, the "Overland Trail," was the forerunner of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads. The convincing arguments in favor of its construction seem to have been military and political rather than commercial. President Lincoln advocated it not only as a military necessity but also as a means of keeping the Pacific coast in the Union. The name Union Pacific probably resulted from the belief that the road would bind the Union together.

|

|

SHEET No. 1. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

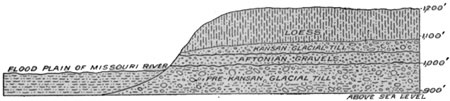

The loess1 north of Council Bluffs lies above loose sand and gravel known as the Aftonian gravels (fig. 1). The outcrop of these gravels is marked by a line of springs, for the underground water passes through them more readily than it passes through the less porous material above and below. From these gravels in some parts of Iowa have been collected the bones of mastodons, camels, and many other animals no longer found in North America.2 (See Pl. II, p. 10.)

1Loess is a peculiar silt, claylike loam, or fine-grained sand, which strongly resists weathering. The name is supposed to be derived from the German word losen (to loosen), because of the tendency of the material to split off in vertical columns. In color loess is generally buff or yellowish brown. It covers large areas in North America, where its beds were probably formed after the ice of the glacial period had disappeared. Its mode of origin is not certainly known. Some beds of it consist of material lifted by the wind from the valleys where it had been deposited by streams. Others probably were deposited in water along stream courses or in temporary lakes. In places it contains bones and teeth of animals and shells of snails. If properly watered it makes good soil.

2The animals of the Pleistocene (plice'-toe-seen) epoch (see table on p. 2) are interesting because they are nearer to us in time than others of the past and therefore most nearly like some animals now living; yet those that lived in North America during this epoch were very different from those living here to-day. To find the descendants or near relatives of the Pleistocene animals of North America we must go to other continents, for some of them as far away as India. The North American animals were doubtless scattered by the changes in climate that resulted in the advances and retreats of the continental ice sheet during the Great Ice Age.

The fauna, or assemblage of animals, of early Pleistocene time was varied in character. The animals were adapted to the mild climate that then prevailed and remained until after the southward advance of the ice sheet, but were driven away or exterminated before the close of the ice age, and their place was taken by animals such as are now found only in the frozen areas of the North. When the ice melted away and a climate as mild as that of the present day was established, these arctic species followed the retreating ice front northward, and their place was taken by animals adapted to life in a temperate climate.

One of the effects of the climatic changes and the resulting migration of animals was a radical change of fauna. Could one of the Pleistocene men return and view the present-day animals they would seem as strange to him as those of an African jungle are to an inhabitant of the Great Plains. Prof. W. B. Scott, in his history of land mammals, says of the Pleistocene fauna:

"It is probable that the Pleistocene fossils already obtained give us a fairly adequate conception of the larger and more conspicuous mammals of the time but no doubt represent very incompletely the small and fragile forms. With all its gaps, however, the record is very impressive. * * * The fossils have been gathered over a very large area, extending from ocean to ocean and from Alaska to Central America. Thus their wide geographical range represents nearly all parts of the continent and gives us information concerning the mammals of the forests as well as of the plains.

"Those divisions of the early and middle Pleistocene which enjoyed milder climatic conditions had an assemblage of mammals, which from one point of view seems very modern, for most of the genera and even many of the species which now inhabit North America date back to that time. From the geographical standpoint, however, this is a very strange fauna, for it contains so many animals now utterly foreign to North America, to find near relatives of which we should have to go to Asia or South America. Some of these animals which now seem so exotic, such as the llamas, camels, and horses, were yet truly indigenous and were derived from a long line of ancestors which dwelt in this continent but are now scattered abroad and are extinct in their original home, while others were migrants that for some unknown reason failed to maintain themselves. Others again are everywhere extinct.

"Most surprising, perhaps, in a North American landscape is the presence of the Proboscidea, of which two very distinct kinds, the mastodons and the true elephants, are found together. Over nearly the whole of the United States and southern Canada, and even with sporadic occurrence in Alaska, ranged the American mastodon (Mastodon americanus), which was rare in the plains but very abundant in the forested regions, where it persisted till a very late period and was probably known to the early Indians. This animal, while nearly related to the true elephants, was yet quite different from them in appearance. * * * The tusks were elephant-like, except that in the male there was a single small tusk in the lower jaw, which can not have been visible externally; this is a remnant of an earlier stage of development, when there were two large tusks in the lower as well as the upper jaw. The creature was covered with long, coarse dun-colored hair; such hair has been found with some of the skeletons.

"Of true elephants, the North American Pleistocene had three species. Most interesting of these is the northern or Siberian mammoth (Elephas primigenius), a late immigrant from northern Asia, which came in by way of Alaska, where Bering Land (as we may call the raised bed of Bering Sea) connected it with Asia. The mammoth was abundant in Alaska, British Columbia, and all across the northern United States to the Atlantic coast. Hardly any fossil mammal is so well known as this, for the carcasses entombed in the frozen gravels of northern Siberia have preserved every detail of structure. It is thus definitely known that the mammoth was well adapted to a cold climate and was covered with a dense coat of wool beneath an outer coating of long, coarse hair, while the contents of the stomach and the partly masticated food found in the mouth showed that the animal fed upon the same vegetation that occurs in northern Siberia to-day. * * * This is the smallest of the three Pleistocene species—9 feet [high] at the shoulder. The mammoth was not peculiar to Siberia and North America, but extended also into Europe, where it was familiar to paleolithic man, as is attested by the spirited and lifelike carvings and cave paintings of that date. Thus, during some part of the Pleistocene, this species ranged around the entire northern hemisphere."

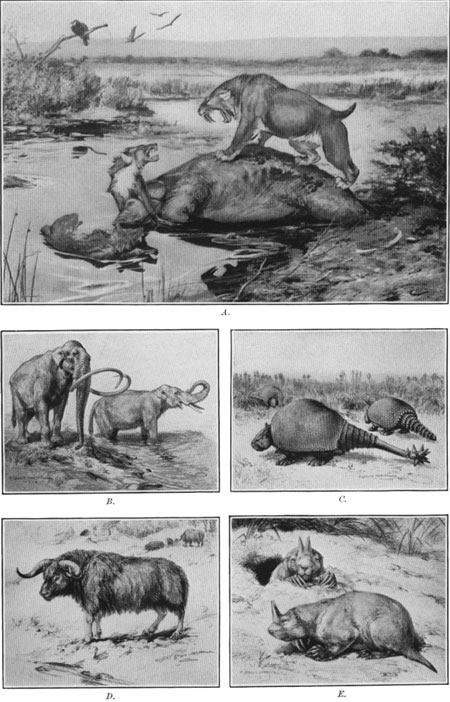

Two notable contemporaries of the mammoth were the Columbian elephant, Elephas columbi [Pl.II, B], which attained a height of about 11 feet, the size of the largest African elephants, and the imperial elephant, Elephas imperator, the largest of the American forms, which attained a height of 13 feet 6 inches.

PLATE II.—ANIMALS THAT LIVED IN CENTRAL NORTH AMERICA DURING PLIOCENE AND PLEISTOCENE TIME. A, Saber-toothed tiger and giant wolves on the carcass of a Pleistocene elephant; B, Pleistocene elephants (Elephas columbi), much larger than the modern elephants; C, Glyptodonts, Pleistocene armadillo-like animals (South American forms); D, Pleistocene musk ox, an animal as big as a small cow; E, Pliocene horned gophers, animals about the size of woodchucks. After Scott. Published by permission of The Macmillan Co. "This great creature [the imperial elephant] was characterized not only by its enormous stature but also by the proportionately very large size of its grinding teeth and was a survivor from the preceding Pliocene epoch; it is not known to have passed beyond the middle Pleistocene and was thus the first of the species to become extinct. In geographical range the imperial elephant was a western form, extending from the Pacific coast almost to the Mississippi River, east of which it has never been found, and from Nebraska southward to the City of Mexico. The meaning of this distribution is probably that this elephant shunned the forests and was especially adapted to a life on the open plains. * * *

"Many hoofed animals, far more than now inhabit North America, are found in this Pleistocene fauna. The Perissodactyla were represented by horses and tapirs, but not by rhinoceroses; it might seem superfluous to say that there were not rhinoceroses, but, as a matter of fact, that family had a long and varied American history and became extinct only during or at the end of the Pliocene epoch. The horses were extremely numerous, both individually and specifically, and ranged, apparently in great herds, all over Mexico and the United States and even into Alaska. All the known species (at least 10 in number) belong to the genus Equus, but the true horse (Equus caballus) to which all the domestic breeds are referred, is not represented. The smallest known member of the genus is the pygmy Equus tau, of Mexico. [These ranged in size from ponies as large as a Shetland to horses that exceeded in size the heaviest modern draft horses.] * * * The Great Plains must have been fairly covered with enormous herds of horses, the countless bones and teeth of which, entombed in the Sheridan formation, have given to it the name of 'Equus beds.' * * *

"To one who knows nothing of the geological history of North America it would be natural to suppose that the Pleistocene horses must have been immigrants from the Old World which failed to establish themselves permanently here, since they completely disappeared before the discovery of the continent by Europeans. This would, however, be a mistaken inference, for North America was for long ages the chief area of development of the equine family, which may here be traced in almost unbroken continuity from the lower Eocene to the Pliocene. On the other hand, it is quite possible that some of the species were immigrants."

Tapirs, which are now confined to southern Asia, Central America, and South America, were abundant east of the Mississippi but are not known west of that river. Wild hogs, camels, and llamas were abundant. The hoofed animals, such as deer and bison, were numerous, and also the carnivores or flesh eaters. Conspicuous among these were the saber-toothed tigers (see Pl. II, A), which were contemporaneous with primitive man and doubtless were his formidable enemies. They have appealed so strongly to the imagination and have been referred to so often in literature that they are among the best known of the extinct animals.

The Pleistocene fauna was not without its grotesque features. Among the most curious animals of the time may be mentioned the ground sloths and the giant armadillos (Pl. II, C), of which Prof. Scott says:

"The ground sloths were great, unwieldy herbivorous animals covered with long hair, and in one family there was a close-set armor of pebble-like ossicles in the skin, not visible externally. They walked upon the outer edges of the feet, somewhat as the ant bear uses his fore paws, and must have been very slow moving creatures. Their enormous claws may have served partly as weapons of defense and were doubtless used also to drag down branches of trees and to dig roots and tubers. Apparently, the latest of these curious animals to survive was very large Megalonyx, which it is interesting to note was first discovered and named by Thomas Jefferson. The animals of this genus were very abundant in the forests east of the Mississippi River and on the Pacific coast, but much less common in the plains region, where they would seem to have been confined to the wooded river valleys. The still more gigantic Megatherium which had a body as large as that of an elephant and much shorter though more massive legs, was a southern animal and has not been found above South Carolina. Mylodon, smaller and lighter than the preceding genera, would seem to have entered the continent earlier and to have become extinct sooner. It ranged across the continent but was much commoner in the plains region and less so in the forested areas than Megalonyx, being no doubt better adapted to subsisting upon the vegetation of the plains and less dependent upon trees for food.

"The glyptodonts [armadillos see Pl. II, C] were undoubtedly present in the North American Pleistocene, but the remnants which have been collected so far are very fragmentary and quite insufficient to give us a definite conception of the number and variety of them." They were abundant, however, in the South American Pleistocene and hence are well known.

|

| FIGURE 1.—Sketch profile of river bluffs near Omaha, Nebr., showing the Aftonian gravels lying between two beds of glacial till and covered with thick deposits of loess. |

The Aftonian gravels separate two glacial deposits known as till, consisting of sandy clay in which are fragments of rock ranging from grains of sand to bowlders 2 feet or more in diameter. These fragments are of limestone, sandstone, quartz, and other rocks, but the largest and most conspicuous are of quartzite and granite, including blocks of a pink rock known as Sioux quartzite, because the rock mass from which they came is exposed near Sioux Falls, S. Dak. Many of the granite bowlders were carried by the glaciers hundreds of miles, for the nearest native rock of this kind occurs far to the north. (For description of glacial deposits see note on pp. 21-23.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006