|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

OGDEN, UTAH, TO YELLOWSTONE, MONT.

The route described in the following pages covers a distance of 291 miles on the Oregon Short Line Railroad from Ogden, Utah, across southeastern Idaho to Yellowstone, Mont., the west entrance to Yellowstone National Park,1 a public playground covering about 3,348 square miles. For 40 miles north from Ogden the road lies along the boundary between the Wasatch Mountains and the region once known as the Great American Desert, following the shore line of Lake Bonneville, a great body of fresh water that in geologically recent time covered a large part of Utah (pp. 97-99); then after turning eastward and passing through the range in a rocky canyon, it goes northward across a flat stretch of country which was the floor of a bay of the former lake. This bay was surrounded by mountains, and the railroad follows the foot of a north-south range to the head of an arm of the bay.

1Mileposts from Ogden to McCammon and from Pocatello to Idaho Falls give the distance north of Ogden; from McCammon to Pocatello, the distance west of Granger, Wyo.; and from Idaho Falls to Yellowstone, the distance north of Idaho Falls.

About 90 miles from Ogden the railroad crosses Red Rock Pass, through which for a time Lake Bonneville drained to the north, and then runs down a valley between two mountain ranges. In this valley the track for miles is on the surface or along the edge of a black lava flow. Turning west and passing through a notch in the Bannock Range, it comes out at Pocatello, 134 miles from Ogden, on the great Snake River plain. From Pocatello north for 100 miles the way leads across another lava flow, once a sagebrush waste, now an agricultural paradise. The last 50 miles of the route is through forests and finally over the Continental Divide, in mountains of volcanic rock poured out in the vicinity of Yellowstone Park.

|

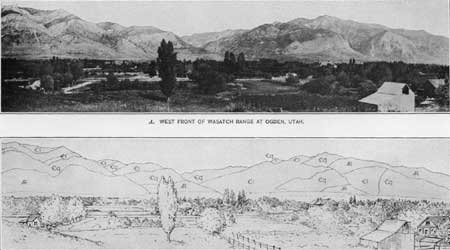

| PLATE XXVIII.—A (top), WEST FRONT OF WASATCH RANGE AT OGDEN, UTAH. B (bottom), DIAGRAM SHOWING GEOLOGY OF MOUNTAIN MASSES IN A. AR=Archean gneiss and schist; €q=Cambrian quartzite; €l=Cambrian limestone. |

The northbound trains, on leaving Ogden, cross Ogden River and come at once into orchards and into fields of sugar beets, hay, corn, and garden truck. From the outskirts of the city an uninterrupted view of the Wasatch Range can be had (Pl. XXVIII). Ogden Canyon is seen as a great notch with bare cliffs of pink quartzite on both sides, and tier on tier of gray limestone farther up the canyon.1 In the distance on the west is the hazy blue outline of Promontory Range, a long point extending from the north out into Great Salt Lake.

1The geologic structure of the Wasatch Mountains, from Ogden north to Brigham, has been described by Eliot Blackwelder as "shingled structure with overthrust slabs or wedges dipping eastward." (See fig. 13, p. 100.) Although this structure can not be seen from the railroad, the various formations can be distinguished. At the base of the range, showing above the lake benches, is the oldest rock formation here exposed, the Archean gneiss and schist, making dark-colored ragged ledges. (See Pl. XXVIII.) Above this is 1,000 feet of bare rock cliff of pale pink or faded iron-stain color, the Cambrian quartzite. Next higher, under brush and scattered trees, are ledges of gray limestone; then comes the pink quartzite again, and at the top a thick band of gray limestone. In the morning sunlight the west face of the range is somber and does not reveal the striking differences in these formations, but under the light of the afternoon sun they stand out in marked contrast.

The Cambrian quartzite can be traced by the eye from Ogden Canyon northward for several miles, but not continuously, for the rocks are broken by east-west as well as north-south faults.

The traveler who is for the first time west of the Rocky Mountains and wonders if the melodramatic activities of western life he has seen quivering on the "movie" screen really exist to-day along the route between Ogden and Yellowstone Park should remember Francis Parkman's introduction to "The Oregon Trail":

The buffalo is gone, and of all his millions nothing is left but bones. Fences of barbed wire supplant his boundless grazing grounds. Those discordant serenaders, the wolves, that howled at evening about the traveler's camp fire have succumbed to arsenic and hushed their savage music. The wild Indian is turned into an ugly caricature of his conqueror. The slow cavalcade of horsemen has disappeared before parlor cars and the effeminate comforts of modern travel. The all-daring and all-enduring trapper belongs to the past and the cowboy's star begins to wane. The wild West is tamed.

The great desert which Frémont explored in 1842 and to which the Mormons came in 1847 is still a desert, but orchards, gardens, and grain fields now mark its border.

|

|

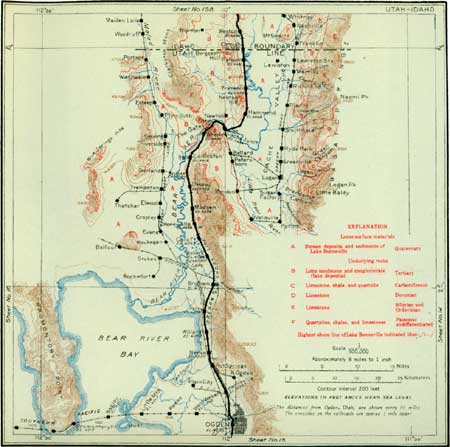

SHEET No. 15A. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Harrisville. Elevation 4,297 feet. Population 395.* Ogden 5 miles. |

A large brick plant at Harrisville (see sheet 15A, p. 114) is using clay that was deposited as sediment on the bottom of Lake Bonneville. This is one of the few mineral industries along this route. Many years of prospecting in the mountains all the way from Ogden to Yellowstone Park have brought to light a few small metalliferous deposits, but not one from which ore is being shipped. Among the nonmetals clay, sand, gravel, limestone, marl, coal, building stone, and water are utilized. Water is the one mineral to which above all others is due the prosperity of the country traversed by this route. Rock phosphate is a vast potential asset but is not yet used.

North of Harrisville a low ridge, strewn with many large angular blocks of rock, both white and pink, projects from the mountain front nearly to the railroad. This ridge is made of a great block of quartzite and limestone broken in two, the two parts standing on edge. A stone crusher working on one of the limestone ledges makes macadam for the highways.

The electric-car line between Ogden and Brigham and the main highway from Utah to Idaho are east of the track. There is a tomato-canning factory near Harrisville. Tomatoes are grown extensively all along the foothills between Ogden and Brigham, and in 1913 Brigham packed 30,000 cases; 24 cans to the case.

Just before reaching Hot Springs the train passes from Weber to Boxelder County and leaves behind the last saloon on the route, the country from Hot Springs to Yellowstone being "dry."

|

Hot Springs. Elevation 4,271 feet. Ogden 9 miles. |

The Utah Hot Springs hotel and sanitarium is a bathing resort that has some reputation for the relief of rheumatism. It is equipped with an open-air concrete pool 125 feet square, two indoor pools 28 by 45 feet, several smaller pools, and private baths. Small circular stone walls inclose the springs, which are just south of the station. The water, which is strongly charged with salt and other minerals, has a temperature of 131° F.

In this region there is a close relation between hot springs and lines of faulting. The temperature of the earth increases about 1° with every 50 feet of depth below the surface. Along the faults rocks which formerly were buried deeply and were therefore hot are now at the surface and water coming into contact with them a short distance below the surface, where they are still hot, is warmed; or the heat of the rocks may be due to friction along the fault plane.

Soon after passing Hot Springs the train runs close to a lagoon on the edge of Bear Bay, the northeast arm of Great Salt Lake. This lake, as is shown on pages 97-99, is a remnant of the much larger Lake Bonneville. Patches of white alkali (sodium sulphate and sodium chloride) may be seen along the edge of the lagoon and are due to the evaporation of salty water rising by capillary attraction.

A belt of land of varying width west of the railroad is in grain and pasture, but a strip close to the water is too salty to cultivate. The lagoon near Willard is often dotted with ducks and a flock of great white pelicans may usually be seen on the shore of the bay. The marshes and lagoons along the edge of the lake afford good hunting and many of them are owned by gun clubs.

The steel towers between the track and the lake carry the Utah Power & Light Co.'s high-power electric-transmission line, which extends from the Grace hydroelectric plant in Idaho to Salt Lake City.

On the east there are peach orchards, and back of them is the Wasatch Range, culminating in Ben Lomond Peak ("Willard Peak" of the Fortieth Parallel Survey). The terraces of Lake Bonneville carved in mountain waste deposited along the base of the range, are well preserved, and above them is the dark, rough-weathering gneiss. The Cambrian quartzite is very conspicuous here, forming a great pink band that extends far up the mountain side. The overlying limestone and shale, by reason of their softness, have weathered farther back than the much harder quartzite.

|

Willard. Elevation 4,260 feet. Population 577. Ogden 14 miles. |

Willard is a quiet old village, its main streets lined with poplars and its homes surrounded by orchards. The principal industry is the growing of peaches and tomatoes. The traveler who goes north to Yellowstone Park from Ogden will see many villages that were started by Mormon emigrants. Some of them are at the mouths of mountain canyons, where perennial streams afford water for irrigating the arid land near by. Willard was located near such a mountain stream, as were also Brigham, Wellsville, Logan, and other towns in this region.

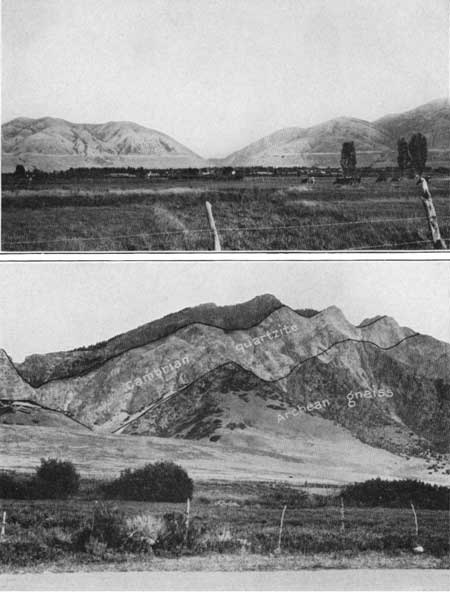

From Ben Lomond northward the pink Cambrian quartzite slopes down abruptly (Pl. XXIX, B), crosses the mouth of a sharp canyon back of Willard, where a stream leaps over it in a beautiful fall, and disappears under the terraces. The crest of the range also becomes lower, and the front of the range as far as Brigham shows older rocks (Algonkian quartzite and slate) thrust over the Cambrian. A short distance north of Willard Canyon the mountain face changes from bare crags to a fairly smooth grassy slope because the underlying rocks decay, so that the bedrock is covered by rubble in which vegetation soon gains a foothold.

|

| PLATE XXIX.—A (top), LAKE BONNEVILLE SHORE AT BRIGHAM, UTAH. B (bottom), CAMBRIAN QUARTZITE RESTING ON ARCHAEN GNEISS NEAR WILLARD, UTAH. |

North of Willard the old lake terraces are well preserved and peach orchards become more numerous. Among the trees in the distance is seen the white tower of a church in Brigham.

|

Brigham. Elevation 4,307 feet. Population 3,685. Ogden 21 miles. |

The first permanent settlers came to the mouth of Boxelder Canyon in 1853 and named the site of Brigham for their leader, Brigham Young. The Greens, Hunsackers, Johnstones, and Harrises were courageous folk, and although the level country was a great desert covered with sagebrush, they saw the advantages of the location, diverted the mountain stream into irrigating ditches, and transformed the desert into a veritable garden.

Brigham stands on a delta built in Lake Bonneville when the water was rising to the Provo level. (See p. 98.) When the lake was at its greatest height at the Bonneville level, the water extended back through Boxelder Canyon, drowned the river and made a bay of Mantua Valley, which lies within the range. During this time much of the material washed from the mountains around Mantua Valley was deposited in that valley and not carried through the canyon, which at that time held a quiet strait instead of a rapid stream. As the lake dried up the waves on its lowering surface cut terraces on the old delta, and a new Boxelder River came into existence and wore a channel down through the delta its ancestor had built. In summer Brigham, which is sometimes called Peach City, is almost completely hidden in peach orchards. The trees grow luxuriantly, because practically every street has an irrigating ditch for its entire length. About 400 acres of land beyond the reach of ditches from the canyon is irrigated from a score or more of wells pumped by electric motor. Brigham has celebrated Peach Day early in September annually since 1907. Peach Day is to Boxelder County what the 24th of July is to the State of Utah and the 4th of July to the Nation. On that day there are free peaches and plums and melons for all the thousands of people who visit the city. In 1913 this station shipped 467 cars of peaches. Tomatoes also are grown in large quantities. A factory near the station cans in the height of the season 60 to 75 tons of tomatoes every day.

The old transcontinental railroad line of the Central Pacific went west from Brigham over Promontory Range and around the north end of Great Salt Lake. It is little used now, for the trains go from Ogden straight across the lake. Brigham is the southern terminus of the Malade branch of the Oregon Short Line, which serves the west side of the Bear River valley.

As the train leaves Brigham going north the traveler gets a fine view of old lake beaches along the face of the mountain. (See Pl. XXIX, A.) The upper or Bonneville terrace is particularly conspicuous on each side of Boxelder Canyon.

A few miles to the west is Little Mountain, an isolated butte composed of limestone containing abundant fossil coral and shells. This butte was a small island when Lake Bonneville was at its greatest height. Six miles west of Brigham is Corrine, a station on the old main line of the Union Pacific Railroad, from which freight was hauled by wagon to the mines of western Montana in the early days. Then it had a population of nearly 5,000, but now it is only a small settlement. From Brigham to Idaho Falls the railroad parallels the road made by the freighters from Corrine. About 4 miles north of Brigham the railroad crosses Boxelder Lake, a small area covered with 1 inch or 2 inches of water, in which gulls, snipe, and plover are usually wading about. A State law prohibiting the killing of sea gulls at any time was passed many years ago, when these birds saved the emigrants' first crops from a scourge of grasshoppers.

|

Bakers. Elevation 4,222 feet. Ogden 25 miles. |

Just beyond this lake is Bakers sidetrack and the plant of the Ogden Portland Cement Co. This company owns a large area which was supposed for many years to be worthless on account of alkali, but which on testing by drill holes was found to be underlain by 2 to 8 feet of marl, a limy earth, averaging 85 per cent lime carbonate, beneath which is a bed of clay—an especially valuable combination, for the two materials together have the proper chemical composition for making Portland cement, and for a number of years the plant has been using them successfully. In 1914 it had an average daily production of 700 barrels. The company supplied some of the cement for the Arrowrock dam, built by the United States Reclamation Service near Boise, Idaho.

The broad brown and gray striping of the rugged mountain face north of Brigham is due to alternating shale and limestone formations.

At the 28-mile post the railroad passes under a steel transmission line carrying electric power from the plant of the Utah Power & Light Co. in Bear River canyon.

|

Honeyville. Elevation 4,266 feet. Ogden 30 miles. |

The residents of Honeyville are principally descendants of Bishop Abraham Hunsacker, the original settler, who was the father of 52 children. The name of the town is a euphonious corruption and shortening of Hunsackerville. About 2 miles north of Honeyville, in fields east of the railroad, are some weed-grown pools formed by hot springs that have been known for many years, though no commercial use of the water has yet been made. The water is salty, and strongly impregnated with iron and is described by a neighboring rancher as being "hot enough to scald a pig." Frémont reported the temperature of these springs at 134° Fahrenheit in 1843, and Gilbert found them varying from 121° to 132° in 1872. The discharge from the hot springs, mixed with water from cold springs in the same gully, is used for power at a gristmill on the bank of Bear River 1-1/2 miles west of Honeyville.

This part of Bear River valley is a former sagebrush desert that has been changed by irrigation1 to a thriving agricultural district in which large quantities of grain, alfalfa, sugar beets, potatoes, tomatoes, onions, and other vegetables are raised. It is said that this land has produced, per acre, 15 to 60 bushels of wheat, 65 to 135 bushels of oats, 50 to 95 bushels of barley, 6 to 8 tons of alfalfa, and 10 to 40 tons of beets. Apples, apricots, peaches, and plums are the principal fruits raised.

1To readers who are not familiar with irrigation a brief explanation may be of interest. The common practice is to select a site at the edge of the mountains, where, by throwing an inexpensive dam across a stream, the current may be diverted a little to one side, into a ditch where a headgate is placed and made secure by the use of bowlders or concrete. During the winter and high-water seasons the gate is kept closed, so that no water flows into the ditch, but in the dry season the gate is opened and a part of the stream is diverted from its natural channel. The headgate is, of course, far enough upstream to be at a higher altitude than the land to be irrigated, and the course of the ditch is determined by a more or less careful survey, so that it will have a uniform grade of a very few feet to the mile. As many of the streams of this region fall more than 100 feet to the mile, the height of the ditch above the valley bottom increases downstream, and for this reason in many ditches the water seems to be running uphill. As the upland inclines in the same direction as the stream, it is possible, without using any hoisting device, to locate the ditches so that water diverted from the stream at a certain point will flow out on the upland farther downstream—indeed, water can be carried in this way from one stream over a divide and down into another valley.

At the place where the water is to be used an opening is made in the downhill side of the ditch and the water is allowed to flow out over the land. In grain and hay fields care is taken to keep the water spread out in very thin sheets, by throwing earth in its pathway wherever there are little depressions in the surface and the water shows a tendency to get deep. In gardens and orchards the water is caused to flow down furrows between rows so arranged that it does not flow so fast as to wash away the soil. The immense acreage devoted to potato raising along this route is irrigated in this way.

On a perfectly level field it would be impossible to make use of this method of irrigation, but western fields usually have more or less slope, and hence it is possible, by guiding the water in its natural downward flow, to keep it spread out over the land either as a thin sheet or as little rills in closely spaced furrows. It is customary to allow the water to flow gradually across a field until it reaches the lower side, and then to stop up the opening in the ditch and make a new one near some other place which it is desired to irrigate. The time required for the water to reach the downhill side of a field is commonly several days, because the land absorbs so much of it.

In actual practice the method of irrigating is more complicated than that outlined here. According to the practice generally followed the water is not taken directly from the main ditch but from a branch.

|

Madsen. Elevation 4,298 feet. Ogden 33 miles. |

Madsen is only a siding and beet-loading platform. On the west is the cut bank of Bear River, which has carved a meandering course in the old lake bottom. The river is sluggish here, having nearly reached the level of the present lake, though several miles from it. As the train approaches Dewey prominent lake benches are seen on the mountain side.

|

Dewey. Elevation 4,323 feet. Population 292.* Ogden 36 miles. |

Three excavations on the hill a short distance back of Dewey were made in obtaining limestone for a million-dollar beet-sugar factory. Lime is used for removing various impurities from the beet-sugar juice. The four smokestacks of the factory can be seen about 3 miles to the west. To serve this sugar factory was the purpose of the branch railroad from Brigham to Malade. Sugar-beet growing is a large industry in this part of the valley, the area cultivated being 5,000 to 7,000 acres and the average production per acre 18 tons of beets. The factory can handle 600 tons of beets daily. It is on the edge of Garland, a village with a population of 800, which was named for William Garland, of Kansas City, the contractor for the construction of the irrigating canal through Bear River canyon.

The red color on the mountain side opposite Dewey is produced by a mixture of blue, gray, red, and pink limestone and limy sandstone. Just north of Dewey the traveler gets the first glimpse of Bear River, the largest stream draining into Great Salt Lake. This river has an interstate habit; it rises in southwestern Wyoming and is crossed by the Union Pacific Railroad near Evanston, flows northwestward into Utah, back into Wyoming, crosses into Idaho, and eventually turns southward to empty into Great Salt Lake. It also drains Bear Lake, a body of water 20 miles long lying across the Utah-Idaho boundary near the Wyoming line.1

1The mean discharge of Bear River near Preston, Idaho, is 1,290 second-feet (that is, 1,290 cubic feet of water a second). The total estimated possible power development on Bear River in the State of Idaho with the aid of storage is 81,500 horsepower. Three hydroelectric power plants are in operation on the river.

Irrigation is practiced throughout the length of Bear River valley wherever it has been possible to divert water from the stream at a reasonable cost.

Between Dewey and Collinston may be seen three conspicuous wave-cut terraces 300, 500, and 640 feet above the track; the uppermost one is the Bonneville and the lowermost the Provo terrace. Several miles to the west on a clear day the parallel beaches can be seen on the lower gentle slope of Blue Spring Ridge. Just before reaching Collinston the train leaves the flat lake floor and ascends through gravel cuts in an uneven surface to a slightly higher level.

|

Collinston. Elevation 4,416 feet. Population 114.* Ogden 40 miles. |

Collinston is a small settlement surrounded by grain fields. Lake terraces, like gigantic music staves engraved on the mountain, are beautifully preserved in this vicinity. The rocky knob just beyond the station is gray conglomerate (gravel and sand cemented together) of Tertiary age, carrying of an abundance fossil snail shells. This rock is very young in comparison with those found in the Wasatch Range and is the remnant of a once extensive body of gravel and sand which was deposited in a fresh-water inland sea that covered this area just prior to or during the uplifting of the mountains. Though geologically young, the rock in this knob is nevertheless hundreds of thousands if not millions of years old, and ever since its formation was completed and the lake was drained it has been subjected to the washing of the streams which have crossed it, so that much of it has been worn away. It has also been affected by movements within the earth, as is shown by the fact that its once nearly horizontal layers are now tilted and broken.

North of Collinston the railroad climbs by easy grades still higher above the plain, across which winds the deep-cut trench of Bear River. The broad valley continues northward and is occupied by Malade River, but the railroad turns eastward and goes through a canyon cut by Bear River across a low pass in the Wasatch Range.

The Utah-Idaho Sugar Co.'s canal, which irrigates the west side of the lower Bear River valley, is seen on the far side of the river and the Hammond canal on the near side. Although these canals appear to climb toward the west, they actually descend in that direction, for the irrigator has not yet learned how to get around gravitation without lifting devices, and in Utah, as everywhere else, water runs downhill.

|

Wheelon. Elevation 4,499 feet. Ogden 44 miles. |

The Utah Power & Light Co.'s 4,000-horsepower electric plant, with its great flumes taking water from these canals, is on the river bank at the mouth of the canyon. The railroad station was named for John C. Wheelon, a civil engineer who constructed part of the canal.

Such scenery as that for the 2 miles above Wheelon is to be found at no other place on the railroad between Ogden and Yellowstone. Here is one of the two tunnels on the route; here are the highest trestles and the sharpest curves. With a great flume of water just below the track and Bear River roaring over bowlders that impede its progress along the canyon bottom 175 feet below, this is no place for speeding; and yet the time consumed in going through the canyon is so short that one can only glance at the numerous interesting geologic features. It is easy to see that the narrow canyon, with its high precipitous walls, is cut in limestone whose beds dip about 25° to the west; but there is little likelihood that the traveler will notice the cavities made by solution of the limestone or the numerous small faults which break the normal continuity of the rock beds. He will, however, be attracted by a waterfall made by the overflow from a flume below the track and by the low falls in the river.

At the upper end of the canyon, just below the dam which diverts the water of the river into flumes, pink quartzite is exposed below the limestone. Above the dam green Tertiary shales are seen in the opposite wall. These shales are the hardened mud which was laid down on the bottom of a lake that covered this area before the mountains were formed or while their elevation was in progress. That they are older than Lake Bonneville is shown by their continuation beneath the silts deposited in that lake, and that they are older than the mountain uplift is proved by the facts that their original continuity is broken by a mountain-forming fault, and that they were hoisted and tilted from their original position along with the mountain block.

|

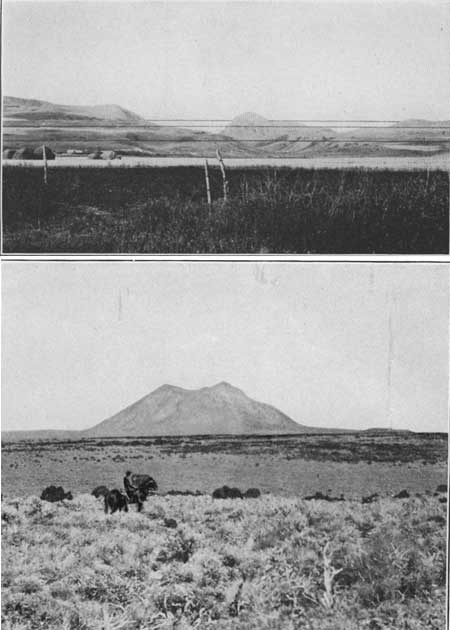

| PLATE XXX.—A (top), "THE GATES" OF BEAR RIVER, FROM THE EAST NEAR CACHE JUNCTION, UTAH. Horizontal lines indicate wave-cut shore lines of ancient Lake Bonneville. B (bottom), EAST BUTTE, IDAHO. |

The steel-tower transmission line that crosses the hill brings electricity from a power plant in the upper Bear River canyon 20 miles above Preston, Idaho. On leaving the canyon the train swings around a bend and enters the broad Cache Valley,1 of which the Bear River range, another part of the Wasatch Range, makes the east wall. To the northeast is Newton Hill, which was an island in the great arm of Lake Bonneville that occupied this valley. Wave-cut shore lines are conspicuous on its sides (see Pl. XXX, A), showing conclusively that Cache Valley was once occupied by a great body of water several hundred feet deep. It will be easily realized that when Lake Bonneville was at its greatest height the strait between the body of water in Cache Valley and the larger body on the west was about 5 miles wide and was shallow and interrupted by several islands. The cliffs of the narrow canyon reach nearly to the level of the second conspicuous terrace (the Provo), and north of the cliffs, where the highway now crosses the pass, there is a considerable break in the upper (Bonneville) terrace, as there is also south of the canyon. From this it appears that as the lake surface lowered the outlet of Cache Bay dwindled to three channels. One of these whose position may have been determined by a fault or line of fracture across the pass persisted and now carries all the drainage. While the canyon was being cut, the surface of the main lake must have been lower than that of Cache Bay. The smaller body of water, besides evaporating less rapidly, was receiving the largest inflow. When the shore of the main lake had receded a considerable distance, perhaps several miles from the mouth of the canyon, Cache Valley no longer contained a bay connected with the main lake by a narrow strait, but instead a separate lake which drained into Lake Bonneville by a short river. Eventually the lake in Cache Valley was drained out, and the river flowing across the abandoned lake bottom west of the canyon has gradually deepened its channel.

1Cache Valley was formed by faults which broke the earth's crust into blocks and raised some with relation to others. The Wasatch Range has already been described (pp. 99-100) as made of upturned slabs of rock formations shoved up one on another. The Bear River Range had somewhat the same origin. The west face at Logan is believed to be a fault scarp like that at Ogden. Whether the block under Cache Valley remained at a fixed altitude while the surrounding blocks were raised, or whether it sank with relation to them is not known. The surface of the valley block probably was not smooth, but when Lake Bonneville occupied this basin, the sediment brought in by rivers, and the wash from the mountain sides, were deposited on the lake bottom and smoothed over the inequalities, making the present nearly level surface.

|

Cache Junction. Elevation 4,444 feet. Ogden 49 miles. |

From Cache Junction the Cache Valley branch of the railroad runs to Wellsville, Logan, and Preston. The bottom of Cache Valley has an altitude of about 4,500 feet and presents one of the most beautiful pastoral spectacles in the State. The valley proper is about 35 miles long and in many places 10 miles wide. The settlement of this valley was begun by the Mormons in 1856, when the town of Wellsville was laid out by a colony of six families. White persons had, however, been here before. J. C. Frémont, in the report of his explorations in 1842, mentions meeting parties of emigrants in this locality, and Marcus Whitman traversed the valley in the fall of 1842 on his memorable journey from Oregon to Washington, D. C., with the object of saving Oregon Territory for the United States.

Logan, the principal town in Cache Valley, has a population of about 8,000 and is the location of the State Agricultural College, Brigham Young College, and one of the four great Mormon temples. The two towers of this temple, rising above the treetops at the foot of the mountains to the east, can be seen from the railroad. Two large sugar factories in this valley, at Logan and at Lewiston, contract for the yield of several thousand acres of sugar beets, the growing of which is one of the principal industries. Dairying is also an extensive industry and condensed-milk factories are located at Logan, Smithfield, Richmond, and Franklin.

On leaving Cache Junction the train crosses Bear River and turns to the north, giving a broad view of the south end of Cache Valley and its encircling mountains. Logan Peak, the highest point on the range near Logan, has an altitude of 9,713 feet. The strip of timber along the foot of the mountains from Logan north is not natural forest but is composed wholly of orchards, shade trees, and windbreaks around the farms.

|

Hammond. Elevation 4,448 feet. Ogden 53 miles. |

Wave-cut terraces or beaches of old Lake Bonneville are well preserved on the side of Newton Hill, west of Hammond siding. The rock cliff here probably is the results of comparatively recent uplift along a north-south fault. Between Hammond and Trenton, at the point where the railroad turns from northeast to north, the white spots that look like closely set gravestones on the hillside west of the track are about 200 beehives. The bees feed on alfalfa and white clover, and the honey industry is growing. Many years ago the Mormons attempted to establish a silk industry in the valley but were not successful. Some of the mulberry trees they set out are still standing.

|

Trenton. Elevation 4,460 feet. Population 248.* Ogden 57 miles. |

The principal industry of Trenton is indicated by the grain elevators and large flour mills. Most of the ridge on the west is formed of soft sandy and limy rocks of Tertiary age. Some houses in the vicinity are built of these rocks, which are easily quarried and shaped. North of Trenton well-developed lake terraces may be seen on the ridge to the west, and in the late afternoon sunlight they are made particularly conspicuous by the shadows. To the east stretches a broad, level plain, the built-up floor of Cache Bay of the ancient Lake Bonneville.

Most of the villages in the valley are at the foot of then mountains on either side. The settlement of an arid country depends on then water supply, and as then best and most usable water was found at the mouths of mountain canyons, there the pioneers built their homes. The center of the broad valley is thinly settled, largely because Bear River and its tributaries have cut their channels so deep below the general level that it is hard to get water from them up on the land.

|

Ransom. Elevation 4,481 feet. Ogden 61 miles. |

Ransom is only a railroad siding. Several miles to the northeast, in the broad valley of Bear River,1 is the town of Preston, which has a population of about 3,000 and is the terminus of the Cache Valley branch of the Oregon Short Line. Hidden in the trees to the right of an isolated hill on the east side of Bear River is the village of Franklin. This hill, which is 6 miles east of the railroad, is a knob of limestone known as Mount Smart ("Franklin Butte" in Gilbert's report on Lake Bonneville; see p. 230) and was an island in Lake Bonneville. The story of that lake is carved in unmistakable signs on what was the windward side of this island. Cliffs cut by the waves that once beat against it and beaches covered with gravel are beautifully preserved on the southwest side, toward what was a broad expanse of open lake, while the east or shoreward side is comparatively smooth. Lime for the beet-sugar factories in this valley has been quarried in this hill.

1The mean discharge of Bear River as determined by measurements of its flow made at Preston, Idaho, during a period of 24 years, is 1,290 second-feet—that is, 1,290 cubic feet of water passing a given point each second. A maximum flow of 7,980 second-feet was recorded in 1894, and a minimum of 164 second-feet in 1905. There are two hydroelectric plants on Bear River above Preston, one under construction in Oneida Narrows, to have an installed capacity of 27,000 horsepower, and one at Grace, Idaho, with 17,000 horsepower.

|

Cornish, Utah. Elevation 4,522 feet. Population 143.* Ogden 62 miles. Idaho. |

At Cornish the train leaves Utah and enters the State of Idaho. The station stands on the State line. The irrigation canal seen at Cornish is 19 miles long, heads on Bear River above Battle Creek, 12 miles to the north, and supplies water for 20,000 acres of otherwise desert land. The irrigation systems in this valley were built and are owned by private companies.

To those who remember Idaho in their school geographies as a small pink block, shaped like an easy chair facing east, it may be of interest that this State, which in 1890 added the forty-fifth star to the constellation on the flag, is nearly as large as Pennsylvania and Ohio combined and larger than the six New England States with Maryland included for good measure. It is divided into 33 counties, the smallest of which is half as large as the State of Rhode Island and the largest greater than the combined area of Massachusetts and Delaware.

Idaho covers an area of 83,888 square miles, divided principally between the Rocky Mountain region and the Columbia Plateau, only a small part, in the southeast corner of the State, lying in the Great Basin. In elevation above sea level the State ranges from 735 feet, at Lewiston, to 12,078 feet at the summit of Hyndman Peak. It is drained mainly to the Columbia through Snake River and its tributaries, and has an annual rainfall of about 17 inches, the range in a single year at different places being from 6 to 38 inches.

The industries of the State are chiefly agriculture, stock raising, and mining. Hay, wheat, oats, and potatoes are the principal crops. A large area is cultivated by irrigation. The mineral production includes gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc. The output of lead in 1913 was valued at $13,986,366, that of silver at $6,033,473.

The population of Idaho in 1910 was 325,924.

|

Weston, Idaho. Elevation 4,604 feet. Population 398. Ogden 65 miles. |

A short distance from Weston the steel-tower electric line, which conveys power from the upper canyon of Bear River and which was last seen by the traveler at Bear River canyon, again crosses the railroad. Weston is an old Mormon village on the lake terrace west of the station. North of it the railroad ascends a slight grade, and the gullies cut in the lake deposit give the surface an uneven appearance, but on the upper level it is very apparent that the plain is only slightly dissected. In the distance to the northeast is a high-cut bank of Bear River, but the river is not in view because in this part of its course it has sunk its channel in the easily eroded lake deposits to a depth of 250 feet below the plain.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec20.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006