|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

OGDEN, UTAH, TO SAN FRANCISCO, CAL.

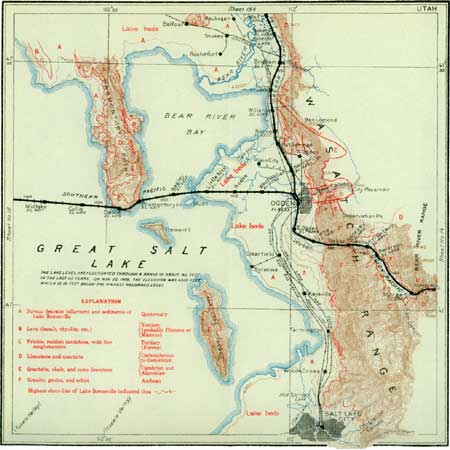

The railroad leaves Ogden (see sheet 15, p. 102) in a northwesterly direction and follows for a mile or more the old line of the Central Pacific Railway, which made a considerable detour around the north end of Great Salt Lake. At milepost 7811 the present line diverges from the original route and, swinging gradually westward, turns directly away from the great mountain wall of the Wasatch Range. It is 15 miles from Ogden to the eastern shore of Great Salt Lake, and for 32 miles beyond this point the way lies directly across the lake to its western shore.

1Mileage along the route is marked by milepost boards on telegraph poles and numbers on semaphore signals, culverts, and bridges. The figures given represent distance from San Francisco and show the westbound traveler how far he still must go.

|

|

SHEET No. 15. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As the train goes toward the lake the view from the rear, or observation platform, is one of the finest panoramas of mountain scenery to be had from the railroad, especially if the light and weather are favorable. Just back of Ogden appears an almost sheer mountain wall of dark and rugged ridges standing above the flat valley in the foreground. Such an abrupt face on one side is more or less typical of the Great Basin mountains and is believed to be significant of the manner in which they have been formed. There is little doubt that these mountains have originated by fracture of the earth's crust and uplift along one side or settling along the other side of the crack. In geologic terms, the mountains are upheaved fault blocks. Since the faulting the forces of erosion have more or less rounded and scored the original cliff or scarp made by the break. The deep notch across the range in the middle background is the canyon of Ogden River, which flows into Weber River a few miles below Ogden.

The railroad extends across the level lands that border the east side of Great Salt Lake. For several miles most of this land is cultivated and is richly productive after it has been "broken"—that is, after it has been plowed and partly leached of its alkali salts by irrigation. The common crops are hay, grain, sugar beets, and vegetables. Tomatoes raised here are canned in considerable quantity. In certain favorable situations along the foot of the mountains peaches, apples, and other fruits are grown.

Near milepost 778 a line of steel towers of an electric-power transmission line crosses the railroad from north to south. This conveys current from large hydroelectric plants on Bear River, near Collinston, 20 miles north of the lake, straight across the meadow flats to Salt Lake City and beyond to the Bingham mines and to the smelter at Garfield.

|

West Weber, Utah. Elevation 4,240 feet. Population 823.* Omaha 1,006 miles. |

West Weber (see sheet 15, p. 102) is a farming community in the midst of a broad, gently sloping plain, where water for irrigation may be distributed by ditches almost anywhere. Artesian wells bored along this side of the lake, to a depth of 300 or 400 feet, yield natural flows of pure, fresh water that has come down from the mountains in porous layers of rock that lie underneath some relatively impervious layer. Along the east side of the lake this fresh water may even be tapped in wells put down through the salt water of the lake itself. Beyond West Weber the ground becomes more and more salty on the surface, and the cultivated lands diminish in area, the salty meadows or marshes being used for pasture. A few miles farther west the ground, during the dry season, is white with crusted salt.

Little Mountain, the name of a railroad siding at milepost 769, refers to the low, rounded terraced hill north of the track. The terraces here, as on the islands in Great Salt Lake and around Promontory Point, mark old shore lines of Lake Bonneville, described on pages 97-99. To the south, near the shore of the lake, are the remains of evaporation vats, formerly used in the manufacture of salt by crystallization from the water of the lake. The industry of this place was ended by a general rise in the lake level during recent years (see fig. 11, p. 95), but large quantities of salt are still manufactured near Saltair, at the south end of the lake.

The building of the Lucin cut-off, completed in 1903, was an epoch-making event in railroad construction. By this great fill and trestle straight across Great Salt Lake the main-line route from Ogden to San Francisco was shortened about 44 miles and the steep and troublesome grades around the north end of the lake, including one climb of 680 feet to the old Promontory summit, were eliminated. The new line is level for 36 miles and the grade is almost inappreciable for 36 miles more, being nowhere over 21 feet to the mile, or less than 0.5 per cent.

The cut-off was constructed at first as a gravel fill across the shallow marginal portions of the lake and as trestle work through the deeper part. Much of the trestle work has since been replaced by fill. The gravel used at first came from pits near the railroad, the largest of which was near the west side of Promontory Point. Rock was originally used only on the surface of the embankment, but later, in places where reconstruction was necessary, rock was employed exclusively. The rock has been obtained from Promontory Point and from the immense quarries near Lakeside. The dark-gray, almost black limestone from the Lakeside quarries now covers the surface of the fill all the way across the lake.

An unexpected difficulty was encountered after the construction was well under way. It was found that the material which was dumped into the lake and which evidently sank deep into the mud did not at once reach a firm and permanent foundation. Long after the roadway had apparently been completed and trains had been run by way of the new route, successive "sinks" occurred, especially along certain portions of the route. The weight of the filling material, with the added weight and vibration of passing trains, seemed to break through some sustaining layer in the lake bottom and then a whole section, track and all, would settle into the lake, and traffic would have to be diverted to the old route until the "sink" could be repaired. This happened so frequently that it might fairly have discouraged the railroad company, but perseverance finally conquered. With the sinking of the track, ridges of mud appeared on both sides, squeezed up from the lake bottom by the subsiding fill. Just beyond Bagley, which is only a section house and side track on the cut-off, remnants of these mud ridges can still be seen, although, naturally, where they rise above the water they are being leveled by the waves. The elevation of the track across the cut-off is 4,217 feet above sea level according to railroad figures; the lake is usually 10 to 15 feet lower.

A channel of open water 600 feet wide under a trestle at milepost 762 is now the only connection between Bear River bay and the main lake. As Bear River, the largest tributary of Great Salt Lake, enters at the north side of this bay, and as more water is evaporated from the main lake than from the bay, there is usually a flow of water from the bay into the lake through this passage. The water of Bear River bay has for this reason become so much fresher that lately it has frequently frozen over to considerable thickness during the winter.

The view toward Ogden and the Wasatch Mountains expands as the train proceeds. The high summit above Ogden is Observation Peak, 10,103 feet above sea level; Ben Lomond, the summit on the long, high ridge farther north, is still higher (10,900 feet). The upper shore lines of the former Lake Bonneville show distinctly as a series of clearly defined terraces on Promontory Point and also around Fremont Island. On Fremont Island only a single little point like a cap, undercut by wave action on all sides, rises above the highest water level of the old lake.

Milepost 759 is just at the west edge of the first section of the fill, the section that crosses Bear River bay. This eastern part of the cut-off is 8 miles long. The track skirts the south shore of Promontory Point for 4-1/2 miles and then runs out on the second section of the fill, which is over 20 miles long.

|

Promontory Point. Elevation 4,217 feet. Omaha 1,023 miles. |

The station at Promontory Point (see sheet 15, p. 102) is maintained chiefly for purposes of railroad operation. Rock and gravel for building the embankment across the lake were obtained at several places along the south end of the point. The rock exposed in railroad cuts and quarries here is a black slate, which weathers rusty and brown.

Just west of Promontory Point station, on the north side of the track, is a pond cut off from the lake by the railroad embankment. At times of high water in the lake this reservoir fills by percolation through the enbankment, and during the summer this water is concentrated to a brine by evaporation. The deep pink color of the brine is a phenomenon that appears in salt ponds generally when a certain concentration is reached. In the salt ponds of San Francisco Bay this color is due to a certain bacillus which lives in saturated brines and also in the heaps of salt as it is piled for drainage and shipment. Prohibitive to life as such an environment might be considered, strong natural brines are, in fact, inhabited by a number of minute organisms—animals as well as plants. The pink color disappears in winter or when fresh water is introduced into the pond. The railroad company has done some experimental work on preserving piles and ties by soaking them in this pond.

Beyond the pond the track follows the lake shore along the south end of Promontory Point for a mile or two, passing a minor station and group of railroad section houses called Saline.

Looking a little east of south from Promontory Point, one can see on the south shore of Great Salt Lake the town of Garfield, the concentrating mills of the Utah Copper Co., and the copper smelter of the Garfield Smelting Co. A long column of smoke may usually be seen trailing away over the mountains from the smelter stack. These plants were constructed a few years ago to treat copper ores from Bingham Canyon, a short distance to the south, in the Oquirrh Range, and the town of Garfield was established to furnish accommodations for the men employed at the mills and smelter. The two mills of the Utah Copper Co. are among the largest concentrating plants in the world and together are capable of treating over 20,000 tons of ore daily. The ore treated contains an average of about 1.5 per cent of copper in the form of sulphides.

At the semaphore marked 754.5 miles the railroad runs out on the fill across the west arm of the lake. Large excavations near by are in the "gravel" that was at first used in constructing the fill. This "gravel" is of a very unusual character. If examined closely, preferably with a magnifying glass, it is found to consist of smoothly rounded, opaque grains, not like ordinary sand grains. These are known as oolites, the word oolite meaning literally fish-egg stone or roe stone. Each oolite is built up, onion-like, of one layer over another. These layers consist of carbonate of lime chemically deposited from solution in the lake water. There is almost no lime in the water of Great Salt Lake as a whole, as the brine seems to be too strong in other more soluble salts to retain the less soluble carbonate. Waters sweeping into the lake around its margin and the tributary river waters, however, contain a considerable amount of lime, and this on mixing with the lake water is deposited on the bottom in the form of these oolitic grains. The grains may be compared to little pearls, which in fact they resemble both in composition and structure. It has been shown that minute plants (algae or bacteria) have had much to do with the manner in which this lime is precipitated; but that is another story, too long to tell here.

A mile and a half farther west the road runs across deeper water, the track here being on a trestle, which continues for about 12 miles. The surface or deck of the trestle is ballasted with rock, so that it is not very different in appearance from the solid fill.

From the railroad the islands in Great Salt Lake come successively into view. Fremont Island has already been referred to. Antelope Island, a submerged mountain of considerable size, is south of Fremont. Stansbury Island (with twin peaks on the summit) may be seen in the distance at the south end of the lake. Far to the south also are Camington Island and Hat or Bird Island. North of the railroad are Gunnison and Dolphin islands and Strong Knob, which was formerly an island but has lately been connected with the mainland by a narrow spit. A double track with station and railroad section houses has been built on the trestle out in the middle of the lake, where the water is reported to be 42 feet deep. The station is called Midlake. Between this station and Lakeside is Rambo.

|

Midlake. Elevation 4,217 feet. Omaha 1,037 miles. |

Near milepost 735 the railroad reaches the west shore and passes through a cut in limestone rock, beyond which is a great cliff of blue limestone in thick beds that dip toward the southeast. These rocks are of Paleozoic age, the dark-blue to black limestones near Lakeside belonging to the Carboniferous period. (See table on p. 2.) The range lying along the west shore of Great Salt Lake is known as the Lakeside Mountains.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec24.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006