|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

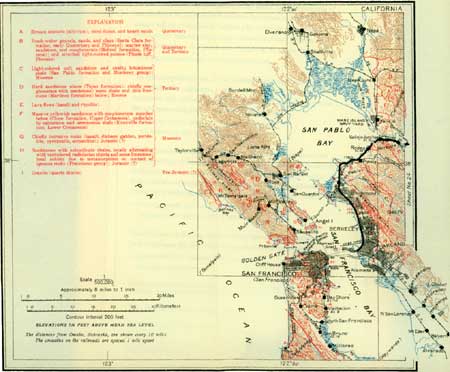

SHEET No. 25. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Port Costa. Elevation 11 feet. Omaha 1,750 miles. |

Port Costa (see sheet 25, p. 224), the western ferry terminus, is a shipping point, particularly for grain, which comes from the extensive grain-producing district in the valley1 and is here loaded into ocean-going vessels. A long line of galvanized-iron grain warehouses may be seen on the water front.

1Agriculture in California had its beginning in wheat raising, and wheat was long the State's greatest crop. Its production steadily increased until about 1884, to over 54,000,000 bushels annually. The levelness of the great grain fields of the valley led to the utilization of combined harvesters, steam gang plows, and other farm machinery of extraordinary size and efficiency. Recently, however, fruit growing has become a more important industry than grain farming. In the value of its fruit crop California leads all the other States.

On leaving Port Costa the train skirts the south shore of Carquinez Strait, where the steep bluffs offer many good exposures of folded sedimentary rocks. The first rocks seen are Upper Cretaceous (Chico) sandstone and shale. The rocks have a moderately steep westward dip and trend almost directly across the course of the railroad, so that as the train proceeds successively younger formations are crossed. At Eckley, a short distance beyond Port Costa, brick is manufactured from the Cretaceous shale. At Crocket is a large sugar refinery. Mare Island, across Carquinez Strait, is the site of the United States navy yard, which, however, is not readily discerned from this point. The Cretaceous shales and sandstones continue to Vallejo Junction and a little beyond.

On the southeast side of San Pablo Bay, near the west end of Carquinez Strait, there are wave-cut terraces and elevated deposits of marine shells of species that are still living. These terraces and deposits do not show south of San Pablo Bay, and therefore seem to indicate the recent elevation of a block including only a portion of the shore around the bay. This block probably includes the Berkeley Hills and a considerable territory to the east, perhaps even extending to Suisun Bay.

|

Vallejo Junction. Elevation 12 feet. Omaha 1,754 miles. |

From Vallejo Junction a ferry plies to Vallejo (val-yay'ho), which is on the mainland opposite the navy yard, and from which railroad lines extend into the rich Napa and Sonoma valleys. Santa Rosa, the home of the famous Luther Burbank, is in the Sonoma Valley. Vallejo was named from Gen. Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, who played a prominent part in the early history of California. It was the capital of the State from 1851 to 1853. Beyond Vallejo Junction Carquinez Strait begins to open out into San Pablo Bay.1

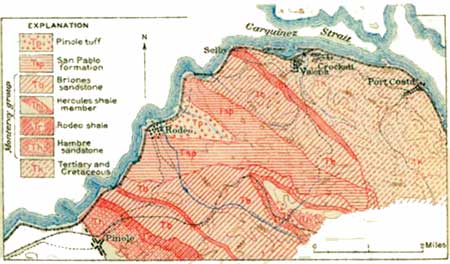

1The section along the shore of San Pablo Bay between Vallejo Junction and Pinole (see figs. 19 and 20, on sheet 25, p. 224) includes six of the most widespread divisions of the sedimentary series in the Coast Range region of California. The formations or groups represented are the Chico (Upper Cretaceous), Martinez, (Eocene), Monterey (earlier Miocene), San Pablo (later Miocene), Pinole tuff (Pliocene), and Pleistocene. The only large divisions of the middle Coast Range sequence not represented are the Franciscan (Jurassic?), Tejon (Eocene), and Oligocene, all of which are found within a few miles to the east and south.

FIGURE 19.—MAP SHOWING GEOLOGIC FORMATIONS ALONG THE SOUTH SHORE OF SAN PABLO BAY.

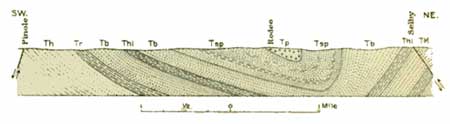

FIGURE 20.—SECTION SHOWING STRUCTURE ALONG THE SOUTH SHORE OF SAN PABLO BAY. In the San Pablo Bay section all the formations below the Pleistocene are included in a syncline, on the northeast side of which the strata are nearly vertical, but on the southeast side the dip of the beds is lower. The Pleistocene beds rest horizontally across the truncated edges of the Miocene and Pliocene. The aggregate thickness of the sediments in the San Pablo Bay section is not less than 8,000 feet. With the exception of the Pliocene and a portion of the Pleistocene, all the formations are of marine origin. A portion of the Pinole tuff was certainly deposited in fresh water. The Pleistocene beds were deposited under varying marine, estuarine, and fluvial conditions.

Fossil remains are found in all the formations of the San Pablo Bay section, and at least six distinct faunas are represented. Very few specimens have been procured in the Chico near the line of the railroad, but abundant fossils are found in the same formation a few miles to the east. The Martinez fauna is represented in the cliff opposite the Selby smelter. The Monterey and the San Pablo contain abundant remains. The fresh-water fauna of the Pinole tuff is represented by molluscan species. Leaves and remains of vertebrates are also present. The Pleistocene shale contains abundant marine shells of a few species, with mammal bones representing the elephant, horse, camel, bison, ground sloth, antelope, lion, wolf, and other forms.

The dark Cretaceous shales near the railroad station at Vallejo Junction are soon succeeded by brown shales and massive sandstones belonging higher in the Cretaceous system. The contact between the Chico and the Martinez (Eocene) beds is in a fault zone cut by the railroad tunnel a short distance west of Vallejo Junction. Just beyond the tunnel the contact between the Martinez and the Monterey (Miocene) is clearly shown in a high cliff to the left, opposite the Selby Smelting Works, where the buff-colored Monterey sandstones and shales rest with marked unconformity upon the black Eocene shales. Near the contact the Eocene shale is filled with innumerable fossil shells of boring Miocene mollusks. The Monterey beds are extraordinarily well exposed in the cliffs to the left, and immediately beyond the contact, where they consist of fine buff shales with shaly sandstones and thin bands of yellow limestone.

After leaving these cliff exposures the train passes Tormey station, crosses a little swamp, and approaches a tunnel cut into vertical cliffs of massive gray sandstone; this is the type locality of the San Pablo formation (upper Miocene). The refining plant of the Union Oil Co., at the east end of this tunnel, is located on the upper part of the San Pablo beds. Vertical beds of massive tuff immediately west of the oil refinery represent the lower part of the Pinole tuff. Beyond these beds the train crosses another swamp and enters a cut in which white volcanic ash beds of the Pinole tuff dip at a relatively low angle to the northeast. This change in dip shows that these beds are on the southwest side of the San Pablo Bay syncline, the axis of which passes through the swamp area. Resting upon the tilted ash deposits in this part of the section are horizontal beds of Pleistocene shale.

|

Rodeo. Elevation 12 feet. Omaha 1,757 miles. |

The name Rodeo (ro-day'o), meaning "round-up," indicates that the station so called was formerly a cattle-shipping point. Beyond Rodeo the train enters a series of cuts. Near the station are exposures of massive tuffs close to the base of the Pinole tuff. Beyond this point the San Pablo (Miocene) appears, with low dips to the northeast. In the sea cliffs on San Pablo Bay a few yards from the railroad are excellent exposures of the Miocene capped by Pleistocene shale. At Hercules, where there are large powder works, the railroad cut is in broken shale of the Monterey group, the same beds that were seen near the Selby smelter, on the northeast side of the syncline. Beyond Hercules the railroad passes over Monterey shale to the town of Pinole (pee-no'lay, a Spanish term used by the Indians for parched grain or seeds), where the Pinole tuff is in contact with the Monterey and is covered by a thick mantle of the Pleistocene shale. In the cuts southwest of Pinole the rocks exposed are all either steeply inclined Pliocene tuffs or horizontal Pleistocene beds.

|

Pinole. Population 798. Omaha 1,760 miles. |

At Krieger, where the tracks of the Santa Fe route may be seen approaching the bay front from the south, is a so-called "tank farm." The oil-storage tanks, which belong to the Standard Oil Co., are beyond the Santa Fe line. Beyond Sobrante station is Giant, another powder factory, and beyond that are pottery works which obtain clay from Ione, in the Sierra Nevada. The bay shore near Oakland is largely given over to industrial uses, on account of its facilities for rail and water transportation.

|

San Pablo. Elevation 30 feet. Omaha 1,765 miles. |

Beyond Giant the foothills retreat from the bay shore and the railroad enters the broad lowland on which the cities of Berkeley and Oakland are built. Near San Pablo, in the vicinity of San Pablo and Wildcat creeks, there is a gravel-filled basin. Many wells sunk in this gravel may be seen near the tracks, and from them a municipal water company and both railroads obtain water. West and southwest of San Pablo station a line of hills shuts out a view of San Francisco Bay. These hills constitute the Potrero San Pablo, so called because, being separated from the mainland by marshes, they were a convenient place in which to pasture horses during the days of Mexican rule, when fences were practically unknown. The hills are made up wholly of sandstone belonging to the Franciscan group.1 On the other side of them are wharves, warehouses, and large railway shops belonging to the Santa Fe system. From that side also the Santa Fe ferry plies to San Francisco.

1The rocks of the Franciscan group comprise sandstone, conglomerate, shale, and local masses of varicolored thin-bedded flinty rocks. The flinty rocks consist largely of the siliceous skeletons of minute marine animals, low in the scale of life, known as Radiolaria, and on this account they are known to geologists as radiolarian cherts. All the rocks mentioned have been intruded here and there by dark igneous rocks (diabase, peridotite, etc.), which generally contain a good deal of magnesia and iron but little silica. The peridotites and related igneous rocks have in large part undergone a chemical and mineralogic change into the rock known as serpentine. Closely associated with the serpentine as a rule are masses of crystalline laminated rock that consist largely of the beautiful blue mineral glaucophane and for that reason are called glaucophane schist. Schist of this character is known in comparatively few parts of the world, but is very characteristic of the Franciscan group. It has been formed from other rocks through the chemical action known as contact metamorphism, set up by adjacent freshly intruded igneous rocks. The Franciscan group is one of the most widespread and interesting assemblages of rocks in the Coast Ranges.

|

Richmond. Population 6,802. Omaha 1,767 miles. |

Richmond, on both the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe lines, is becoming a busy shipping, railroad, and manufacturing point, on account of the congestion of the water front of Oakland and San Francisco. The hills on the east side of the track, known to old Californians as the Contra Costa Hills, but now often referred to as the Berkeley Hills, rise steeply from the plain. The most conspicuous summit from the West is Grizzly Peak (1,759 feet), but Bald Peak, just east of it, is 171 feet higher. The hills are generally treeless on their exposed western slopes, although their ravines and the eastern slopes are wooded.1

1The geologic structure of these hills is rather complicated. Along their southwest base, between Berkeley and Oakland, is a belt of the sandstones, cherts, and schists belonging to the Franciscan (Jurassic?) group and characteristically associated with masses of serpentine. Overlying the Franciscan rocks are sandstones, shales and conglomerates of Cretaceous, Eocene, and Miocene age. These in turn are overlain by tuffs, fresh water beds, and lavas of Pliocene and early Quaternary age. The general structure of the ridge east of Berkeley is synclinal, the beds on both sides dipping into the hills. The upper part of Grizzly Peak is formed chiefly of lava flows of Pliocene age.

Beyond San Pablo and Richmond the rocks of the Franciscan group outcrop in low hills. At Stege the railroad is still close to the shore of the bay. Between this place and the hills is one of the suburbs of Berkeley known as Thousand Oaks. The traveler can get here an unobstructed view out over the bay and through the Golden Gate. Mount Tamalpais is on the right and San Francisco on the left. Just to the left of the Golden Gate the white buildings of the Exposition grounds can readily be distinguished if the day is at all clear. At Nobel station a little wooded hill of Franciscan rocks stands close to the railroad on the left. Beyond Nobel an excellent view may be had of the hilly portion of the city of Berkeley.

|

Berkeley. Elevation 8 feet. Population 40,434. Omaha 1,772 miles. |

West Berkeley station, also known as University Avenue, is in the older part of the city of Berkeley, and the center of the city is now almost 2-1/2 miles back toward the hills. Berkeley was named after Bishop Berkeley, the English prelate of the eighteenth century who wrote the stanza beginning "Westward the course of empire takes its way," by those who chose it as a site for the University of California. One of them, looking out over the bay and the Golden Gate, quoted the familiar line, and another suggested "Why not name it Berkeley?" and Berkeley it became.

The University of California was founded in 1868. It is one of the largest State universities in America, including besides the regular collegiate and postgraduate departments at Berkeley the Lick Observatory, on Mount Hamilton; colleges of law, dentistry, pharmacy, art, etc.,in San Francisco; the Scripps Institution for Biological Research, at La Jolla, near San Diego; and other laboratories for special studies elsewhere. It is a coeducational institution and had a total enrollment for 1914-15, not including that of the summer school, of 6,202. The members of the faculty and other officers of administration and instruction number 890. The university buildings at Berkeley are beautifully situated and have a broad outlook over San Francisco Bay. Their position can readily be identified from the train by the tall clock tower. Another prominent group of buildings occupying a similar site just south of the university grounds is that of the California School for the Deaf and the Blind.

Just before reaching Oakland (Sixteenth Street station) the train passes Shell Mound Park. The mound, which is about 250 feet long and 27 feet high, is on the shore of the bay close to the right-hand side of the track. It is composed of loose soil mixed with an immense number of shells of clams, oysters, abalones, and other shellfish gathered for food by the prehistoric inhabitants of the region and eaten on this spot. The discarded shells, gradually accumulating, built up the mound. Such relics of a prehistoric people are numerous about the bay, for over 400 shell mounds have been discovered within 30 miles of San Francisco. The mound just described is one of the largest, and from excavations in it a great number of crude stone, shell, and bone implements and ornaments have been obtained. The mounds evidently mark the sites of camps or villages that were inhabited during long periods, for the accumulation of such refuse could not have been very rapid. Archeologists who have studied the mound say that it must have been the site of an Indian village over a thousand years ago, and that it was probably inhabited almost continuously to about the time when the Spaniards first entered California.

|

Oakland. Elevation 12 feet. Population 150,174. Omaha 1,774 miles. |

The first stop in the city of Oakland is made at the Sixteenth Street station, about 1-1/2 miles from the business center of the city. Oakland is the seat of Alameda County and lies on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay directly opposite San Francisco. Its name is derived from the live oaks which originally covered the site. It is an important manufacturing center and has a fine harbor with 15 miles of water front. Visitors to Oakland should if possible take the electric cars to Piedmont, from which a fine view may be had of San Francisco, the bay, and the Golden Gate. This view is especially good at sunset. A walk or drive to Redwood Peak takes the visitor past the former home of Joaquin Miller, author of "Songs of the Sierras" and many other familiar poems, and affords equally fine views.

Leaving the station at Sixteenth Street, the train skirts the west side of the city and runs out on a pier or mole 1-1/2 miles long. This is the end of the "overland" part of the route, for the rest of the journey must be made on the San Francisco ferries. The distance across the bay is 4 miles, and the trip is made in the ferryboats in about 20 minutes. In crossing the bay the traveler sees Goat (or Yerba Buena), Alcatraz, and Angel islands to the right, Mann Peninsula beyond them, and the Golden Gate opening to the west of Alcatraz.

Goat Island lies close to the ferry course across the bay. Like most of the other islands in the bay, it is owned by the Government. On the nearest point there is a lighthouse station, and below it the rocky cliff is painted white to the water's edge. Just to the right of this is the supply station for the lighthouses of the whole coast from Seattle to San Diego. Behind this station is the United States naval training station, of which the officers' quarters may be seen on the hillside and the men's quarters near the larger buildings below. At the extreme northeast point of the island is a torpedo station, where torpedoes are stored for use in the coast defense.

On Alcatraz, the small island west of Goat Island, is a United States disciplinary barracks, and on Angel Island, north of Alcatraz, are barracks and other military buildings, a quarantine station, and an immigrant station.

Few people in viewing the Bay of San Francisco think of it in any other way than as a superb harbor or as a beautiful picture. Yet it has an interesting geologic story. The great depression in which it lies was once a valley formed by the subsidence of a block of the earth's crust—in other words, the valley originated by faulting. The uplifted blocks on each side of it have been so carved and worn by erosion that their blocklike form has long been lost. Erosion also has modified the original valley by supplying the streams with gravel and sand to be carried into it and there in part deposited. The mountains have been worn down and the valley has been partly filled. Possibly the valley at one time drained out to the south. However that may be, at a later stage in its history it drained to the west through a gorge now occupied by the Golden Gate. Subsidence of this part of the coast allowed the ocean water to flow through this gorge, transforming the river channel into a marine strait and the valley into a great bay. Goat Island and other islands in San Francisco Bay suggest partly submerged hills, and such in fact they are.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec35.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006