|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

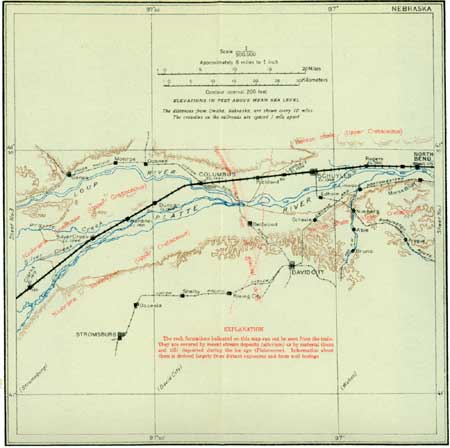

SHEET No. 2. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Schuyler. Elevation l,348 feet. Population 2,152. Omaha 75 miles. |

In the vicinity of Schuyler, the seat of Colfax County, little other than the cultivated fields on the alluvial plain can be seen from the train. The Dakota sandstone, which here lies a little below the surface (see fig. 3, p. 16), is of economic importance because of the artesian water it contains, and this water is held in confinement by the overlying shale. About 6 miles west of the town, between Lambert and Richland, the traveler passes from the Benton shale to the Niobrara limestone,2 although he would not suspect the change from anything he can see.

2The Niobrara limestone, so named because of its good exposures on Niobrara River in northeastern Nebraska, appears to extend across the eastern part of the State in a broad band under Tertiary and later deposits. It is exposed for 125 miles along the valley of Republican River, but to the north is seen only in Loup Valley near Genoa until Missouri and Niobrara rivers are reached, in Holt, Knox, Cedar, and Dixon counties, where it can be seen in large exposures. The material is mainly a soft limestone, chalk rock, or limy clay, presenting considerable variation in composition from place to place. The geologic age of this formation is shown in the table presented on p. 15. It is the youngest Cretaceous formation that is exposed near the Union Pacific Railroad in eastern Nebraska.

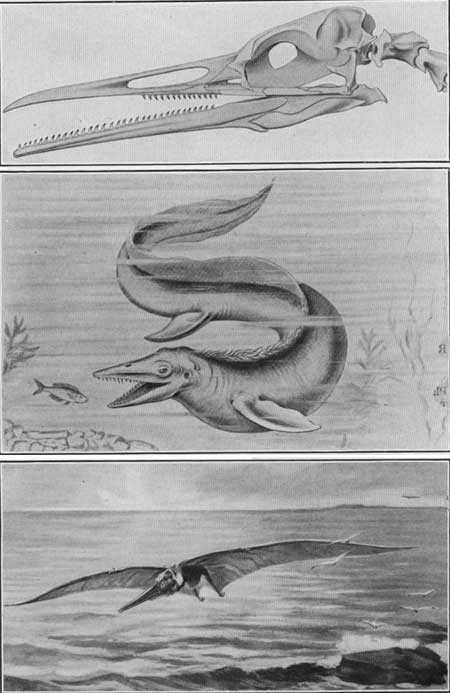

The westbound traveler is here passing directly toward the center of the ancient sea in which the sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous age were formed. He has crossed in the order of their deposition or age two formations of the Upper Cretaceous series—the Dakota sandstone and the Benton shale—and now enters upon the third, the Niobrara, which differs from the others in that it contains chalk similar to that of the well-known chalk cliffs of England. Some of the deep wells of this region encounter salt water in the shale and chalk rock. This is excluded from the wells by the casing, so that it does not mingle with the fresh water from the underlying Dakota sandstone. Other evidence of the former presence here of sea water are fossil shells of oysters and other animals that live in salt water and the bones of sea monsters such as Mosasaurus. (See Pl. V, B, and map on stub of sheet 2, p. 22.)

|

| PLATE V.—ANIMALS THAT LIVED IN CENTRAL NORTH AMERICA IN CRETACEOUS TIME. A (top), Skeleton of the head of Hesperornis. A large diving bird having teeth, which probably used in catching and holding fish on which it fed; B (middle), Restoration of a Mosasaur (Tylosaurus). A sea monster about 30 feet long. (After Hutchinson); C (bottom, Restoration of a Pterodactyl (Ornithostoma). A flying dragon measuring 18 feet from tip to tip of wings. (After Lucas.) |

A comparison of these ancient conditions with those of the present day indicates the slow, continuous change that is now and always has been in progress. Where the tourist now travels comfortably over a dry plain, these monsters sported in the water of the sea long ages ago. On the shores of this ancient sea lived equally strange beasts and birds of types that have long been extinct, and over its water sailed great flying dragons—the pterodactyls. The animals of that day were strikingly different from those of the present. The birds, unlike any now living, had jaws armed with teeth. The monarchs of the air then were not birds but flying reptiles, whose fore limbs had been modified into wings by the enormous elongation of fingers between which stretched thin membranes like the wings of a bat. (See Pl. V, C.) These flying dragons, some of which had a stretch of wing of 18 feet, were carnivorous; they were animated engines of destruction that somewhat forcibly suggest the modern war airplanes, of which they were in a sense the prototypes.

|

Columbus. Elevation 1,444 feet. Population 5,014. Omaha 91 miles. |

Columbus, the seat of Platte County, stands in the center of a fertile agricultural district. In 1864 it was a frontier town consisting of a few scattered shacks; but, with total disregard for things as they are and with true western confidence in things as they should be, George Francis Train, one of its citizens, then announced that Columbus was the geographic center of the United States and therefore the proper place for the national capital. Half a century has elapsed, however, and the seat of government is still at Washington.

Columbus is on Loup River, or Loup Fork, as it is usually called, near its junction with the Platte. The Loup is a stream of considerable volume and nearly constant flow, draining 13,540 square miles of the sand-hill region of northwestern Nebraska. West of the mouth of the Loup the Platte usually consists of small irregular streams among the sand bars, forming a lacework of small channels, whose pattern changes with every flood. Although the Platte is normally a large river, draining 56,900 square miles and having a maximum discharge near Columbus of 51,000 cubic feet a second, there is little or no water in it above the Loup during the dry season, the water being diverted for irrigation farther upstream.

Here and elsewhere in central and eastern Nebraska large quantities of grain are raised. Much of it, especially the corn, is fed to live stock. Animals raised on the western ranges are shipped here for fattening before they are sent to the market.

In the river bluffs along Platte Valley southeast of Columbus are the westernmost deposits made by the continental glaciers. East of a north-south line passing a little east of Columbus the superficial deposits consist of loess and of glacial till containing bowlders and fragments of rock brought from the north by the glaciers during one of their first southward advances in the Great Ice Age, some features of which are described below by W. C. Alden.1 These deposits make relatively high rolling plains. West of this line the surface of the plains is less uneven and slightly lower, and the superficial deposits consist of fragments of rock brought from the Rocky Mountains. These differ from the glacial drift in containing rounded pebbles, none of which bear evidence of glacial origin. They seem to have been brought from the mountains by streams which through long ages were engaged in leveling the Great Plains, much as Platte River is now grading its broad bottom lands, cutting away the higher places and building up the lower ones.

1Many of the physical features of eastern Nebraska were produced by sheets of ice that invaded the region during and after the earlier stages of the Great Ice Age. The deposit best exposed, in the street cuts and river bluffs in and near Omaha and along the line of the Union Pacific to the west, is a dustlike clay or loess. Beneath this lies the glacial drift.

Another feature is the great Missouri River, which swings majestically back and forth across its broad valley bottom as it gathers in the waters of the Great Plains on their way to the sea. In late Tertiary time, before the advent of the earliest continental ice sheet, Missouri River as now known was not in existence. The Dakotas were drained to Hudson Bay, and northeastern Nebraska was probably drained southeastward across Iowa. Platte River may have joined Grand River in Missouri. The bedrock east and west of the present lines of bluffs lies relatively low in the Omaha region, so that before the coming of the glaciers there was probably only a valley of moderate size with low slopes instead of bluffs.

The close of Tertiary time and the beginning of Quaternary time was marked in the northern part of the United States by the formation and spreading of vast sheets of ice similar to the great ice cap that now envelops all but the marginal parts of Greenland From the mild and equable climate of the Tertiary period there was a change, not necessarily sudden or violent—perhaps only the lowering of the average annual temperature a few degrees—so that a large part of the precipitation came in the form of snow, which was not all melted away in the summer. As this snow remained from season to season a vast amount finally accumulated and formed great glaciers. There were three main centers of accumulation and dispersion of this glacial ice, one on the Labrador Peninsula, a second west of Hudson Bay in the district of Keewatin, and a third in the mountains of western Canada. (See fig. 4, p. 22.)

FIGURE 4.—Map of North America showing the area covered by the Pleistocene ice sheet at its maximum extension and the three main centers of ice accumulation. At the opening of the glacial epoch the great Keewatin glacier spread southward and covered large parts of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Iowa and extended thence into eastern Nebraska, where it was probably several hundred feet thick. The dark-blue clay containing pebbles and small bowlders which is exposed near the base of the river bluffs in South Omaha and near Florence, several miles north of Omaha, is a part of the deposit made by this earliest ice sheet. It is known as pre-Kansan, sub-Aftonian, or Nebraskan glacial till. As the front of the great ice sheet invaded the Dakotas and Nebraska the eastward-flowing streams were blocked and their water was turned southward. This water must have formed a stream somewhere west of Omaha.

This first stage of glaciation was brought to a close by the melting of the ice in a warmer interglacial time or stage—the Aftonian. During this stage the streams of the region swept great quantities of sand and gravel down their valleys. Remnants of these sand and gravel deposits, deeply weathered and in places cemented to hard conglomerate by lime or iron oxide, overlie the pre-Kansan glacial till at several places in the river bluffs. A remarkable assemblage of animals invaded the region after the ice had disappeared, and the bones and teeth of many of these animals have been found in the Aftonian deposits of western Iowa. The late Prof. Samuel Calvin identified the remains of horses, camels, stags, elephants, mastodons, mammoths, and sloths. When these animals lived in western Iowa the climate there must have been comparatively mild and vegetation very abundant. Prof. Calvin says: "To supply these great herbivores with food required an abundance of vegetation such as could not be developed until some time after the pre-Kansan ice and all its climatic effects had disappeared from southwestern Iowa."

The character of the shells of the fresh water and land mollusks found in the Aftonian beds shows that the climate was similar to that of the present time.

After this mild stage the Keewatin glacier again spread southward and invaded the region. The ice reached at this stage its greatest extension in northern Missouri and northeastern Kansas, whence this is known as the Kansan stage of glaciation. As shown on the accompanying map (sheet 2) the western limit of the glacial drift crosses Platte River near Columbus, Nebr. The Kansan glacial drift that was uncovered in the cuts made in South Omaha for the Lane cut-off is bluish-gray clay containing red dish and purplish bowlders of quartzite, popularly known as "Sioux Falls granite," brought by the glacier from the ledges exposed near Sioux Falls, S. Dak. This drift is not now well exposed in these cuts, but it may be seen at a place 1-1/2 miles west of Papillion Creek, where it forms the lower 10 feet of the section exposed. Long exposure after the melting of the Kansan ice has changed the original blue-gray color of the upper part of this drift to rusty red, dissolved out the soluble calcareous ingredients for a depth of 8 feet, and caused many of the granitic pebbles to decay.

After the melting of the Kansan glacier the continental ice sheets did not again reach as far as the line of the Union Pacific Railroad. At the last or Wisconsin stage one lobe of the Keewatin glacier invaded north-central Iowa, extending to Des Moines, nearly as far south as the latitude of Omaha, and another lobe covered the northern and eastern parts of the Dakotas southward to a point about 90 miles north of Omaha, but Nebraska was not again invaded.

An interesting deposit overlying the glacial drift is exposed about 7-1/2 miles north of Omaha and at several places farther west. It consists of volcanic ash which must have accumulated after the melting of the Kansan glacier, at a time when the air was filled with volcanic dust from eruptions, possibly those of the Quaternary volcanoes of northeastern New Mexico.

West of Columbus the railroad is close to Platte River, whose bed is only a few feet below the track level. The flood plain is here 10 to 12 miles wide and is confined between bluffs 100 feet or more in height. It thus lies about 100 feet below the level of the Great Plains, which extend far to the north and to the south. The small towns of Duncan, Gardiner, Silver Creek, Clarks, and Thummel are passed before the next city is reached.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006