|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

WILLIAMS TO GRAND CANYON.

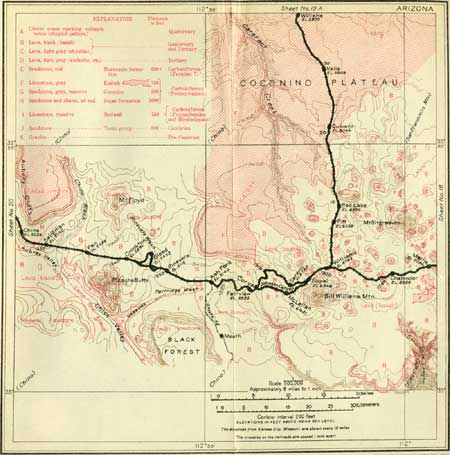

From Williams a branch of the Santa Fe Railway runs nearly due north 63.8 miles to the Grand Canyon. In the first part of its course this line passes over a rolling plateau of black lava (basalt) with numerous cinder cones on all sides. One notably large cone of bright red color is 7 miles north of Williams, and there is another one 10 miles north. Between mileposts 13 and 15 the Kaibab limestone, which underlies the lava, appears at the surface in several localities, but the irregular margin of the lava extends to milepost 18. From several points there are excellent views of Mount Sitgreaves to the east and Kendrick Peak to the northeast.

|

|

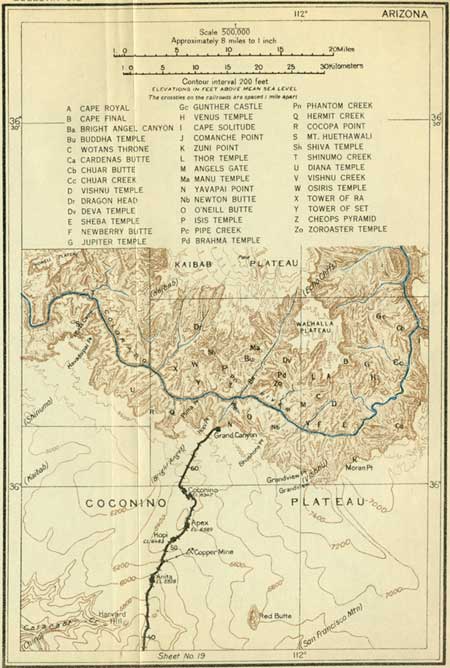

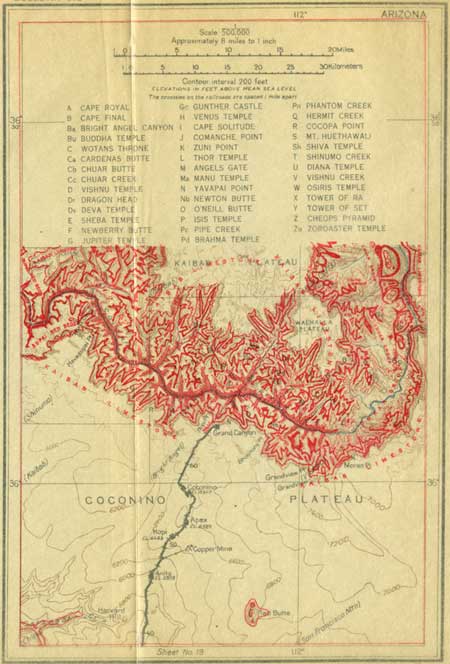

SHEET No. 19 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Beyond milepost 18 the entire surface is Kaibab limestone, which constitutes most of the great Arizona Plateau. This limestone rises gradually northward to the rim of the Grand Canyon and is trenched at intervals by small valleys opening westward and draining into Cataract Creek, a stream which flows into the Grand Canyon 60 miles to the northwest. In this region the plateau does not bear the pine forest which is so characteristic of it farther east, and even the junipers and piñons are widely scattered, much of the surface being covered by small brush. This change is due to diminished rainfall, for the other conditions are identical with those found farther east.

|

|

SHEET No. 19A (click on images for an enlargement in a new window) |

From points near milepost 40 (see sheet 19A, p. 130) Red Butte is a conspicuous feature, rising about 850 feet above the plateau a few miles east of the railway. As shown in figure 27, this butte is an isolated pile of gray and red shales, red sandstone, and conglomerate, protected by a 125-foot cap of black lava (basalt). The preservation of these beds in this butte is of great interest, for it shows that younger rocks formerly covered the Kaibab limestone of the plateau to a thickness of at least 800 feet. These rocks have been removed by erosion over the wide area extending to Sunset and Winslow on the east, and to the Vermilion Cliffs, far north of the Grand Canyon, as well as for an undetermined distance to the west and south. The small remnant remaining in Red Butte has been protected by hard basalt, probably a local outflow of lava of no great extent.

|

| FIGURE 27.—Section through Red Butte, near Grand Canyon, Ariz. |

By the presence of this outlier it is possible to recognize some of the geographic conditions existing at a time when the plateau was developed on the surface of higher strata than it is at present and when it may have been as extensive and as level as now. A few other outliers of these rocks overlying the Kaibab limestone at several points on the plateau help to show that originally the rocks of which they consist extended over a wide region south of the Grand Canyon.

Anita is a small siding from which considerable copper ore was shipped some years ago. The mines were 4 miles to the northeast. The copper ore occurs in irregular masses in the Kaibab limestone. It has been brought by underground solutions and deposited in part as a replacement of the limestone and in part in crevices and fissures in that rock.

At milepost 50, near Hopi siding, junipers and piñnons appear more abundantly, and toward the edge of the canyon they constitute a thick growth at most places and in parts of the region east of the railway make a forest of considerable extent. From Hopi northward ledges of Kaibab limestone become conspicuous. The beds dip to the south at a very low angle, which is hardly perceptible to the eye. Owing to this tilt in the beds, they rise toward the canyon and northward. The railway terminus is in a small depression a few rods south of the brink of the Grand Canyon.

|

Grand Canyon. Elevation 6,866 feet. Population 299.* Kansas City 1,363 miles. |

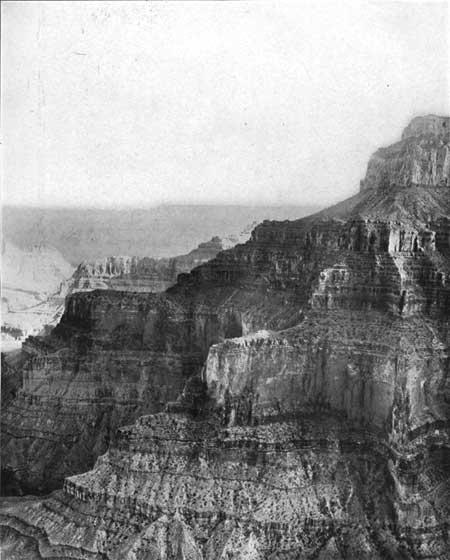

The hotels are built on the edge of a deep alcove that affords a superb view into the Grand Canyon and across it to the great Kaibab Plateau on the north side. Few persons can realize on a first view of the canyon that it is more than a mile deep and from 8 to 10 miles wide. The cliffs descending to its depths form a succession of huge steps, each 300 to 500 feet high, with steep rocky slopes between. The cliffs are the edges of hard beds of limestone or sandstone; the intervening slopes mark the outcrops of softer beds. This series of beds is more than 3,600 feet thick; and the beds lie nearly horizontal. Far down in the canyon is a broad shelf caused by the hard sandstone at the base of this series, deeply trenched by a narrow inner canyon cut a thousand feet or more into the underlying "granite." (See Pl. XXXIII, p. 127.) The rocks vary in color from white and buff to red and pale green. They present a marvelous variety of picturesque forms, mostly on a titanic scale, fashioned mainly by erosion by running water, the agent which has excavated the canyon.

The great river which has made its course in this deep canyon is the Colorado, one of the largest rivers of North America, which rises in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and Wyoming and empties into the Gulf of California. In the Grand Canyon it is a stream about 300 feet wide and 30 feet deep at mean stage and flows with a mean velocity of about 2 miles an hour; the discharge at this stage is 26,400 cubic feet a second. At flood stages, in May, June, or July, the depth may reach 100 feet, and the velocity and volume are greatly increased. In its course of 42 miles through the central part of the canyon the river falls about 500 feet, or 12 feet to the mile. The water contains much sediment, and in time of flood not only carries a large quantity of sand and clay but moves a considerable amount of rock downstream.1 Every rain fills the side canyons with rushing torrents, which carry into the river a heavy load of débris washed from the adjoining slopes. It has been by this means that the canyon was excavated, and the deepening and widening process is still in active operation. It began at the surface of the plateau and it will continue until the river reaches a grade so low that it can no longer move the débris; meanwhile the side streams will cut away the adjoining slopes and the canyon will widen until its sides become gentle slopes. Under present conditions this will require a million years or more.

1A very large amount of material is removed from the land and carried to the oceans by all rivers. Careful estimates based on analyses of river waters and measurements of volume of flow have shown that in a year the rivers of the United States carry to tidewater 513,000,000 tons of sediment in suspension and 270,000,000 tons of dissolved matter. The total of 788,000,000 tons represents more than 350,000,000 cubic yards of rocks, or a cube of about two-fifths of a mile.

|

Rocks. |

The formations exposed in the walls of the Grand Canyon are the rocks which underlie the Arizona Plateau, and most of them extend far beyond that province. The first 3,600 feet of beds, all of which lie nearly horizontal, are as follows:

Strata above granite, in walls of Grand Canyon

(beginning at brink of the canyon).

| Feet. | ||

| Limestone, light colored, partly cherty, mostly massive (Kaibab) | 700 | |

| Sandstone, light gray, massive, cross-bedded (Coconino) | 300 | |

| Sandstones and shales, all red (Supai formation) | 1,100 | |

| Limestone, light blue-gray, massive, surface mostly stained red (Redwall) | 550 | |

| Shale, with limestone and sandstone layers | Tonto group | 800 |

| Sandstone, hard, dirty gray to buff (on granite) | 150 | |

These formations are readily recognized by their color or character, as they are practically uniform in aspect and relative position from all points of view. (See Pl. XXXII, p. 126.) The top limestone, which caps the great plateaus on both sides of the canyon, has been removed in whole or in part from some of the promontories and buttes that project into the canyon; the Coconino, Supai, or Redwall beds have been removed from the lower-lying features. The outcropping edge of the Coconino sandstone2 is marked by a distinct band of light-gray rock all along the canyon walls 700 to 800 feet below the top. The red beds of Supai formation3 everywhere constitute the middle slopes of the canyon walls, usually presenting a great series of terrace-like steps of red sandstone. These steps are caused by the projection of harder layers of sandstone. The Redwall limestone4 forms a conspicuous cliff at the foot of the Supai slopes. The rock is hard and massive, and its resistance to erosion makes it a prominent feature in the canyon. Its surface is stained red by wash and drippings from the overlying red shales.

2This sandstone also caps many buttes such as Isis, Osiris, and Manu temples, the Supai formations everywhere and Angels Gate, as well as Buddha, Zoroaster, Brahma, Deva, and Vishnu temples and other similar features on which more or less of the overlying limestone remains.

3Such features as O'Neill Butte, Newton Butte, Tower of Set, Tower of Ra, Horus Temple, Rama Shrine, Lyell Butte, and Sagittarius Ridge consist of the Supai formation. It also is conspicuous in the slopes of many great ridges capped by higher beds, such as Shiva Temple, Wotan's Throne, Brahma Temple, Osiris Temple, Zoroaster Temple, and Vishnu Temple.

4The Redwall limestone projects in many flat-topped spurs and buttresses and constitutes outliers isolated by erosion, such as Cheops Temple, Newberry Butte, and Sheba Temple, which form striking topographic features.

|

| PLATE XXX—NORTH SIDE OF GRAND CANYON AS VIEWED BY TELESCOPE FROM EL TOVAR HOTEL. G, Granite and gneiss; U, sandstone, red shale, and limestone (Unkar); T, sandstone of Tonto Platform; Sh, shale of Tonto group lying directly of quartzite of Unkar; R, limestone (Redwall); S, red sandstone and shale (Supai); C, gray sandstone (Coconino); K, limestone (Kaibab). The Redwall butte in center is Cheops Pyramid. Beyond it are Buddha and Manu temples. The background is the Kaibab Plateau. |

|

| PLATE XXXI.—VIEW NORTHEASTWARD ACROSS THE GRAND CANYON FROM ZUNI POINT, EAST OF GRANDVIEW POINT. The lower slopes are red shales, limestones, sandstones, and lava of Unkar group, dipping east and overlain unconformably by Tonto sandstone and shales of Tonto group at T; R, Redwall limestone; S, red beds of Supai formation; C, gray sandstone (Coconino); K, Kaibab limestone. Painted Desert in the distance. |

The Redwall and the overlying Supai, Coconino, and Kaibab beds represent the greater part of the Carboniferous period. (See p. ii.) The Supai, Coconino, and Kaibab are of about the same age as the limestones along the Santa Fe line from Kansas City to Strong City, Kans., but there is a marked difference in their character.

The Tonto group, below the Redwall, consists of 800 feet of shales, largely of greenish color, and a basal sandstone averaging 150 feet in thickness. This group is very much older than the Redwall, and though at their contact the beds of the one are practically parallel to the beds of the other, there is a hiatus here which represents a very considerable portion of geologic time not represented by rocks in this region but recorded by many thousand feet of rocks in other portions of North America and in other countries. The shales make a long slope, interrupted by some subordinate ledges of limestone and sandstone, descending to a pronounced shell of the sandstone, called the Tonto Platform. This slope and the wide shelf at its foot are both very characteristic and easily recognized features extending along the lower slopes of the Grand Canyon.

For many miles this shelf of sandstone of the Tonto group is cut through by the steep inner gorge (shown in Pl. XXXIII, p. 127), which descends to the river, 800 to 1,000 feet below, and exposes the underlying granite and gneiss in very dark rugged ledges. These rocks are part of the old earth crust, which has been subjected to great heat and pressure. Later in its history its surface was worn down to a plane upon which were deposited thick beds of sand, clay, and other materials. In a wide area the basal sandstone of the Tonto lies directly on the smooth surface of this schist and granite, but in some places, notably in the broad part of the canyon northeast of Grandview, in Shinumo basin, in part of Bright Angel Canyon, in Ottoman and Hindu amphitheaters, and in the ridges extending northwest and southeast from a point near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek other rocks lie between the granite and the Tonto rocks. These are a succession known as Grand Canyon series, comprising the Unkar and Chuar groups, all named from localities in the canyon where they are well exposed. Their thickness is 12,000 feet or more and the beds dip at moderately steep angles. Their surface has also been worn off to a rolling plain, with many local hills on which lie the shales of the Tonto group. The Unkar group, which is the one exposed from most points of view, consists of a succession of basal conglomerates, dark limestone in thick beds, bright-red shales, heavy quartzites, and brown sandstones.1 This succession of rocks is plainly visible in Bright Angel Canyon and in the ridge culminating in Cheops Pyramid (see Pl. XXX), also in a wide area along the river in the region northeast of Grandview Point.

1These rocks have been named Hotauta conglomerate, Bass limestone, Hakatai shale, Shinumo quartzite, and Dox sandstone.

Many interesting features of the geologic history of the plateau region are recorded in the rocks of the Grand Canyon, and a summary of these records is given below.2

2The granite and gneiss at the bottom of the canyon are part of the oldest group of rocks constituting the earth's crust. The gneiss, which is the older, is in nearly vertical layers. It has been subjected to great heat and pressure, and into it the granite was forced in a molten state. Later the surface of these rocks was eroded to a plain by running water.

The next event of which there is evidence was the submergence of this plain and the deposition in water, of varying depth, of a thick series of sediments now represented by the 12,000 feet or more of sandstone, limestone, and shale constituting the Unkar and Chuar groups. These strata are believed to represent the Algonkian period (see p. ii), the earliest in which remains of life have been found. Several million years was required for the accumulation of these sediments. The materials of the limestone were laid down in the sea, those of the sandstone on beaches and along streams, and those of the shale mostly in estuaries.

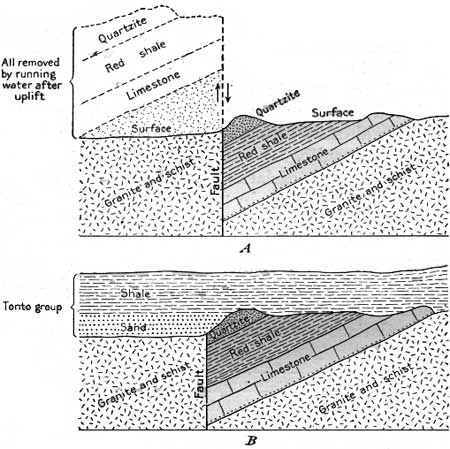

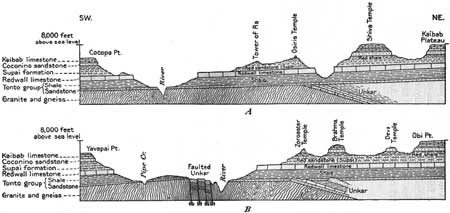

Next there was extensive uplifting of the earth's crust, with tilting and faulting of the rocks. Erosion then swept away a large amount of the Unkar and Chuar sediments, and over wide areas they were all removed. In figure 28 are shown some conditions of this sequence of events, as indicated by the relations of the rocks on the north side of the river opposite El Tovar.

FIGURE 28.—Ideal sections of faulted blocks of Unkar rocks in Grand Canyon, Ariz. A, Uplifted blocks that have been removed by erosion; B, rocks of Tonto group deposited on surface of Unkar group and granite. When the surface was reduced to a rolling plain with a few hills rising in places, there was another submergence by the sea, which deposited the sediments of the Tonto group. First the sand was deposited over the smooth granite surface (as shown by the heavy line in fig. 28, B). With deepening waters or diminishing force of the currents, the clay now represented by the shale of the Tonto group was laid down, soon burying the islands of Unkar and Chuar rocks and accumulating to a thickness of 800 feet or more. Remains of life in these rocks indicate that they represent a portion of later Cambrian time. The conditions in this region during the next three long and very important geologic periods are not known, for their representatives are absent except a small amount of the Devonian rocks found at one or two places. The sea may have laid down here, during those periods, deposits of great thickness, which were later uplifted into land areas, so that they were removed by streams and other agents of erosion.

In early Carboniferous time, the period characterized in other parts of the world by the accumulation of the older coal-bearing deposits, the entire region was submerged by the sea, which deposited calcium carbonate in nearly pure condition, now represented by 500 feet or more of the Redwall limestone. Much calcium is carried into the sea by streams, and its separation is effected by organisms of various kinds as well as by chemical reactions not connected with life. This deep submergence was succeeded by shallow water in which the red muds and sands now represented by the Supai formation were laid down to a thickness of a thousand foot or more. Where these sediments came from and the conditions under which they were deposited are not known, but undoubtedly they were derived from land surfaces not far away, where granites, limestones and other rocks were decomposing and yielding red muddy sediments to streams flowing out across the area of Supai deposition.

The change to the deposition of the Coconino beds was a very decided one, for the coarse gray Coconino sandstone usually lies directly on the soft red shale at the top of the Supai formation. The sand of which it is formed was laid down on beaches and in places where there were strong currents, for the grains are clean and light colored and the extensive cross-bedding (see Pl. XXIX, B, p. 119) indicates that there were vigorous currents in various directions. Such a deposit usually accumulates rapidly, so probably the 300 feet of sandstone represents a relatively short space of geologic time.

This epoch was terminated abruptly by deeper submergence due to a long, continued subsidence of the region, and in the extensive sea thus formed was laid down the thick deposit of calcium carbonate now represented by the Kaibab limestone. The numerous shells in this deposit are those of animals that lived in the sea. The water probably was moderately deep, and it is believed that the limy sediments accumulated very slowly during a long period of gradual subsidence. The time required for the accumulation of 700 feet of sediments of this sort must have been very great, surely several million years; it continued for a large part if not entirely through the later portion of the Carboniferous period.

Upon the Kaibab limestone, which constitutes the present surface of the high plateau, there were deposited many thousand feet of sandstones and other rocks through Permian, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic time. These rocks originally covered the present plateau area but were in greater part removed by erosion before the beginning of the excavation of the canyon. Remnants of them may be seen in Red Butte, not far south of El Tovar; in Cedar Mountain, far to the east on the Coconino Plateau; and in the great line of the Vermilion Cliffs, far to the north, beyond the Kaibab Plateau. Their removal required several million years, and most of it was completed before the excavation of the present canyon was begun.

|

| PLATE XXXII.—SOUTH WALL OF GRAND CANYON EAST OF GRANDVIEW POINT. View eastward. K, Kaibab limestone; C, base of gray sandstone (Coconino) on 1,100 feet of red shale and red sandstone (Supai) extending to top of Redwall limestone at D; R, top limestone of Tonto group. |

|

| PLATE XXXIII.—THE GRANITE GORGE IN THE GRAND CANYON, NORTHWEST OF GRANDVIEW POINT. Depth, 1,000 feet. Shelf of basal sandstone of Tonto group on sides; shale slopes above. R, limestone (Redwall); S, red sandstone (Supai). Shiva Temple in middle distance; Zoroaster Temple to right. |

|

Local features. |

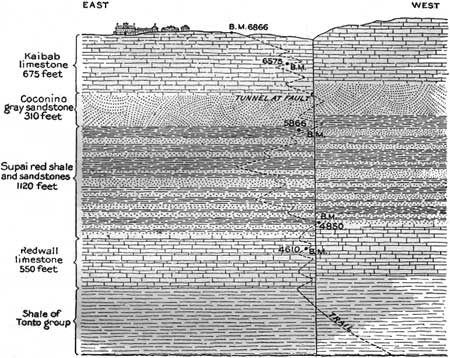

A fairly complete idea of the Grand Canyon can be obtained by observation for a few hours from the rim near the hotels. It is much more satisfactory, however, to go to Hopi and Yavapai points and down to the river, or at least to the Tonto Platform. A visit to Grandview Point (Pls. XXXI and XXXII) adds greatly to the completeness of the trip, and the Hermit trail is very interesting. The descent down the trails to the river is especially helpful in affording a sense of the scale of the canyon and giving opportunity to inspect the rocks at close range. There is neither difficulty nor danger in the journey. The Bright Angel trail descends at El Tovar by a great series of zigzags following the course of a very old Indian footpath. For the first 700 feet it goes down the irregular ledges of Kaibab limestone, the base of which is reached at the entrance to a small tunnel through which the trail passes. At this place there is a fault by which the rocks to the west are lifted 125 feet higher than they are to the east. The plane of this fault is at the entrance to the tunnel. The relations are shown in figure 29.

|

| FIGURE 29.—Section of rocks exposed on Bright Angel trail, Grand Canyon, Ariz., showing relations of fault, and the position of bench marks of the United States Geological Survey (brass caps with elevation above sea level). This fault and the pile of débris from the beds broken by it has made a trail practicable at this place, for generally the 300-foot cliff of Coconino sandstone is inaccessible. |

The character of this massive cross-bedded rock is well shown in the cliff just west of the fault. Next below are red shales and red sandstones of the Supai formation, 1,100 feet thick, extending to the top of a cliff of Redwall limestone, 550 feet thick, down which the trail winds in a tortuous course. Thence the trail goes down slopes of shale of the Tonto group to the Indian Gardens, where a spring has made an oasis formerly utilized by Indians. Not far beyond is the platform or broad terrace caused by the basal sandstone of the Tonto group making a wide shell through which the main gorge is cut 1,000 feet deep into the granite. (See Pl. XXXIII.) On the north side of the river is a great mass of dark sandstone, red shale, and limestone of the Unkar group, overlain by shale of the Tonto group farther back. These Unkar rocks are twisted and faulted but in general dip to the north at a moderate angle, as shown in figure 30 (p. 130).

|

| FIGURE 30.—Sections across Grand Canyon, Ariz., looking west. A, From Cocopa Point through Tower of Ra, Osiris and Shiva temples to Kaibab Plateau at Tyo Point; B, from Yavapai Point through Zoroaster, Brahma, and Deva temple to Kaibab Plateau at Obi Point. |

From Hopi and Yavapai points, which are within 2 miles of the hotels, there are superb views up and down the river, showing a great succession of cliffs, promontories, and buttes in endless variety of form, with geologic relations most clearly exhibited. They are all shown on sheet 19A (p. 130). The cross sections in figure 30 show the general features. From Grandview Point there is an extended view to the east and northeast, to the point where the canyon of the Little Colorado comes in. A wide area in the lower part of the canyon in this district is occupied by rocks of the Chuar and Unkar groups.

If the observer is impressed by the long time required for the excavation of the Grand Canyon in the slowly rising plateau, let him consider also the time required for the accumulation of the sediments in the many thousands of feet of rocks in the canyon walls. He may reflect also on their vast area, for they underlie not only the plateau he sees, but also a large part of our continent. An inch of the limestone required many years for its deposition, the shale was mud brought from distant hills by turbid streams and spread in thin layers, and the sands were deposited by streams or spread on beaches far from their original sources in the rocky ledges of the higher lands. It should be noted also that in the canyon section are lacking the rocks which represent a large part of geologic time in other regions. A very long time was also required for the deposition of 12,000 feet of the Unkar and Chuar groups and the planation of their surface and of the granite surface on which they lie. Probably this required as much time as is represented by the horizontal rocks in the upper and middle canyon slopes. Finally, a great period of time before all this is represented by the granites and associated rocks exposed in the inner gorge. They underlie the plateau and present a chapter in the earliest known history of the crust of our earth.

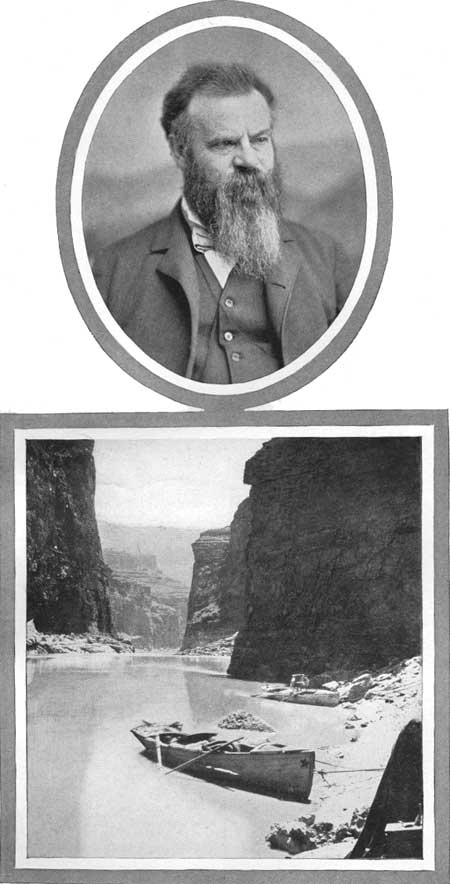

The first white men to see the Grand Canyon were Cárdenas and his 12 companions, who were guided there by Hopi Indians from Tusayan. Cárdenas was sent by Coronado to find the wonderful river of which DeTovar had heard from the Indians. He remained four days on the rim at some point now unknown, looking in vain for a way to descend. It is always interesting to recall the heroic trip made by Maj. J. W. Powell down the Grand Canyon in small boats when practically nothing was known of its course or character. His journey began at Green River, Wyo., May 24, 1869, and was notably successful. A portrait of Maj. Powell and a view of his boats are given in Plate XXXIV (p. 128).

|

| PLATE XXXIV.—MAJOR J. W. POWELL AND THE BOATS IN WHICH HE MADE THE TRIP DOWN THE GRAND CANYON. The view is in Marble Canyon. |

The hotel at Grand Canyon was named for Pedro de Tovar, who was ensign general of Coronado's expedition. He and most of his associates were men of high social position, De Tovar's father being the guardian and lord high steward of Doña Juana, the daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who married Philip the Second. On no other exploration were there so many distinguished men as accompanied Coronado on his dangerous journey from Mexico into this unknown land.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec19a.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006