|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Ludlow. Elevation 1,779 feet. Population 255.* Kansas City 1,614 miles. |

The Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad runs north from Ludlow (see sheet 23, p. 162) to Goldfield, Nev., noted for its rich gold mines, and a small branch road goes south 10 miles to the Bagdad-Roosevelt mine. Ludlow is in the south end of another basin, which extends far to the north. For a long time this basin has been receiving the drainage of a wide area of surrounding hills, so that the thick deposit of silt and sand which it contains includes evaporation products as well. A deep boring (1,500 feet) at Ludlow and another (600 feet) 8 miles to the north penetrated many sand beds containing water, but all the water carried so much salt that it could not be utilized. The water for town and railway consumption is brought from the spring at Newberry by a daily train of tank cars. A short distance south of Ludlow are buttes and ridges of volcanic agglomerate and tuff containing sheets and intruded masses of light-colored lava (rhyolite).1

1Nine miles south, at the Bagdad-Roosevelt mine, there are ridges of older igneous rocks (mainly monzonite porphyry and latite). A sheet of breccia of considerable extent at this place carries gold and also in places rich copper ores, which have been extensively mined. This ore-bearing breccia is a rhyolite porphyry crushed into fragments and cemented together by silica. Its relations are clearly exposed in outcrops and some of the shallower workings. Northwest of Ludlow there is a high rugged range known as the Cady Mountains, consisting of bright-colored volcanic tuffs and lavas (rhyolite), in large part of green, brown, and buff tints. This series also constitutes the hills and ridges northeast of Ludlow, but farther north, near Broadwell station on the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, high ranges of light-colored granite stand on both sides of the basin. Thirteen miles northeast of Ludlow volcanic tuffs capped by black lava (basalt) are exposed, abutting against granite in the slope of the higher ridge on the north.

|

|

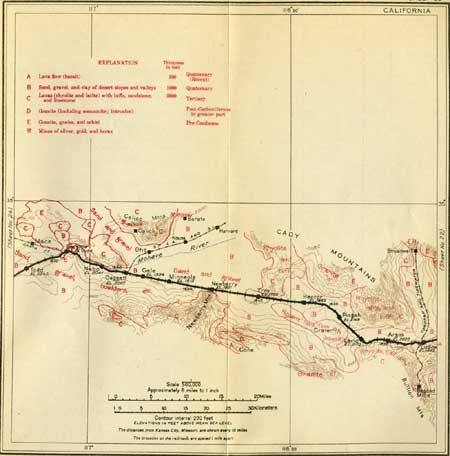

SHEET No. 23 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The bottom of the basin a few miles north of Ludlow usually presents a vast expanse of glistening, mud-cracked surface, but sometimes it is covered by water. This bare plain is in conspicuous contrast to the general area of the desert, which is covered with the creosote bush (Covillea tridentata).

Ludlow is the outlet for the Death Valley borax, now carried by rail but formerly by the well-advertised 20-mule team. One of the wagons used in this transportation is now on exhibition on the north side of the track a few rods beyond the station. Its capacity is 10 tons.

West of Ludlow the train climbs rapidly along the slopes of buttes of volcanic rocks (rhyolite and tuff), which rise to considerable height in a series of ridges extending far to the south. These rocks are well exposed at Argos siding, 5 miles west of Ludlow.

At a point 1.4 miles west of Argos, just beyond milepost 700, the train crosses a low divide and enters another basin. The bottom of the basin is largely occupied by a very recent sheet of lava,1 the edge of which is half a mile beyond milepost 701. The railway skirts the northern edge of this lava flow for 6 miles, or to a point a short distance beyond Pisgah siding. Near the center of the flow, about 2 miles southeast of Pisgah siding, rises a beautifully symmetrical cinder cone about 250 feet high, with a large, deep crater in its summit. This cone, which is usually called Mount Pisgah, is as fine an example of a recent volcanic outflow as can be seen anywhere. Some of its features are shown in Plate XL (p. 151).

1The lava is black and cellular, and although the sheet is not very thick it presents a surface of extreme irregularity, closely resembling some of the most recent flows in other portions of the world.

As in the other recent flows, the lava welled out of an irregular orifice and spread widely over the bottom of the basin. As its area widened the surface congealed, but the hot lava broke out from underneath, causing tunnels and irregular caved-in areas which are typical. That the molten lava was filled with steam is shown by the scoriaceous or honeycombed character of the rock. Many of the details of flow are clearly shown by the surfaces, which in some places are ropy, as the lava puckered in congealing, and in others are glassy and smooth, like slag from a blast furnace. Many of the tunnels are extensive, and there are also innumerable huge bubbles or blisters, more or less cracked by deep fissures due to the contraction caused by cooling. The margin of the flow presents an irregular edge of low cliffs, in most places consisting of great masses of broken fragments, formed as the congealing rock was pushed along by the advance of the flow.

The cinder cone was built up at the end of the eruption and undoubtedly marks the place of the orifice. In its last stages the action was mainly a violent escape of steam, which blew out a large amount of cindery or pumiceous material, together with occasional hardened masses of lava. This was all thrown to a considerable height in the air, and, falling on all sides, quickly built up a cone. A mass of cinder lying against the west inner side of the cone is slightly different in color, and probably is the product of a final supplemental outburst.

The recent date of this cone is indicated by the fact that the pile of loose material has not been affected by the powerful erosive processes of the region, and there is no perceptible oxidation of the rocks or cinders. The lava still shows the jagged edges due to accidents of flow, and there are many minute stalactites of lava hanging in the roofs of the tunnels. The material also overlies and abuts against sand deposits that are of recent age.

|

| PLATE XL.—MOUNT PISGAH, BETWEEN LUDLOW AND BARSTOW, CAL. A recent cinder cone and its great lava sheet. View southward from a point near Santa Fe Railway. Note broken blisters and caverns in lava and the ropy surface of lava in top foreground. |

The mountains which rim the basin north and south of Pisgah siding consist mostly of granites, the thick mass of volcanic tuffs and lavas constituting the southeast end of the Cady Mountains northwest of Ludlow apparently having ended at a point northeast of Pisgah. From Pisgah to Troy, a distance of 12 miles, there is a down grade of 368 feet into the basin.

North and south of Hector there are low hills of Tertiary volcanic tuff. The western extension of the lava sheet from Mount Pisgah lies some distance south of Hector, but it is approached and crossed by the railway between Hector and Troy.

At Troy siding the basin opens out westward into a broad flat that extends to Mohave River, about 7 miles to the north. The plain here is remarkably smooth, and it is covered in part by silt and in part by low sand dunes. In an area of considerable extent about Troy there is a large volume of fairly good water only a short distance below the surface, and it rises within 4 feet of the surface near the siding. On account of this supply a number of settlers have recently taken homesteads in this flat, expecting to pump the water for irrigation. At most places here the water does not carry very much salty material, for this part of the valley drains into Mohave River, and salts appear not to have accumulated in it.

A short distance northeast of Troy is a range of low hills consisting of volcanic tuff and lavas (rhyolite and basalt), which bear off northwestward to Mohave River. These materials probably also underlie the flat, for they appear in a number of low knobs to the west, south, and southeast of Troy. The larger mountain mass, 5 miles south of Troy, however, consists of light-colored granite (quartz monzomte). A very thick deposit of bowlders and gravel lies against these granite slopes, constituting high hills of rounded form. In one area of considerable extent these gravel beds are surmounted by a flow of black lava (basalt),1 which caps a high mesa clearly discernible south-southwest of Troy.

1This lava came from a cinder cone at high altitude behind the main granite range and flowed to the north and northwest down a valley of moderately steep slope. Its irregular termination 4 miles southwest of Troy is not very high above the level of the railway. A portion of the northern rim of this old valley in the higher slopes 6 miles south-southwest of Troy has since been cut away by erosion, so that part of the black edge of the upper portion of the flow is now visible from Troy.

|

Newberry. Elevation 1,831 feet. Kansas City 1,647 miles. |

Newberry siding, 6 miles west of Troy, is notable for the great spring which issues from the volcanic tuff at the foot of the mountain a short distance southwest of the station. The water is piped to the station, pumped into tanks, and used for railway and residents as far east as Bagdad, an interval in which no good local water is obtainable. For this service the operation of a daily train of 20 tank cars, holding 10,000 gallons each, is required. This spring is supplied by rain water which sinks underground in crevices on the mountain slope and finally accumulates in some main joint plane which extends to an outlet at the foot of the range.

North of Newberry is a wide flat extending to Mohave River, the course of which is indicated by a line of mesquite trees plainly in view from the train. These trees are always indicative of the proximity of water, although in some localities the supply is deep underground and in but small volume. They occur in considerable numbers about the spring at Newberry and on the flat near Troy, where the water is so near the surface. To the south is Newberry Mountain, a prominent steep ridge showing a thick succession of volcanic rocks (tuff, breccia, and rhyolite) dipping at a moderate angle to the southwest. These beds are probably the "Rosamond series," a formation characteristic of the borders of the Mohave Desert.

The Mohave Desert is a large quadrangular area of arid land lying north of the San Gabriel Mountains and southeast of the Sierra Nevada. Its eastern limits have not been exactly defined. The railway runs close to the southeast border of this desert between Barstow and Summit.

From Newberry to Daggett the country is nearly level, for the train traverses the broad river plain and gradually approaches Mohave River, which is but a short distance north of Daggett station.

|

Daggett. Elevation 2,007 feet. Kansas City 1,658 miles. |

The village of Daggett serves as a source of supplies for numerous mines and a few ranches scattered along the valley. Here trains of the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, coming from the northeast, pass upon the Santa Fe tracks, which they use to Colton. Two miles north of Daggett the Calico Mountains, so named because of the bright variegated color of their slopes, rise abruptly from the north margin of Mohave Valley. They consist of a thick succession of beds of ash and other fragmentary materials thrown out of volcanoes and sheets of light-colored lava (rhyolite), dipping at a moderately steep angle to the east. On the south slope is the Calico mine, which has been a large producer of silver. On the east side of the Calico Mountains the volcanic series includes clays containing colemanite,1 a crystalline borate of lime. These clays have been mined extensively for the production of borax. For many years large amounts of this material were treated at a refinery in Daggett, but the working of deposits of purer mineral in other areas has forced this refinery to cease operations. The "borax mines" are not visible from the railway except possibly by a very distant view to the northwest from Newberry.

1Colemanite contains 50.9 per cent of boric acid, 27.2 per cent of lime, and 21.9 per cent of water. The deposits near Daggett are believed to have been formed by replacement of limy beds that were laid down locally during the evaporation of lake waters of Tertiary time, in intervals between some of the great outbursts of volcanic ejecta, which formed so large apart of the Tertiary deposits. The boric acid was undoubtedly derived from fresh volcanic materials and carried to its present position by underground waters. The deposits are in two principal beds, each 5 feet thick and about 50 feet apart. These beds dip steeply and have been mined to a depth of 500 feet. All the borax produced in the United States is obtained from California mines, mainly from Lang, north of Los Angeles and Death Valley. The value of borate ores in 1913 is estimated at nearly $1,500,000. The borax is produced by heating the pulverized colemanite with a solution of sodium carbonate, forming the soluble sodium borate, which crystallizes.

South of Daggett is a broad range of rounded hills which rise steeply from the valley. Canyons among them reveal thick deposits of gravel and sand, in part cemented into conglomerate. Beds of volcanic tuff and ash are also included in these deposits.2

2At the base of this series is a coarse breccia which, in the canyon 6 miles south of Daggett, is underlain by granite. It contains large fragments of various igneous rocks and also of the underlying granite. Farther southeast it includes many fragments and bowlders of dark fine-grained rock (basalt), evidently derived from Ord Mountain, a high ridge 14 miles southeast of Daggett. In the northwestern slope of this mountain there are mines of copper ore carrying gold.

From Daggett to Barstow the train ascends the valley of Mohave River along its south side and in places follows the bank of that stream. For much of the year the water does not flow as far down as Daggett, but sometimes after a heavy rainfall the river bed is filled from bank to bank. The Mohave is one of the largest of the so-called lost rivers of the desert provinces. It rises on the north slope of the San Bernardino Range, flows northward for about 50 miles, to Barstow, and then, east of Daggett, turns eastward into a stretch where it ceases to flow except at times of high flood, when it ultimately reaches Soda Lake, or the sink of the Mohave, just south of the Amargosa drainage basin. Mohave River is in sight of the railway all the way from a point near Newberry to a point south of Victorville.

Near milepost 745, about 4 miles west of Nebo siding, the river valley is narrowed by high buttes of reddish lava (rhyolite) and other rocks, and bends considerably to the north around a ridge projecting from the south. Recently a deep cut, a mile in length, has been excavated through this ridge for the railway. The principal materials exposed in this cut are gravels and sands deposited by Mohave River a long tune ago. In the central part of the cut a red lava (rhyolite) is reached, and the gravels and sands are exposed abutting against slopes of the lava, which rises to the surface in prominent buttes not far north and also constitutes several small knobs along the river bank from this place to Barstow.1

1The sedimentary rocks of this region comprise about 3,000 feet of beds of middle Tertiary age. They lie on a somewhat irregular surface of granite and gneiss and are very much flexed and faulted. Three general divisions are recognized. The lowest, 1,200 feet or more thick, is mostly fine tuff and volcanic ash, with thin lava flows and at the base some sandstones, in large part conglomeratic. It weathers into irregular hills in which brown, gray, greenish-yellow, and purplish shades prevail. The middle division, 1,500 feet or more thick, is made up of pale-greenish clay, with thin beds of sandstone, ash, and limestone, and at the base a deposit of coarse granite fragments in places cemented into breccia. The top division consists of loose beds of angular rocks, fine gray ashy sand, and clay, forming round buff-colored hills. It contains abundant fossil bones of extinct species of horses, camels, and other mammals believed to be of later Miocene age, some of them the same as the bones found in the Santa Fe marl. The Tertiary rocks cropping out along the north side of Mohave River from Daggett to Barstow are fine sands and clays, with thin interstratified limestones and volcanic rocks. A dark rocky ridge of tuff and volcanic flows comes to the river a short distance west of Daggett. The rocks in the knobs immediately about Barstow are rhyolite, but clay and limestone appear not far north and granite and schist crop out to the northwest and to the northeast.

|

Barstow. Elevation 2,106 feet. Population 1,066.* Kansas City 1,668 miles. |

Barstow owes its existence mainly to railway and mining trade. It is a railway division point where the line to San Francisco, by way of Bakersfield, diverges from the line to San Bernardino, Los Angeles, and San Diego. A spacious hotel is located here under the title of Casa del Desierto (house of the desert). The valley of Mohave River is narrow at Barstow. There are two prominent buttes of red lava (rhyolite) in the southern part of the town, and ridges consisting of volcanic tuff interstratified with sheets of lava rise a short distance north of the river. A small but very prominent butte of red lava (rhyolite) stands in the center of the valley just north of Barstow station.

The railway, which has run north of west for 100 miles beyond Cadiz, here turns southward toward Cajon Pass and San Bernardino. After leaving Barstow2 the train continues to follow the south or east bank of Mohave River past Todd, Hicks, Wild, Helen, and Bryman to Oro Grande and beyond. The low flat along the stream is not wide, but most of it is utilized for irrigation at numerous ranches. The long slopes adjoining the river flat consist of gravels and sands apparently underlain at no great depth by volcanic rocks.

2Mileposts to Los Angeles indicate the distance from Barstow.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec23.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006