|

Geological Survey Bulletin 614

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part D. The Shasta Route and Coast Line |

ITINERARY

|

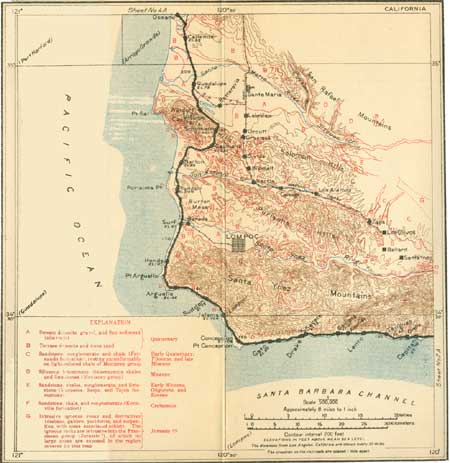

| SHEET No. 3A (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Orella. Los Angeles 126 miles. |

Naples and Capitan (see sheet 3A, p. 114) are small places beyond Elwood. From Orella (o-rail'ya), the next station, to Gaviota (ga-vyo'ta, Spanish for sea gull) and a little beyond the Monterey shale beds along the coast are very uniform, having a southerly dip of 30° to 45°. They are well exposed along the foot of the sea cliff at low tide. The straight shore line along this part of the coast is due to the uniform trend or strike of the beds and their steep seaward inclination or dip, which render them very resistant to the attack of the waves. Nevertheless, at a number of places between Tajiguas (ta-hee'gwas), 346 miles from San Francisco, and Honda (ohn'da, Spanish for deep), 310 miles, the railroad company has been compelled to build a sea wall of concrete.

At several points the low terrace which the railroad follows is covered by bowlders from the hills immediately to the north. In the vicinity of Gaviota these hills come close to the shore, and a good view may be had of the coarse, steeply inclined sandstones.

|

Alcatraz. Los Angeles 134 miles. Gaviota. Elevation 92 feet. Los Angeles 135 miles. |

At Alcatraz (Spanish-American pronunciation al-ca-trahss', meaning pelican), on the right (north), there is an oil refinery to which oil is piped across the Santa Ynez Mountains from the Santa Maria field.

From Gaviota nearly to Point Conception the rocks dip south, but at El Cojo (co'ho, Spanish for cripple), 11 miles beyond Gaviota, the shale beds dip north, indicating some complications of structure at the pronounced bend in the coast which forms Point Conception. The shale extends northwestward from Point Conception to Surf (Lompoc Junction).

|

Concepcion. Elevation 106 feet. Los Angeles 150 miles. |

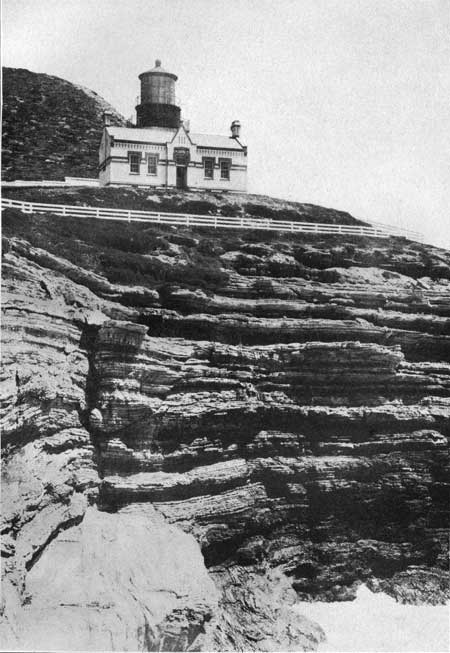

The wind-swept country near Point Conception is devoted to the raising of cattle and hay. On the point are a lighthouse (Pl. XXVIII, p. 118) and a life-saving station. From the train in passing from Carpinteria to Concepcion, a distance of 56 miles, beautiful views are obtained of the Santa Barbara Islands. The intervening Santa Barbara Channel is shallow and, with the islands, belongs to the continent rather than the ocean. Beyond the islands the depth of water increases very rapidly, and this steep submarine slope, which on land would appear as a large cliff, marks the real boundary between continent and ocean. This slope has probably been formed by faulting as the continent rose. It runs north and south off Point Conception and determines the abrupt change in the trend of the coast.

|

|

PLATE XXVIII—LIGHTHOUSE AT POINT CONCEPTION, CAL. Built on cliff of remakably uniform thin-bedded Miocene shale (Monterey). |

At milepost 320 the train crosses Jalama (ha-lah'ma) Creek. On the left, near the creek, is the house of an early Spanish settler who harbored the 200 survivors of the Yankee Blade, wrecked on this coast in 1856. The anchor of the Yankee Blade may be seen on the left (at milepost 318), in the field, just after the train emerges from a small tunnel a mile southeast of Sudden.

|

Sudden. Elevation 75 feet. Los Angeles 158 miles. |

Very good exposures of Monterey shale are to be seen near Sudden, where cracks in the siliceous shales are filled with hardened asphaltum. The lighthouse at Point Arguello is built on contorted Monterey shale, here very well exposed. The terrace which the railroad follows is narrow but well defined, and slopes gently toward the foot of the hills. At some points in the region between Sudden and Point Arguello there are indications of an older, higher terrace. Near Point Pedernales (pay-dair-nah'lace, Spanish for flints) the railroad crosses Canada Honda (ca-nyah'da ohn'da) Creek, near the mouth of which, within plain view, is the wreck of the Santa Rosa, blown ashore in 1911.

From Point Pedernales, which marks the western extremity of the Santa Ynez Mountains, northward the country near the coast is covered with sand dunes which have drifted from the beach over the terraces and lower hill slopes, impelled by the strong winds which continually prevail in this region. The drifting sand sometimes covers the railroad track and delays traffic. To prevent this the Southern Pacific Co. is planting successfully acacia trees (Acacia latifolia) and a coarse, stout beach grass (Ammophila arenaria) that is used on the dikes in Holland.

About 5 miles southeast of Point Pedernales is a mountain called El Tranquillon (tran-keel-yohn', Spanish for maslin, a mixture of wheat and rye). The reason for the application of this name to the mountain is unknown. Two or three areas of Franciscan (Jurassic?) rocks are exposed just north of El Tranquillon, indicating that this formation is the core of the main Santa Ynez uplift.

The hills northeast of Point Pedernales to an elevation of over 1,000 feet are covered by old terrace and sand-dune deposits.

|

Lompoc Junction. Elevation 47 feet. Los Angeles 172 miles. |

Surf (Lompoc Junction), at the mouth of Santa Ynez River, is well named from the breakers that tumble on its broad beach—Lompoc Beach. Here the Monterey shale appears again, dipping to the south at a rather low angle. Lompoc Beach is a "gold beach" that renews its riches every few years, and occasionally it is the scene of beach placer mining. The strong waves due to the winter storms strike the Lompoc Beach between Honda and Purisima Point at a low angle and cause the sand to drift northward. The sand made up of lighter minerals drifts most rapidly, and thus leaves behind along this beach the black sand of dark, heavy minerals. The black sand contains some gold, and when the sand is long exposed to the concentrating wave action it may become rich enough to pay for washing, but the gold content is not large, the beach placers here being not so rich as those of the coast of northern California and southern Oregon.

From Lompoc Junction a branch railroad ascends the Santa Ynez Valley for 10 miles to the town of Lompoc. The climate and soil in this vicinity are particularly adapted to seed growing, and great quantities of beans and sweet peas are raised here for seed. Much of the mustard produced in the United States comes from Lompoc. The largest industry of the place, however, is the mining and milling of diatomaceous earth, of which there are large deposits in Miocene shale (Monterey) a few miles to the south. Thousands of tons of white limestone are also shipped from Lompoc annually.

Northeast of Lompoc Junction is Burton Mesa, part of an unusually broad and even marine terrace. For about 12 miles north of Lompoc Junction to Schumann Canyon the railroad passes through a region of sand dunes. These rest on a terrace cut in Monterey shale, which just south of Tangair is hard, white, and porcelaneous. At many places the hard layers of the shale are full of minute cracks which contain hardened asphaltum. At other places oil seeps from the shale.

About 10 miles east-northeast of Lompoc Junction is the Lompoc or Purisima oil field, the wells of which are from 2,000 to 4,000 feet in depth and produce from 25 to 400 or 500 barrels each daily.1

1The Santa Maria oil district lies in northern Santa Barbara County, in the region of rolling hills between the Santa Ynez and San Rafael mountains. The district comprises three principal fields—the Santa Maria or Orcutt field, the Lompoc field, and the Cat Canyon field. Up to the present time the greater part of the development has taken place in the Orcutt field, as this was the first one discovered and exploited. The first successful well was finished in August, 1901. The wells in this field yield from 60 to 2,500 barrels of oil a day each, although initial yields of 2,000 to 12,000 barrels have been recorded. The gravity of the oil is from 18° to 31° Baumé. The wells of the Lompoc field yield oil of 16° to 37° Baumé. Successful wells were drilled in this field in 1904, and since that time the further development of this part of the district has been assured. In the Cat Canyon field the wells so far brought in have yielded from 150 to as high as 10,000 barrels a day. The oil in this field runs from 11° to 19° Baumé.

The Pacific Coast Railway connects the different fields with Santa Maria, Port San Luis, and San Luis Obispo, the last named on the Southern Pacific Coast Line. The greater quantity of the oil produced is piped to the refineries at Gaviota and Avila, on the coast; the Associated Oil Co. owns the former and the Union Oil Co. the latter plant. The Standard Oil Co., which controls a small part of the output, has a pipe line connecting the district with Port San Luis.

The shales of the Monterey group are the probable source of the oil in the district and the present reservoir in some of the fields and are characterized by their diatomaceous composition.

The Fernando formation, a series of sandstone, conglomerate, and shale, rests unconformably upon the Monterey and derives its chief importance in connection with studies of this oil district from the facts that it obscures the oil-bearing formation over a wide area, that it affords through its structure a clue to the structure of the underlying Monterey, and that it acts as a reservoir for the oil in the Cat Canyon field and as a receptacle for escaping bituminous material in several localities within the district.

This district is a region of long sinuous folds, a peculiar type of structure characteristic of the Santa Maria region. It is near the axis of these folds that the productive wells are located.

In 1913 there were 289 producing wells and the output was 4,938,185 barrels. The annual output of the district varied from 99,288 barrels in 1902 to 8,651,172 barrels in 1907. The total output of the Santa Maria district from 1902 to 1913, inclusive, was 56,599,642 barrels.

This district yields four distinct grades of petroleum in addition to the heavy oil which flows from springs or collects as asphalt deposits. These petroleums vary widely in physical and chemical properties and as a consequence are utilized in many different ways, the lighter oils usually for refining and the heavier for fuels, road dressing, etc. The oil as it comes from the wells contains varying quantities of gas, often amounting to a considerable percentage. Some of this gas is very rich in gasoline hydrocarbons, which are removed before utilizing for fuel. The greater portion of the oil is refined at Port San Luis and Gaviota, from which it is distributed by means of tank steamers.

|

Tangair. Elevation 210 feet. Los Angeles 178 miles. |

Near milepost 298, just south of Tangair, there is a cut affording fine exposures of the siliceous Monterey shale. Here the railroad attains the summit of Burton Mesa, whose surface has been cut by wave action across the tilted Monterey beds. There is an extended view over it on the right.

|

Casmalia. Elevation 281 feet. Los Angeles 187 miles. |

Beyond Schumann Canyon and Casmalia the formation exposed is the Monterey shale, which is much folded. About Casmalia considerable barley is grown for hay and grain. The rounded hills in this vicinity are golden in August with the bright little flowers of the tarweed.

North of Casmalia the railroad crosses a well-defined anticline. Several oil wells seen on the left (west) side of the track have been drilled on the south flank of this fold and obtained commercial quantities of very heavy oil at depths ranging from 1,800 to 2,500 feet.

|

Schumann. Elevation 401 feet. Los Angeles 190 miles. |

At Schumann station, which lies on the north flank of the anticline, the Monterey shale is soft and thoroughly impregnated with oil, which colors it dark and trickles from it in places. This is as good an exposure of the soft upper beds of the Monterey as can be seen along the railroad. The lower portion of this shale formation is hard, thin bedded, and siliceous, but the upper portion is softer and does not show the bedding as plainly.

Beyond Schumann the railroad swings to the left, and the broad valley of Santa Maria River may be seen on the right. The train passes along the northeastern base of the Casmalia Hills, where the rocks exposed in most of the cuts are of Pleistocene age, although the Fernando formation occurs in the hills a short distance south of the track. Several old asphalt mines may be noticed in this vicinity. The asphalt occurs in the form of dikes and irregular lenses in the soft Fernando sandstones.

On the right (east) side of the track, about 2 miles south of Guadalupe (gwa-da-loo'pay) is Guadalupe Lake, the water of which has been impounded by drifting sands. Beyond the lake, at Betteravia is a beet-sugar factory.

|

Guadalupe. Elevation 79 feet. Population 480.* Los Angeles 198 miles. |

The rich alluvial valley about Guadalupe produces large crops of beets, potatoes and barley. The main Santa Maria Valley, which extends eastward from Guadalupe for 10 or 12 miles, is primarily a structural valley that has been deeply filled with Pleistocene and alluvial deposits. A clearly defined terrace follows the north bank of Santa Maria River, and northeast of the valley are the San Rafael Mountains. The lower slopes are marked by an anticlinal fold, in the heart of which is a large mass of serpentine and Franciscan rocks. The flanks of this fold, including the larger part of the southwestern slope of the mountains, consist of distorted Monterey shale.

Just north of the Guadalupe station the railroad crosses Santa Maria River, the boundary line between Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties. Looking southeast from this bridge the traveler can see Graciosa Ridge, with the wells of the Orcutt or old Santa Maria oil field in view on its flanks. Mount Solomon, a flat-topped, buttelike peak, composed of Tertiary rocks, is visible just to the left (east) of the oil field. It is the culminating point of Graciosa Ridge. Southwest of the Santa Maria bridge the drifting sands encroach to an elevation of 1,000 feet on the flanks of Sulphur Ridge. This encroaching sand rising so high on the mountains is one of the peculiar characteristics of this part of the coast.

For 14 miles north of Guadalupe the train passes through a region wind-blown sand. On the left (west) as far as Bromela (bro-may'la) is a prominent ridge of sand dunes advancing upon rich farms. Farther north, between Bromela and Callender, the dunes have advanced far inland across the railroad, and the company has an expensive task in maintaining the roadway open. Between Callender and Oceano (o-say'ah-no) the advance is less rapid and lagoons have formed behind the sand. Just beyond Oceano, at the mouth of Los Berros Creek (Spanish for water cresses), Pismo Creek barely breaks through the barrier beach it has followed for 2 miles from Pismo.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/614/sec3a.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007