|

Geological Survey Bulletin 614

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part D. The Shasta Route and Coast Line |

ITINERARY

|

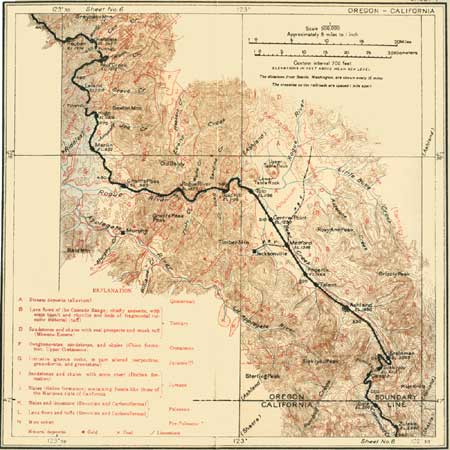

| SHEET No. 7 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Reuben. Elevation 1,376 feet. Seattle 445 miles. Glendale. Elevation 1,437 feet. Population 646. Seattle 449 miles. |

From Reuben spur (see sheet 7, p. 60) a wagon road leads to the Reuben Mountain mining district, which lies about 10 miles to the northwest. The prevailing rock of the region between Reuben and Glendale is greenstone.

Northwest of Glendale there are two prominent peaks of greenstone—Grayback, 4,033 feet above the sea, and Panther Butte, 3,517 feet. On leaving Glendale the train passes over a mass of siliceous reddish lava (rhyolite), and beyond this is the greenstone that forms the divide between Umpqua and Rogue rivers. The crest of the divide also forms the boundary between Douglas and Josephine counties. The dividing ridge is penetrated by a straight tunnel (No. 8), 2,828 feet in length and 420 feet below the summit. The basin of Rogue River is traversed by the railroad to the summit of the Siskiyou Mountains, a distance of 93 miles. Beyond the tunnel the railroad descends by a long sweeping curve into the Wolf Creek valley.

|

Wolf Creek. Elevation 1,319 feet. Population 232.* Seattle 455 miles. |

The station of Wolf Creek was formerly one of the hostelries on the old California-Oregon stage line. The small power house on the left (south) is the northernmost station on the power line from Gold Ray, 50 miles ahead on the edge of the Rogue River valley. Wolf Creek runs through a gold country, and in the early days many gold placers were worked in this vicinity.

Much of the primeval timber along Wolf Creek has been pine and oak, but madrona and other broad-leaved trees are now taking the place of the conifers. Buck brush (Ceanothus velutinus), with its broadly ovate or elliptical shiny leaves, and tree myrtle (Ceanothus sorediatus), with its small oblong ovate light-green leaves, are common in the thickets of chaparral in southern Oregon. Blue brush or California lilac (Ceanothus thyrsiflorus), with its tiny leaves and blue to white lilac-like flowers, which are good for cattle, soon appears in increasing numbers. By the roadside in June plants of the so-called Oregon grape or Mahonia (Berberis aquifolium), the State flower of Oregon, are full of bluish berries.

At milepost 497 the railroad crosses Grave Creek close to a placer mine, where water-supply pipes for hydraulicking and the gravel dumps left from former operations can be seen. Beyond Grave Creek is a broad belt of slates, probably for the most part Mesozoic. The name Grave Creek is suggestive of the old rough days of gulch mining, and the gravels along the creek did in fact yield considerable gold to the early placer miners. The metal in the placers is thought to have been derived by erosion from the Greenback lode, on the divide north of the creek. This lode was worked years ago, but the mine is now idle.

|

Leland. Elevation 1,218 feet. Population 239.* Seattle 463 miles. |

From Leland station there is a good view not only of the slates near by but also of the hilly country. Here the manzanita,1 which is abundant farther south, makes its first appearance. The railroad ascends Dog Creek to tunnel No. 9, which is at an elevation of 1,700 feet, is 2,205 feet long, and runs 300 feet below the summit. The tunnel is cut in black slates of Mesozoic age. On the right (west) as the train emerges is Tunnel Creek, down which it continues for about a mile and then, turning sharply to the left, enters an area of rock different from any yet seen along the route. Most people, including quarrymen, would call this rock granite, and such for all practical purposes it is. When fresh it has the characteristic gray speckled appearance of granite.2

1This shrub (Arctostaphylos patula), growing from 3 to 5 feet high in Oregon but much taller in parts of California, is sure to attract the attention of one who has never seen it before. It has a smooth bark of rich chocolate color, small pale-green roundish leaves, and berries that resemble diminutive apples. It is this resemblance that gives the shrub its common name, Spanish for little apple, by which it is everywhere known on the Pacific coast. Bears are very fond of these berries. The manzanita covers many hills in California with a stiff and almost impenetrable growth, as will be seen near Mount Shasta. Its wood is hard, and the blaze from an old gnarled root cheers many a western fireside.

2The geologist, who can with the microscope distinguish all the various minerals that compose rocks, has found that this rock is not strictly a granite but is intermediate in composition between true granite and a similar but darker rock containing less silica (quartz), known as diorite, so he would call it granodiorite. Like granite, granodiorite is an intrusive igneous rock. It was forced in molten condition, probably about the close of Jurassic time, into the slates and greenstones that now surround it, and then it slowly crystallized and solidified under a thick cover of rock that has since been worn away by erosion. Granodiorite is abundant in the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range.

|

Hugo. Elevation 1,316 feet. Seattle 469 miles. Merlin. Elevation 932 feet. Populatioa 787.* Seattle 474 miles. |

Hugo lies in the area of granodiorite, which is of irregular outline and extends southward for 15 miles, to the vicinity of Applegate River, beyond the town of Grants Pass. The rock at the surface is generally decomposed and crumbling, and is consequently more easily eroded than the harder slates and greenstones, and the country underlain by it is less rugged than that north of Hugo.

From Merlin a stage line runs to Rogue River, about 4 miles to the west, and down that stream to the Galice mining district. In the country beyond Merlin, on the left (northeast), an attempt is being made to establish orchards of apples, peaches, grapes, and other fruits without irrigation.

A low divide is crossed between Merlin and the town of Grants Pass, on Rogue River. Along the railroad may be seen cuts and quarries in the deeply disintegrated granodiorite, which is used by the railroad as a substitute for gravel about its stations.

|

Grants Pass. Elevation 963 feet. Population 3,897. Seattle 483 miles. |

Grants Pass, named after Gen. U. S. Grant, who as a captain quelled an Indian uprising on Rogue River in the early fifties, is the seat of Josephine County and the mining center of southwestern Oregon. From 1903 to 1912 the placer mines of this part of the State (Pl. XIV) produced $2,014,715 in gold, and the vein or lode mines $1,523,226. A stage line runs from Grants Pass through Kerby and Waldo to the coast at Crescent City, and a railroad to the same place is now under construction.

|

| PLATE XIV.—HYDRAULIC PLACER MINING IN GRANTS PASS REGION, OREG. |

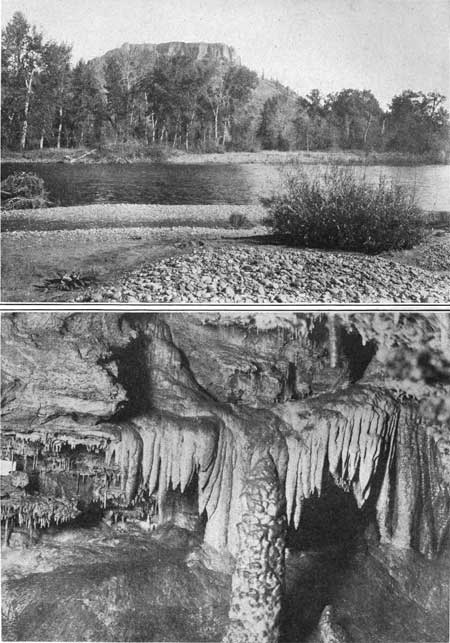

Grants Pass is the point of departure for a visit to the Oregon Caves, the largest caves known on the Pacific coast. The caves are about 25 miles nearly south of Grants Pass and may be reached by automobile and trail. They have been formed by the solution of limestone and are ornamented by a great variety of beautiful stalactites and stalagmites (Pl. XV, B) composed of carbonate of lime deposited by water. These caves have been set apart by the Federal Government for preservation as a national monument.

|

|

PLATE XV.—A. TABLE ROCK, AT ENTRANCE TO ROGUE RIVER VALLEY,

OREGON. A lava flow from the Cascade Range caps the softer beds and

protects them from erosion. B. OREGON CAVES, SOUTHWEST OF GRANS PASS, OREG. Stalactites, like icicles, hang from the roof of the cave; stalagmites point upward from the floor. When they meet they form a column. These forms are composed of carbonate of lime deposited from solution in water. Photograph copyrighted by Weister Co., Portland. |

Two miles beyond Grants Pass, at the eastern edge of the granodiorite area, is obtained the first near view of Rogue River, the largest stream of southwestern Oregon. Its water, derived in part from the snows about Crater Lake, is usually clear. The railroad for 20 miles upstream follows its valley, which is in places a canyon, but is generally wide enough to contain some tillable bottom land. The rocks through which this narrow valley has been cut are Paleozoic in age—much older than any rocks that have hitherto been seen along the route. They comprise slates, limestones, and greenstones and, like the Dothan and Galice formations, already noted, have been so folded and faulted that the Paleozoic rocks are thrust over upon the much younger Galice formation. These Paleozoic rocks resist erosion better than the granodiorite, and therefore the valley cut through them by Rogue River remains narrow.

At 3-1/2 miles east of Grants Pass, on the left (north), behind a little hill of granodiorite on Bloody Run Creek, is the Golden Drift placer mine, now idle. About 5 miles farther north is another small intrusive mass of granodiorite, about which are some small mines on gold-bearing quartz veins.

From milepost 469.4 up the river the Savage Rapids are in view. Old Baldy and Fielder Mountain, peaks of greenstone, stand out prominently on the left (north) from the point where the railroad crosses the line between Josephine and Jackson counties (milepost 469.1).

|

Rogue River. Elevation 1,025 feet. Seattle 492 miles. Gold Hill. Elevation 1,108 feet. Population 423. Seattle 499 miles. |

At Rogue River (formerly called Woodville) are fields of corn and wheat and young orchards. Nearly opposite milepost 462, on the right (south) side of the river, is the mouth of Foots Creek, whose gravels have for years been worked for gold.

At milepost 458, in the outskirts of Gold Hill, there are a limestone quarry and a cement plant. The limestone is a lenslike mass in a belt of slate more than a mile wide, which may be traced to the southwest for a long distance and contains numerous similar lenses of limestone. Fossils are rare in this limestone, but those found suggest Carboniferous age. Other limestone lenses, farther west in the area of Paleozoic rocks and not exposed on the railroad, contain fossils of Devonian age. Therefore the Paleozoic rocks of this region are in part Devonian and perhaps in part Carboniferous.

Rogue River is crossed just beyond Gold Hill, and the river bed affords a near view of some of the greenstone, which at this place is clearly made up of fragments of volcanic rock. The greenstones associated with the slates and limestones are in fact old lavas, partly poured out molten and partly blown out in fragments from volcanoes that were active in Paleozoic time. These lavas, originally black or gray, have become greenish through the slow changes of age. As will be seen later, these Paleozoic slates, limestones, and greenstones make up much of the Klamath Mountains.

After crossing the river the railroad turns northward opposite the hill from which the town of Gold Hill was named. This hill, which is 2,640 feet above sea level, consists of greenstone and serpentine, into which has been intruded some granodiorite that now forms the hilltop. Small "pockets" of rich gold ore were found here in early days.

Between mileposts 454 and 453 there is much of a coarse-grained dark rock composed chiefly of the mineral pyroxene (an iron-magnesium silicate) and called pyroxenite. This is an igneous intrusive rock and was probably very closely related to the rock that in the course of time changed into the serpentine of Gold Hill.

Northeast of Gold Hill, just across the river from the railroad, is Table Rock (Pl. XV, A), named from the flat black capping of basalt, which is part of a flow of lava that long before historic times spread over this region from some volcano in the Cascade Range. The lava flowed over comparatively soft beds of shale, sandstone, and conglomerate of Cretaceous and Tertiary age. Afterward erosion cut through the lava in places and attacked the softer rocks underneath, but Table Rock, with its protective capping, remains and shows how much has been washed away around it.

|

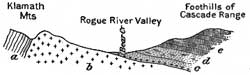

| FIGURE 9.—Section of Rogue River valley near Phoenix, Oreg. a, Slates, limestones, and lavas of Paleozoic (carboniferous?) age; b, granodiorite; c, cretaceous conglomerate, sandstone, and shale (Chico formation); d, sandstones and shales containing Eocene leaves; e, lava of Cascade Range. |

Beyond Table Rock the country opens out into that part of the valley to which the name Rogue River valley is especially applied. The valley lies between the Klamath Mountains on the west and the Cascade Range on the east. The highest point in view in the Cascade Range is Mount McLoughlin (9,760 feet), named after Dr. John McLoughlin, of the Hudson's Bay Co. The mountains are composed of relatively hard rocks, but the granodiorite and the Cretaceous and Tertiary sedimentary rocks that underlie the fertile fields of the valley are comparatively soft. This difference in hardness has enabled the river and its tributaries to carve out a wide, flat-bottomed valley. The sedimentary rocks of the valley lie in beds sloping eastward under the lavas of the Cascade Range, but they overlie the older rocks of the Klamath Mountains, including the granodiorite, and once extended much farther west. It will be noticed from the cross section (fig. 9) that the Cretaceous beds dip at a different angle from the slates of the Klamath Mountains and that, if they were restored to the west, they would lie across the upturned edges of the slates. This relation is known to geologists as an unconformity.

The train turns up the south east arm of the valley, drained by Bear Creek, which joins Rogue River near Table Rock, and passes through Tolo (elevation 1,196 feet, 452 miles from San Francisco) and Central Point (elevation 1,290 feet, 446.7 miles from San Francisco), where the traveler may see fine fruit orchards (Pl. XVI) and grain fields, before arriving at Medford.

|

| PLATE XVI.—PEAR AND APPLE ORCHARDS IN ROGUE RIVER VALLEY, OREG. |

|

Medford. Elevation 1,398 feet. Population 8,840. Seattle 514 miles. |

Medford, the chief town of the Rogue River valley, is rapidly growing in consequence of its relation to the fruit industry of the valley, the mining region of the Klamath Mountains on the west, and the forests and resorts of the Cascade Range on the east. From Medford the traveler may continue on the main line or make a detour, partly by automobile stage, through Crater Lake National Park, returning to the main line at Weed, Cal. The beautiful scenery of this side trip will amply repay anyone for the additional time it requires. To those interested in geology or in the ways by which mountains and valleys have come to their present forms the Crater Lake route will prove exceptionally interesting.

From Medford a short branch line (the Rogue River Valley Railroad) runs west to Jacksonville, and from Crater Lake Junction, a mile north of Medford, the Pacific & Eastern Railroad extends for 33 miles toward Crater Lake.

[The itinerary southward from Medford is continued on p. 56.]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/614/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007