|

Geological Survey Bulletin 707

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part E. The Denver & Rio Grande Western Route |

ONE-DAY TRIPS FROM DENVER.

(continued)

SOUTH PLATTE CANYON.

The canyon of South Platte River southwest of Denver offers many attractions to visitors from other parts of the world. There are no regular one-day excursions to this part of the mountains, but the train service on the narrow-gage Colorado & Southern Railway is so arranged that the traveler may easily visit such parts of the canyon as he deems most interesting and return to Denver the same day. If he is content with seeing the lower part of the canyon only he should go to the village of South Platte, 29 miles from Denver, but should he wish to see all its more rugged parts he should go as far as Estabrook, 52 miles distant. Many persons go to resorts farther up the canyon, even as far as Grant (66 miles), but this upper part of the canyon is not so rugged—it lacks the features that give to the lower part its peculiar charm. Those who go to the upper part do so on account of the fishing, which is reported to be unusually good.

On leaving the Union Station in Denver, the railway crosses South Platte River and runs up on the west side of the stream to the mountain front. At Sheridan Junction a branch line turns to the west (right) to Morrison, which is in the same valley as that in which Golden is situated. A mile up this line and on the main terrace that borders the river valley is Fort Logan, the largest military post in Colorado. The train passes some fine country places and goes through large areas of irrigated lands in a high state of cultivation.

At a siding called Willard, 17 miles from Denver, the traveler may see on his right a sharp-crested ridge, which is formed by the upturned edge of the Dakota sandstone, the same rock that forms the sharp hogback at Plainview, on the "Moffat road." At first this ridge seems to stretch along the entire-mountain front, and from the river bottom it appears almost as large as the mountains themselves, but on nearer approach it dwindles into comparative insignificance. The railway runs nearly parallel with this ridge for some distance, and then in following the river valley it turns more toward the west and cuts through it directly toward the mountains. The Dakota hogback on the south side of the river, as well as the outcrop of lower red sandstones, is shown in figure 5.

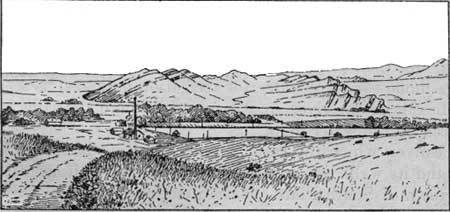

|

| FIGURE 5.—Dakota hogback south of south Platte River, looking south. Note the eastward dip of the sandstone forming the hogback and also that of the red sandstone nearer the mountains. Settling reservoir of Denver waterworks in the middle distance. |

The reservoirs of the Denver waterworks, in which all sediment is allowed to settle before the water is turned into the city mains, are at Willard. The reservoirs are tastefully arranged and beautified with flowers, so that they make a very pleasing appearance. After passing the settling reservoirs beds of red sandstone similar to those which make so striking an appearance in the Garden of the Gods, near Manitou, may be seen across the river, dipping away from the mountains at an angle of about 70°. Most of the beds of rock on the mountain front have similar dips, showing that at the time the mountains were uplifted the beds of sedimentary rock were bent up in a great fold, the upper part of which has been worn away, leaving only the suggestion of the upfold in the steeply inclined beds. Before the train reaches the mountains the great steel pipe that carries the Denver city water may be seen at several places on the right, where it spans the ravines on steel bridges.

Just above Waterton the train enters the mountains by a canyon cut in the hard granite. Here the city water main passes over the railway and then plunges into a tunnel through a projecting spur. A large flume carrying water for irrigation may also be seen on the opposite side of the river, and it passes through the same spur that is pierced by the water main.

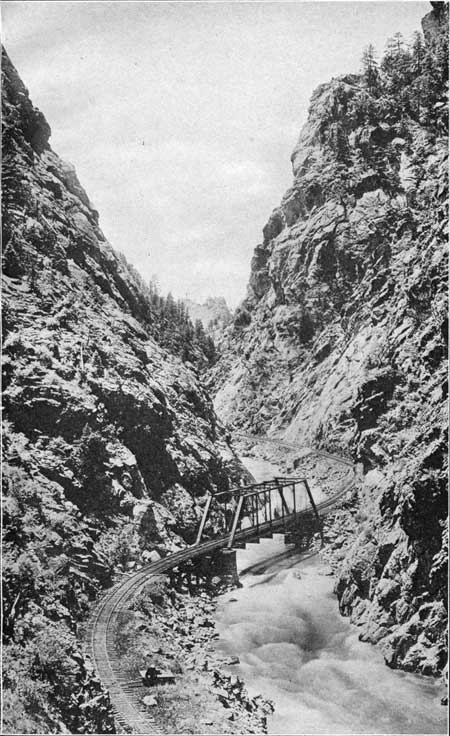

The canyon which the train is now following is narrow and tortuous, and its walls are generally rough and precipitous. It extends to the town of South Platte, at the junction of the two forks of the river. The course of the city water main on the opposite side of the stream may be followed by the white telephone poles up to the head gate. The canyon above this place differs in width in different localities. In some places it has a flood plain, but in others (as shown in Pl. X) it is so narrow that there is room only for the narrow-gage (3-foot) railroad beside the river, and this road has to curve as sharply as the stream.

|

| PLATE X. PLATTE CANYON. Narrow part of Platte Canyon, where even a narrow-gage railroad can hardly find a foothold. Photograph by L. C. McClure, Denver; furnished by the Colorado & Southern Railway. |

The one feature that differentiates this canyon from others in the mountain region is the great number of trees that dot the rocky slopes on both its sides, but more particularly on the southern. The soft verdure of the evergreen trees relieves the ruggedness and the barrenness of the rocky walls, giving the canyon a picturesqueness seldom seen in other canyons of this region. Pine and spruce are the most common trees, but here and there stand groups of aspen, with their ever-moving leaves, which in summer give a softness to the slopes and in autumn add a blaze of glory to the somber canyon walls.

South Platte is at the junction of the South and North forks of the river. South Fork, which is much the larger stream, drains nearly all of South Park and furnishes most of the water for the city's use. In the early autumn, when the snow has disappeared from the mountain tops, these streams are scarcely able to supply the city's needs. To remedy this deficiency a dam has been built some distance up South Fork valley to impound the water and hold it until needed. This dam has produced a fine body of water known as Cheesman Lake.

From South Platte the traveler may easily return to Denver, or if he chooses to go farther he can continue his journey up the canyon, which in some places takes on the aspect of a common mountain valley and in others is bounded by rocky walls several hundred feet high and so steep that they appear to be vertical. The massive granite, on weathering, tends to peel off like the layers of an onion, leaving a curved surface, in places like that of a great dome. (See Pl. XI, B.) Such a feature is well shown on a large scale at the station of Dome Rock. Where the granite is traversed by many fissures or joints it is so easily broken down that few ledges can be seen, and the surface is covered with a mantle of finely broken rock.

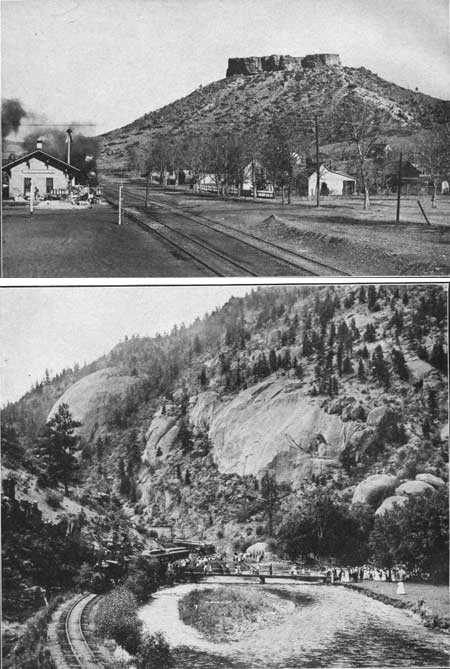

|

|

PLATE XI A (top). CASTLE ROCK. A well-known landmark about 300

feet high, 33 miles south of Denver. It was first noted and named by the

Long expedition in 1820. The cap rock, 60 or 70 feet thick, is made up

of boulders of various sizes cemented together (conglomerate) and stands

out prominently because it is harder than the underlying rock.

Photograph by L. C. McClure, Denver. B (bottom). DOME ROCK, PLATTE CANYON. This picture illustrates the manner in which even the most massive granite may yield to the action of the weather. It peels off in successive curved layers much like the layers of an onion, leaving round or dome-shaped masses of rock which stand out in striking contrast to the towers and pinnacles that generally occur on the walls of the canyon. Photograph by L. C. McClure, Denver; furnished by the Colorado & Southern Railway. |

The roughest part of the canyon above South Platte lies between Cliff and Estabrook, where the gneiss is again exposed and makes a narrow, rugged defile. This canyon, like the one below it, has several aspects, which depend upon the character of the rock and upon the position of the joints.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/707/trip1b.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2007