|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

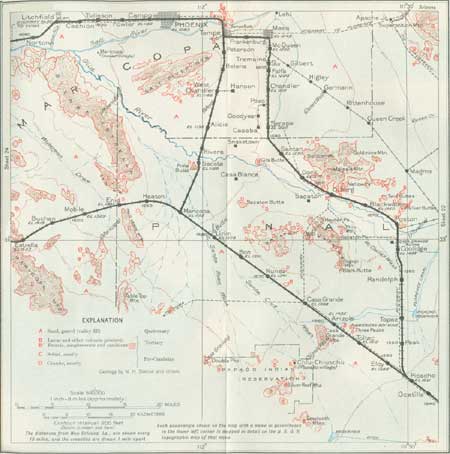

SHEET No. 23 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

OLD MAIN LINE, PICACHO TO WELLTON, ARIZ.

Until 1928 the trains of the Southern Pacific lines continued northwestward from Picacho to Wellton via Maricopa, where there is a branch to Phoenix. Now most passenger trains pass over a new line northward from Picacho to Phoenix and thence down the north side of the Gila Valley to join the old line at Wellton, as just described. The old line from Picacho to Wellton is described below.

|

Eloy. Elevation 1,566 feet. Population 13. New Orleans 1,549 miles. |

Near Eloy siding (see sheet 23, p. 206) an irrigation district which extends to Casa Grande is entered. Cotton and alfalfa are the principal crops, together with melons, figs, and a fine variety of head lettuce for which the soil and climate seem particularly suitable. The lettuce is ready for shipment in November, before it is available from competing districts. The water is brought by ditches from the Gila River near Florence, and considerable water is also pumped from wells in the valley fill using electricity as an economical source of power.

|

Arizola. Elevation 1,435 feet. Population 30.* New Orleans 1,559 miles. Casa Grande. Elevation 1,398 feet Population 1,351. New Orleans 1,564 miles. |

About midway between Toltec siding and Casa Grande the railroad passes north of the Casa Grande Mountains, a group of rugged peaks of pre-Cambrian schist, Three miles to the northeast are the Three Peaks, which consist of granite. About 15 miles southwest of Toltec are the conspicuous Sawtooth Mountains, which consist of lavas of Tertiary age.

Casa Grande is on a broad, smooth plain of sand and loam (valley fill), in which the slope of the land is scarcely perceptible. The mean annual rainfall is about 6-1/2 inches. About 18 miles northeast of Casa Grande station are the ruins of the prehistoric houses of Casa Grande, which are near the railroad on the main line from Picacho to Phoenix. (See p. 197.) Nine miles south of Casa Grande is the Papago Indian village of Chiu-Chiuschu (population 349), where there is a school and a pumping plant to obtain water for irrigation. Many detached mountains and rocky buttes are visible in all directions from Casa Grande and vicinity.58

58About 15 miles to the south are the Slate Mountains, which consist largely schist overlain to the west by an interesting succession of Paleozoic rocks comprising Bolsa quartzite and Abrigo limestone (Cambrian) and Martin (Devonian) and Carboniferous limestones. The Abrigo beds at this place consist of slabby brown sandstones, in part glauconitic (greensand), with brown and gray shales. They contain worm markings and lingulas of Cambrian age. The overlying limestones (Martin) carry abundant Upper Devonian fossils that indicate an extension of the sea waters of Paleozoic time over much of western Arizona.

The low range of buttes rising abruptly from the plain a few miles north of Casa Grande and extending thence westward are the Sacaton Mountains, which consist of massive light-colored granite (mica diorite). There is a small knob of this material 3 miles northeast of Nuñez siding, and it appears in many of the ranges to the north and west. It is an intrusive rock which has been forced up in molten condition through the old schist in pre-Cambrian time.

|

Picacho. Elevation 1,175 feet. Population 30.* New Orleans 1,585 miles. |

At the small station of Maricopa is the branch line to which formerly passengers for Phoenix were transferred. Now, however, as explained on page 224, most of the trains go directly to Phoenix from Picacho. Maricopa is situated on a broad desert plain not far from the Santa Rosa Wash and the Santa Cruz River, both of which are generally dry. In this vicinity there is a small amount of irrigation by water pumped from wells. Many mountains rise abruptly from this plain, the Sierra Estrella to the north and the Palo Verde Mountains to the west, which are continued southward by various ridges of schist and granite to the high Table Top Mountains, 25 miles south of Maricopa. This range, which does not appear distant, culminates in a flat-topped peak that has an elevation of nearly 4,000 feet and consists of a cap of basalt presenting steep cliffs on all sides. Some distance northwest is the steep conical summit known as Antelope Peak, composed of a sheet of lava dipping at a steep angle. Below these lavas are granites and schists rising to an irregular plane which in Tertiary time was a general surface on which the lavas were poured out. Subsequent uplift, tilting, and erosion have left the remnants of the lava flows perched high above desert level, a feature which is general in a large part of southwestern Arizona.

West of Maricopa the railroad ascends slightly to reach at Enid siding the wide pass between the Sierra Estrella on the north and the Verde Mountains on the south, The Sierra Estrella is a very prominent range which extends 25 miles north to the mouth of the Salt River, with an average width of 3 miles and a maximum height about 3,000 feet above the plain. Montezumas Head, at the south end, has an elevation of 2,406 feet. The northeastern front of the range is very steep and rugged up to about 2,000 feet, where some of the canyons open into valleys. The range consists mainly of schist, but this rock is invaded by large intrusive masses of granite, one of which at the south end extends nearly to the railroad. A granite aplite intrusion occupies an area of 5 or 6 square miles between North Peak and the Webb mine. Dikes of coarse granite and diabase also occur.

The Palo Verde Mountains, south of the gap at Enid, consist of schist and are part of a line of ranges extending south through the Vekol59 and Cimarron Mountains. They are about 800 feet high, deeply canyoned, and possibly bounded by a fault at their steep northeast end. In the pass between the Palo Verde and Table Top Mountains, the range next south, there are ledges of Tertiary arkosic conglomerate interbedded with basalt flows, the lowest of which rests on granite. The beds dip 14° SW. Some of the boulders, which are granite, are 6 to 8 feet in diameter.

59South of the Table Top Mountains, about 45 miles south of Maricopa, are the Vekol Mountains, which are of great geologic interest, for they contain not only a succession of Paleozoic limestones including some strata of Permian age but an outlying mass of formations of the Apache group (Algonkian) lying on pre-Cambrian schist and closely resembling the succession in central Arizona. Some hard red shale at this place resembles the Pioneer shale, and it is capped by a conglomerate like the Barnes. An overlying quartzite like the Dripping Spring quartzite is penetrated by thick sills of dark-green diabase. Next above are rusty sandy shales grading up into thin-bedded limestone containing Upper Cambrian fossils, undoubtedly the Abrigo limestone. The higher limestone in an adjoining ridge carries a remarkable fauna of minute fossils, pelecypods, scaphopods, and gastropods, of about 25 species of late Carboniferous age.

The wide plain of the Estrella Desert is crossed west of Enid to reach a low pass through the northern part of the Maricopa Mountains. This pass is drained by Waterman Draw, and wells in the valley fill near this draw have obtained sufficient water for cattle, which find sparse pasturage in the valley and adjacent slopes. The divide is just east of Estrella siding (elevation 1,523 feet), where there is a wide gap floored with gravel and sand between high granite ridges. Wells drilled in the valley fill at Mobile siding (452 feet deep), at Ocapos siding (541 feet deep), and at Estrella found water which rose high in the borings but was insufficient in quantity for locomotive use. It was through this pass that Padre Garcés traveled in 1775 on the way to Yuma, and he called it Puerto de los Cocomaricopas. (See p. 194.)

|

|

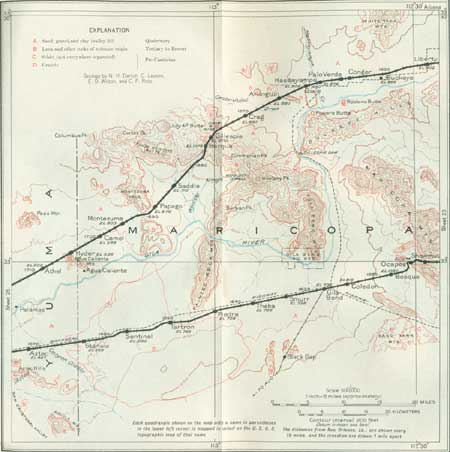

SHEET No. 24 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Beyond the Estrella divide (see sheet 24) the railroad descends to Ocapos siding in a wide valley with walls of granite. The Maricopa Mountains consist mostly of this rock, with a minor amount of schist. The east slope of this range north of Estrella has at its foot a moderately wide pediment or slope of nearly bare rock, trenched but slightly by streams. At one place this pediment is surmounted by a hill of gravel capped by a remnant of a basalt sheet tilted to the east, which indicates uplift since the extrusion of the lava. On the west side of the mountains and in the pass there is a thick mantle of valley fill.

South of Bosque siding are the Sand Tank Mountains,60 which consist of a long, high ridge of schist and granite and a high, wide tabular mesa of volcanic rocks in a succession nearly 2,000 feet thick. This region was a center of great volcanic activity in Tertiary time, when widespread sheets of lava were poured out over the land. These have since been uplifted, tilted, faulted, and greatly eroded.

60At the Sand Tanks, a watering place in these mountains 23 miles southeast of Gila Bend, the water is found in holes eroded in a conglomerate of Tertiary age which dips 20°; N. This rock lies on granite gneiss and consists mostly of tuffs and sandy tuffs containing pebbles of granite, schist, and volcanic rocks of various kinds. The schists in the central ridge are mostly chloritic, and there are many transitions from schist to gneiss. Fine-grained biotite granite and phyllite also occur.

|

Gila Bend. Elevation 738. Population 800.* New Orleans 1,627 miles. |

Gila Bend is a town sustained by cattle, irrigation, and mining interests and is the headquarters for the Gila Bend Indian Reservation, near by, where there is a colony of about 224 Papago Indians. The climate is very dry, with a mean annual precipitation of only 6 inches. A branch railroad connects Gila Bend with Ajo (ah'ho, Spanish for garlic), 30 miles to the southwest, a copper-mining town which has a population of 3,003. Copper has been mined at Ajo since 1855, mainly from the Cornelia mine. Most of the ore carries less than 1-1/2 per cent of copper, but it is easily worked and occurs in large amount. The ores are mainly disseminated in monzonite porphyry and a small amount is disseminated in veins in rhyolite and tuff, into which the porphyry is intruded. It is estimated that 40,000,000 tons of ore is available. There are also dikes of diorite and later porphyry, all presumably of Tertiary age. In 1929 a total of 3,582,000 tons of ore containing from 1 to 1-1/4 per cent of copper was treated.

South of Gila Bend are the Sauceda Mountains, a high range consisting mainly of a thick succession of Tertiary volcanic rocks of which the latest member is basalt. Hat Mountain, a prominent landmark 25 miles south of Gila Bend, has a cap of this basalt, a remnant of a lava flow of Tertiary time.

Gila Bend is in the broad valley of the Gila River, which in making its huge bend southward around the Gila Bend Mountains approaches within 4 miles of the town. In this region the river is a wide water course which ordinarily carries only a small flow. It was in this vicinity that Padre Kino found a prosperous Opa (Maricopa) Indian ranchería in 1699, and it was visited in 1774 by Anza and Garcés, who called it the Pueblo de los Santos Apóstoles San Simón y Judas. There were other rancherías along the river at which the Indians were raising two crops of grain a year by irrigation with river water. This was the farthest east that the Maricopa Indians had advanced up the river, but they have since moved to the region southeast of Phoenix.

The valley fill here is thick, for borings 1,530 to 1,780 feet deep, for water, appear not to have reached bedrock, unless "hard beds" in the lower 550 feet are Tertiary or Cretaceous. In the surrounding region there is a succession of older beds of gravel and sand61 which are mostly tilted and in places faulted. They are overlapped unconformably by the later sand and gravel that floor the valley. There are excellent exposures of these relations on the slopes of the Gila Bend Mountains near Woolsey Well, 15 miles northwest of Gila Bend, and farther west at the north end of the Gila Bend Mountains west of Dome.

61These older beds are in general correlated with the Temple Bar conglomerate of Lee and the Gila conglomerate of Gilbert. In places they include lava flows (basalt) which are tilted and faulted.

As the Gila Valley below Mesa is filled with a thick mass of alluvium underlain in part by sandstone of Tertiary age, it is evident that the region was 1,000 feet or more higher when the valley was being excavated than it is now, and it has sunk to its present level as the younger formations were deposited. Possibly this loading was the cause of the sinking, but more likely it was due to some widespread crustal movement. A notable feature revealed by the logs of deep borings in the valley is a deposit of clay of wide extent, with a maximum thickness of 860 feet at Gila Bend. This clay must have been deposited in quiet waters, such as those of a lake or estuary that continued for a long period of time. The deposition of clay was followed by the accumulation of coarser material spread by streams, and since that time terraces higher than the present bottom lands have been developed. In places these later deposits were flooded by lavas, through which the present river trench has been excavated nearly 100 feet. From the historical record the Gila River channel has changed materially in a century or less. When it was originally discovered there was a well-defined channel with hard banks sustaining cottonwoods and other trees and plants. The current was swift and deep in places, so that the stream could be navigated by flat boats of moderate size, and it contained sufficient fish to be relied upon as food for many Indians. It was reported also that the water was clear and sea-green, very different from the present muddy stream. Now the Gila River is depositing sediment in its lower part, and its braided course follows many narrow sand-clogged channels. Possibly these changes may be due partly to diverting and damming the water and to an increase of silt caused by the removal of forest and increased grazing in the higher region.

Irrigation has been practiced in this region for a very long time, for old Indian ditches are found near the Painted Rock Mountains below Gila Bend and at other places along the river flats. Irrigation was again started in a small way by settlers who came soon after the bimonthly stage line between San Antonio and San Diego was established in 1857. The area under cultivation was small, but it was increased somewhat in the early seventies, and continued intermittently until 1905, when a heavy flood destroyed most of the canals. Some of these canals have since been restored and new ones developed, but the principal enterprise now in operation is the utilization of water held by the Gillespie Dam, 20 miles north of Gila Bend. (See p. 219.)

The lower Gila River Valley figures prominently in the chronicles of many of the early explorers of Pimería Alta. When Kino explored this valley in 1699 and 1700 and Garcés in 1771 and later, they found many Indian rancherías and some irrigation, but the adjoining region was so inhospitable that it supported only a meager population. The Pimas and some Papagos dwelt on the banks of the Gila near the mouth of the Salt River, and these streams furnished water for considerable irrigation. The Maricopas, who were of Yuman stock, moved gradually up the Gila Valley, pausing at Gila Bend in Garcés' time and finally reaching the Phoenix region, where many now reside with the Pimas. The Yavapais or Apache-Mojaves lived in part in the region between the Colorado and Gila Rivers. In early days they were friendly to the whites, but after suffering various injustices they went on the warpath in 1868 and were troublesome for several years. Oatman Flat, on the Gila River a few miles northwest of Gila Bend, was the scene of an Apache attack in 1851; in which an emigrant named Oatman and his family were killed, except a young son who escaped and two daughters who were carried off. The girls were sold as slaves to some Mojave Indians, and one who survived was ransomed seven years later. This case attracted much attention and was the subject of a narrative62 that had a large circulation.

62Stratton, R. B., Captivity of the Oatman girls and an account of the massacre of the Oatman family in 1851, San Francisco, 1857; New York, 1858.

North and northwest of Gila Bend the Gila River resumes its westerly course. The steep Gila Bend Mountains, which are in sight from the railroad for many miles, consist largely of granite with a thick succession of Tertiary volcanic rocks overlapping it on the west. These younger rocks are thick in Woolsey Peak in the center of the range, which is made up of light-colored lavas and some fragmental volcanic rocks. On the western extension of the range these rocks are capped by a thick sheet of dark-colored basalt, constituting prominent mesas. One of the highest and most extensive of these mesas is called Yellow Medicine Butte. About 14 miles north of Piedra station a large basalt-covered cuesta extends with a long slope to the Gila River, which swings north in order to pass between it and the north end of the Painted Rock Mountains. The railroad, on the other hand, passes near the south end of these mountains, near Piedra and Tartron sidings. The Painted Rock Mountains consist of lavas of Tertiary age, capped in part by basalt, tilted, faulted, and considerably eroded. The name is derived from Indian pictographs on bluffs near the river.

|

Tartron. Elevation 729 feet. New Orleans 1,650 miles. Sentinel. Elevation 690 feet. New Orleans 1,656 miles. |

On approaching Tartron siding the railroad climbs a few feet to the nearly level surface of a broad sheet of lava of relatively recent age which extends about 17 miles, to a point beyond Stanwix siding. This flow, which is wide to the north and south, doubtless came from several vents. The remains of one crater, probably a source of a considerable part of the lava, is a knob of moderate height 1-1/2 miles northwest of Tartron siding. A long ridge southeast of Sentinel siding probably marks another outlet. The lava, which is thin near its edges, lies on gravel and sand and is of recent origin compared with the lavas constituting the summits of the high adjoining ridges that have been uplifted and in large part widely removed and cut back by erosion. This recent lava undoubtedly dammed the Gila River for a while, but the stream has since cut a trench about 100 feet deep across its northern portion. In places the younger lava abuts against slopes of the older volcanic rocks, and it occupies valleys developed since the older rocks were flexed and faulted, a condition indicating a long-time interval. Several wells at Sentinel siding pass through 60 to 100 feet of this lava and obtain a good water supply from the underlying sands, which were penetrated to a depth of 1,129 feet.

From the Sentinel Plain there are extensive vistas across the desert to the lofty Growler Mountains, far to the south; to the commanding and nearer Aguila Mountain (ah'ghee-la), to the southwest, culminating in a high northward-sloping plateau of lava; and to the Aztec Hills, to the west. Back to the southeast Hat Mountain (p. 227) is conspicuous. To the north are many ranges, mostly of volcanic rocks, which lie beyond the Gila Valley.

In this part of Arizona the railroad crosses wide desert plains, mostly covered by creosote bush (Covillea). Very little of this land can be reclaimed by irrigation, on account of the scanty water supply. The question of water is the most important consideration in these desert regions, not only for domestic use and for locomotives, but for the cattle industry, which can not exist without it. Tanks created by damming draws hold some of the rainfall, but the loss by evaporation is very great in this region, the depletion averaging more than 6 feet a year. The Gila River is the only stream that runs continuously, and the few springs that exist are widely scattered. A small amount of water is held in natural basins in the rocks, known locally as tinajas (tee-nah'has, Spanish for large earthen jars). Wells find water in the gravel and sand of the desert, in crevices in rocks of the mountains, and under some of the lava flows, but the amount is generally small. The scant rainfall wets the soil and in large part evaporates, but some of it passes underground into the coarser materials, which occur mostly along the sides of the valleys. The water is available in some places in the valleys, but ordinarily it is only sufficient for domestic use or for a few cattle. Along the river flats there is a ground-water plane sustained by the streams and extending laterally for some distance; this is the source of supply for many wells, some of which in the lower Gila Valley yield water for irrigation. In the lower part of the Salt River Valley also the underflow is extensive and in much of the area of ample volume.

The desert landscape has many peculiarities. At first sight its wide gray plains and bare mountain slopes seem forbidding and monotonous. However, they have a certain grandeur and present attractive variations in light and shade during different portions of the day and from day to day. Some of the sunsets are particularly beautiful. Under the direct rays of the midsummer sun the heat is intense, but ordinarily the low humidity keeps the skin comfortable, and there is much less suffering from the heat than in a moist region at much lower temperature. Mirage is frequent, especially the sort due to a film of vibrating hot air near the ground, which gives the illusion of distant lakes. In the higher mountains precipitation is greater than in the valleys, the temperatures are lower, and occasionally there is snow. Everywhere the rains are followed by rapid growth of many flowers. The desert region of the southwest corner of the United States is a part of the Sonoran Desert, which extends north from the State of Sonora in Mexico and is very much of a unit in climate, vegetation, and general aspect. Rainfall, which ranges from 3 to 6 inches a year in the region west of Phoenix, comes mostly in widely separated heavy downpours in narrow streaks, many of them "cloudbursts," which give rise to local sudden freshets of great volume. One of these in 1930 washed out a large part of Wellton. Some floods are not confined to a channel but extend widely over the valley floor.

Sand storms occur occasionally on the deserts of New Mexico, Arizona, and southern California, but most popular accounts of them are greatly exaggerated. The following description (by C. P. Ross) will give some idea of a typical sandstorm. It followed showers in the mountains and came from the southeast, where at frequent intervals before, during, and after the blow there were sharp claps of thunder. At first there came bodies of flying sand in long, thin pillars reaching far upward and resembling waterspouts in shape and appearance but moving with much greater speed. These were followed by billowing clouds of sand, which, however, did not transport much material, and then came the main blow in dense waves and carrying a large percentage of fine sand. Where these waves struck the mountains they were shattered, and the sand was whirled high on the foothills, much like waves of water driven by a hurricane. In 10 to 15 minutes from the coming of the first sand the storm diminished, especially as to the amount of sand. During the height of such a storm it is difficult to travel, mostly because the sand is blinding. It also penetrates the clothing and fills the hair and every wrinkle of the skin not well protected, so that it is somewhat uncomfortable, but there is almost no cutting of the skin. Sand storms as severe as this are rare.

|

Aztec. Elevation 497 feet. Population 40.* New Orleans 1,671 miles. |

A 710-foot well at Aztec yields an excellent water supply. Below 145 feet of sand it penetrated 455 feet of red clay, an extension of the thick bed penetrated by deep borings at Gila Bend. Three miles due south of Aztec and conspicuous from the railroad is a white quartz knob that is on a spur of the Aztec Hills, which consist mostly of schist and granite. At the west end of these hills, 4 miles west of Aztec and about a mile south of the railroad, there is a quarry in schistose granite, which is crushed for use on the roads. (See sheet 25.)

|

|

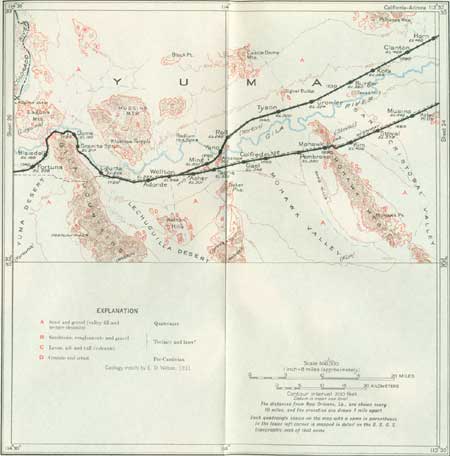

SHEET No. 25 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Stoval. Elevation 378 feet. Population 30.* New Orleans 1,682 miles. |

Texas Hill, 6 miles northwest of Stoval, is a small butte on the north bank of the Gila River consisting of basalt, probably part of a small flow. Near it Garcés camped in 1775 in company with Anza's expedition to California. The old settlement of San Cristóbal, of which the station name is an abbreviation was near this hill. Saints' names were sprinkled over the country by all the early explorers, and most of them do not indicate the presence of a mission. West from the Aztec Hills is a wide desert known as the San Cristobal Valley extending to the foot of the Mohawk Mountains. A well sunk 700 feet in the valley fill at a point about 4 miles south of Stoval found considerable water, which it was hoped could be used for irrigation. This valley, like many others that lead to the Gila River, is not trenched by its stream except where it approaches the river, north of the railroad, but its bottom is a broad adobe flat.

|

Mohawk. Elevation 545 feet. New Orleans 1,690 miles. |

The northern part of the Mohawk Mountains is crossed by the railroad in a moderately high, rocky gap at Mohawk. These mountains are very rugged and bare and consist largely of pre-Cambrian schist penetrated by granite. Contacts of these two rocks are visible near the railroad. At the north end of the mountains the schist is flanked by a thick succession of conglomerate, sandstone, and shale of probable Tertiary age, dipping steeply to the southwest. The granular schist a short distance northwest of Mohawk, which is quarried for road material, contains veins of barite that have been mined in small amount. Five miles south of the station, on the east side of the mountains, is the old Norton or Red Cross mine, which produced a small amount of rich silver ore many years ago. The rock pediment on the west foot of the mountains is heavily flanked by loose sand, which has been blown by the wind and accumulated at the foot of the slope. Farther north, near the railroad, this pediment is deeply trenched by small arroyos. At the north end of the Mohawk Mountains is the Gila River; at this place Garcés in 1775 crossed to the south side of the river. The Mohawk Mountains were named Cerro de San Pascual by Anza on his expedition of 1774; he camped at their north end the following year.

West of the Mohawk Mountains is the wide desert plain of Mohawk Valley, which extends west for about 15 miles to a line of ridges consisting of the lava-capped Cabeza Prieta Mountains (cah-bay'sa pre-ay'ta, Spanish for black head), to the south; the Copper Mountains, a conspicuous rugged range of granite southwest of Colfred siding; and the Baker Peaks, a short distance south of Tacna siding. The prominent Baker Peaks, named for Charles Baker, who in early days ran a ferry across the Colorado River at Yuma, consist of tilted sandstones presumably of Tertiary age.63 South of the Baker Peaks are ridges of conglomerate, also of Tertiary age, extending to the flank of the Copper Mountains. Far to the north are the fantastic summits of the Castle Dome Mountains. Closer at hand to the northeast from Colfred siding is Signal Butte, rising prominently above the desert plain a scant 5 miles beyond the Gila River. It is a small mass of basalt probably marking the center or outlet of a minor lava extrusion.

63These rocks are well exposed at Baker Tanks, 5 miles south of Tacna, where the conglomerate dips 65° SW. The beds are mostly an aggregate of quartz and feldspar grains, but some beds are a coarse conglomerate with many pebbles and boulders from 3 inches to 3 feet in diameter. The material is so similar to gravel deposited by present streams on the slope of Baker Peaks as to indicate that it was derived from the same rocks under conditions similar to those which now exist.

A mile north of Tacna siding and extending for a mile to the bank of the Gila River is Antelope Hill, about 600 feet high. It consists of grayish arkose composed largely of granite debris and probably of Tertiary age. The dip is to the south at a low angle, and about 500 feet of beds are exposed. There are also small exposures of this rock in smaller buttes just north of the railroad 2 miles farther west, in which the dip is 15° SW., and another small exposure northeast of Antelope Hill. The material has been quarried extensively, mainly for road metal.

At Wellton the old main line of the railroad is joined by the new line from Picacho by way of Phoenix. (See p. 223.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec24a.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007