|

Geological Survey

John Wesley Powell's Exploration of the Colorado River |

|

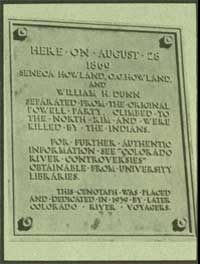

| Plaque on the eastern side of Separation Canyon, marking the place where the Howland brothers and William H. Dunn left the 1869 Powell expedition. |

On August 16, they camped, remaining for a few days on a sandy beach above the mouth of a clear, glistening creek that Powell later called "Bright Angel." Here they whittled new oars from driftwood, recalked the boats, and dried out their rations once again. The bacon was badly spoiled and had to be thrown away. Their store of baking soda had been lost over board, so they could have only unleavened bread to eat.

Ten days later, while still in the canyon, they came again to the dreaded granite. At noon on August 27, they approached a place in the river that seemed to be particularly threatening. Boulders that had been washed into the river formed a dam over which the water fell 18-20 feet. Below the boulder dam was a 300-foot-long rock-filled rapids. On the side of the gorge, rock points projected from the wall almost halfway across the river. They tried in vain to find a way around it but finally concluded that they had to run it. There were provisions for only 5 days more.

Some of the men thought they should abandon the river. Captain Howland, his brother Seneca, and William Dunn decided to leave the party and go overland to the Mormon settlements about 75 miles to the north.

|

| Climbing the Grand Canyon wall. |

For the last 2 days the course had not been plotted, and Powell now used dead reckoning to determine their way. He found that they were only about 45 miles from the mouth of the Virgin River in a direct line, but probably 80-90 miles from it by the meandering line of the river. If they could navigate the remaining stretch of unknown water to that point, he reasoned, the journey up the Virgin River to Mormon settlements would be a relatively easy one.

Powell spent the night pacing up and down on the few yards of a sandy beach along the river. Was it wise to go on? While he felt that they could get over the immediate danger, he could not foresee what might be below. He almost decided to leave the river, but wrote, however:

For years I have been contemplating this trip. To leave the exploration unfinished, to say that there is a part of the canyon which I cannot explore, having already nearly accomplished it, is more than I am willing to acknowledge and I determine to go on.

August 28—At last daylight comes, we have breakfast, without a word being said about the future. The meal is as solemn as a funeral. After breakfast I ask the three men if they still think it best to leave us. The elder Howland thinks it is, and Dunn agrees with him. The younger Howland tries to persuade them to go with the party, failing in which, he decides to go on with his brother.

Before they parted, Powell wrote a letter to his wife and gave it to Howland together with one copy of the records of the trip. Sumner gave Howland his watch asking him to send it to his sister should he not be heard from again. It was a solemn parting; each thought the other was taking the more dangerous course.

They divided the scanty rations and the guns and ammunition. The small boat was abandoned. First three men in one boat ran the rapids, then three in the other.

We are scarcely a minute in running it, and find that, although it looked bad from above, we have passed many places that were worse . . . We land at the first practicable point below and fire our guns, as a signal to the men above that we have come over in safety. Here we remain a couple of hours, hoping that they will take the smaller boat and follow us. We are behind a curve in the canyon, and cannot see up to where we left them, and so we wait until their coming seems hopeless, and push on.

Later Powell learned that the three men had been killed by Shivwits tribesmen who, not believing the story of their coming down the canyon by way of the river, mistook them for miners who had molested a squaw.

Early on the morning of the 29th, the expedition again started downriver. At about 10 o'clock the country began to open up. On the 30th, they came, somewhat unexpectedly, to the mouth of the Virgin River. On September 1, Sumner, Bradley, Hawkins, and Hall took a small supply of rations and continued downstream. Their intention was to go on to Fort Mojave and then overland to Los Angeles. Major Powell and his brother left for Salt Lake City and then home.

|

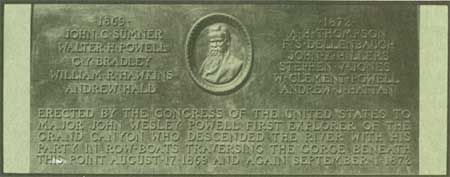

| Plaque on the monument erected by Congress to commemorate the Powell expedition. |

Although Powell returned a national hero, he was not satisfied with the results of his exploration. Notes had been lost; the few specimens collected had been cached. The scientific instruments had been badly damaged and the information obtained was not as complete or reliable as Powell wished.

Consequently, he planned an other expedition to supplement the work of the first. By spring 1871, everything was ready for Powell's second exploration of the Colorado River, its tributaries, and its canyons. Congress had appropriated funds, the members of the party had been selected, and three boats of improved design were waiting at Green River Station, Wyoming Territory.

On May 22, 1871, the party pushed their boats out into the stream—.

| <<< Previous | <<< Cover >>> | Next >>> |

inf/powell/sec9.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006