|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 3

The Geology and Petrography of Crater Lake National Park |

THE GEOLOGY OF CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK

By JOSEPH SILAS DILLER.

MOUNT MAZAMA.

(continued)

LAVAS OF MOUNT MAZAMA.

(continued)

DACITES.

Dacites are much less abundant than andesites in the rim of Crater Lake, but unlike the basalts, they come from the same general vent. They are very unequally distributed. One flow is on the southern slope some distance from the summit; the others are along the northern crest of the rim and are later than the andesites, excepting only the andesite of Wizard Island. The separate flows to be considered are those of Sun Creek, Cloud Cap, Grouse Hill, Llao Rock, Wineglass, and Cleetwood Cove. Among them there is wide variation, from obsidian through spherulitic to well-banded and largely crystalline material, while some are mud flows streaked with black glass.

SUN CREEK DACITE FLOW.

The canyon of Sun Creek below the falls has upon the west a number of cliffs and terraces, due to successive flows of dacite, exposing a total thickness of about 600 feet. At 6,300 feet east of Crater Peak the cliffs begin. The first is 200 feet, made by a solid flow of dacite with conspicuous structural features. The next terrace, at 5,900 feet, exposes a decidedly perlitic and spherulitic rhyolite banded with small lithophysae, and forms a bluff 75 feet in height. There are bands of perlitic and spherulitic grains alternating with others which show neither structure. At 5,700 feet is a plain of fine material, filling the valley to a width of three-fourths of a mile. In the soft material Sun Creek has cut a canyon 200 feet deep. Upon the eastern side in the canyon wall dacitic rocks (123, 124) appear, containing cavities lined with minute crystals of tridymite. The layer of pumice covers nearly everything beyond the canyon, so that the nature of the underlying rock is to a considerable extent a matter of doubt. On the West Fork of Sun Creek, just above where it begins to cut a canyon in the material filling the valley, masses of dacite (125, 126) appear, and if not in place have not been moved far, for the rocks immediately to the north are andesite. On the spur between the West Fork and the main stream of Sand Creek a well-marked dacite (127) occurs, with conspicuous fluidal banding and aligned cavities sparkling with tridymite; it appears to form the whole ridge excepting the small capping of andesite. A short distance farther north a strong spring issues from the contact between the dacite and the overlying andesite.

The Sun Creek dacite is the oldest about Crater Lake. It is evidently older than the andesite which lies upon it at an altitude of 6,600 feet. This is considerably above the level of the lake, and if the rhyolite came from Mount Mazama it should appear on the inner slope of the rim under Dutton Cliff. From a boat by the shore the cliff was examined to see if the dacite flow could be recognized, but it was not found.

CLOUD CAP DACITE FLOW.

Cloud Cap is on the eastern crest of the rim and marks the point of departure of a stream of dacite which spreads to the northeast. It forms a large part of Redcloud Cliff, which takes its name from the reddish-yellow tuff or tuffaceous dacite that underlies the principal flow. This flow, or, rather, group of flows—for it appears to be made up of at least three streams—forms a prominent cliff for over half a mile along the rim and has a thickness of over 300 feet. It appears to form one-third of the inner slope of the crest. This flow presents a series of great cliffs about its borders, especially on the northwest. The finest is upon the west side nearly half a mile from the lake. It is 250 feet high and of great length, smooth and polished as if by glaciers, but distinct striae could not be found. The rock (118) is especially glassy, often banded with brown, and may be finely spherulitic or lithophysal. The canyon heading between Cloud Cap and Scott Peak presents cliffs which are less imposing. Upon the east side of this canyon at the northern end of the flow the rock, although dacite, is more massive and lacks the vitreous features of the main body of the flow near its source. To the west this series of dacite flows, along the southern arm of Grotto Cove, may be seen to overlie the adjacent streams of andesite. The base of the dacite flow near the contact is glassy, with numerous spherulites and lithophysae.

Farther northeast, between the forks of Bear Creek, is a small area of dacite, which was regarded as an andesite in the field, but Dr. Patton finally relegated it to the dacites. The regularity of the hill gave rise to the expectation that it would be found to be a cinder cone, but this is not the case, as it is composed of solid dacitic lava. Its sides are covered with lapilli of pumice, like that found elsewhere, and upon the south bear a fine growth of yellow pine. There are a number of other hills farther north which appear to be composed of the same material.

GROUSE HILL DACITE FLOW.

Possibly of about the same relative age is the Grouse Hill flow, which crosses the crest a short distance northeast of Llao Rock. On the inner slope the layer of pumice beneath the great flow of Llao Rock overlaps the Grouse Hill flow, showing that the Grouse Hill flow is older than the Llao Rock eruption. For this reason the two flows are separated on the map. At the south base of Grouse Hill the dacite (107) is regularly banded, and on the hill next northeast of Llao Rock it (108) is spherulitic. This flow has been much eroded, and has a more ancient look than other flows of this portion of the rim.

LLAO ROCK DACITE FLOW.

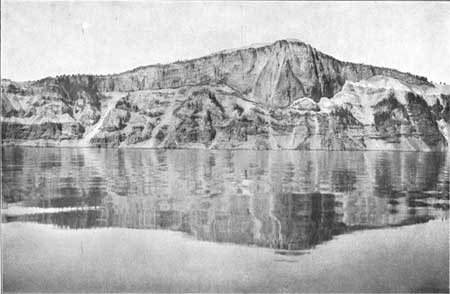

The Llao Rock flow is one of the most interesting of the region and is the most conspicuous. Its general outline in cross section filling a valley of the rim may be clearly seen (Pl. IX, A) across the lake. The flow is more than a mile wide along the crest and over 1,200 feet thick in the middle, tapering to edges on both sides. Considering its great thickness the flow is remarkably short, for it can be traced with certainty only about a mile from the rim, although it may extend for some distance farther beneath the pumice-covered plain. On the northeast it tapers rapidly to an edge, and ends in a mass of pumice nearly 100 feet thick. The lower portion of this pumice is clearly stratified, but in the upper part the lines are less distinct. The valley filled by the flow is small and has an irregular surface. On the northeast side there is a prominent mass of pumice (Pl. IX, A), under the Llao Rock flow, but on the opposite side there is little or no pumice. On the summit of Llao Rock there is much pumice. On the western slope it has been largely swept away, exposing the underlying rock. The edge of the flow, and, in fact, the entire periphery, is practically obsidian; the interior portion is more crystalline. Where glassy it is rich in small feldspars (102). On the summit, which has suffered much from erosion, a portion of the flow (103), originally some distance beneath the surface, is exposed, and on this account the rock is on the whole less glassy than near the border.

Plate IX—A. LLAO ROCK.

Plate IX—B. FLOW OF TUFFACEOUS DACITE EAST OF PUMICE POINT.

An imperfect columnar structure is given to the dacite of Llao Rock by two sets of joints. One set is radial from the lake and perpendicular to the rim; the other set crosses the first nearly at right angles. They are best developed in the lower portion of the flow. Near the surface a curved structure due to flowing is marked. Below, the flow structure is straight and nearly horizontal.

WINEGLASS DACITE FLOW.

The Wineglass flow is of small size and peculiar. lt lies in the next gap of the rim southeast of Round Top (Pl. VII, B), has a width of scarcely 500 feet, a length of probably a mile and a thickness of about 20 feet. It is decidedly like a tuff (114) and might well be so considered were it not for the stringers of black glass intermingled with a reddish groundmass containing fragments of other material and imparting a decided fluidal structure to the mass.

A short distance farther east there is another small sheet of this tuffaceous dacite 10 feet thick. It has the characteristic streaks of black glass which fix its identity. It occurs locally along the western edge of the Cloud Cap flow, and closely resembles much of the tuffaceous material of Redcloud Cliff. At the Wineglass slide it is immediately associated with pumiceous tuff. The hard rock of the rim is andesite, overlain by 15 feet of pumiceous tuff with 10 feet of red tuffaceous dacite. This is overlain by 30 feet of conglomerate and capped by a fine layer of pumice 25 feet thick. It is evident from this section that the fragmental dacite does not represent the final eruption, for that finds expression in the top layer of pumice.

The gap west of Round Top contains a small sheet of tuffaceous dacite like that on the other side, but is thicker. lt appears in Pl. VII, B, at the left of the Palisade crowned by Round Top. It is 50 feet thick in the middle and tapers to a thin edge on the west. On the east of Round Top it extends up the slope a short distance, for it is clearly seen above glacial striae and is undoubtedly a post-Glacial flow. In this gap, as upon the east, it overlies a sheet of pumice and underlies conglomerate into which it appears to pass by becoming more fragmental. Near the western edge of the gap it appears to be overlain by large bowlders, and where the exposure of the dacite ceases the sheet of large bowlders becomes more marked. On the geological map this area of dacite adjoins the edge of the great flow of Rugged Crest. In reality, however, it overlaps the Rugged Crest flow and is of later date.

The same tuffaceous dacite occurs farther west along the crest beyond Cleetwood Cove, where, as upon the east, it overlaps the flow of Rugged Crest. It extends nearly to Pumice Point (Pl. IX, B), where it appears between two thick masses of pumice. This peculiar tuffaceous dacite occurring along much of the northern crest of the rim all belongs to one flow, which spread as a uniformly thin sheet over that portion of the base of Mount Mazama. It is altogether unlike the other flows of dacite and appears to be intermediate between them and tuff.

CLEETWOOD COVE DACITE FLOW.

Among the final flows of the great volcano is the one of Cleetwood Cove. The rim at this point is remarkable. It is unlike any other portion of the rim in its rugged roughness without being sharp edged like Castle Crest. It is wooded with small pines and firs, but the bold crags stand out among them in pinnacled relief. The lava is a black, yellow, or brown glass, and is greatly broken and rough on the top. It forms the crest of the rim for nearly a mile, extending upon both sides of Cleetwood Cove, where it makes prominent cliffs. It fills an old valley at the head of the cove, and has a thickness of over 300 feet in the middle, tapering to a thin edge on both sides. Pl. X, B, illustrates its appearance from the lake. This broad flow extends from the rim northeastward for nearly 3 miles, where it disappears beneath the plain of pumice and glacial material. The bottom of andesite on which the dacite rests is irregular, and in places the two rocks are separated by a thick layer of pumice.

Plate X.—A. VALLEY OF CAVED-IN TUNNEL.

Plate X.—B. CLEETWOOD COVE FLOW.

On tracing the rugged mass of dacite away from the lake there is found upon its surface a small valley (Pl. X, A) lined with cliffs and local columns. The valley is nearly as deep as wide. Huge blocks of dacite have tumbled about in the most irregular manner, producing small inclosed basins. The valley is not a waterway, and judging from its peculiarities it is altogether probable that it is a caved-in lava tunnel.

Upon both sides of the surface the dacite is flattish and looks glaciated, yet no certain glacial marks could be found, although large fragments regarded as bowlders were seen resting upon it. West of the chaotic channel and also on the east above the cliff there appears to be some morainic material. Close to the crest at the head of Cleetwood Cove the surface is most broken and rugged. A little farther west the flow thins rapidly, forming West Deer Cliff, and runs out near the next point.

The upper portion of the sides of Cleetwood Cove is a cliff of dacite, beneath which there is a layer of pumice, succeeded downward by 350 or more feet of exposed andesitic flows. These subdacite lavas are continuous around the head of the cove, but are not exposed. At the head of the cove they are covered by dacite which flowed down the inner slope of the rim from the caved-in tunnel of Rugged Crest to the lake.

The flow is wide above and narrow below, lapping down over the edges of the andesite into the lake. How far it extends beneath the surface of the lake is unknown, but apparently only a short distance.

Some distance above the lake, upon both sides, the flow and platy structure of the dacite overlying andesite dip toward the central stream, which in places dips toward the lake at an angle of 35° and lies parallel to the present surface. The structure inclined toward the lake is very clear, and its parallelism to the surface underneath well exposed upon both sides. Near the summit the glassy rock (111) is red and black, and may be mixed with gray. Nearly midway from summit to lake, where the slope is steepest, the lava (112) is somewhat less glassy than near the crest, and near the lake (113) the crystalline structure is still more marked.

DACITIC DIKES.

Only two of the eleven dikes of Mount Mazama are dacite. They cut the older andesites (57) and connect directly with the thickest part of the Llao Rock flow. One of the dikes has a thickness of 10 feet. In the middle (130) it is holocrystalline and contains crystals of hornblende, but upon the border it is black and glassy, a vitrophyre (131), like most of Llao Rock. The other dike is regular, varying from 2-1/2 to 4 feet, and the material closely resembles the last in all respects. One of these, or possibly both, contributed to the escape of the great mass of Llao Rock.

DACITIC PUMICE.

The dacitic eruptions of Mount Mazama were generally accompanied by more or less pumice. Pl. IX, A, shows a large amount of pumice which underlies the Llao Rock dacite and which is, therefore, somewhat older than that flow. It is arranged in layers, probably due to the assorting influence of the atmosphere. Under the main body of the flow the sheet of pumice is sometimes wanting or thin and irregular. It is possible that this pumice belongs to the earlier part of the eruption which gave rise to Llao Rock.

The summit of Llao Rock is composed of fragmental material, approximately 120 feet in thickness, of which the lower 90 feet is pumice resting on the surface of the dacite. It is clear that this body of pumice is later than the Llao Rock flow, although it may belong to the final portion of the same eruption. The layer of white, pinkish, or yellowish pumice of the ordinary dacitic type (136) on the summit of Llao Rock is overlain by 20 feet of more or less pumiceous material, which is heavier and much darker in color. The fragments, like those of the layer below, are small, being rarely as large as 6 inches in diameter. Some of them (143) are black, rich in phenocrysts of hornblende and feldspar, and are doubtfully of a dacitic nature. There can be no question that the darker layer represents the concluding stage of the final explosive eruption of Mount Mazama. It is one of the largest masses of this sort of material found anywhere about the rim crest, and is of unusual importance on account of its peculiarities, for it is markedly unlike any of the dacitic lavas.

Along the crest above Danger Bay, near Sentinel Rock, there is a succession of pumice and glacial deposits. There are two deposits of what appear to be glacial gravels succeeded by layers of very pumiceous material, recording the fact of alternating glaciation and volcanic eruption. The lapilli of the two pumice layers appear to be the same. Farther to the northwest, beyond Cloud Cap, a thin sheet of tuffaceous dacite appears at the top of the lower pumice.

Tuff with much pumiceous fragmental material is widespread in the Crater Lake region, and is so abundant in places as to indicate a great explosive eruption along the final events in the history of Mount Mazama. Pumice Desert is a treeless tract north of the rim, in which pumice prevails. Fragments are usually from 1 to 4 inches through, although some nearly a foot in diameter are common in places, and occasionally larger ones appear. The largest mass of dacite seen (138) is 10 feet in diameter. It is very pumiceous and yet distinctly fragmental. Near by was a fragment 3 feet in diameter, rich in hornblende. Such fragments are not abundant, although black sand (134) composed chiefly of feldspar and hornblende is abundant everywhere. Here and there may be seen occasional chunks of andesite. From Mount Thielsen to Red Cone, a distance of over 10 miles, nothing but fragmental material was seen near the trail. As Red Cone is approached some of the red and black lapilli washed from the cone appear upon the surface to overlie the dacitic pumice and tend to give a wrong impression as to their order of eruption. The sheet of pumice, although not indicated upon the map, covers by far the larger part of the flows, but ledges are in general sufficiently numerous to determine approximately the distribution of the various kinds of lava. Along the southern border of the rim the greatest thickness of pumice, about 10 feet, is exposed at the top of Dutton Cliff. The largest fragments at that place are not more than a few inches in diameter and appear to be the farthest from the rim. The peculiar black lapilli rich in crystals of hornblende are numerous. Specimen 142 was collected from a piece 18 inches in diameter. Near the same place, in 1883, I found a bowlder-like bomb of the same size as that noted above. It had a blackened shell which was cracked to a little depth, and the cracks stood open like those of a bursted apple. The outside was very hard and glistened (148) as if melted and glazed. Within the rock was very porous and pumiceous (147). Near by another specimen had a thin, reddish, cracked rind with a more crystalline granitic center. Specimens 150 and 151 also were found along the northern rim of the lake and belong to this peculiar ejectamenta.

On the broad divide north of Crater Peak is a moraine composed largely of andesitic material. It is covered with dacitic pumice in such a way as to mark the relative age of the glaciation and eruption.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/3/part1-3c.htm

Last Updated: 07-Mar-2006