|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 58

The Guadalupian Fauna |

INTRODUCTION

THE GUADALUPIAN FAUNA.

By GEORGE H. GIRTY.

The first descriptions of the Guadalupian fauna were published nearly fifty years ago. This early account of Shumard's was meager enough, but gave promise of a facies interesting and novel among the known Carboniferous faunas of North America. The following pages add largely to our knowledge of Guadalupian life, and I believe more than make good any promise contained in the previous account. Nevertheless, even the collections of the Guadalupian fauna here described fail to do justice to its richness and diversity, and the present report is completed with the hope of returning to the subject after another visit to the Guadalupe Mountains.

Although a description of this range and the adjacent region can be found elsewhere, a repetition of the more important facts will conduce to a better understanding of the geologic relations of the fauna described herein and will serve to illustrate the references to localities and horizons necessarily involved in the paleontologic discussion.

The Guadalupe Mountains are situated chiefly in southeastern New Mexico, but extend across the border for a short distance into the trans-Pecos region of Texas. Save only for this southern extreme both their geology and their topography are practically unknown, and it should be understood that anything hereafter said of them relates only to that portion.

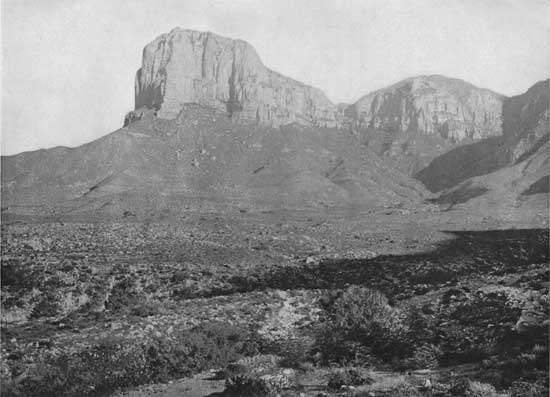

These mountains form a north-south range of considerable height, which rises abruptly from an arid and treeless plain, stretching westward to more mountainous elevations, the Cornudas Mountains and the Sierra Tinaja Pinta. This plain is locally known as Crow Flats and forms a part of the Salt Basin (Pl. I). It is now used as cattle ranges, water being raised by windmills. The only permanent surface water consists of salt lakes—broad, shallow pools incrusted with saline deposits, which in the early days were extensively sought for domestic use. This water is of course unfit for consumption, but cattle seem as a rule not to mind the less highly impregnated waters brought up by the pumps. These vary considerably in the amount and character of their saline contents, but even the best is unsatisfactory for human use.

|

| PLATE I. MAP OF SALT BASIN AND PARTS OF THE BOUNDING RANGES (click on image for a PDF version) |

On the east side, from the foot of the mountains the land slopes gradually eastward and merges with the plains of Texas. There are springs of sweet water and perennial streams on this side of the range, such streams being in this region, as a rule, associated only with the highest mountains. Usually the canyons and sandy channels serve merely to carry off the occasional torrential rains, and this is the case for the most part even with the perennial streams, which almost immediately on striking into the plain are drunk up by the soil. Beyond their debouchure from the mountains their course is merely a dry sandy channel. There are, however, flowing streams east of the Guadalupes, one such being Delaware River. In seasons of rain this watercourse is formed by the confluence of numerous small tributaries—some leading back into the mountains—which pour their sudden waters through channels usually dry; but the source of the perennial stream seems to be a very definite point situated some distance east of the Guadalupes and generally referred to as the "headwaters of the Delaware." This expression would naturally be taken to have a more general significance, but Shumard uses it, I believe, in this local sense, and as it is often difficult to fix references to local geography it seems desirable to make the present record of the fact. At this point, which is also known as Huhling's ranch, three springs, one of them strongly charged with sulphur, break out close together in the bed of the Delaware, which below this point is a permanent watercourse.

The Guadalupe Mountains are formed by uplifted strata, consisting of a thick limestone series above and a thick sandstone series below. The abrupt termination of the limestone in an almost sheer precipice of practically its entire thickness not far south of the New Mexico border marks the termination of the formation and of the Guadalupe Mountains proper. The sandstone, however, continues southward, forming a westward-facing escarpment, which with the adjacent foothills and outliers is known as the Delaware Mountains.

The southern branch of the old Santa Fe trail passed up Delaware River and close around the base of Guadalupe Point, as the abrupt, precipitous termination of the range is commonly designated. The ruined walls of a blockhouse situated near the mouth of Pine Spring Canyon bear witness to the days when a stage route passed this way. Now, however, the trail has been long unused, and heavy washouts have rendered it in places impassable, so that a traveler approaching from the west would be compelled to make a considerable detour to the south if, as in our own case, he was necessarily hampered by wagons. After again coming nearly abreast of Guadalupe Point the road passes up Guadalupe Canyon (Pl. II), which penetrates the mountains in a direction nearly north and south and contains toward its head a little spring called Guadalupe Spring. Before reaching the spring, however, the trail turns to the east and, rising to the level of the plateau by a short though steep ascent, extends northward past the ruined caravansary which stands at the mouth of Pine Spring Canyon. This canyon is situated almost on the flank of El Capitan, the spur which bounds it on the south forming the most satisfactory if not the only avenue of ascent to that peak. Near this spring was the site once, probably in the old staging days, of an encampment of regulars, evidences of whose occupancy are not rare—a brass button or an empty cartridge being the least frequently found. Nearly every adjacent peak is surmounted by a cairn, probably raised by their hands, while on an eminence near by, from which a sweeping view can be had across the eastward plain, a number of small tumuli, containing, it is said, only ashes, appear to mark the stands of outposts or sentries. A hint of the occasion for the presence of troops at this point is furnished by a stone erected beside the road in Guadalupe Canyon, which bears a date somewhere in the early sixties, I believe, and above two crossed arrows an inscription commemorating the death of a Mexican guide at the hands of Indians.

|

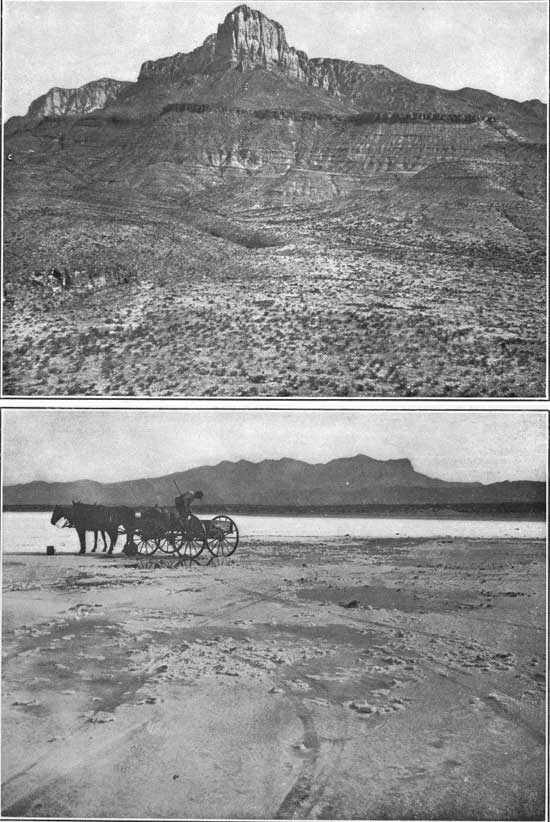

| PLATE II. GUADALUPE POINT, EAST SIDE, VIEW NORTH UP GUADALUPE CANYON. The massive crag exposes 1,200 feet of the Capitan formation; the softer beds below are the Delaware Mountain formation. (From a photograph by R. T. Hill.) |

The party to which I belonged camped at Pine Spring, and during the eleven days of our stay were made the different trips that furnished the collections on which the present report is principally based. The other collections from the Guadalupe Mountains included in this report are comparatively unimportant, but, on the other hand, I am entirely indebted to my colleagues for valuable collections from other areas.

In view of the highly fossiliferous character of some of the strata, our collections, though considerable, are less extensive than would be expected if the fruits of eleven days' work in some other fields were used as a standard. Owing to the height and steepness of the mountains themselves and the broken character of the country at their base, it is in many places no easy matter to reach points comparatively near by, and it will probably be necessary for those who purpose to visit the Guadalupe Mountains with the intention of collecting fossils to calculate on expending more than the usual time and labor.

The lowest beds in the Guadalupe section are limestones, very black in color and formed in rather thin and even beds. These are exposed in some dry canyons south of Guadalupe Point to a thickness of perhaps 200 feet, the base not being seen. These limestones are succeeded by a heavy series of variable beds, chiefly of sandstone. There are also strata of calcareous sandstone, of dark shale, and of dark- and light-colored limestone. The conditions of deposition appear to have been fluctuating, not only vertically but laterally, prominent beds of sandstone seen in cliff sections dying out and appearing with rather remarkable abruptness. Including the black limestone, this portion of the section was found by Richardson to attain a thickness of about 2,225 feet, and he gave it the name Delaware Mountain formation. A bed of dark limestone above the sandstones and below the white limestone deserves especial mention because of references in the literature to it and because of the distinctive fauna which it contains. The succeeding formation, called by Richardson the Capitan limestone, consists of massive limestone measuring about 1,800 feet in thickness. The color of these beds is in general white, but they are in places tinged with red and yellow. Much of the rock is a pure limestone, but at least one considerable stratum is dolomitic, having the structure of pisolite; and other beds, especially. in the lower part, have a sandy texture, which may be due to the same cause.

The Guadalupe Mountains are a structural range with a precipitous western escarpment which has been ascribed to faulting, but which at its southern extremity, as Richardson has shown, can be explained as an unsymmetrical broken fold. At all events, in the main range the beds dip to the east at a rather high angle, their abrupt termination on the west forming the mountain's side in that direction. It must not be thought, however, that the Guadalupe Mountains are, like the Delawares, really a plateau with a gradual descent toward the Pecos from a level near the top of the Capitan limestone. On the contrary, the eastern slopes are difficult and rugged. Erosion in this direction has cut away the Capitan and part of the Delaware Mountain formation, and the present surface of the plateau at Guadalupe Pass is formed, locally at least, by a bed of limestone, such as has already been mentioned, occurring about two-thirds of the way up in the Delaware Mountain formation.

In its eastern spread the Capitan limestone has been limited by erosion, and probably owing to the same cause its southern extension abruptly terminates in a bare and lofty crag. Mounted as it is upon the entire thickness of the Delaware Mountain formation, this bold headland has an appearance singularly monumental. It is known pretty generally as Guadalupe Point or Guadalupe Peak. Although the most imposing, this is not the highest point of the range, for just beyond it to the north rises another which overlooks it. This peak has been called El Capitan, and I have, when called on to refer to it, retained this name, which is further perpetuated in the Capitan limestone (Pls. II, III).

|

| PLATE III. A (top), GUADALUPE POINT FROM A GREATER DISTANCE AND MORE DIRECTLY FROM THE SOUTH. The Delaware Mountain formation is well shown underlying the massive Capitan limestone. (From a photograp by G. B. Richardson.) B (bottom), GUADALUPE MOUNTAINS FROM THE WEST. In the foreground are the salt deposits of the Salt Basin, from which rises the bold profile of the range. At the right is the precipitou front of the Guadalupe Point, and back of it the loftier summit of El Capitan. (From a photograph by G. B. Richardson.) |

Owing to the conditions of structure and erosion above described, the general level on the west side of the fold and fault, where the streams show several hundred feet of the basal black limestone, is lower than on the east, where erosion has cut down only part way through the overlying sandstones. While the Capitan limestone terminates precipitously at Guadalupe Point, these sandstones continue in a long southward extension, their westward-facing escarpment being known as the Delaware Mountains, from which circumstance they have received the name of the Delaware Mountain formation. West of the Delawares and some distance south of Guadalupe Point rise the Diablo Mountains, formed by an elevated block of the Hueco formation, to which reference will be made later.

The first accounts of the geology and paleontology of the Guadalupe Mountains were published by the two Shumards in 1859 and 1860.a As geologist of the expedition under Captain Pope, dispatched to discover artesian waters in the arid lands of the Southwest, George G. Shumard obtained some collections of fossils from the south end of the Guadalupes, which were subsequently described by his brother. Shumard does not give a clear account of the structure of the Guadalupe Mountains, but his section is as follows: b

Section of Guadalupe Mountains (Shumard).

| Feet. | |

| 1. Upper or white limestone | 1,000 |

| 2. Dark-colored, thinly laminated, and foliated limestone | 50-100 |

| 3. Yellow quartzose sandstone | 1,200-1,500 |

| 4. Black, thin-bedded limestone | 500 |

aTrans. St. Louis Acad. Sci., vol. 1, 1856-1860, pp. 273-297, 387-403.

b Idem, p. 280.

The sequence of the formations in this region is obvious and in the more recent accounts remains practically as described by Shumard, although more accurate measurements have since been made, the upper limestone and the sandstone proving to be even thicker than indicated by him, while no subsequent observer has reported so much of the basal black limestone. Fossils were obtained from the three upper members of Shumard's section, those from the two limestones being later described by B. F. Shumard and proving to have each a rather distinct facies. The two formations were distinguished in the paleontologic account as the "dark limestone" (bed 2) and the "white limestone" (bed 1). Apparently the "white limestone," the "dark limestone," and the sandstone were regarded by Shumard as belonging in the Permian.

For many years after Pope's expedition this immediate region does not figure in geologic literature, although one of the main routes of travel, the Santa Fe trail, passed around Guadalupe Point.

The next observer on record is R. S. Tarr, who in 1892 published a paper in which he describes the geology of the southern part of the Guadalupes.a This author gives the following section as measured at the point of the mountains (Guadalupe Point): b

Section at Guadalupe Point (Tarr).

| Feet. | |

| 1. Upper or white limestone | 1,200-1,500 |

| 2. Dark-colored limestone | 50 |

| 3. Yellow clayey sandstone, with numerous bands of black and white limestone | 1,200 |

| 4. Black limestone, shale, and slate | 200 |

aBull Geol. Survey Texas No. 3, 1892, pp. 9-39.

bIdem, p. 29.

A detailed section partly through the white limestone at McKitterick Canyon is also given by Tarr. He clearly states the monoclinal structure of the range and describes its precipitous western scarp as probably due to faulting. His tentative conclusions regarding the correlation of the Guadalupian section with that of central Texas is supported by too little and opposed by too much evidence to warrant adoption. He found that there was nothing in the Guadalupian section to correspond lithologically with the Permian ("Red Beds") of Texas, and concluded that the Guadalupian section lay below the Permian and was probably of the age of the "Upper Coal Measures" of Texas and the Mississippi Valley. In view of the completely different fauna of the Guadalupian, this question must still be regarded as unsettled.

Some time later R. T. Hill visited this region, but he has not yet published an account of his observations. The year following (1901) B. F. Hill and I made a trip as nearly as possible over Shumard's old route, but from the west eastward, and therefore in an opposite direction. The present work is a final report of that trip, being an amplification of the short paper which I wrote at that time on the geology and paleontology of the Guadalupes.c Meanwhile G. B. Richardson has made a general reconnaissance of the Guadalupe Mountains and adjacent regions, and to his accounta the reader should refer for more authoritative information regarding points here only lightly touched.

cAm. Jour. Sci., 4th ser., vol. 14, 1902, pp. 363-368.

aBull. Univ. Texas Min. Survey No. 9, November, 1904, 119 pp., 11 pls.

In my brochure of 1902 the thickness of the upper limestone, including Shumard's "dark limestone," was given at 1,700 to 1,800 feet, that of the underlying sandstone as 2,000 to 2,500 feet, and that of the basal black limestone as 500 feet exposed. The chief point made was in relation to the faunas, which were shown to be very different from anything known elsewhere in America. On this account "Guadalupian" was introduced as a regional term, provisionally to include the entire rock series exposed near Guadalupe Point, but more specifically centering about the upper portion, the white and the dark limestones. Note was also made of the resemblance of the Guadalupian fauna to certain faunas of Asia and Europe.

Although Richardson made only a reconnaissance, his report on the region under consideration is the most accurate and complete which we yet have, for the formations were described and mapped over an extensive area. The highest member of the series he named the Capitan limestone and the underlying beds the Delaware Mountain formation. The latter name includes both Shumard's "dark limestone," the great sandstone series, and the basal black limestone. Richardson states that in view of the small extent of the black limestone in the area mapped (it is exposed only in the immediate vicinity of Guadalupe Point), it was thought best for the time being to regard it as a member of the Delaware Mountain formation rather than as a distinct formation. The fauna of this bed, however, at present appears to have a rather distinctive facies and is kept separate in this report. With somewhat less reason the upper limestone of the Delaware Mountain formation (Shumard's "dark limestone") has been distinguished from the main body of the formation, which in the vicinity of Guadalupe Point consists chiefly of sandstone. The fauna of this upper limestone appears to have a rather well-marked facies, while lithologically in this immediate region the limestone is distinguishable both from the sandstone below and from the Capitan limestone above. Furthermore, for the purpose of correlating my horizons with Shumard's, it is desirable to recognize this zone; and it is as yet a little uncertain whether the fauna is more closely related to that of the Capitan or that of the Delaware Mountain sandstone. Accordingly, in the Guadalupian section I distinguish the basal black limestone, the Delaware Mountain formation, the "dark limestone," and the Capitan limestone, all but the last being comprised in the original Delaware Mountain formation. The basal black limestone, however, is not known to occur elsewhere than in the vicinity of Guadalupe Point, while in the southern Delawares the "dark limestone" can not be recognized as a separate member. In this connection I may recall that Richardson's observations indicate that, whereas in the vicinity of Guadalupe Point the sandstones greatly predominate in the Delaware Mountain formation, these rocks become largely replaced by gray limestones to the south.

In point of thickness Richardson found that only 200 feet of the basal black limestone are exposed. At its greatest exposure the Delaware Mountain formation ranged to about 2,300 feet, but its base was there concealed by the Salt Basin deposits. At Guadalupe Point he measured 2,025 feet exclusive of the basal black limestone. The Capitan limestone he gives at 1,700± feet at the scarp of Guadalupe Point; our own measurement was 1,800 feet to the top of the still higher peak, El Capitan (Pl. III).

As to structure, Richardson's conclusions seem to be that the uplift was a fold in the southern part of the field visited by him, passing into a fault in the northern part, the zone of transition apparently occurring in the vicinity of Guadalupe Point.

Since the scheme of mapping employed by the Survey demands that the Guadalupian series be called categorically either "Permian" or "Pennsylvanian," it seemed best to refer it to the Permian, because of the very different and at the same time younger facies of the faunas, even that of the basal black limestone, as compared with the Pennsylvanian of the Mississippi Valley region, and because the underlying Hueco formation has a fauna more nearly comparable to that of the Russian Gschelstufe, which underlies the Russian Artinsk and Permian.

Neither Richardson nor any other observer has determined what immediately precedes or immediately follows the Guadalupian series, and this remains one of the important problems awaiting investigation in this region. It is true, Tarr says that above the massive limestone is another series of limestones and sandstones which are found only on the highest points in Texas, but which farther to the north, in New Mexico, are well developed and form the bulk of the mountains. He made no section of these beds, but states that they can not be less than 1,000 feet in thickness,a and again: "The total section exposed in the Guadalupes, approximately stated, can not be less than 4,000 feet, including the New Mexico series, which exist above the white limestone."a I do not know what rocks are intended by this indefinite statement. The Capitan limestone is not known in Texas, so far as I am aware, save in the Guadalupe Mountains and the foothills adjacent, where no overlying series is exposed. It must of necessity extend northward into New Mexico, unless faulted out, but all our faunas from New Mexico, so far as I have examined them, show an altogether different facies, one more suggestive of the beds which there is every reason to believe really lie below the Guadalupian.

aBull. Geol. Survey Texas No. 3, 1892, p. 31.

The formation underlying the Guadalupian is the Hueco. The typical exposures of this formation are in the Hueco Mountains and the higher beds are uplifted to the east in the Cornudas Mountains and the Sierra Tinaja Pinta. Still farther east the Hueco beds are concealed by the Salt Basin deposits, and in the Guadalupe Mountains we have an altogether different series, even the basal member of the Guadalupian having a fauna widely different from that in any zone of the Hueconian. The structure in the vicinity of the Guadalupe Mountains, the stratigraphic relations of the Hueco beds with underlying formations, and the biological character and relations of the Guadalupian fauna all point to the position of the Guadalupian series as overlying the Hueco formation. By how large an interval the highest known exposures of the Hueco are separated from the lowest known exposures of the Guadalupian can not be told, but at present it is not supposed to be great.

We owe our first account of the Guadalupian fauna to B. F. Shumard, one or two of the bryozoan forms having, however, been turned over for description to Prout.

The following table shows the species cited by Shumard and the names under which they appear in the present report:

Fossils from Guadalupe Mountains described by B. F. Shumard.

| Shumard's list.a | Equivalents in the present report. |

| Chaetetes mackrothii Geinitz | Undetermined, possibly Leiociema shumardi. |

| Chaetetes sp. ? | Undetermined, possibly Fistulipora grandis var. americana. |

| Campophyllum ? texanum n. sp | Campophyllum texanum? |

| Polycoelia ? | Lindstroemia permiana. |

| Phillipsia perannulata shumard | Anisopyge perannulata. |

| Bairdia sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Fenestella popeana Prout | Not recognized; see Fenestella popeana. |

| Acanthocladia americana Swallow | Probably Acanthocladia guadalupensis. |

| Fusulina elongata Shumard | Fusulina elongata. |

| Productus calhounianus Swallow | Undetermined; possibly Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis. |

| Productus mexicanus Shumard | Not recognized. |

| Productus pileolus Shumard | Productus ? pileolus. |

| Productus semireticulatus var. antiquatus Martin | Probably Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis. |

| Productus popei Shumard | Productus popei. |

| Productus norwoodi Swallow | Not recognized. |

| Productus leplayi ? Verneuil | Possibly Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis. |

| Strophalosia (Aulosteges) guadalupensis Shumard | Aulosteges guadalupensis. |

| Chonetes permiana n. sp | Chonetes permianus. |

| Chonetes flemingi ? Norwood and Pratten | Probably Chonetes hillanus. |

| Spirifer mexicanus Shumard | Spirifer mexicanus. |

| Spirifer guadalupensis n. sp | Squamularia guadalupensis. |

| Spirifer sulciferus Shumard | Not recognized; see Spirifer sulcifer. |

| Spirifer cameratus Morton | Spirifer sp. b. |

| Spiriferina billingsi Shumard | Spiriferina billingsi. |

| Terebratula elongata Schlotheim | Possibly Dielasma spatulatum. |

| Terebratula perinflata n. sp | Not recognized; see Dielasmina perinflata. |

| Rhynchonella guadalupae Shumard | Not recognized; see Rhynchonella guadalupae. |

| Rhynchonella indentata n. sp | Rhynchonella indentata. |

| Rhynchonella texana n. sp | Not recognized; see Rhynchonella texana. |

| Rhynchonella sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Camerophoria bisuicata Shumard | Pugnax bisulcata. |

| Camerophoria swalloviana n. sp | Pugnax swallowiana. |

| Camerophoria schlotheimi? Buch | Not recognized. |

| Retzia papillata Shumard | Hustedia papillata. |

| Retzia meekiana Shumard | Hustedia meekana. |

| Streptorhynchus (Orthisina) shumardianus Swallow | Not recognized. |

| Orthisina sp. ? | Probably Orthotetes guadalupensis. |

| Crania permiana n. sp | Richthofenia permiana. |

| Myalina squamosa Sow | Probably Myalina squamosa |

| Myalina recta Shumard | Not recognized. |

| Pleurophorus occidentalis Meek and Hayden | Not recognized. |

| Monotis speluncaria Schlotheim | Not recognized. |

| Monotis sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Axinus securus n. sp | Schizodus securus. |

| Edmondia semiorbiculata Swallow | Not recognized. |

| Cardiomorpha sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Turbo guadalupensis n. sp | Not recognized; see Turbo guadalupensis. |

| Turbo helicinus ? Schlotheim | Not recognized. |

| Straparollus sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Bellerophon sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Pleurotomaria halliana n. sp | Not recognized; see Euconospira halliana. |

| Chemnitzia swalloviana n. sp | Zygopleura swallowiana. |

| Nautilus sp. ? | Not recognized. |

| Orthoceras sp. ? | Not recognized. |

aTrans. Acad. Sci. St. Louis, vol. 1, 1859, p. 387.

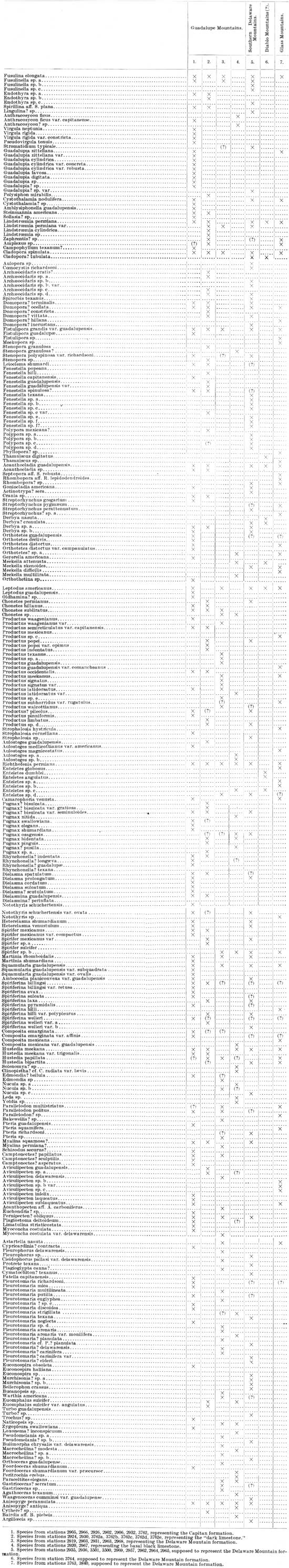

Shumard recognized 54 species among the fossils collected at that time, 26 of which were described as new. As based on recent collections made in the Guadalupe Mountains and adjacent regions the Guadalupian fauna now known contains 326 forms, and the resources of the fauna at present appear to be almost inexhaustible. Collections which did justice to its richness and importance would greatly enhance the number distinguished in this report. The 326 forms at present constituting the Guadalupian fauna belong to the different zoological groups in the following quotas.

Zoological groups represented in the Guadalupian fauna.

| Species. | Species. | ||

| Protozoa | 9 | Pelecypods | 45 |

| Sponges | 24 | Scaphopoda | 1 |

| Coelenterates | 10 | Amphineura | 1 |

| Echinoderms | 7 | Gasteropods | 42 |

| Vermes | 1 | Cephalopods | 9 |

| Bryozoa | 44 | Crustacea | 5 |

| Brachiopods | 128 | 326 |

As shown by this list the Guadalupian fauna manifests an unusually symmetrical development, for while it is true that the brachiopods predominate, the other groups also are represented in a proportion which is seldom equaled. It is also an extremely rich fauna, for it should be borne in mind that our collections are not exceedingly extensive. In few other regions would an equal amount of material have furnished so great a variety of species, a fact due in part no doubt to the unusual thickness of the Guadalupian section.

The Guadalupian species are mostly small as compared with those of other regions and with the average in the groups to which they belong. An exception, striking because of its isolation and degree, is found in Fusulina elongata, one of the most abundant and characteristic Guadalupian species and probably the largest Fusulina that science has yet brought to notice. Aside from this, the Foraminifera are rather poorly represented in comparison with some late Paleozoic faunas, though they are probably less completely studied than any of the other groups.

The sponges, if certain peculiar forms be allowed to remain under that designation, are, on the other hand, unusually abundant and varied, developing some novel and characteristic types of structure.

Coelenterates are more rare, small, and poorly differentiated. The absence of forms like Lonsdaleia, Michelinia, and the stromatoporoids, such as are found in some of the Asiatic faunas, is worthy of note, as is also the presence of Cladopora, which is a rather characteristic fossil of some of the lower beds. On the whole, however, the coelenterate fauna is rather meager and colorless.

Echinoderms are rare, the most noticeable being a new genus of cystidians. The presence of crinoid stems, however, shows that the true crinoids, such as occur in some of the related faunas, are present, though none of the heads have been found.

Except for one or two types the Bryozoa are rather scanty, and contain little that is striking or highly novel. The series of forms which I have assembled under Domopora is so important an exception to this statement, however, as almost to contradict it. These forms, which find their closest allies apparently in the Mesozoic, rather than in the Paleozoic, occur nowhere, so far as I have been able to discover, except in the trans-Pecos region. They form one of the most abundant and one of the most characteristic features of the Guadalupian bryozoan fauna. Acanthocladia guadalupensis is equally abundant but less peculiar.

Among the Brachiopoda, which demand a somewhat more detailed consideration than the other groups, the strophomenoids show an unusual generic differentiation, in which the presence of the rare genus Geyerella and of several species of Streptorhynchus is noteworthy. Orthotetes guadalupensis, a characteristic species of the Capitan, is likewise a unique type. The presence of Richthofenia and Leptodus also forms a novel and important feature of the Guadalupian fauna.

The Productidae, while fairly numerous, are not so highly differentiated as in many other faunas. We note the comparative absence of large species of the semireticulatus group, and the entire absence of the fimbriati, a group which includes such common forms as Productus punctatus, P. humboldti, or our own P. nebraskensis. No forms related to P. horridus of the European Permian have been brought to light, while the Marginifera group also appears to be wanting. There are a few singular types, such as P. limbatus, P. pileolus, etc., while the development in the "dark limestone" of a group of small, strongly arched shells with deep sinus, of the general type of P. semireticulatus, though with more or less faint ribs and wrinkles, may be mentioned; but as a rule the Chonetes and Producti do not stand out in strong relief. Aulosteges, however, is rather remarkably differentiated, though I have not found it in any abundance.

The Orthis group is rarely encountered. No other type is yet known than Enteletes, and with one exception the species all belong to the ventrisinuate group.

The dorsisinuati, which develop such peculiar species in the faunas of India and the Carnic Alps, are represented by only one imperfect specimen. In the upper beds of the Guadalupian (Capitan formation) this group appears to be absent.

Compared with some faunas the Pentameridae are poorly represented. To some extent this is true of the Rhynchonellidae also, since they present less variety, both in species and genera, than, for example, the Salt Range faunas. In the group of Pugnax bisulcata, however, the Guadalupian possesses a feature which is both characteristic and abundant. The absence of Uncinulus, Terebratuloidea, Rhynchopora, etc., may here be noted.

The Terebratulidae are highly differentiated and present at least one new generic type.

The Spiriferidae are represented by a number of genera, but show less variety in their specific representation. In the genus Spirifer especially we miss group after group which is found in faunas more or less related, the representation being restricted practically to Spirifer mexicanus and its allies. The Spiriferinas, on the contrary, show a high differentiation. Many of the species belong to the group of S. billingsi, which is rather characteristic of the Guadalupian. S. welleri is also a marked species.

The Athyridae and the Retziidae call for little comment. Like Ambocoelia, Composita is rather an American genus, though not exclusively so, and it is also rather abundant in the Guadalupian fauna, where it is represented by a novel and interesting type. The absence of Cleiothyridina is perhaps deserving of mention.

The remaining groups may be passed over with less comment, for while not meanly developed they show few peculiarities of note. Among the pelecypods a unique Guadalupian type is the group of species referred to the genus Camptonectes, which seems to have an analogue nowhere else in the Carboniferous, so far as I have discovered. The remainder of the Guadalupian pelecypods, while new in their specific characters, are more like the generality of Carboniferous faunas. The Pterias seem to be unusually differentiated, and we notice the absence or rarity of certain types common in many other Carboniferous faunas, such as the large Myalinas, the Edmondias, and the genus Pseudomonotis. Shumard, it is true, cites Monotis speluncaria in this fauna, but it is uncertain what form he actually had in hand, and in this, as in other instances, my comparisons are made exclusively with the collections which I have been able to study.

The gasteropods show few points of note. The development of the Pleurotomarias is perhaps a little extraordinary, as is the slight representation of the Bellerophons, which include, however, what is probably a representative of the Indian genus Warthia.

The Cephalopoda are evidently of the late Paleozoic type, but show less differentiation than might have been expected. Indications are not lacking, however, that at favored localities, which I was personally not fortunate enough to discover, the group is very plentiful, and that subsequent collections will show the Guadalupian Cephalopoda to have been highly differentiated.

The Crustacea are, with the exception of the trilobites, poorly represented. Decapods, which Gemmellaro found in some abundance in his Sicilian faunas, are unknown, and Ostracoda, which are apparently rather common in the Permian of Europe, are rare. The trilobites, not the least interesting section of this group, are however, fairly abundant, and show a construction which apparently is typical of a new genus.

The highest horizon at which Guadalupian fossils were obtained is the top of El Capitan, which by our barometric measurements is 1,800 feet above the base of the Capitan limestone. Here, from the summit and just below, I collected the following species (station 2905):

| Fusulina elongata. | Guadalupia cylindrica. |

| Fusulinella sp. a. | Guadalupia cylindrica var. robusta. |

| Endothyra sp. a? | Guadalupia? sp. |

| Spirillina aff. S. plana. | Cystothalamia nodulifera? |

| Virgula rigida? | Fenestella capitanensis. |

This fauna, it will be observed, consists almost exclusively of Protozoa and sponges. A considerable thickness of white limestone carrying the large Fusulina elongata so thickly packed and so uniformly laid down in one direction as almost to appear as if arranged by hand, is an interesting feature of this locality. At what appears to be the same point Richardson obtained the following (station 2966):

| Fusulina elongata. | Fenestella spinulosa? |

| Guadalupia cylindrica. | Acanthocladia guadalupensis? |

| Cystothalamia nodulifera. | Derbya sp. b. |

| Amblysiphonella guadalupensis. | Composita emarginata. |

| Sollasia? sp. | Rhynchonella guadalupae? |

| Domopora? ocellata? | Dielasma spatulatum? |

| Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis. | Notothyris schuchertensis var. ovata. |

| Fistulipora guadalupae. | Heterelasma shumardianum. |

| Stenopora polyspinosa var. richardsoni. | Pteria guadalupensis. |

| Leiociema shumardi? | Patella capitanensis. |

This fauna is more varied than that which I obtained, and has, consequently, more of the typical Capitan facies, but my own efforts at collecting were limited by stress of time to picking up a few specimens on the way down.

By far the best point which we found for collecting in the Capitan formation was halfway up Capitan Peak (station 2926), midway in the formation which bears its name. Here the fauna is extensive and varied, as shown by the following list of species collected by B. F. Hill and myself:

Anthracosycon ficus var. capitanense.

Virgula neptunia.

Virgula rigida.

Virgula rigida var. constricta.

Pseudovirgula tenuis.

Guadalupia zitteliana.

Guadalupia zitteliana var.

Guadalupia cylindrica.

Guadalupia cylindrica var. concreta.

Guadalupia favosa.

Cystothalamia? sp.

Steinmannia americana.

Sollasia? sp.

Lindstroemia permiana.

Campophyllum texanum?

Domopora? terminalis.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Leioclema shumardi?

Fenestella capitanensis.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia sp.

Goniocladia americana.

Crania sp.

Streptorhynchus gregarium.

Derbya sp. a.

Orthotetes guadalupensis.

Orthotetes declivis.

Orthotetes distortus.

Orthotetes distortus var. campanulatus.

Geyerella americana.

Orthothetina sp.

Chonetes hillanus.

Productus waagenianus.

Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis.

Productus occidentalis.

Productus latidorsatus.

Productus? pileolus.

Productus pinniformis.

Aulosteges medlicottianus var. americanus.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spirifer mexicanus.

Spirifer mexicanus var. compactus.

Martinia rhomboidalis.

Martinia shumardiana.

Squamularia guadalupensis.

Squamularia guadalupensis var. subquadrata.

Squamularia guadalupensis var. ovalis.

Ambocoelia planiconvexa var. guadalupensis.

Spiriferina billingsi.

Spiriferina billingsi var. retusa.

Spiriferina evax.

Spiriferina sulcata.

Spiriferina pyramidalis.

Spiriferina welleri.

Composita emarginata.

Composita emarginata var. affinis.

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia meekana var. trigonalis.

Pugnax? bisulcata var. seminuloides.

Pugnax swallowiana.

Pugnax elegans.

Pugnax shumardiana.

Rhynchonella indentata.

Rhynchonella longaeva.

Camarophoria venusta.

Dielasma spatulatum.

Dielasma cordatum.

Dielasma sulcatum.

Dielasma? scutulatum.

Dielasmina guadalupensis.

Notothyris schuchertensis.

Notothyris schuchertensis var. ovata.

Heterelasma shumardianum.

Heterelasma venustulum.

Leptodus guadalupensis.

Oldhamina? sp.

Edmondia? bellula.

Parallelodon multistriatus?

Parallelodon politus.

Pteria guadalupensis.

Myalina squamosa?

Schizodus securus?

Camptonectes? papillatus.

Camptonectes? sculptilis.

Camptonectes? asperatus.

Aviculipecten infelix.

Aviculipecten laqueatus.

Aviculipecten sublaqueatus?

Euchondria? sp.

Pernipecten obliquus.

Plagiostoma deltoideum.

Limatulina striaticostata.

Myoconcha costulata.

Cypricardinia? contracta.

Pleurotomaria mica.

Pleurotomaria putilla.

Pleurotomaria discoidea.

Pleurotomaria neglecta.

Euconispira obsoleta.

Trochus? sp.

Zygopleura swallowiana.

Foordoceras shumardianum.

Anisopyge perannulata.

This may be regarded as the typical Capitan fauna, and the fact that in so short a time and in relatively so small an amount of material we were able to obtain over a hundred species attests the richness and variety of life during the Capitan epoch.

About the same horizon, or one a little higher, was visited on the peak above Pine Spring, on the north side of Pine Spring Canyon, but this locality (station 2902) did not prove fruitful. I obtained only the following species:

| Virgula neptunia? | Guadalupia digitata. |

| Virgula rigida? | Guadalupia sp. |

| Guadalupia cylindrica. | Ambocoelia planiconvexa var. guadalupensis. |

The facies of this fauna recalls that obtained at the top of El Capitan (station 2905).

The lower beds of the Capitan furnished fossils from two widely separated stations. One of these is the hill southwest of Guadalupe Point (station 2906), where a detached block of the Capitan limestone is faulted to a much lower level than that on the crest of the range. At this locality fossils are plentiful, but their preservation is poor, as the rock appears to be more or less altered and many of the specimens are crushed or distorted. The fauna obtained here, which comes from immediately above the "dark limestone," has almost identically the facies of the middle portion. In the brief time at my disposal I obtained the species named below:

Amplexus sp. ?

Cladopora spinulata.

Domopora terminalis.

Domopora ocellata.

Leioclema shumardi.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Derbya sp.a.

Orthotetes guadalupensis.

Orthotetes declivis.

Chonetes subliratus.

Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis.

Strophalosia cornelliana.

Spirifer mexicanus.

Martinia rhomboidalis.

Martinia shumardiana?

Squamularia guadalupensis.

Squamularia guadalupensis var. ovalis.

Spiriferina evax.

Spiriferina welleri.

Composita emarginata.

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia meekana var. trigonalis.

Hustedia papillata?

Pugnax elegans.

Rhynchonella longaeva?

Leptodus americanus.

Aviculipecten sublaqueatus.

Pleurotomaria? sp. C.

Anisopyge perannulata.

The other point at which fossils were obtained from the lower Capitan was in McKitterick Canyon (station 2932). The rock, a dense white limestone, lies conveniently at stream level, and the horizon appears to be in the lower part of the formation. Fossils proved scarce, and almost no time could be given to the search for them, so that I obtained only two species—Spiriferina sulcata? and Dielasma prolongatum.

The character and status of Shumard's "dark limestone" are somewhat uncertain to me. The cliff at Guadalupe Point contains at its base an undetermined thicknessa of dark limestone, which was presumably the bed referred to by him, but the precipice was too abrupt to scale and no fossils were obtained. Again, on the hill southwest of Guadalupe Point, beneath a whitish limestone (station 2906) having the lithology of the Capitan and a fauna closely related to that collected from the middle of the formation (station 2926) occurs a not very thick series of dark limestones (station 2924), which are also supposed to represent the "dark limestone" of Shumard. I obtained here the following forms:

Fusulina elongata.

Cladopora spinulata.

Domopora? terminalis.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Fenestella sp. c. var.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Productus popei?

Spirifer mexicanus var.

Hustedia meekana.

aFifty feet, according to Richardson.

On both occasions when we ascended Capitan Peak, as nearly as possible the same route being selected, the contact between the Capitan and Delaware Mountain formations was concealed by talus. My notes contain no reference to the rocks of this horizon in the vicinity of Pine Spring, but from loose blocks on the north side of the canyon (station 2930) I collected a considerable amount of material which probably belongs to the "dark limestone." The following list represents the fauna obtained from this source:

Fusulina elongata.

Endothyra sp. a.

Endothyra sp. b.

Spirillina aff. S. plana.

Polysiphon mirabilis.

Steinmannia americana.

Lindstroemia permiana.

Lindstroemia permiana var.

Lindstroemia cylindrica.

Lindstroemia sp.

Cladopora spinulata.

Archaeocidaris sp. c.

Archaeocidaris sp. d.

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora ? ocellata.

Domopora? constricta.

Domopora? vittata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Stenopora granulosa.

Stenopora sp.

Leioclema shumardi.

Fenestella guadalupensis.

Fenestella guadalupensis var.

Fenestella spinulosa?

Polypora mexicana?

Polypora sp. C?

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia sp.

Crania sp.

Derbya sp. a.

Chonetes permianus.

Chonetes hillanus.

Chonetes subliratus.

Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis.

Productus popei.

Productus popei var. opimus.

Productus indentatus.

Productus occidentalis.

Productus? pileolus?

Productus limbatus.

Productus sp. d.

Aulosteges guadalupensis.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spirifer mexicanus.

Spirifer mexicanus var.

Spirifer sp. a.

Spiriferina billingsi.

Spiriferina laxa.

Spiriferina hilli var. polypleurus.

Spiriferina welleri?

Composita emarginata?

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia meekana var. trigonalis.

Hustedia papillata.

Hustedia bipartita?

Pugnax bisulcata.

Pugnax bisulcata var. seminuloides.

Pugnax bisulcata var. gratiosa.

Pugnax swallowiana?

Pugnax osagensis?

Pugnax bidentata.

Pugnax pinguis.

Pugnax sp. a.

Rhynchonella? indentata.

Dielasma spatulatum.

Dielasmina guadalupensis.

Notothyris schuchertensis var. ovata?

Myalina squamosa?

Aviculipecten guadalupensis.

Aviculipecten sp. a.

Euomphalus sulcifer.

Euomphalus sulcifer var. angulatus.

Anisopyge perannulata.

Cythere? sp.

The position of this loose material was such that little if any could have come from high in the Capitan, and little if any from below the top of the Delaware Mountain formation. The rock is a limestone partly dark colored and partly a light brown. The fauna shows rather marked differences from that obtained midway in the Capitan formation, species occurring in one which are not found in the other, or being abundant in one and rare in the other. On the other hand, there is a considerable community of forms. Some of the more distinguishing characteristics of this "dark limestone" fauna are the abundance of Fusulina elongata, which, though occurring in the greatest profusion at the top of the Capitan (station 2905), seemed to be absent from the point where our typical Capitan fauna was obtained (station 2926), the greater abundance of cup corals, the presence of Cladopora spinulata, the greater abundance of the Domoporas and other Bryozoa, the presence of Chonetes permianus and C. subliratus, the abundance of small Producti of the semireticulatus group, such as P. popei, P. indentatus, etc., the presence of Aulosteges guadalupensis and Spiriferina laxa, the abundance of the group of Pugnax bisulcata,a the presence of Aviculipecten guadalupensis, and of Euomphalus sulcifer and its variety angulatus, and the abundance of Anisopyge perannulata. An equal number of distinctive forms might be named on the part of the Capitan fauna. The faunas of stations 2926 and 2930 are marked by about the same differences which originally distinguished Shumard's "dark limestone" from his "white limestone," but our more extensive collections show more differences than his rather meager ones. I believe, therefore, that our collection 2930 is Shumard's "dark limestone" fauna, and that it is represented stratigraphically by a not very thick series of dark-colored limestones occurring at the junction of the Delaware Mountain formation with the Capitan. The Capitan fauna, as exemplified by the collections obtained in its middle portion at station 2926, and the fauna of the "dark limestone" show well-marked differences, and suggest the question whether the latter should be grouped as a lower division of the Capitan, as a distinct member, or as a portion of the Delaware Mountain formation.

aOnly a single specimen of this species is contained in our collection from station 2926, and the lithology suggests that it may really have come from the "dark limestone."

For purposes of stratigraphy it would perhaps be more convenient to divide the two series in the vicinity of Guadalupe Point at the top of the sandstones, but lithologically the "dark limestone" shows greater resemblance to the dark-colored calcareous members of the Delaware Mountain formation in which Richardson has included it, than to the white limestone of the typical Capitan.

Faunally, if we consider only the collections made in the sandstones of the Delaware Mountain, the "dark limestone" is quite different from that division and would probably have to be regarded as a distinct series, or, better, as a subdivision of the Capitan. Evidence will appear in its turn, however, which indicates that the "dark limestone" is really a part of the Delaware Mountain formation.

Before turning to the discussion of the typical Delaware Mountain fauna it will be desirable to comment on some collections from the upper series made by R. T. Hill. They were obtained at the south end of the Guadalupe Mountains, at a horizon described merely as the "upper limestone." They may, consequently, have come from either the "dark limestone" or the Capitan. The species identified are as follows:

Station 3762.

Productus semireticulatus var. capitanensis.

Fusulina elongata.

Endothyra sp. a.

Station 3762a.

Fusulina elongata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Spiriferina welleri var. a.

Hustedia meekana.

Station 3762b.

Lindstroemia permiana?

Lindstroemia sp.

Zaphrentis? sp.

Amplexus sp.

Cladopora spinulata.

Archaeocidaris cratis?

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora? ocellata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Chonetes permianus.

Richthofenia permiana.

Hustedia meekana.

Station 3762c.

Archaeocidaris sp. a.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Station 3762d.

Lindstroemia permiana var.

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora? ocellata?

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Leioclema shumardi ?

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Hustedia meekana.

Dielasma spatulatum?

Station 3762e.

Lindstroemia permiana var.?

Cladopora spinulata.

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora? ocellata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Leioclema shumardi.

Fenestella hilli.

Polypora mexicana?

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia sp.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spiriferina laxa?

Hustedia bipartita?

In no instance do these lists indicate the fauna obtained from the middle portion of the Capitan limestone, and several appear to present the fauna of the "dark limestone." Lots 3762b, 3762d, and 3762e are the most clearly indicative of the "dark limestone" and 3762 and 3762c the most ambiguous. From the manner in which the Fusulinas are preserved in lot 3762, I am disposed to believe that it came from the highest beds of the Capitan. It has been provisionally assigned to this horizon in the records published here, and the other collections have been placed in the "dark limestone."

From the sandstones of the Delaware Mountain formation I obtained material at only three points, and since fossils are not so abundant or so well preserved in these sandstones as at other horizons my collections are a little meager. From about 250 feet above the base of the formation (station 2919) the following forms have been identified:

Fusulina elongata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Enteletes sp. d.

Chonetes subliratus.

Productus waagenianus var.

Productus texanus?

Productus sp. a.

Productus guadalupensis.

Spirifer sp. b.

Martinia rhomboidalis.

Squamularia guadalupensis.

Composita emarginata?

Hustedia papillata.

The two other collections were obtained at about the same level, approximately 700 feet up in the formation. One of these (station 2903) furnished the following species:

Fusulina elongata.

Fusulinella sp. a.

Chonetes sp.

Productus waagenianus var.

Productus texanus.

Productus sp. a.

Productus latidorsatus.

Productus walcottianus.

At the other (station 2931) I obtained the forms named in the following list:

Fusulina elongata.Chonetes sp.

Productus guadalupensis.

Productus meekanus.

Productus signatus.

Productus signatus var.

Productus sp. e.

Productus subhorridus var. rugatulus?

Productus walcottianus.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spiriferina billingsi?

Pugnax osagensis?

Leptodus americanus.

Edmondia? bellula?

Edmondia sp.

Nucula sp. b.

Parallelodon multistriatus.

Parallelodon politus.

Bakewellia? sp.

Pteria richardsoni?

Pteria sp.

Myalina permiana?

Camptonectes? papillatus.

Aviculipecten delawarensis.

Acanthopecten aff. A. carboniferus.

Pernipecten obliquus.

Myoconcha costulata var. delawarensis.

Astartella nasuta.

Pleurophorus delawarensis.

Cleidophorus pallasi var. delawarensis.

Plagioglypta canna?

Pleurotomaria multilineata.

Pleurotomaria sp. d.

Pleurotomaria euglyphea.

Pleurotomaria strigillata?

Pleurotomaria arenaria.

Pleurotomaria? planulata.

Pleurotomaria? delawarensis.

Pleurotomaria? carinifera.

Bucanopsis sp.

Warthia americana.

Naticopsis sp.

Pseudomelania sp. a.

Bulimorpha chrysalis var. delawarensis.

Macrocheilina? sp. a.

Orthoceras guadalupense.

Gastrioceras serratum.

Anisopyge perannulata.

To these may be added a collection made by Mr. Elder from one of the limestone members in the Delaware Mountain formation not far above the last two. Here (station 2963) he obtained five species, as follows:

Fusulina elongata.

Stromatidium typicale?

Cladopora spinulata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Stenopora polyspinosa var. richardsoni?

In the same region, but from a somewhat higher horizon (station 2968), Mr. Richardson collected the following species:

Lindstroemia permiana var.

Paraceltites elegans.

Gastrioceras sp.

As disclosed by these collections, the fauna of the Delaware Mountain formation presents many differences from either that of the "dark limestone" or that of the Capitan formation. The chief positive difference consists in the development of a relatively extensive suite of Pelecypoda and Gasteropoda, in the main very unlike those which succeeded them. Negatively, the Brachiopoda are less abundant and well differentiated. Consequently many of the forms characteristic of the series next above are wanting. The brachiopods which are present are in part the same, but the Productus fauna of this division seems to be distinct from that of either the "dark limestone" or the Capitan.

The black limestone at the base of the Guadalupe section is not as a rule highly fossiliferous, but would surely furnish an interesting and extensive series of forms if carefully collected. I had time to essay the black limestone at only one point. It was not found to be fossiliferous there except near the top (station 2920), where I obtained the following species:

Anthracosycon ficus.

Anthracosycon ? sp.

Enteletes sp. C.

Orthotetes? sp. a.

Chonetes sp.

Productus latidorsatus var.

Richthofenia permiana.

Composita mexicana var. guadalupensis.

Hustedia meekana.

Pugnax nitida.

Pugnax osagensis.

Pugnax bidentata.

Rhynchonella longaeva?

Leda sp.

Plagiostoma deltoideum?

Pleurotomaria strigillata.

Pleurotomaria arenaria var. monilifera.

Euomphalus sulcifer.

Foordoceras shumardianum var. praecursor.

Peritrochia erebus.

Bairdia aff. B. plebeia.

A collection from about the same locality and horizon (station 2967) brought in by Mr. Elder presents to a considerable extent a different facies, as follows:

Stenopora granulosa?

Enteletes sp. c.

Meekella attenuata.

Meekella multilirata.

Aulosteges sp. a.

Aulosteges sp. b.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spirifer sp. b.

Composita mexicana var. guadalupensis.

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia papillata?

Pugnax? pusilla.

Solenomya? sp.

Clinopistha? cf. C. radiata var. laevis.

Nucula sp. a.

Nucula sp. b?

Yoldia sp.

Aviculipecten sp. a?

Pleurotomaria strigillata.

Naticopsis sp.

Loxonema? inconspicuum.

Macrocheilina? modesta.

Foordoceras shumardianum var. praecursor.

Agathoceras texanum.

Paraceltites elegans.

Anisopyge perannulata.

Anisopyge? antiqua.

This fauna is unusually well balanced, containing Brachiopoda, Pelecypoda, Gasteropoda, and Cephalopoda in nearly equal proportions, besides a corresponding share of other groups. At this horizon, in fact, the ammonoids appear from our collections to be more abundant than at any other in the typical Guadalupian section. It is interesting to note that they have a Permian aspect, an indication which is corroborated by the presence of Richthofenia and Aulosteges. While unmistakably related to the overlying faunas, that of the basal black limestone has an individual facies. It is widely different from any of the known faunas of the Hueco formation, and without doubt is to be regarded as a member of the Guadalupian series. It may be remarked that neither as a lithologic nor as a faunal unit is this limestone known to occur except in the immediate region of Guadalupe Point.

In the section exposed at the south end of the Guadalupe Mountains there are, according to our collections, four rather well-marked faunas, which occur in the basal black limestone, the Delaware Mountain formation, the "dark limestone," and the Capitan formation.

As already remarked, in the Delaware Mountain formation, which even in the vicinity of Guadalupe Peak is more or less interspersed with dark limestone, the calcareous component appears to become more and more important as the strata are followed southward into the southern Delawares, where almost the whole of the section is composed of limestone beds. This area was not visited by me, but collections were made by Mr. Richardson and Mr. Elder from a number of different localities and horizons. From a point 7 miles north of Marley's ranch (station 2935) Mr. Richardson obtained the following collection:

Martinia rhomboidalis.Pernipecten obliquus.

Pleurotomaria putilla?

Euconospira sp.

Bellerophon crassus.

From the low hills west of Marley's (station 2936) the two following species were collected: Chonetes permianus and Ambocoelia planiconvexa var. guadalupensis. A collection made 1-1/2 miles east of Marley's ranch (station 3501) contains four forms, as follows:

Enteletes sp. d.

Derbya sp. a.

Meekella skenoides.

Spirifer sp. b.

At another point, about 15 miles north of Marley's (station 3500), the following species were collected:

Fusulina elongata.Lindstroemia permiana.

Archaeocidaris sp. d.

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora? ocellata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Stenopora polyspinosa var. richardsoni?

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Derbya? crenulata.

Composita emarginata var. affinis?

Hustedia meekana.

Pugnax bisulcata var. seminuloides.

Gastrioceras serratum?

At about the same locality as the foregoing was obtained the largest of all the faunas collected in the southern Delawares (station 2969). The following species have been identified:

Fusulina elongata.Fusulinella sp. b.

Fusulinella sp. C.

Stromatidium typicale.

Lindstroemia permiana?

Lindstroemia permiana var.

Cladopora spinulata.

Cladopora tubulata.

Aulopora sp.

Coenocystis richardsoni.

Archaeocidaris sp. b.

Archaeocidaris sp. b var.

Archaeocidaris sp. d.

Spirorbis texanus.

Domopora? terminalis.

Domopora? ocellata.

Domopora? vittata.

Domopora? incrustans.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Stenopora polyspinosa var. richardsoni.

Leioclema shumardi?

?Fenestella spinulosa?

Fenestella texana.

Fenestella sp. a.

Fenestella sp. b.

Fenestella sp. c.

Fenestella sp. e.

Fenestella sp. f.

Fenestella sp. f?

Polypora sp. a.

Polypora sp. b.

Polypora sp. c.

Polypora sp. d.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Rhombopora? sp.

Goniocladia americana.

Derbya? crenulata.

Derbya sp. b.

Orthotetes guadalupensis?

Chonetes permianus.

Productus walcottianus?

Productus? pileolus.

Productus sp. d.

Strophalosia sp.

Spirifer mexicanus var.

Spiriferina billingsi?

Spiriferina sulcata?

Spiriferina laxa.

Spiriferina pyramidalis?

Spiriferina hilli var. polypleurus.

Spiriferina welleri?

Spiriferina welleri var. b.

Composita emarginata var. affinis?

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia bipartita.

Pugnax bisulcata var. seminuloides.

Dielasma prolongatum.

Notothyris schuchertensis var. ovata.

Heterelasma shumardianum.

Heterelasma venustulum.

Leptodus americanus.

Nucula sp. C.

Parallelodon politus?

Pteria richardsoni.

Myalina squamosa?

Protrete texana.

Cymatochiton? texanus.

Pleurotomaria texana.

Pleurotomaria cf. P. planulata.

Pleurotomaria elderi.

Murchisonia? sp. a.

Murchisonia? sp. b.

Warthia americana?

Turbo? sp.

Pseudomelania? sp. b.

Anisopyge perannulata.

Argilloecia sp.

At station 2957, which is situated 45 miles south of El Capitan, the following species were collected:

Fusulina elongata.Fusulinella sp. a.

Zaphrentis? sp. ?

Domopora? ocellata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Rhombopora? sp.

Productus popei.

Strophalosia sp.

About 20 miles north of the railroad station called Plateau (station 2962) Mr. Elliott collected the following:

Cladopora spinulata.Domopora? ocellata.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Actinotrypa? sera.

Streptorhynchus pygmaeum?

Streptorhynchus perattenuatum.

Derbya sp. a.

Orthotetes guadalupensis?

Martinia rhomboidalis.

Squamularia guadalupensis.

Dielasma spatulatum?

In a collection made 10 miles northwest of Kent (station 2964) the following species were identified:

Fusulina elongata.Endothyra sp. C.

Lingulina? sp.

Guadalupia? sp. var.

Cystothalamia nodulifera.

Lindstroemia permiana?

Richthofenia permiana.

Pugnax osagensis.

Pleurophorus sp.

Pleurotomaria richardsoni?

Pleurotomaria? carinifera var.

Bellerophon crassus.

Macrocheilina? sp. b.

Finally, a small collection made 35 miles northeast of Van Horn (station 2965) furnished Pugnax? bisulcata var. seminuloides and Waagenoceras cumminsi var. guadalupense.

These collections from the limestones of the southern Delawares have a fauna which is somewhat ambiguous. In the main it seems to be that of the "dark limestone" of the Guadalupe Mountains. This is suggested by the Bryozoa and corals and by the abundance of Pugnax bisulcata var. seminuloides, Chonetes permianus, etc. In no instance is there a recurrence of the characteristic fauna found near the middle of the Capitan formation, yet in a good many of these collections Capitan species have been identified which in the Guadalupe section have not been found in the "dark limestone." I refer to Goniocladia americana, Productus? pileolus, Heterelasma shumardianum, H. venustulum, and a few others. The sandstones of Guadalupe section have to a considerable extent different species. Nevertheless, in view of the facts that we still know the Guadalupian faunas very incompletely, that lithologically these limestones of the southern Delawares resemble those of the typical Delaware Mountain sections, that from observations in the field they appear to replace and represent the sandstones of that formation, that the conditions of limestone deposition on the one hand and of sandstone deposition on the other would probably influence the character of the faunas, and that our collections from the sandstones of the Delaware Mountain were made chiefly in the lower half of the formation, while in the southern Delawares they were probably made in the upper portion—in view of these facts I am ready to believe that these southern faunas do not represent any horizon of the typical Guadalupe section above the "dark limestone." It is unfortunate that we know so little of the forms which occur in the limestones of the Delaware Mountain formation in the Guadalupe sections. I neglected them entirely, and the two collections brought in by Richardson's party are too meager to be of much service. The faunas from the southern Delawares seem to show that at least some of the Capitan species range lower than is indicated by our data from Guadalupe Point. These faunas are so closely allied to that of the "dark limestone" as to suggest that the latter belongs with them rather than with the Capitan formation. This may not mean the elimination of the "dark limestone" as a distinguishable faunal facies, for it may characterize the upper portion of the Delaware Mountain formation while the lower portion also has a facies of its own.

Although the Guadalupian series is supposed not to occur in the Diablo Mountains, this memoir involves a small suite of fossils which are reported to have come from that range. They were found among the collections of the National Museum, having been received from E. T. Dumble in 1892. On internal evidence I have divided this material into two parts. One of these appears to consist of collections made by Von Streeruwitz and mentioned in his report,a although the different lots are now intermingled so that nothing can be exactly located. This fauna is that of the Hueco formation, which Richardson found to be the dominating if not the only Carboniferous formation in the Diablo Mountains.

aAnn. Rept. Geol. Survey Texas for 1892, 1893, p. 170.

The remaining portion of the material differs lithologically from the other. In the main the fauna also is widely different, not only from that of the other assemblage of forms, but from anything since obtained in the Diablo Mountains, or from the Hueco fauna as a whole. It contains some striking types, such as Leptodus, which are supposed to be characteristic of the Guadalupian, and yet it is not identical with any of the known Guadalupian faunas. While of too interesting a nature to be omitted from the present report, a twofold uncertainty, therefore, surrounds this material, since a question may be raised not only as to whether it belongs to the Guadalupian fauna, but as to whether it was obtained front the Diablo Mountains. As some of the striking forms were not mentioned by Walcott, who I believe determined the fossils for Von Streeruwitz's report, it is possible to suppose that the collection was not made in the Diablo Mountains, but was sent in at the same time, possibly from the same general region, and thrown in with the Diablo forms. As to the other point, the Guadalupian fauna seems to be so extensive, and as yet so imperfectly known, that it is, theoretically at least, quite possible for local collections from a distinct area to present an individual facies and yet to belong to the same period.

The following species are present in the fauna determined in this way (station 3764), and it will be seen that the facies is considerably different from any of the faunas of the Guadalupe section or of the southern Delawares:

Lindstroemia permiana.

Cladopora tubulata.

Thamniscus digitatus.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Enteletes dumblei.

Enteletes angulatus.

Enteletes sp. c.

Derbya nasuta.

Derbya? crenulata.

Meekella attenuata.

Leptodus americanus.

Two more collections are included in this report which show considerable individuality of facies and yet without much doubt belong to the Guadalupian series. They were made by R. T. Hill in the vicinity of Marathon, Tex., nearly 150 miles southeast of the Guadalupes. One of them was obtained in the Glass Mountains, 17 miles northwest of Marathon (station 3763). From this point I have identified the following species:

Fusulina elongata.

Guadalupia zitteliana.

Cystothalamia nodulifera.

Lindstroemia permiana.

Zaphrentis? sp.

Amplexus sp.

Cladopora spinulata.

Domopora? ocellata.

Domopora? hillana.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Fistulipora sp.

Meekopora sp.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Enteletes globulosus.

Enteletes sp. a.

Enteletes sp. b.

Enteletes sp. d?.

Streptorhynchus pygmaeum.

Streptorhynchus? sp. a.

Orthotetes guadalupensis?

Orthotetes distortus.

Orthotetes? sp. a.

Meekella skenoides.

Meekella difficilis.

Productus sp. c.

Productus guadalupensis var. comancheanus.

Productus meekanus.

Productus subhorridus var. rugatulus.

Strophalosia hystricula.

Richthofenia permiana.

Spirifer sp. b.

Squamularia guadalupensis.

Spiriferina billingsi?

Spiriferina hilli.

Composita emarginata var. affinis?

Composita mexicana.

Hustedia meekana.

Hustedia papillata.

Hustedia bipartita.

Camarophoria venusta.

Notothyris sp.

Leptodus americanus.

Parallelodon multistriatus.

Parallelodon? sp.

Pteria squamifera.

Aviculipecten sp. b.

Aviculipecten sp. b var.

Aviculipecten sp. c.

Aviculipecten sublaqueatus.

Astartella nasuta.

Pleurotomaria richardsoni?

The other locality (station 3840), which is described merely as the "mountains northwest of Marathon," has furnished the following species:

Fusilina elongata.

Platycrinus? sp.

Phyllopora ? sp.

Thamniscus sp.

Septopora aff. S. robusta.

Rhombopora aff. R. lepidodendroides.

Rhombopora? sp.

Acanthocladia guadalupensis.

Fistulipora grandis var. guadalupensis.

Meekella difficilis.

Productus subhorridus var. rugatulus.

Aulosteges magnicostatus.

Spiriferina welleri?

These two faunas are evidently related to one another and in a general way to those of the Guadalupe and Delaware mountains. Their resemblance to any of the facies manifested in those areas is far from being so close that they may be called identical, but is greater to the fauna of the Delaware Mountain sandstone than to that of the Capitan limestone, or even to that of the "dark limestone." Accordingly, I have provisionally registered these forms as from the Delaware Mountain formation.

Thus different degrees of uncertainty are involved in the faunal relation of these collections to the Guadalupe section, and in some cases in their geographic position as well, and it seems best to refer to this matter here and to omit for the most part from the account of range and distribution that follows each species the marks of query really needed to express the modified certainty with which some of the assignments are made. As a rule where an interrogation point is used it refers to the identification of the species.

In view of the different localities and different horizons represented by the subject-matter of this report the determination of the best method of arranging the illustrations of species has been a matter of some concern. Since the ultimate purpose here, as in my other work, is faunal, the use of a zoological arrangement which would obscure the original assemblages of formational or regional groups of species seemed objectionable. On the other hand, when trying to compare several species, or to consult the illustrations of only one, I have found it highly annoying to be compelled to refer to several plates. Still, the grouping to the eye of forms associated in nature seems to me too important to be lightly dispensed with, and the loss of this instructive arrangement the greater of the two evils. An attempt to ameliorate the trouble occasioned by having kindred forms distributed on several plates has been made in connection with the arrangement of the figures on the plates themselves, so that they have rather rigidly been placed in serial order. This militates against a balanced appearance of the plate, which is very agreeable; but in some works, a class of which those of Gemmellaro may be cited as instances, the illustrations are so artistically distributed that it is almost impossible to find them. After losing much time over Gemmellaro's plates and others like them, it has seemed to me that this is a matter in which utility outweighs beauty as a desideratum. Consequently the plates in this report will be found arranged according to the stratigraphic and geographic groups in which the different collections have been considered above. Although this method does not misrepresent the natural grouping, it fails to represent it completely, because I have not sought to figure the common or recurrent forms in each set of plates.

Although in one particular the present report adds considerable to the available knowledge of the Guadalupian fauna, in another its contribution is small, for geographically the fauna is restricted, so far as known, to the general region where it was first discovered. It is quite unlike the faunas of eastern North America and almost equally unlike most of those of the West which I have seen. Of the latter a very few suggest the Guadalupian in some degree, but for one reason or another, because our material is very scanty or the resemblance remote, it has seemed best to reserve these instances for future discussion. This limited distribution of the Guadalupian need not indicate an extremely local development of a fauna contemporaneous, perhaps, with others of a different facies which we already know, but it may be due to several causes—to our incomplete knowledge, especially of western faunas; to the fact that the Guadalupian beds may be represented elsewhere by strata which do not contain invertebrate fossils, such as red beds; or to the removal by erosion of a part of the Guadalupian deposits, which were formerly more extensive. Probably all three causes contribute to limiting the present knowledge of the Guadalupian territorially.

The difference manifested by the faunas of the Guadalupe Mountains from those of the rest of North America, though not necessarily, at least in fact involves a resemblance to certain Asiatic and European faunas. Rather careful comparisons have been made with these alien faunas, but although evidently related to some of them the Guadalupian seems, as indicated farther on, to maintain a highly individual facies.

Aside from the species which Shumard had described, most of the Guadalupian forms appeared to be new. So different are the Guadalupian and Pennsylvanian faunas that in most cases the species of the one have no related species in the other, but the Pennsylvanian literature has been searched with care for kindred forms, and where found the usual comparisons have been instituted. It has been found necessary, however, to import few names of Pennsylvanian species into the Guadalupian fauna. Still fewer have been introduced from foreign literature, though I have been careful to note instances where it seemed that a relationship existed. But in the latter case particularly, even when the relationship seemed rather close, the Guadalupian form has generally been given a new name, because the data were not at hand by which I could reach a conclusion as to their identity or distinction.

It is reasonably safe to depend on descriptions and figures for an identification of species where the geographic separation is not wide and where the faunal association is essentially the same, but, otherwise, characteristic specimens are necessary for a satisfactory comparison. In the present case all these conditions were conspicuously absent. The most nearly related foreign faunas were separated by a terrestrial quadrant. They prove to have in the main a very different facies, to be related in one species and different in twenty, and I was practically without foreign material with which to make comparisons when comparisons were most desirable.

It has been said not less truly than often that it is easier to combine two species that have been injudiciously discriminated than to disengage two species that have been injudiciously combined, and it is also true that loose discriminations and loose identifications lead to loose correlations. I have felt under obligation to other workers in this field to leave a species whose relationship I was unable to determine as unentangled as possible, and to establish the nomenclature on a reasonably independent and permanent basis. Consequently, in doubtful cases I have leaned consciously to the side of species making, nor would I feel deeply concerned should it prove on just evidence not now accessible to me that some of my names are synonyms.