|

California Division of Mines and Geology

Bulletin 202 Geology of the Point Reyes Peninsula, Marin County, California |

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY

Coal and Peat

In the last half of the 19th century, before abundant oil was discovered, strenuous efforts were being made in California to locate supplies of coal as a substitute for wood for fuel. Two explorations for coal on Point Reyes Peninsula were reported. The first one was on the Nelson Olds (now Boyd Stewart) Ranch near Olema, where a prospecting tunnel 325 feet long was dug in 1875 (Marin Journal, November 8, 1875). The location is in the lakebeds of the Olema Creek Formation (Pleistocene?), which are very peaty. Evidently not enough peat was found to justify further work. These peaty beds can be seen in the roadcut on the east side of State Highway 1, just south of the entrance to the Boyd Stewart Ranch.

Parker (1893) mentions specimens of "coal" from the banks of Pine Gulch Creek near Bolinas. Watts (1893) mentions that "some prospecting for coal has been done about 2 miles north of Bolinas, on the McGovern Ranch. No coal, however, is in sight, the formation exposed being a dark colored shale." This prospect hole, excavated in dark grey-black Monterey Shale on the bank of Pine Creek Gulch, is still referred to as "the coal mine" by nearby ranchers.

Gold

The Petaluma Journal and Argus of February 15, 1868, has the following lively description of a gold discovery on Tomales Point:

"There was quite an excitement created by the discovery of gold on the beach at Pierce's Point, which forms the southern share at the entrance of Tomales Bay. Some men from Preston's Point crossed over to the place above named to gather mussels, and one of them while drinking from a brook that came down from the bluff, discovered some scale gold. Procuring a pan they got good prospects, which induced them to construct a sluice, through which they washed the earth from the bottom of the ravine, realizing $15.00 to the hand for a day's work. Where they worked is only accessible at low tide. We would not counsel a rush of over ten thousand miners to the new diggings."

Munro-Fraser (1880, p. 311) says,

"At Tomales Point there is a place called Gold gulch, where sluices were put in and placer mining carried on quite extensively in 1865-66, and the yield averaged two dollars and a half a day to the man. It is fine flake dust, hence much of it was lost. Lack of water caused them to abandon the enterprise. There are also quartz lodes here that promise well. Seven assays averaged of gold thirty dollars and eighty-three cents and of silver fifty four dollars and ten cents."

Trask (1856, p. 13) writes that "at Point Tomales on the west shore of the bay, gold also abounds but in small quantity. It is found about one mile from the northern end of the point, near the settlements on that shore." Irelan (1888, p. 342) reports "on the ocean side of Tomales Point occurs a deposit of auriferous black sand. It can only be reached at low tide." Ver Planck (1955) mentions a prospect shaft, probably sunk for gold, near Willow Point on Tomales Bay. These occurrences apparently were not sufficiently large to encourage further exploration and nothing more is known of them today. However, panning the streams and beaches near these localities might yield interesting results. (Landowners' permission would, of course, be required.)

Greensand

Greensands, or sands containing glauconite, a green mineral which is essentially a hydrous potassium iron silicate, have occasionally been used commercially as water softeners and as a source of potash for fertilizer. Considerable concentrations of glauconite occur in the greensand at the base of the Drakes Bay Formation; however to the writer's knowledge the material has never been exploited here and it is not known whether the occurrence is commercial.

Limestone

Limestone for the manufacture of cement was naturally in great demand in the early days of San Francisco; and before supplies became available from the large quarries south of the city, efforts were made to develop some of the local deposits in the Point Reyes Peninsula. Small kilns and quarries are found 3/4 mile west of Inverness Park; these are referred to by Blake (1856), who writes "thick beds of good white limestone" are found near Tomales Bay "which are quarried and calcined for the San Francisco market." This Inverness Park exposure is referred to in the literature also as "the Lockhart tract" or the "Trout Farm" quarry. Anderson (1899) refers to it as being "on the 'old road' which crosses the summit from the head of Tomales Bay."

The accompanying geologic map shows that the Inverness Park (Lockhart) limestone is associated with nearby limestone exposures to the south in Haggerty Gulch and on the Noren property. The intervening area is covered with vegetation, so it is possible that the limestone of Inverness Park is more extensive to the southeast than shown. The main outcrop on the old Laguna Ranch road is covered on the southwest side by Miocene sediments, so it could extend in this direction also, as suggested by Eckel (1933). However, there is considerable faulting in this area, as is indicated by the anomalous shape of the nearby contacts, and core drilling would be necessary to explore under the Miocene cover before any assumptions as to its extension westward could be safely made.

Two core holes have been drilled in the area by a cement company. One encountered only granitic rock which was deeply weathered to about 60 feet, and the other encountered limestone which was probably interbedded with schist and impregnated with granitic material. It was concluded that the deposit was not of sufficient size nor thickness to be of economic value. Examination of the Haggerty Gulch outcrops bears out this conclusion since the limestone there occurs in thin beds interbedded with schist and permeated with stringers of igneous rock.

This, too, is characteristic of the other metamorphic limestone occurrences shown on the map; namely, those on Mt. Wittenburg, and on the Bender place at Willow Point. As additional subdivision roads are cut in the Inverness area, more limestone occurrences may be exposed, but the possibility does not seem to be good that any of them will be of economic value because: (1) known occurrences are all thin-bedded and intermixed with schist and granitic material and (2) the surface mapping has been sufficiently detailed to have detected any extensive body of thick limestone, except in the densely vegetated areas.

In addition to the limestones of the metamorphic group, two occurrences of Calera (Franciscan) limestone in the San Andreas fault zone have been observed. One of these is at the well known so-called Russian lime kilns near Five Brooks, described in interesting detail by Treganza (1951) and already described in this report. The outcrop at the Russian lime kilns is quite small, and it appears to be a tectonic inclusion in the fault zone. There is little reason to think it extends laterally much beyond the outcrop area, although some fragments of limestone are to be found in the fault zone about 1000 feet to the southeast.

The other occurrence is located about 2 miles southeast of the Russian lime kilns and is marked by the presence of old kilns. Presumably the outcrop is similarly limited in size, although the outcrop is too badly obscured to be able to determine its size. Limestone analyses made by previous workers are listed in table 11. While there are numerous limestone outcrops in the area, and more will probably be found, it seems unlikely that an economic deposit exists, because of the interbedding of the pure limestone layers with beds of schist and permeation of the whole with intrusive igneous rock.

Table 11. Analyses of limestones. Adapted from Eckel, 1933, p. 358.

| Location no. |

SiO2 (%) |

Al2O3 (%) |

Fe2O3 (%) |

CaCO3 (%) |

CaO (%) |

MgCO3 (%) |

MgO (%) |

CO2 (%) |

| 1 | 1.66 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 96.60 | n.d. | 0.75n.d. | n.d. | |

| 2 | 2.26 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 95.48 | n.d. | 1.10 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 3 | 2.3 | 0.76 | incl. | 96.0 | 53.8 | n.d. | 0.35 | 42.7 |

| 4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | incl. | 97.0 | 54.32 | n.d. | 1.25 | 42.68 |

| 5 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.35 | 97.50 | n.d. | 1.60 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 6 | 1.1 | 0.68 | incl. | 97.8 | 54.8 | n.d. | tr. | 43.2 |

| 7 | 1.90 | 0.76 | 0.20 | 96.74 | n.d. | 0.33 | n.d. | n.d. |

Location no.: 1Old quarry near Trout Farm. Marin County. Sampled and analyzed by C.A. Newhall. 2Lockhart tract near Inverness Park. Marin County. Sampled and analyzed by C.A. Newhall. 3Lockhart tract near Inverness Park. Marin County. Sampled by E.C. Eckel, analyzed by U.S. Bureau of Standards. 4Near Inverness Park. Marin County. Sampled and analyzed by F. Huber. 5West of head of Tomales Bay. Analysis given by Anderson (1899). 6Russian lime kiln. south of Olema, Marin County. Sampled by Junes Kelly. analyzed by U.S. Bureau of Standards. 7Russian lime kiln, south of Olema, Marin County. Sampled and analyzed by C.A. Newhall. | ||||||||

Petroleum

Abundant signs of petroleum are present on the Point Reyes Peninsula, but no commercial production has been established. Along the beaches and cliffs between Duxbury Point and Double Point, oil-filled joints are conspicuous in the Monterey Shale, and thick tar and oil-sands occur at the Miocene-Pliocene contact from south of Double Point northward to Bear Valley. The sandstone dikes which are common in this vicinity are often bituminous. A spectacular gas seep in the Duxbury Point area was reported by Holder (1893), the Marin Journal (January 5, 1893), Crawford (1896), St. Amant (1905), Bingham (1906), Douglas and Rhoades (1915), and Bradley (1915). This seep, which apparently was big enough to cook fish on when lighted, is not evident today. Judging by the descriptions, it probably emerged from a joint-plane fissure in the Monterey Shale. Erosion of the cliff has doubtless resulted in the seep now being covered by the sea and beach. Further north, near Double Point, the writer has observed an active oil and gas seep visible at low tide.

Attracted by the oil and gas seepages along the coast near Duxbury Point and Arroyo Hondo, and encouraged by the discovery of oil in Humboldt County, the Arroyo Hondo Petroleum Company, backed by George T. Hearst and others, drilled a shallow wildcat well at the mouth of the Arroyo Hondo in 1865. At the same time another well was drilled by the Bolinas Petroleum Company, on the point at the entrance of Bolinas Bay. Enthusiasm ran high, and the Petroleum Hotel was established at Bolinas, but no oil in commercial quantity was found. The wells were very shallow, not over 400 feet in depth, and no information is available on their findings. Apparently the Arroyo Hondo well was drilled entirely in Monterey Shale, and the Bolinas well in Merced Formation.

From 1900 to 1906, there was more oil exploration with two or three wells drilled in the vicinity of Duxbury Point, on the Garzoli Ranch. The casing of one well can still be seen sticking out of the cliff at the intersection of Rosewood Road and Ocean Parkway on Bolinas Mesa. These unsuccessful wells were about 2000 feet in depth and one was drilled to 2800 feet and reportedly produced a few barrels of heavy oil per day from the Monterey Shale. The report of this small production does not seem improbable in view of the oil filled joints and the historic gas seep at this location. Another shallow dry hole was drilled at this time near Arroyo Hondo.

In the 1950's another group of wells was drilled. Several of these were relatively deep and were located with the aid of careful geological work, but again none was successful. Table 12 presents data on these exploratory wells.

Table 12. Records of exploratory wells to April 1, 1970.

| M. D B & M.1 | Name of company and well | Date started |

Date abandoned |

Total depth (feet) |

Geology | ||

| T | R | Sec | |||||

| 3 N | 9 W | 36 | P.M. Oil Company, No. 1 | 1954 | 1671 | 0-917 ft. Alluvium. 917-1671 ft. Franciscan. | |

| 2 N | 10 W | 4 | Standard Oil Co., Molseed No. 1 | 1951 | 1951 | 1780 | 0-1620 ft. Drakes Bay Formation, Pliocene. 1620-1780 ft. "Granite". (Corehole) |

| 2 N | 10 W | 17 | Standard Oil Co., Mendoza No. 1 | 5-51 | 1951 | 951 | 0-854 ft. Drakes Bay Formation, Pliocene. 854-951 ft. "Granite". |

| 2 N | 10 W | 17 | Standard Oil Co., Mendoza No. 2 | 1951 | 1951 | 1276 | 0-1248 ft. Drakes Bay Formation, Pliocene. 1248-1276 ft. "Granite". (Corehole) |

| 2 N | 8 W | 33 | Standard Oil Co., Robson No. 1 | 5-52 | 1952 | 7286 | 0-7286 ft. Entire section in Monterey Shale. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 7 | Standard Oil Co., (L.M. Lockhart,) Tevis No. 1 | 9-47 | 1951 | 6587 | Drilled to 5123 ft. by L.M. Lockhart

and abandoned Jan. 1948. Standard

Oil Co. took over the well April

1951 and deepened it to 6587 feet. 0-4685 ft. Monterey Shale including Mohnian, Luisian and Relizian. 4685-4795 ft. Laird sand. 4795-4910 ft. shale. 4910-5015 ft. volcanics. 5015-6587 ft. Lower Eocene, "C" zone or Paleocene. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 21 | Arroyo Honda Pet. Co. | 4-1865 | 1866 | 375 | Unknown. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 17 | W.A. Sherman, South End Ranch | 1903? | 1905? | ? | Unknown. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 35 | Leroy G. Harvey, Garzoli No. 12 | 1901 | 1905? | 1800 | Dry hole in Monterey. Showings at 700 ft. and 1200 ft. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 35 | Leroy G. Harvey, Garzoli No. 2 | 1905? | 2200 | Dry hole in Monterey. No showings. | |

| 1 N | 8 W | 35 | Leroy G. Harvey, Garzoli No. 32 | 1905? | 2700-2800 | Abandoned in Monterey. Reported a few barrels per day of low gravity oil. Casing still shows in cliff. | |

| 1 N | 8 W | 26 | Lockhart, L.M., R.C.A. 3-1 | 9-48 | 1949 | 8409 | Base "Santa Margarita" 2840 ft. Upper Mohnian 2840-4880 ft. Lower Mohnian 4880-8310 ft. Luisian 8310-8409 ft. Laird sandstone not reached. |

| 1 N | 8 W | 25 | Bolinas Pet. Co. Nott No. 1 | 1865 | 1865? | 80 | Unknown. |

| 1 N | 8 W | ? | Houston Jones | 1891 | ? | ? | Unknown. |

1Projected township, range, and section is from "Regional Wildcat Map" W6-1 of the California Division of Oil and Gas, January 15, 1966. 2The casing of an abandoned oil well, presumably one of the Garzoli wells since it is on the old Garzoli ranch, is to be seen about 100 feet northeast of the Clubhouse on Bolinas Mesa. The casing of another abandoned well, believed to be Garzoli No. 3, can be seen in the cliff face at the intersection of Bosewood and Ocean, on Bolinas Mesa. | |||||||

Although indications of petroleum are abundant, the presence of a good reservoir bed is questionable. The thick oil sands near Double Point are probably of local occurrence.

The Monterey Formation is mostly shale and no favorable beds are present except for the basal Laird Sandstone. This sandstone seems to be both porous and permeable in the outcrop, where it overlies the granitic basement; but in the Standard (Lockhart) Tevis #1 well at North Double Point, the probable correlative sand at a depth of 4690 to 4790 feet consisted of gray water-saturated sand in the lower part and seemed to be hard and impervious in the upper part. This sand is probably present as a possible objective in the area; but whether it is present everywhere in this area and whether it is sufficiently permeable is not known in the absence of further drilling.

Most of the anticlines noted in the section on local folds seem to be too small for an accumulation of oil which would justify the risk of drilling, even if other conditions were favorable.

Fault traps usually combine vertical faulting with a structural feature such as an anticline. Numerous faults are mapped or suspected in the area, but many of these are probably lateral in direction of displacement rather than vertical. Uncertainties in the mapping of anticlines apply equally to the mapping of any subsurface structural features associated with anticlines.

Stratigraphic traps are formed when oil or gas accumulates in the up-dip edge of a discontinuous sand or locally porous bed. The 100-foot sand which occurs in the Standard (Lockhart) Tevis #1 well at 4690 to 4790 feet probably diminishes in thickness northward approaching the basement and must terminate eastward against the San Andreas fault zone. Westward its position is unknown, but possibly it is present under the siltstones of the Drakes Bay Formation in the Point Reyes syncline.

In any of these situations, the geometry of the sand at some point might be such that oil or gas could accumulate; but it would be necessary to drill a series of exploratory tests to find such a trap, and the expense involved would appear to be far greater than the chances of success justify.

The structural complexity of the area, caused by the proximity of the San Andreas fault, and the small size of the structures that can be mapped, make the possibilities for commercial oil or gas accumulations unlikely, in spite of the numerous local oil and gas showings and the possible presence of a reservoir sand at depth.

Scheelite

Scheelite, a tungsten mineral (calcium tungstate, CaWO4) associated with limestone roof-pendants in the granitic rock, has been found at the Noren and Bender localities on the west side of Inverness Ridge. Neither has any commercial importance under present [1974] economic conditions.

Stone

A granite quarry was opened in 1854 at the east end of Point Reyes, at the point where the fishing-boat piers are now [1974] situated. This development was not successful, probably because the rock was so broken by faulting that no large blocks could be recovered.

Weathered granitic rock has been quarried for road material near the top of Inverness Ridge on the Drake's Summit road. This rock is badly decomposed and can be handled almost like gravel. Similar gravel pits are to be found in the vicinity of Inverness.

Small pits or quarries have been opened by ranchers in the Monterey Shale for the extraction of road material. The shale makes a very dusty road in summer, but it packs and drains well in the wet weather.

Water Supply

A detailed coverage of the water supply of the Point Reyes National Seashore is given by Dale and Rantz (1966).

As previously mentioned, precipitation on the peninsula is highly seasonal and more than 75 percent of the annual amount falls in the five months November through March. Consequently, 90 percent of the annual runoff occurs in the five months December through April, and many of the minor streams are intermittent in character, drying up in the late summer. For a reliable water supply, therefore, either perennial streams or porous and permeable aquifers must be utilized.

There are numerous perennial streams on the west side of Inverness Ridge, including Arroyo Hondo from which Bolinas obtains a water supply, Alamea Creek which meets the ocean just north of Double Point, Bear Valley Creek, and Glenbrook Creek. These streams have a relatively large drainage area on the southwest slopes of Inverness Ridge.

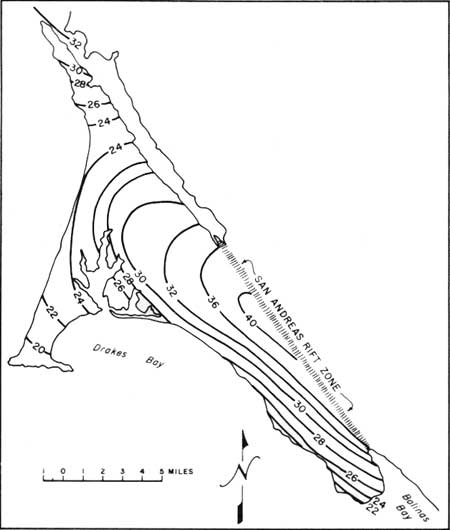

On the east side of Inverness Ridge, Olema Creek and Pine Gulch Creek flow northwest and southeast, respectively, along the San Andreas fault zone. These two streams are perennial. The precipitation map (figure 6) shows that rainfall on Inverness Ridge is the main source of water for these streams.

|

| Figure 6. Precipitation map, Point Reyes Peninsula. Contours are isohyets of average annual rainfall, in inches. Adapted from Dale and Rantz, 1966. |

In the synclinal area occupied by the Drakes Bay Formation and at Point Reyes, there are no streams of importance. Water discharges in small amounts from the dune sands and older beach deposits along Point Reyes Beach, and at McClures Beach a perennial creek draws its supply from these sources. Table 13 presents the flow of some of some streams on Point Reyes Peninsula.

Table 13. Low flow characteristics of streams on Point Reyes Peninsula (after Dale and Rantz, 1966).

| Name of stream and measurement point |

Discharge exceeded 60% of the time (gpm) |

Discharge exceeded 90% of the time (gpm) |

Firm yield.1 (gpm) |

| Pine Gulch Creek (near Woodville) | 410 | 190 | 60 |

| Alamea Creek (near Crystal Lake) | 420 | 270 | 180 |

| Bear Valley Creek (1 mile south of National Seashore Hq.) | 153 | 75 | 30 |

| Glenbrook Creek (close to Monterey—Drakes Bay contact) | 103 | 18 | 0 |

| McClure Creek (close to beach) | 66 | 40 | 25 |

1Firm yield is a discharge of such magnitude that only on one

Labor Day in 25 years, on the average, will it fail to be obtained.

| |||

The quality of the water on the peninsula is reported to be good for domestic use. Few of the geologic formations present in the Point Reyes Peninsula form good aquifers. The granitic basement is generally a poor aquifer, with wells yielding generally less than 1 gallon per minute. No water wells are reported in Paleocene sediments, and the Paleocene conglomerate exposed at Point Reyes appears to have little porosity or permeability.

The Laird Sandstone, if saturated, might be expected to yield about 10 gallons per minute to wells. The Monterey Shale and Drakes Bay Formation are unsatisfactory for water supply. In the vicinity of Bolinas domestic water wells in the Merced Formation yield 5 to 25 gallons per minute.

The most productive aquifers are coarse sands and gravels of Quaternary age. Wells in the sands yield up to 60 gallons per minute, but the gravels grade into clay and silt of the tidal marshes where the yield drops to less than 2 gallons per minute. The dune sands and older beach sands of Point Reyes Beach appear to form good porous and permeable ground-water reservoirs.

Table 14. Point Reyes Peninsula ranches and localities.

| Name used this report |

Name used by Gilbert (1908) |

Other names | Latitude and Longitude | |

| N Jat | W long | |||

| AT&T radio station | "Post office" | E. Gallagher | 38°05'31" | 122°57'16" |

| Bear Valley Ranch | Skinner, W.D. | Howard, Kelham, Abbott, W.H., Seashore Headquarters | 38°02'39" | 122°47'50" |

| Beisler | Beisler | Part of Hagmaier Dream Farm | 37°58'28" | 122°44'07" |

| Bender | 38°05'21" | 122°50'40" | ||

| Clam Patch | Clam Patch | 37°54'09" | 122°41'19" | |

| Glenn Ranch | Part of Kelham | 37°59'25" | 122°47'17" | |

| Grossi (A.) Ranch | 38°07'01" | 122°55'31" | ||

| Grossi (D.) Ranch | 38°06'32" | 122°54'12" | ||

| Hagmaier Ranch | Bondietti | 37°58'16" | 122°43'47" | |

| Heims Ranch | 38°05'24" | 122°54'45" | ||

| Hall Ranch | 38°02'09" | 122°57'42" | ||

| Hamilton | Hamilton (barn) | Willow Point | 38°05'24" | 122°50'33" |

| Home Ranch | Murphy | 38°04'22" | 122°54'19" | |

| Kehoe Ranch | 38°09'35" | 122°56'12" | ||

| Laguna Ranch | Marshall | 38°02'39" | 122°51'39" | |

| Lagunitas Creek | Papermill Creek | |||

| Lake Ranch | "Seven Lakes" | 37°56'54" | 122°45'25" | |

| Lockhart Ranch | Sunshine | Sunny Side | 38°03'40" | 122°50'01" |

| McClure, J., Ranch | 38°08'06" | 122°56'22" | ||

| Mendoza Ranch | 38°00'56" | 122°59'16" | ||

| Molseed Ranch | Claussen | Marvin Nunes | 38°03'30" | 122°58'14" |

| Muddy Hollow Ranch | 38°02'58" | 122°52'07" | ||

| Noren residence | 38°03'36" | 122°49'01" | ||

| Nunes, George, Ranch | (ex Mendoza) | 38°00'01" | 122°59'39" | |

| Ottinger Ranch | Vision | 38°06'28" | 122°52'53" | |

| Palomarin | Religious Colony, Church of Golden Rule | 37°56'06" | 122°44'51" | |

| Pepper Island | Kent Island | |||

| Pierce, Lower, Ranch | McClure | 38°13'26" | 122°58'39" | |

| Pierce, Upper, Ranch | McClure | 38°11'25" | 122°57'12" | |

| Pig Ranch | Pig Farm | 37°59'51" | 122°49'11" | |

| RCA radio station | Lunny, McClure | 38°05'44" | 122°56'45" | |

| Righetti Ranch | Southworth | Riverside | 37°56'42" | 122°42'28" |

| Rogers Ranch | "Old blacksmith shop"; (ex Grossi) | 38°05'37" | 122°54'50" | |

| Sky Farm | Part of Kelham | 38°02'24" | 122°49'36" | |

| Spaletta Ranch | T. Gallagher | 38°02'27" | 122°58'47" | |

| Steele Ranch | Marquis | 37°56'00" | 122°41'54" | |

| Stewart, Boyd, Ranch | Dickson Ranch | "Woodside", Olds | 38°00'32" | 122°45'46" |

| Stinson Beach | Willow Camp | |||

| Texeira Ranch | Strain, E.R. | 37°57'12" | 122°42'51" | |

| Truttman | Bloom | 38°01'32" | 122°46'32" | |

| U Ranch | Part of Kelham Olema Ranch | 38°01'06" | 122°51'13" | |

| Vedanta Retreat | Payne Shafter Place | "The Oaks" | 38°02'09" | 122°47'25" |

| Wildcat Ranch | Bolema Club | 37°58'13" | 122°47'18" | |

| Wilkins | McCurdy | 37°56'11" | 122°41'54" | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/ca/cdmg-bul-202/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2007