|

Texas Bureau of Economic Geology

The Big Bend of the Rio Grande: A Guide to the Rocks, Geologic History, and Settlers of the Area of Big Bend National Park |

INTRODUCTION

The Big Bend of the Rio Grande

A Guide to the Rocks, Landscape, Geologic History, and

Settlers of the Area of Big Bend National Park

Ross A. Maxwell

The scene is set.—According to Indian legend, when the Great Creator made the earth and had finished placing the stars in the sky, the birds in the air, and the fish in the sea, there was a large pile of rejected stony materials left over. Finished with His job, He threw this into one heap and made the Big Bend.

The rocks are strangely mixed up, most of the strata are lopsided or standing on end, and some of the mountains are turned upside down and piled where they do not appear to fit. Along the Rio Grande are deep, yawning canyons and above them are mountain peaks that rise above the flats like giant sentinels. The Chisos Mountains, with their ghost-like peaks, guard the northern approach to the river, and the Sierra del Carmen range, overlooking the southern bank, rises as a sheer wall to heights that dwarf the Palisades of the Hudson.

Mexicans and Anglo-Saxons both have taken part in settling the area. In the early days large herds of cattle moved about on a free range, dependent upon the location of grass and water; herds were driven in both directions across the Rio Grande without regulations imposed by either government.

The big adventures in the settling of this vast frontier area are over, but history here is only yesterday and is close enough to intrigue both tourists and local inhabitants. It was the idea of preserving the area with its unique traditions that led to the proposal in 1935 to set aside as a National Park the southern portion of the Big Bend country, which was purchased by the State of Texas and deeded to the Federal government. Because of the immensity of the area and the inaccessibility of parts of it, tourists cannot hope to explore the Big Bend completely. But the adventuresome and scenery-loving traveler will be captured by the spell of the place on just a short excursion into the area.

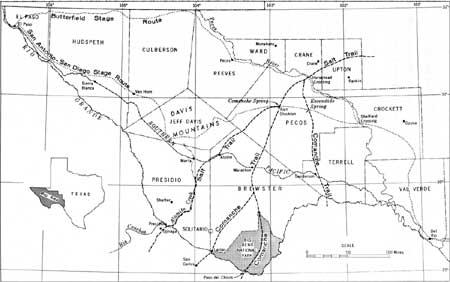

The name Big Bend is somewhat loosely applied to the area surrounded on three sides by the Rio Grande, where this great river swings deeply southward into Mexico approximately halfway in its course between El Paso and Laredo. The Rio Grande also marks the boundary between the United States of Mexico and the United States of America. All of the area in Brewster and Presidio counties south of the Southern Pacific Railway is commonly considered as the Big Bend country. Big Bend National Park lies within the southernmost tip of the area and is only a portion of the Big Bend country (fig. 1).

|

| FIG. 1. Map of West Texas showing some of the early trails and Big Bend National Park. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Park includes both lowland and mountain environments; it was selected for a National Park because of scenery, geologic features, and the display of southwestern plant and animal communities. Big Bend National Park includes 708,281 acres of Federally-owned land; it is not completely developed. There are no railroads and only recently has it been served by paved highways. It is a harsh land. Although there are many canyons, broad stream valleys, and great cobble-choked arroyos, only a few are permanently occupied by running water. Most of them are mainly the result of past erosion in a wetter time. The present terrain gives the impression that when Mother Nature had finished cutting the canyons and carving the many topographic features, she turned off the water supply.

The desert climate provides a botanical assemblage that is strange, weird, and totally different from the habitats of the more thickly populated areas in Texas. There are no true forests except on the tops of the highest peaks, no dashing trout streams, and most of the surface is but scantily clothed by desert vegetation. Most plants are armored with thorns and spines that wound, catch, and hold or otherwise retard the movements of any individual who may choose to venture from the trails, first made by early nomads and later used by the Apache and Comanche Indians. Many of these routes have now been widened, first by the Spanish Conquistadors, next by the Mexican settlers, later by freight lines, overland stage, mail routes, cowboys, and cattle drives, and finally by the various highway organizations that have graded or surfaced the roads and made them available to modern automobiles (fig. 2). The country's harsh terrain, scrubby vegetation, scarcity of water, and severe climate are probably the chief reasons why the Big Bend area is one of the nation's last frontiers. It was a natural haven for the outlaw who traveled light and could lose himself in the natural rock shelters of the desolate region (fig. 3). Only the more hardy souls tried to farm and ranch in the area. They learned that normally the springs are on the hillsides and the roots of the scrub vegetation are larger than the tops. A common saying in the Big Bend is that it is usually necessary to dig for wood and climb for water.

|

| FIG. 2. The Texas Highway Department's first camp in the area that is now Big Bend National Park (1936). The landscape scar where this camp once stood is on the east side of the present Park road near the top of Hannold Hill northeast of the Chisos Mountains. Personnel from this camp maintained the Marathon entrance road until the end of 1939. |

|

| FIG. 3. A traveler's lonely camp in the Big Bend country. All soon learn to fold up the blankets to prevent condensation of moisture else they will sleep in a wet bed the next time the bedding is used. |

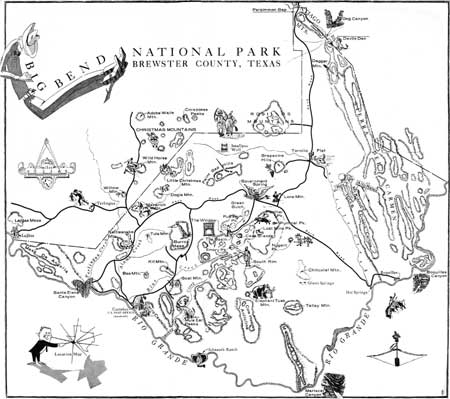

The erosion that sculptured the landscape in the Big Bend left many topographic features to be named by the early Spanish explorers and by Mexican and Anglo-Saxon settlers (fig. 4) (in pocket). Many of the names are Spanish. They include Mesa de Anguila, translated Mesa of the Eels, although some have suggested that the word "Anguila" is an English corruption for the Spanish angel (Mesa of the Angels) or for aguila (Mesa of the Eagles); Santa Elena Canyon (Saint Helen's Canyon); Terlingua (English corruption for tres lenguas, "three tongues" or "three languages"); Punta de la Sierra (Point of the Mountain); Casa Grande ("the big house"); and even the name "Chisos" (Chisos Mountains) has been interpreted by some to mean "phantom," "ghost," "spirit, spear-head," or a small band of Chizos Indians who migrated from Chihuahua and lived in the Chisos Mountains. Features named for early settlers or prominent people include Ward Mountain, Pulliam Peak, Vernon Bailey Peak, Roger Toll Peak, George Wright Peak, Emory Peak, Carter Peak, Hayes Ridge, Dominguez Mountain, Fisk Canyon, Stewart Peak, and Banta Shut-In. Margaret Basin and Sue Peaks are named for relatives of an early surveyor. Government Spring was a camp where government surveyors headquartered. Captain Neville of Texas Ranger fame gave his name to Neville Spring. Roy's Peak and Stillwell Mountain were named for one of the early ranching families. The livestock industry was recognized by such features as Maverick Mountain, Cow Heaven Mountain, Dogie Mountain, and Burro Mesa. The predatory cat gave its name to Panther Peak and Panther Spring, the reptile to Rattlesnake Mountain, and the dreaded disease to Smallpox Well. Fresno (ash), Alamo (cottonwood), Willow, and Cottonwood Creeks, and Ash and Oak Springs were named for trees; Grapevine Hills for the vine which once grew there in abundance; Paint Gap Hills and Rosillos Mountains for color. The holiday season was commemorated by the Christmas Mountains and royalty by Crown Mountain (P1. I, in pocket).

|

| FIG. 4. Big Bend National Park with principal geologic and topographic features and roads. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Men inhabited the Big Bend area long before the coming of the Spaniards. Some have called the early inhabitants the "Big Bend Basket Makers," as their way of life resembled that of the Basket Makers to the northwest. They wove baskets, sandals, and other objects from native plants. They undoubtedly lived in caves and, in later periods, in pit houses. They raised corn and possibly also squash and beans and cooked their food. They hunted game, using darts with spear-throwing sticks in early times and, later, bows and arrows; no doubt they also fished (Horgan, 1954). The relation between this early culture and later ones is not clear. Historical documents show the characteristics of the plains tribes that were in this area during the seventeenth century. These tribes included various branches of the Eastern Apaches, including Lipan and Mescalero. One small group in this general region was known as the Chizos tribe. It is from this sub-tribe that the chieftain Alsate originated. He dominated the area until a stronger people forced him to retreat to the Chisos Mountains.

Alvar Nuñnez Cabeza de Vaca, the Spanish adventurer, was the first white man to visit the Big Bend country (Raht, 1919, p. 1). He was a member of the Governor Pánfilo de Narvaez expedition which sailed from the port of San Lucar de Barrameda (Spain) on June 27, 1527, with orders from King Charles V to explore and conquer Florida. The ships were lost on the Florida coast but after building five barges from roughly hewn timber and scrap, the expedition sailed from Mobile Bay in search of a Spanish settlement known as Panuco, near the present seaport of Tampico, Mexico. The barges were wrecked in a storm off Galveston Island (November 6, 1528), only a small remnant of the force reached land, and most of the survivors soon died of starvation or exposure to cold weather (Kilman, 1959, p. 2).

De Vaca was one of the survivors of the expedition. He was made captive by the Indians and remained a slave for six years. During the period of his captivity, he learned many Indian customs, became a trader and medicine man, and during his wanderings learned that there were other Spanish captives in nearby Indian villages. In time he communicated with his country men and they planned an escape. After the escape, he and his three followers traveled from one Indian village to another, sometimes as slaves, at other times as medicine men or gods. He headed west, hoping to reach the Spanish colonies known to exist in Sinaloa, Mexico, on the Pacific coast. However, the westward journey was deflected northwest because it was necessary to detour around canyons and find fords in the rivers. Two of the party could not swim. The northwesterly course led de Vaca far inland from his intended route; he crossed the Big Bend country about 43 years after Columbus discovered America.1

1The fate of the Narvaez expedition, the barge wreck off Galveston Island, and de Vaca's capture, slavery, success as a medicine man, escape, and travel toward the west are discussed in more detail by Kilman (1959, pp. 1-36) and Raht (1919, pp. 1-26).

De Vaca's description of the physical features in the Big Bend is vague. He did mention a river, presumably the Pecos, that he crossed before marching southwest across a wind-swept plain that was barren of game and water. Toward the southwest he saw lofty mountains of the northern Big Bend country and on reaching them, found that in the mountains there were magnificent valleys with game and water. Presumably he followed what in later years became known as the great Indian trail crossing the Pecos River at either the Horsehead or Sheffield Crossing (fig. 1), thence west to Comanche Spring at Fort Stockton, through the Davis Mountains, southward to Burgess waterhole near Alpine, and southwestward to Alamito Creek, following that valley southward to the Rio Grande near Presidio. Here he found the Indians living in fixed settlements along the river and cultivating small patches of corn, beans, and pumpkins (Raht, 1919, pp. 1-26).

He wrote the first description of the Big Bend but it was not a scientific description, nor did he find the mineral wealth for which the early Spanish explorers were continually searching. He did find indications of metal, for along the journey he received gifts of copper, silver, and cinnabar, but it was more than two centuries later before the silver at Shafter (Presidio County) and cinnabar in the Terlingua district (Brewster County) were discovered (fig. 1).

De Vaca entered the Big Bend from the east; Antonio de Espejo, the second and last of the early Spanish explorers to cross the area, came from the north. His expedition began (November 10, 1582) at Valle de San Bartolome, Mexico (east of Chihuahua city); he pushed northward to the junction of the Rio Conchos and Rio Grande near Ojinaga opposite Presidio, Texas. Here he found the Indians, whom he called Jumanos, dwelling in permanent pueblos, subsisting on game, fish, corn, wheat, maize, gourds, and melons that were cultivated in small patches along the Rio Grande. He traveled up the Rio Grande, which he named Guadalquiver from a river in Spain, to New Mexico, thence east to the Pecos River, which he named Rio de las Vacas (River of the Cows) for the buffalo found in that vicinity (Raht, 1919, p. 32), and thence down the Pecos to the crossing of a great Indian trail (fig. 1). Here he met three Jumanos Indians from the pueblo near Ojinaga who guided him across the Big Bend, probably by a route similar to that taken by de Vaca.

The Spanish explorers were lured by the tales of cities whose streets were paved with gold, and their imaginations were fired to such an extent that they were willing to endure almost unbelievable hardships to realize their dreams. The monks and lay brothers of the Franciscan and Jesuit brotherhoods were also interested by the reports of wealth but they dreamed mostly of spiritual conquests. Credulous as the Spaniards were of every tale told them by the Indians, not one of the expeditions sought to settle the Big Bend. Except for de Vaca and Espejo, the tide of Spanish explorations split around the rugged mountains like "coyotes circling a wolf pack devouring a kill," and for two centuries the trickle of people ebbed and flowed to either side of the Big Bend (Raht, 1919, pp. 27-38). It remained for other peoples—the Latin-Americans and Anglo-Saxon Americans—to conquer first the Indians, then the outlaw bands, and to find the mineral wealth and settle the area. The folklore abounds with tales of Indians on hunting and war treks and of bandit raids, cattle rustling, horse stealing, murders, lawlessness, lost mines, and buried treasure.

Acknowledgments.—The writer is in debted to many individuals who have furnished historical data for the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, narrated incidents of local interest, and given accounts of the legends that have been handed down through the generations.

Special recognition is given to Lloyd Wade, Marathon, Texas, who was a co-worker and rancher in the Park; R. L. (Bob) Cartledge, Austin, Texas, who was a resident and business man in the Big Bend; the late E. E. Townsend, who is credited with originating the idea for a National Park; Elmo Johnson, Sonora, Texas, who operated the Johnson's ranch trading post; J. O. Langford, Kerrville, Texas, who built the Hot Springs trading post, and the late Margaret (Maggy) Smith, who operated that trading post from 1942 to 1952; the late W. T. (Waddy) Burnham, the late Sam Nail, and the late Ira Hector, all former ranchers in the Park; the late Ben Ordones, Macario Hinojos, Terlingua, Texas, Petra Alvarado, Lajitas, Texas, and others of Latin-American descent, who furnished most of the legends and told of the uses of the plants by the native healers; the late W. P. Webb, who related many of the historical events; and B. H. Warnoch, Alpine, Texas, and E. O. Sperry, College Station, Texas, who helped in identification of the local vegetation; E. K. Reed, National Park Service, Santa Fe, New Mexico, who made an archeological study in the Park in 1936 at the same time the writer began mapping the geology; C. P. Ross, then of the U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C., who introduced the writer to the Big Bend geology; the late C. N. Gould, who supervised some of the early geological work; the late J. T. Lonsdale, who was a co-worker in later geological investigations; the Park Superintendents and members of their staff, who cooperated fully and aided the writer in many ways.

Part or all of the manuscript was critically read by B. H. Warnoch, Department of Biology, Sul Ross State College, Alpine, Texas; D. B. Evans, formerly Chief Park Naturalist, Big Bend National Park; S. C. Joseph, formerly Superintendent of Big Bend National Park; Helen Maxwell, D. H. Eargle, F. D. Quinn, and R. L. Cartledge, Austin, Texas; and Thomas M. Runge, M. D., Austin, Texas, who read the section on native healers.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/tx/1968-7/intro.htm

Last Updated: 08-May-2007