|

Texas Bureau of Economic Geology

Padre Island National Seashore: A Guide to the Geology, Natural Environments, and History of a Texas Barrier Island |

INTRODUCTION

Stretching 113 miles under the South Texas sun is the longest barrier island in the United States. This is Padre Island — where shipwrecked Spaniards were once pursued and massacred by fierce Karankawa Indians; where Pat Dunn's vaqueros herded thousands of cattle in preparation for trips to the market; and where now almost a million visitors every year spread out along the miles of sandy and shelly beaches to enjoy the untamed beauty of Padre Island National Seashore.

To those experiencing the serenity and solitude of Padre's primitive stretches, the island may seem forever unchanging. But geologically, Padre is actually a dynamic system of environments that change almost continuously. The face of Padre is shaped by the day-to-day action of the wind, currents, waves, and tides. Even more important, large storms, especially hurricanes, produce dramatic changes on the island. Padre Island can be thought of as a natural laboratory where complex interaction of the wind, land, and sea produces unique features and environments that can be examined and questioned by all who visit the National Seashore.

PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE GUIDE

The Guidebook

This guide to Padre Island National Seashore describes and explains island and lagoon environments, the active processes that constantly change the face of Padre, and natural records left by those processes. A road log for a short field trip directs readers to these environments and effects of the active processes. The guide also presents summaries of the geologic origin and history of Padre, as well as the history of human use of the island and interaction with the natural environments.

Because this book is designed for an audience with a wide range of interests, education, and experience, the text should prove useful and interesting to geologists and students as well as to the casual island observer. Although this guide is essentially nontechnical, it is necessary to include some terms that are probably unfamiliar to many readers. These terms are explained on first use within the text and also in a glossary at the end of this guidebook.

The Geology and Natural Environments Map

A colored map of the National Seashore (pl. I, in pocket) illustrates the present geologic and man-made environments of the island and lagoon. Natural environments were mapped on the basis of origin, landforms, vegetation, and active processes. Several special features ensure that the map can be read easily by geologists and non-geologists alike. To aid those unfamiliar with reading maps, a detailed explanation of the map and its use is presented in a later section (see p. 10-12).

Padre is a barrier island with rapidly changing environments. Despite inevitable natural changes on the island, the Geology and Natural Environments Map will remain a useful record from which to monitor future changes. The map can also serve as an illustration, or model, of those environmental relationships that do not change and that can be observed repeatedly on Padre and on similar barrier islands.

GENERAL SETTING

Location

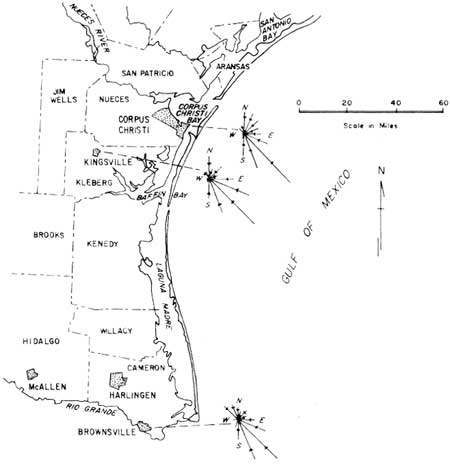

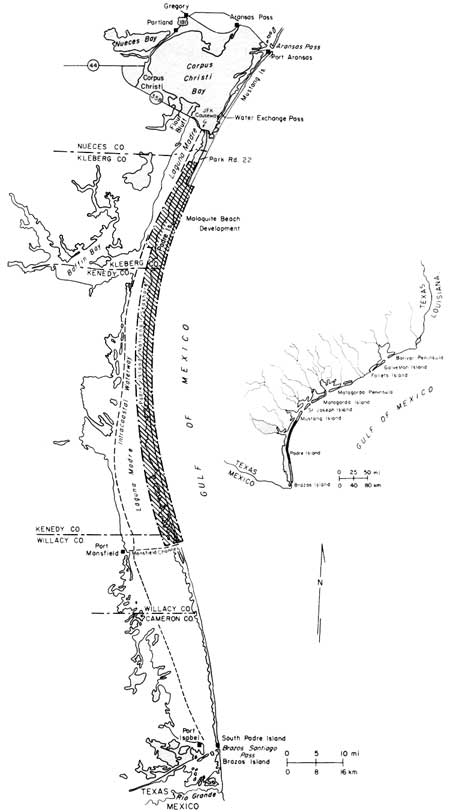

Padre Island is one of the southernmost links in the chain of barrier islands and peninsulas along the curving Texas coastline (fig. 1). Broken only by a man made channel, Mansfield Channel, this island extends southward from Corpus Christi almost to Mexico. Padre Island is separated by Brazos Santiago Pass from Brazos Island, which lies at the southern end of the chain. Corpus Christi Pass, a natural pass to the north, once separated Padre Island from Mustang Island but is now filled so that the two islands are joined.

|

| Figure 1. Index and location maps for Padre Island and the surrounding area. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Although an attractive site for resorts, most of Padre has remained undeveloped. In 1962, the United States Congress passed legislation establishing Padre Island National Seashore; this 80-mile segment of Padre Island will preserve the natural qualities of this pristine island (fig. 1).

Physiography and General Geology

PADRE ISLAND

Geologically, Padre Island is very young; its oldest deposits are only several thousand years old. Waves and currents in the Gulf of Mexico piled sand into a barrier island separated from the Texas mainland by a lagoon, Laguna Madre. Most of Padre Island is less than 20 feet above mean sea level. However, the island's highest points, along the fore-island dune ridge, reach up to 50 feet above sea level. Nearest equivalent elevations are about 25 miles inland.

Prevailing southeasterly winds from the Gulf of Mexico heap beach sand into high foredunes. In some places, the onshore wind may blow loose sand from the foredunes and beach across the flats beyond. Active sand dunes march across the island, smothering vegetation in their paths and leaving barren sandflats in their wakes. In other places, vegetation may win a battle of its own and stabilize the blowing sand by binding it with roots and vines. Slower daily movements of the sand and stabilizing effects of vegetation are interrupted occasionally by the brutal force of hurricane winds, waves, and tides. During storms, beaches are eroded, vegetation is ripped up, dunes are flattened, and channels are scoured across the island.

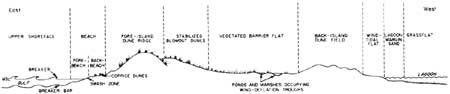

These natural processes at work on Padre have produced a predictable pattern of environments across the island, which, within the National Seashore, varies in width from about 1,000 yards to about 2.5 miles. A common sequence of environments from the Gulf to Laguna Madre includes the sand and shell beach; a stable ridge of fore-island dunes; vegetated flats with scattered, stabilized, grass-covered dunes; the barren, shifting sands of back-island dune fields; and the featureless plains of wind-tidal flats (fig. 2).

Not only do environments change across the island, but also considerable variation occurs within each environment along the length of the island. For example, the beach changes from a gently sloping sand beach on north Padre, to the steeper Little Shell and Big Shell Beaches on central Padre, to the mixed sand and shell beaches on south Padre. The fore-island dune ridge is highest and most continuous adjacent to the shell beaches. However, in the southern parts of the Seashore, the ridge is absent or present only as short segments of low foredune ridges because of (1) higher shoreline erosion rates, which reduce the amount of sediment available for dune construction, and (2) a drier climate and consequently much less vegetation to bind the sand. Without the protective natural barricade provided by the dune ridge, the southern parts of the island are much more susceptible to breaching during the fury of hurricanes. Therefore, storm washover channels are much more prominent on the southern part of Padre Island.

LAGUNA MADRE

Laguna Madre, separating Padre Island from the Texas mainland, is locked in by the barrier island. Consequently, circulation of seawater in and out of the lagoon is highly restricted. The combination of a high rate of evaporation under the hot Texas sun and little mixing with either freshwater or normal seawater has made Laguna Madre extremely salty.

The maximum width of the lagoon is approximately 10 miles. In many places, however, lagoon width fluctuates considerably with the height of wind-generated tides. The lagoon is widest during highest wind tides, which produce maximum flooding of the vast tidal flats.

Like the island environments, the environments of Laguna Madre vary considerably. Within the National Seashore, the northern part of the lagoon is occupied largely by grassflats having an average water depth of about 3 feet. These grassflats are environments of very high biologic activity, serving as spawning grounds for a number of fish, clams, and snails.

The shallowest parts of the lagoon lie in the central part of the National Seashore. These areas are known as Middle Ground and the Land-Cut Area, where the Intracoastal Waterway was dredged through the rarely flooded wind-tidal flats (pl. I). The Hole, which lies between Middle Ground and the Land-Cut Area, is not really much of a hole; its average depths are only 1 to 2 feet. This "hole" is occupied mostly by flats supporting shoalgrass and algae. The deepest parts of the lagoon are south of the Land-Cut Area, where the muddy sand bottoms lie at depths as great as 8 feet (pl. I).

Two small natural islands in Laguna Madre are unique environments within the National Seashore. North and South Bird Islands (pl. I), each a series of sand berms or ridges, have become important bird rookeries. Some of the man-made spoil islands along the Intracoastal Waterway are also nesting grounds for a variety of birds.

Climate

The climate of Padre Island is subtropical and semiarid — in other words, generally hot and dry. Summers are long and hot, and winters are relatively short and mild. Spring and fall are merely transitional periods.

PRECIPITATION AND EVAPORATION

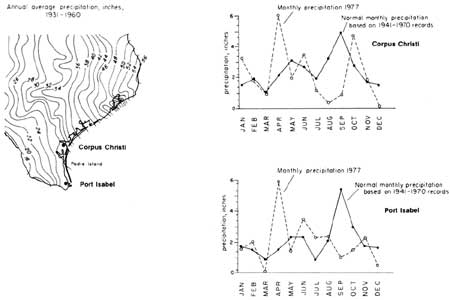

Average annual rainfall ranges from approximately 29 inches at the northern end of the island to approximately 26 inches at the southern end (fig. 3). Evaporation rates increase southward along the island. The combination of lower annual rainfall and higher evaporation rates for south Padre results in a drier climate and a different set of environments from those on north Padre.

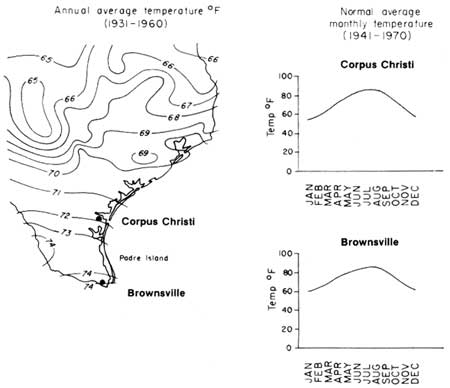

TEMPERATURE

The higher rate of evaporation in the south results from higher mean annual temperature (fig. 4). Average temperatures range from approximately 72°F in the north to approximately 74°F in the south. Temperatures on the island are moderated by tropical maritime air coming off the Gulf of Mexico. Although temperatures on the nearby Texas mainland commonly exceed 100°F during the summer, island temperatures are rarely above 95°F. At Corpus Christi, on the mainland near the northern end of the island, the temperature falls to freezing or below about 10 times a year (Dahl and others, 1974). Freezing temperatures, however, are less frequent southward and are rare on Padre Island.

WINDS

The prevailing winds (winds that blow across Padre most frequently) are southeasterlies (fig. 5). Winds are mostly from the southeast in the summer months, or from about May through September. However, during the winter, from December through February, wind direction fluctuates between northerly and southeasterly, as a series of "northers," or cold polar fronts, pass through the coastal area.

Direction is not the only important aspect of the wind that influences island and lagoon environments. The ability of the wind to transport sand and generate currents, waves, and tides depends on the velocity and duration of the wind. Dominant winds, capable of transporting sand, are from the north to north-northeast and from the south-southeast to southeast. Winds sweeping across Padre reach velocities high enough to transport sand about 85 percent of the time (Dahl and others, 1974).

Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

The average climatic conditions previously described are punctuated by fierce tropical storms and hurricanes. Tropical storms become hurricanes when the wind velocity exceeds 74 miles per hour. Wind velocities in the most intense hurricanes may exceed 200 miles per hour. The cyclonic wind circulation of these storms, which may be hundreds of miles in diameter, has a counterclockwise motion in the Northern Hemisphere. The storms are characterized by very low barometric pressure, with the lowest pressure in the central calm region, or eye, of the storm. Hurricanes may deposit tens of inches of rain and commonly spawn tornadoes, contributing to their destructiveness (see table 1, p. 39).

Tropical cyclones (tropical storms and hurricanes) strike the Texas coast at an average rate of 0.67 storms per year (Hayes, 1965). In other words, two storms strike the coast every three years. Most hurricanes hitting the Texas coast originate in the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The hurricane season actually begins in late spring, but the prime time for tropical cyclone development is late summer and early fall, or from August through October. One of the largest and most destructive recorded storms to strike the Gulf Coast was Hurricane Carla, which formed in the Caribbean in early September, 1961. Although the eye of Carla struck the central section of the Texas coast in the Port O'Connor area, hurricane winds affected almost the entire Texas coast and part of Louisiana. Maximum wind velocity in the storm was estimated to be about 175 miles per hour (Hayes, 1967).

The destruction caused by hurricanes can be tremendous. On the open sea not even the largest vessels are safe. Once these storms strike land, they may move hundreds of miles inland before finally dissipating. Within the United States alone, hurricanes have caused millions of dollars' worth of property damage and have taken thousands of lives. The high winds are not the only direct, damaging forces of the storms; many times the storm tides, huge waves, strong currents, and heavy rainfall accompanying hurricanes have even greater impact. A section of this guide describes hurricanes and their effects on Padre Island (see p. 38).

ESTABLISHMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF PADRE ISLAND NATIONAL SEASHORE

Creation of a National Seashore

In 1954, the U.S. National Park Service surveyed the 3,700 miles of U.S. coastline and discovered that only 6.5 percent of the coastline was reserved for public recreation. The Park Service recommended that national parks be created in three coastal areas: (1) Point Reyes, California, (2) Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and (3) Padre Island, Texas. Legislative action, however, was necessary to acquire lands for the national parks, or seashores, as they were later named. Senator Ralph Yarborough introduced the first Padre Island bill to the U.S. Congress in 1958. After several years of hearings, Congress, on September 28, 1962, passed the law establishing Padre Island National Seashore.

The enabling legislation, Public Law 87-712, stated the purpose of Padre Island National Seashore: "to save and preserve, for purposes of public recreation, benefit, and inspiration, a portion of the diminishing seashore of the United States that remains undeveloped. Indeed, Padre Island is the largest stretch of undeveloped ocean beach in the United States.

The legislative act of 1962 authorized no more than $5 million for purchase of land for the newly created National Seashore. Subsequent legislation in 1968 and 1969, however, provided more money for land acquisition. The Federal Government has spent almost $16 million for land within Padre Island National Seashore.

The 1962 legislation also set the boundaries of the Seashore. Except for an extension of the Seashore south of Mansfield Channel, these boundaries are shown on the Geology and Natural Environments Map (pl. I). South of Mansfield Channel, the National Seashore includes only 2 small pieces of land totaling 18 acres, plus 11.5 miles of beach donated by the State of Texas. However, a proposed boundary change for southern Padre Island National Seashore is described in the National Park Service Master Plan (1973). This will provide space for recreational facilities on the south side of Mansfield Channel. The Park Service will exchange its land south of Mansfield Channel for land adjacent to the channel. The section of beach donated by the State and lying south of the channel will be returned to the State.

U.S. National Park Service and Seashore Management

Padre Island National Seashore is administered by the U.S. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Park Service headquarters are located in Corpus Christi on South Padre Island Drive, the main access route to the Seashore.

Management objectives outlined by the National Park Service in its Master Plan for the Seashore (1973) are (1) to serve the visitor, (2) to preserve the resource, and (3) to administer the area. The Park Service serves Seashore visitors by providing information, by maintaining park facilities and roads, and by aiding those in need of assistance. Also for the benefit of visitors, the Park Service has established certain regulations governing camping, swimming, fishing, hiking, driving, boating, and other activities. Information concerning these guidelines, which help assure the greatest degree of safety and enjoyment for Seashore visitors and protection of natural environments, may be obtained either at Park Service headquarters or at the Ranger Station on the island.

The National Park Service is responsible for the development and maintenance of all facilities within the National Seashore, except for oil company facilities, roads, and channels. In addition, the Park Service cooperates with the State of Texas and the National Audubon Society in managing wildlife resources and works closely with the U.S. Coast Guard in rescue operations.

Visitor Facilities

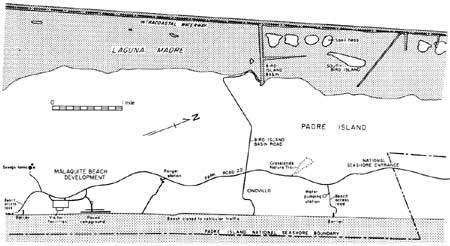

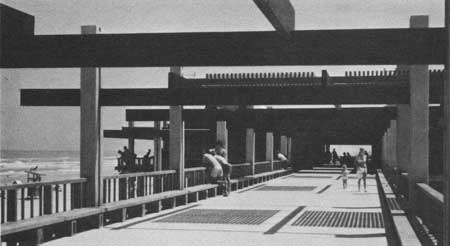

Visitor facilities at Malaquite Beach are located near the end of Park Road 22 approximately 5 miles south of the Seashore entrance (fig. 6). This beach development (pl. I, photograph M4, and fig. 7) includes a snackbar, a gift shop, free showers, locker rooms, observation decks, and a large, paved parking lot. Although wells and tanks on the island provided fresh water for ranching operations, water is now piped to the Malaquite Beach development from Corpus Christi.

|

| Figure 6. index map of the northern part of Padre island National Seashore. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 7. Observation deck and walkway at Malaquite Beach visitor facilities. |

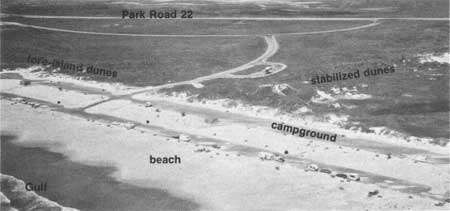

A tower near the main facility provides an observation deck and water storage below. A few hundred yards north of the visitor facilities is a paved campground (fig. 8), accessible from Park Road 22. The campground provides numerous sites for trailers and recreational vehicles. The beach in the Malaquite area is regularly cleared and maintained; it is closed to vehicular traffic between the two beach access roads, a distance of about 4.5 miles.

|

| Figure 8. Paved campground just north of Malaquite Beach visitor facilities. The campground, located on the backbeach, was extensively damaged during Hurricane Allen in August 1980 (see p. 73). The above photograph was taken before the storm. |

Plans for new developments within the National Seashore include expanding the present Malaquite Beach facilities, creating access to Laguna Madre in the Bird Island Basin area, extending the road system to Yarborough Pass, and constructing recreational facilities at Mansfield Channel. Future developments will provide easier access and service to remote parts of the island but will be designed to maintain the primitive nature of the beach and interior lands. The U.S. National Park Service Master Plan (1973) for Padre Island National Seashore, available at Park Service headquarters and the Ranger Station, describes these and other proposed changes.

Access to Island and Lagoon Environments

ISLAND ACCESS

Roads — Visitors may reach North Padre Island by way of Mustang Island on the north or via the John F. Kennedy Causeway, which crosses Laguna Madre from Flour Bluff to Padre Island (fig. 1). The road leading into the National Seashore is Park Road 22; it is a paved, two-lane highway winding down the middle of the island. Park Road 22 ends as a beach access road about 5.5 miles south of the Seashore entrance (fig. 6). Another beach access road branches from Park Road 22 about 1 mile south of the Seashore entrance. The beach may be reached also by taking the road to the paved campground just north of the Malaquite visitor facilities. The Bird Island Basin road, intersecting Park Road 22 about 2 miles south of the Seashore entrance, provides the easiest access to Laguna Madre.

Crossing the island are several sand or shell-covered roads, some of which were built and are maintained by oil companies. Most of these roads require a four-wheel-drive vehicle and often are impassable, especially after rains.

Beach Travel — Vehicular travel is permitted along the entire length of the National Seashore beach except between the two main beach access roads. Visitors can travel on the beach southward as far as Mansfield Channel, which is not bridged. Areas south of the channel can be reached only from the southern end of the island via Port Isabel.

Special vehicles are not necessary for travel on the beach to a point about 5 miles south of the end of Park Road 22. Southward from that point, four-wheel-drive vehicles are required. The point is marked on the beach by a warning sign (fig. 9 and pl. I, grid K-4). Even with four-wheel-drive vehicles, travelers run the risk of getting stuck, especially in the slippery, loose shell material on Big Shell and Little Shell Beaches. It is recommended that all beach travelers carry shovels, jacks, and tow chains.

|

| Figure 9. Four-wheel-drive warning sign (pl. I, grid K-4). Beach conditions, in particular the slippery, loose shell surface material, make vehicular travel possible only with four-wheel drive from this point south. View is to the south. |

To aid beach travel and rescue operations, large beach markers show the cumulative mileage from the south beach access road (end of Park Road 22) at approximately 5-mile intervals (fig. 10). Locations of these markers as of 1977 are indicated on the Geology and Natural Environments Map (pl. I). Where the markers are destroyed by storms or removed in some other way, however, their reestablished locations may not coincide with the original locations as plotted on plate I.

|

| Figure 10. Beach marker showing the approximate mileage from the south beach access road near Malaquite Beach. Locations of beach mileage markers as of 1977 are plotted on plate I. Marker locations are subject to change, however, if markers are destroyed by storms or other means. View is to the south. |

ACCESS TO LAGOON ENVIRONMENTS

Except along the Intracoastal Waterway or Mansfield Channel, shallow water depths restrict boating on Laguna Madre to small pleasure and fishing boats. In the northern part of the Seashore, the lagoon is deep enough during high tides to allow small boats to land on the lagoonal shores of the island. A launching facility at Bird Island Basin allows access to northern Laguna Madre from the island. However, only specialized craft, such as air boats, can navigate many areas of the lagoon. Some large areas of the lagoon are unsafe for any type of boat. In those areas, boats may become stranded during rapid lowering of water level, produced by unpredictable and irregular wind-generated tides.

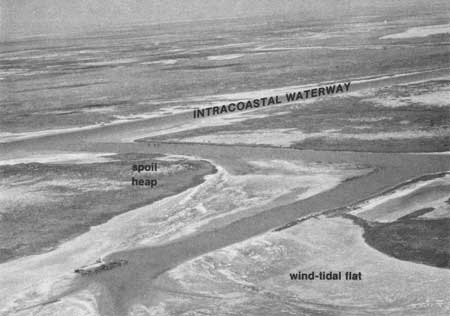

Gulf Intracoastal Waterway — The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway is a system of dredged channels providing an inland shipping route along the Gulf Coast of the United States. The principal use of the Waterway in the South Texas area is for commercial barge operations (pl. I, L7 photograph), but fishing and pleasure boats also use it heavily. The section of the Intracoastal Waterway through Laguna Madre on or near the western edge of the National Seashore (fig. 11) was completed in 1949. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains the canal's present depth of 12 feet and width of 125 feet through periodic dredging. Frequency of dredging near the National Seashore varies from 15 months to 5 years (Herbich, 1975).

|

| Figure 11. Intracoastal Waterway, approximately 12 feet deep, paralleled by a row of spoil heaps (pl. I, grids P-7 and O-7). in this area the boundary of the National Seashore does not coincide with the Waterway but rather lies farther to the east (left). View is to the south. |

A system of buoys and beacons aids navigation along the Intracoastal Waterway. These navigation markers are plotted and explained on nautical charts prepared by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In addition, the locations of some of these markers are shown on the Geology and Natural Environments Map (pl. I).

Numerous small channels (fig. 12) branching from the Intracoastal Waterway (pl. I) were dredged to provide access to oil and gas operations. Many of these canals are now abandoned and have filled with mud and fine organic material.

|

| Figure 12. Petroleum company service channel dredged from the Intracoastal Waterway to provide access to a drilling site (pl. I, grid J-7). View is to the northeast. |

Mansfield Channel — Mansfield Channel (fig. 13), located at the southern end of the National Seashore (pl. I), is 300 feet wide and 14 feet deep; it cuts through the island and lagoon to Port Mansfield on the Texas mainland. Mansfield Channel was dredged in 1957 by the Willacy County Navigation District and is maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The channel is used primarily by shrimp boats and pleasure boats.

|

| Figure 13. Mansfield Channel (pl. I, grid C-21). This channel, dredged through the island and lagoon in 1957, is used heavily by shrimp boats. The two jetties, constructed of large granite blocks, keep the channel mouth from being filled with sand transported by long shore currents, which generally move from south to north (right to left) here. View is to the east. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/tx/1980-17/intro.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2007