|

Texas Bureau of Economic Geology

Padre Island National Seashore: A Guide to the Geology, Natural Environments, and History of a Texas Barrier Island |

HISTORY OF HUMAN ACTIVITY ON PADRE ISLAND

Most of Padre Island has remained in its primitive state since humans first set foot on it. The natural resources of Padre Island and Laguna Madre have been used in simple ways by the three main groups who have visited and inhabited the island — Indians, Spaniards, and Americans. Small tribes of nomadic Indians hunted on the island and fished in Laguna Madre. Both Spaniards and Americans recognized the value of Padre as rangeland and took advantage of it. Now, with the establishment of Padre Island National Seashore and the preservation of a large part of Padre's environments, most of the island will be maintained in its primitive character.

Following is a brief account of the history of the Indians Spaniards, and Americans on Padre Island and their interaction with the natural environments. Most of this history is derived from an unpublished Bureau of Economic Geology manuscript written by Walter Keene Ferguson. Mr. Ferguson's primary source of information was the Padre Island National Seashore Historic Resource Study conducted by J. W. Sheire for the National Park Service (1971). The Historic Resource Study and other sources of historical information are listed under Historical References on page 84.

KARANKAWA INDIANS

The semiarid lands of the South Texas coastal bend, between the Guadalupe River and the Río Grande, were never inhabited by the Plains Indians, such as the Comanches and the Lipan Apaches. Instead, small tribes of Indians maintained a subsistence off the coastal lands by hunting and gathering food. One of the groups dwelling within this area was the Karankawas. The exact origin of the Karankawas is uncertain because little is known about their language and culture.

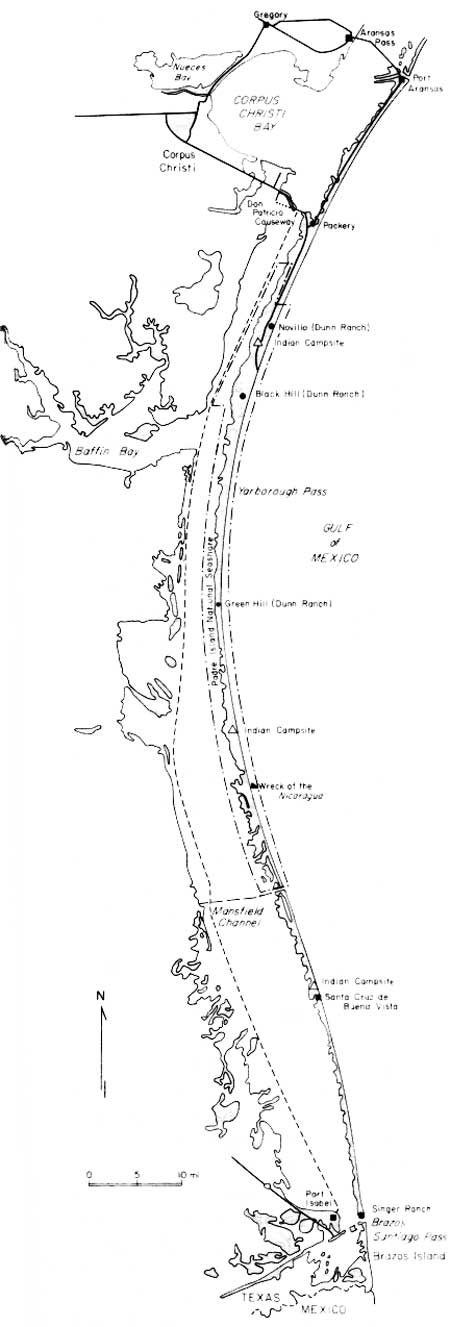

After sifting the tons of oystershells that formed the bulk of the "kitchen" middens, or trash heaps, left by the Karankawas, archeologists have been able to piece together some of the basic aspects of Karankawan culture. T. N. Campbell, author of An Appraisal of the Archeological Resources of Padre Island, Texas (1964), reports that there are 20 different Karankawa campsites in the northern 20 miles of Padre alone. The location of one of these northern campsites, as well as of two others farther south, is shown in figure 109. The reports of explorers, traders, and missionaries provide other sources of information on this culture.

The Karankawas tattooed and painted their bodies and coated themselves with a vile-smelling animal-oil mixture that repelled mosquitoes and Europeans alike. They were excellent fishermen and good hunters, using large cedar bows too strong for the average person to bend. Canoes, or pirogues, were made from hollowed-out logs. The food of the Karankawas varied with the seasons. Although they hunted deer and other large game and gathered nuts, berries, and cactus fruit, their diet consisted mostly of fish, shellfish, birds, and bird eggs obtained from Laguna Madre and vicinity.

The total population of the five Karankawa tribes is unknown, but estimates range from about 1,000 to as many as 28,800 (the larger estimate by W. W. Newcomb, Jr., personal communication, 1979). Separated into groups of 30 to 40, the Karankawas lived a nomadic life. They set up summer camps on Padre and wintered in crude, portable huts on the mainland. The tentlike lodges made of willow poles and deer skins would accommodate two families, or about seven or eight people.

Archeologists have gathered little evidence of Karankawan religion. The Indians apparently worshiped two deities called Pichini and Mel and held ceremonies for giving thanks and for imploring the assistance of these gods. The Karankawas evidently practiced cannibalism, but not to provide a food source. Cannibalism instead involved the superstitious belief that by eating the flesh of an enemy, the Karankawas could transfer the victim's strength to themselves.

As explorers and settlers invaded their country, the Karankawas resisted fiercely. Disease, lack of organization, and the Indians' small numbers, however, doomed them to extinction once others desired their land. The Karankawas became impediments to the expansion of Anglo-American and Mexican settlements.

The final fate of the Karankawas is uncertain. In the mid-1840's remnants of the once sizable Indian tribe reportedly fled southward. One group settled on south Padre Island and another group settled in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Conflicting reports exist about those who settled on Padre Island. A sensational account in 1846, by Samuel Reid of the Texas Rangers, maintained that some of the warriors, driven to desperation by their sufferings, murdered their women and children and chose Padre Island as a suitable place to linger out the remnant of their miserable lives (Sheire, 1971). Another final Karankawan account was in 1858. Problems in Tamaulipas forced a number of Karankawas to flee back across the Río Grande into Texas where they were "exterminated" by ranchers (Gatschet, 1891). In his book, The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times, W. W. Newcomb) Jr., (1961) commented on the Karankawas' endurance:

The Karankawas of the Texas Gulf coast are gone, yet they will forever stir our imaginations. Perhaps this is because, unlike ourselves, they faced daily and directly the stark realities of remaining alive. To those who have seldom been too cold, hot, or wet, never really hungry, and confidently expect to see many tomorrows, a people who had none of these advantages come as something of a shock. Our civilization is like a great blanket cushioning and protecting us from the raw world; the Karankawa blanket was thin and patchy. Yet, they survived, even thrived, and were happy with their ways. To Europeans and Texans it was astonishing and insufferable that such a people should prefer their own gods, food, and customs to civilization's blessings. But they did, and they clung to these ancestral ways. And for this they perished. To persevere to such ultimate tragedy is a highway to continuing remembrance.1

1Excerpt from The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times by W. W. Newcomb, Jr. copyright © 1961 by University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

SPANIARDS

Exploration

Invention of the printing press and the mariner's compass marked the beginning of the end for American Indians, for these inventions made possible the boom of European exploration and expansion in the 1500's. Exploration of the Padre Island region began in 1519, when Spanish Jamaican Governor Francisco Garay, eager to match the golden successes of Hernando Corteacute;s in Mexico, ordered Alonso de Piñeda to explore the north and west coasts of the Gulf of Mexico. Piñeda's main objective was to find the Strait of Anian — the rumored water passage to India. He did not find the nonexistent strait, but he did chart the Gulf coastline from the tip of Florida to Tampico. In the process he discovered and named the Bay of Corpus Christi and Isla Blanca (Padre Island) and touched ashore at the mouth of the Río de las Palmas — the Río Grande.

The Shipwrecks of 1554

In April 1554, a group of Spaniards landed on Padre Island, but certainly not by choice (Arnold and Weddle, 1978). Four ships had set sail from Veracruz carrying treasures and some of Mexico's wealthiest residents back to Spain. As the fleet reached Texas latitudes, it was struck by a fierce storm. The Spanish vessels were scattered by the raging storm. Three of the ships ran aground on Padre Island, but one made it safely to Havana. The survivors, exhausted and starving, took some supplies from the wreck and spent 6 days on Padre's beaches before they were greeted by a band of Indians. The Spaniards, fleeing southward under showers of arrows, were gradually reduced in number. Only a few Spaniards survived the ordeal, eventually making their way southward to a Mexican settlement and safety.

One shrewd nobleman who survived the shipwrecks, Francisco Vásquez, had left the group early and returned to the wrecks, where there remained a plentiful supply of food and other goods. Vásquez reasoned that ships would be sent to search for survivors and, particularly, the lost treasure. Within 3 months, Vásquez was rescued from Padre Island.

Colonization

When Piñeda had reported to Governor Garay on the 1519 expedition, he suggested that the region of the Río de las Palmas be colonized. Two subsequent colonization attempts failed, however, and these failures marked the area as unfit for habitation. But when Robert LaSalle established a French stockade, Fort Louis, on Matagorda Bay in 1685, Spanish interest in the South Texas region was rekindled. Alonso de León led five expeditions into the coastal region before he found LaSalle's abandoned fort in 1689. On one of these journeys he explored Baffin Bay (fig. 109).

|

| Figure 109. Historical sites on Padre Island. |

In a half-hearted effort to forestall any more French designs on this region, the Spanish authorities in Mexico ordered a presidio, or fort — La Bahía — built near the confluence of the San Antonio and Guadalupe Rivers at what is now Goliad. The Spaniards also established a mission, called Nuestra Señora Espíritu Santo de Zuñiga, to pacify the coastal Indians, especially the Karankawas. The mission, however, was finally abandoned as a failure. The Karankawas refused to give up their traditional life patterns, and the Spanish could not provide them security against the Comanches and Apaches.

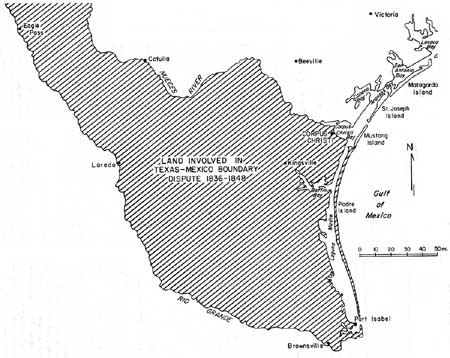

This same concern with the defense of the Texas region, which the Spaniards considered an invaluable buffer between Mexico and the expanding British and French colonial empires in North America, prompted the Spanish authorities to order José Escandón to explore the region and initiate civilian settlements in the late 1740's. Escandón launched a carefully planned and successful colonization program, which led to the establishment of settlements on both sides of the Río Grande from its mouth northwest to the site of Laredo (fig. 110). These settlers were the first to use this region for cattle grazing.

After the English defeat of the French at the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, the English gained all French and Spanish territory east of the Mississippi. Soon rumors spread that they were establishing forts along the Gulf in an effort to expand their empire. Escandón was ordered to investigate these rumors, and one of the expeditions that he sent under the direction of Diego Ortiz Parrilla was to explore Isla Blanca — now Padre Island. Parrilla's report contains probably the first description of Padre Island.

Padre Ballí

By 1760, Spanish cattle grazed on land from what is now Mexico north to the Nueces River (fig. 110). This region was no longer a wilderness but a territory of large ranches. One story tells of a hurricane flood in 1791 that inundated Padre Island and the mainland shore, killing 50,000 head of cattle belonging to one Spanish cattle baron. But an extensive ranching enterprise was not begun on Padre Island until 1800, when the Portuguese priest, Padre Nicolas Ballí, a member of a land- and cattle-rich family settled near the Río Grande, finally succeeded in gaining a grant to the island from King Charles IV of Spain. Padre Ballí established ranching operations on the island and was joined in the venture by his nephew, Juan José Ballí, although neither of them actually lived on Padre Island. The ranch headquarters, Santa Cruz de Buena Vista, was located about 26 miles from the southern end of the island (fig. 109).

|

| Figure 110. South Texas. Between 1836 and 1848, Texas and Mexico both claimed the land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

When Padre Hidalgo launched the successful struggle for Mexican Independence in 1810, Padre Ballí fled to Santa Cruz, as he was known to be sympathetic to the Spanish establishment, which had granted him and his family land. After the revolution, Ballí had to work long and hard to get the Mexican government to reconfirm his title to "Padre's Island." Unfortunately, Padre Ballí died in the same year that the grant was verified — 1828. The Ballí family continued to ranch on the island until 1840, but they had begun to sell parts of their land as early as 1830.

AMERICANS

Smuggler Kinney

As the Mexican ranchers were developing the grazing potential of South Texas, the first Anglo-American settlers were colonizing the fertile lands along the Brazos and Colorado Rivers in central Texas. When the Texas Revolution broke out in 1836, the sparsely settled ranching country to the south became a no-man's-land. In the midst of this confusion, notorious smuggler Henry Lawrence Kinney established trading operations in the Corpus Christi Bay area. By 1840, he had established a trading post on the south rim of the bay and had a personal police force of 40 men.

A Boundary Dispute and the Mexican War

A dispute over the border between the new Republic of Texas and Mexico intensified when the United States voted to annex Texas in 1845. The American government chose to support Texas' claim of the Río Grande as its southern boundary rather than the Nueces River farther north, as held by the Mexican government (fig. 110). In a show of power, President Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed area between the two rivers, a region including Padre Island. Taylor and his troops traveled by sea to Rockport and, after a 6-month stay at Kinney's trading post, moved on to Port Isabel to establish the main supply base. Fort Brown was established at this time. Captain Ben McCulloch and his Texas Rangers first brought the American flag to Padre Island as they traveled its length to report for duty with Taylor's forces. And, on Taylor's orders, Lieutenant George Gordon Meade, later to gain fame as the commander of Union forces at Gettysburg, conducted a 10-day survey of the navigability of the waters of Laguna Madre and transportation routes on the island itself. Meade's map, made in November 1845, was the first detailed map of the island. At the end of the war with Mexico in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the Río Grande as the boundary between Texas and Mexico, and finally, Padre Island became a part of the United States.

Port Isabel (fig. 110) was the vital link in the American supply system during the Mexican War. Brownsville and Corpus Christi also experienced a wartime boom, and during the gold rush years in the mid-1800's, they became important as supply stations for the forty-niners' trek across the arid Southwest. Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy, later of King Ranch fame, made a small fortune off their 200-ton, shallow draft sternwheeler steamboats that plowed up the Río Grande, almost as far as Laredo (fig. 110).

John Singer and His Buried Treasure

The booming Port Isabel trade had attracted the attention of John Singer, whose brother Isaac was starting his sewing machine empire. In 1847, the adventurous Singer and his wife and son set out for Port Isabel to establish a shipping business. They were swept off course by a storm, however, and their schooner was dashed aground on southern Padre Island. The Singers took a liking to their new home and set up housekeeping on the southern tip of the island (fig. 109).

The last of the Ballí descendants had left the island in 1844 in the face of the American annexation of Texas with its Río Grande border. After the Mexican War, land-hungry Texans turned their attention to the Mexican ranching lands south of the Nueces. They posed such a threat to the Mexican landowners that most of the Mexicans felt compelled to sell out at any price in order to salvage anything. By such purchases, payment of back taxes, or simply squatter's rights, Americans had acquired most of these lands by the outbreak of the Civil War. As of 1846, José María Tovar owned the northern half of Padre, and the southern half was owned by Ballí's seven heirs. But by the mid-1850's, almost all of the original Ballí grant was in American hands. The Singers purchased one seventh of the south half from one of the Ballí heirs in 1851 and by 1855 had leased much of the rest of the southern part for their thriving ranching business.

Six Singer children were born on the island, and at the height of the ranching boom, the Singer headquarters consisted of about l5 buildings. The Singers' profitable ranching business was shortlived, however. Because of the Singers' Union sympathies, the Texas Confederates ordered them off the island in 1861. Singer was forced to make a hasty departure and quickly buried $80,000 in a jar near his home. This was the basis of one of the island's most intriguing treasure stories, for after the Civil War, Singer was unable to find the cache. A short time later Mrs. Singer died, and the Singer family permanently left the island in 1866, selling their holdings to railroad entrepreneur Jay Cooke.

The Civil War

During the Civil War, the effective Union blockade cut off all direct Confederate trade with Europe. The Confederates, however, quickly found a solution to the blockade. They transported cotton overland to Mexico south of Brazos Santiago Pass at the southern tip of Padre (fig. 109). From there it was shipped out on European vessels and traded in Europe for drugs, food, clothing, and war supplies. The Mexican port of Bagdad became a boom town full of deserters, spies, and gamblers. In an effort to cut the flow of Confederate goods to Bagdad, 7,000 Union soldiers stormed ashore on Brazos Island south of Padre in November 1863. They captured Brownsville, which forced the cotton caravans to enter Mexico as far north as Eagle Pass (fig. 110).

The King Ranch

During the confusion of the Civil War, the unattended cattle herds in South Texas expanded tremendously. Throughout the 1850's, Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy had been acquiring the lands that would constitute the legendary King Ranch, which now covers almost 1 million acres. As early as 1854, King purchased 12,000 acres on Padre Island from a niece of Padre Ballí. And in the early 1870's King and Kenedy leased additional acreage on the island. At the height of their operations on the island, there were some 70 people located at the headquarters near the site of Ballí's old headquarters, Santa Cruz (fig. 109). King's ranching operations on the island, however, were severely curtailed after a damaging storm in 1880.

The Meat Packeries

One sidelight to the history of ranching on Padre was the appearance of meat packeries along the coast and on the island during the 1870's. The tremendous oversupply of cattle in relation to the Texas market had dropped beef to a few cents per pound. The cattle hides became more valuable than the meat. At these packeries, cattle were slaughtered for their hide and tallow, and some beef was packed in salt to be shipped. During 1872, 300,000 hides were shipped out of Rockport and Corpus Christi alone. One large packery (fig. 109) was located just south of Corpus Christi Pass on Packery Channel. By the end of the 1870's the packery boom was over as the cattle drives to railheads in Kansas and Nebraska poured Texas beef into midwestern and eastern markets.

Patrick Dunn — The "Duke" of Padre

The profitable days of the open range came to an end at about the same time as the packeries did. In 1882, Kenedy fenced in his La Parra ranch; this marked the beginning of the end of the open range. This prompted the appearance of the real successor to the Padre Island ranching heritage of Ballí and Singer — Patrick Dunn. Dunn was the son of Irish immigrants who came to Corpus Christi in the 1850's. He became a successful rancher by taking advantage of the free open range. Then the advent of barbed wire fencing directed his attention to the natural "fences" of Padre, bounded by the Gulf on one side and the lagoon on the other. He first leased land on the northern part of the island in 1879. By 1926, he owned almost all of Padre's 130,000 acres. During the periodic roundups, Dunn's cowboys, or vaqueros, started at the south tip of the island and drove the cattle from line camp to line camp, holding them in corrals at night. The line camps were built l5 miles apart, the distance the cattle could be driven in 1 day and corralled before dark. The remains of Novillo, Black Hill, and Green Hill camps are visible today (fig. 109, also fig. 83). The cattle were then driven to market across the lagoon at a point below Flour Bluff.

Dunn — the "Duke" of Padre — became a legend in his own time. He closely supervised his extensive ranching operations and conducted experiments with non-native grasses. A notable in the Democratic party, he was a State legislator from 1910 to 1916 and helped launch John Nance Garner into politics. In 1926, Dunn sold his surface rights to real estate developer Colonel Sam Robertson. The Duke retained grazing and mineral rights and ranched until his death in 1937. His son, Burton Dunn of Corpus Christi, continued to run the Dunn ranching business. The Dunn line camps were still used as collecting points for cattle during roundups until 1971, when grazing was terminated within the Padre Island National Seashore.

The Wreck of the Nicaragua

Protruding above the waters of the surf about 10 miles north of Mansfield Channel are parts of the rusted boilers and 180-foot frame of an old steamship (fig. 109 and pl. I, grid M-20). The Nicaragua went aground on Padre in 1912. The purpose of the boat's trip, its cargo, and the cause of the wreck remain mysteries. One popular theory is that the Nicaragua was carrying guns and ammunition to Mexico to be used in an overthrow of the Mexican government. The boat supposedly ran aground after it was sabotaged by Mexican spies who had slipped on board. Another story, however, is that the Nicaragua was merely a banana boat.

Colonel Sam's Dreams of an Island Resort

Colonel Sam Robertson, a former scout for General Jack Pershing, was the first representative of the age of the automobile and tourism to foresee the resort potential of Padre. After purchasing Dunn's Padre holdings for $125,000, Robertson began work on a wooden causeway from Corpus Christi to Padre. This Don Patricio Causeway (named after Patrick Dunn) opened on July 4, 1927. It consisted of two wooden troughs just wide enough to fit the wheels of a Model T Ford. The causeway was destroyed by a hurricane in 1933, but the supports are still visible across Laguna Madre (fig. 109). Colonel Sam also provided ferry service to both ends of the island and access to his Twenty-Five Mile Hotel on the southern end of the island.

Robertson's big hopes for a tourist boom fizzled, and then the Depression hit in 1929. No longer able to keep up his payments, Colonel Sam sold his island property to Albert and Frank Jones, two brothers from Kansas City. The Jones brothers established the Ocean Beach Drive Corporation but did not expand Robertson's developments. The hurricane of 1933 that destroyed the Don Patricio Causeway also destroyed most of Colonel Sam's buildings, wiping out any ideas the Jones brothers may have had of continuing with Robertson's schemes.

Movement Toward an Island Park

During the 1920's, Governor Pat Neff established the foundations for Texas' State park system, and during the 1930's Federal funds made the parks more usable and accessible to the public. It was at this time that the drive began to establish a State park on Padre Island. In 1937, Representative W. E. Pope of Corpus Christi introduced a bill authorizing the State Parks Board to acquire acreage for a park on the island. The promoters of this bill established the Padre Island Park Association, which rallied support from all over South Texas. The Legislature passed the bill, but Governor James Allred vetoed it. The basis of his veto was that the State might already own most of Padre because the island was much larger than the 1-1/2 leagues included in Ballí's original grant. In 1945, however, the Texas Supreme Court upheld the private ownership of all of the island.

Obviously, Allred's veto, along with the drawn-out title suit and World War II, slowed the movement for establishment of a park. Meanwhile, Robertson's successors were hard at work. A causeway from Corpus to the island was completed in 1950, and the construction of a causeway and bridge from Port Isabel to Padre followed 4 years later. This obviously stimulated resort development. John L. Thompkins led this drive with plans for a multi-million-dollar development, Padre Beach. And today, both the northern and southern ends of Padre are lined with resort motels and condominiums.

While this development was beginning, the National Park Service in 1954 undertook a comprehensive survey of America's 3,700 miles of coastline. The survey noted that only 6.5 percent of the coastline was reserved for public recreation. It was recommended that three coastal areas be included within the National Park domain: (1) Point Reyes, California, (2) Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and (3) Padre Island, Texas. Senator Ralph Yarborough introduced the first Padre Island National Seashore bill in 1958, and the National Seashore became a reality in September 1962.

SUMMARY OF NATURAL RESOURCE USE

Use of the natural land, water, and mineral resources of Padre Island and Laguna Madre has changed over the several hundred years that people have inhabited the area. Primitive use by the Karankawa Indians changed to the more ordered Spanish and American ranching operations and then to still more sophisticated uses such as petroleum exploration and production and resort development. The Karankawas relied heavily on the island and lagoon for their food sources, but their needs were simple, and their use of the land and water environments was minimal. Setting up temporary camps on Padre in the summers, the Indians hunted birds and other game on the island and fished in Laguna Madre. Around 1805, the Spaniards brought cattle to graze on Padre's grass-covered barrier flats. Americans later continued the ranching operations. Cattle raising was the primary use of the island until 1971, when the last cattle were removed from the area of the National Seashore.

Other recent uses of the resources of Padre Island and Laguna Madre include oil and gas exploration, resort development, recreation, commercial fishing, and shipping along the Intracoastal Waterway. Entrepreneurs began planning resort developments for Padre as early as the 1920's. Although the middle part of the island is now preserved as the National Seashore, resort communities cover both ends of the island. Petroleum production began in the Seashore area in the late 1930's. The first discovery was in Laguna Madre, west of South Bird Island. Exploration and production continue on the island, in the lagoon, and offshore in the Gulf of Mexico.

Man's use of island and lagoon resources has had some adverse effects on the environments. Overgrazing of the vegetated barrier flats and dunes of Padre, coupled with droughts, at one time destroyed much of the plant cover on the island. This left large barren areas covered with loose dune sand that was free to migrate. Much of the loose sand blew into and filled certain parts of Laguna Madre (Price and Gunter, 1943), especially in the Land-Cut Area and just north of the mouth of Baffin Bay (pl. I, grids J-2 and K-2). Thus, the overgrazing may have indirectly had a lasting impact on the lagoon, but Padre's environments seem to be recovering well from devegetation caused either by natural processes or by man.

Other adverse alterations of lagoon environments have been those produced by the deposition of dredged spoil. The spoil not only blots out the habitats of numerous fish, invertebrates, and marine plants but also alters the circulation patterns of lagoonal waters. The location and manner of deposition of spoil are carefully studied by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers before dredging so that disturbance of lagoon environments will be minimal.

Activities of the petroleum companies are carefully planned so that the natural environments are not greatly affected. Very little disturbance of the environments is visible either at drilling and production sites or along buried pipelines laid to transport gas from producing wells. Large-wheeled vehicles used by seismic crews have destroyed little vegetation.

In spite of changes in natural resource utilization and certain effects of human interaction with the environments, most of Padre has remained in a primitive state. Establishment of the National Seashore in 1962 now limits the use of much of this wilderness to recreation and ensures that a large part of the island will remain undeveloped. Those who visit the National Seashore can help protect the natural environments by preventing the careless destruction of vegetation, especially along the fore-island dune ridge, which serves as a barricade to storm winds, waves, and tides.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/tx/1980-17/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2007