|

Texas Bureau of Economic Geology

Down to Earth at Tuff Canyon, Big Bend National Park, Texas |

HOWDY FROM TUFF CANYON IN BIG BEND!

Just visiting? Hope the visit is fun AND educational. This guidebook ought to help with both. It will lead you down some exciting paths in some beautiful scenery, at the same time helping you understand how that scenery came to have the shape it has today. It will also tell you how scientists use the clues they have found in the rocks to tell the history of the canyon and its surroundings. Some of the explanations might get a tad technical, so whenever you see a word in boldface, look it up in the glossary in the back. Oh, and because topographic maps of the Big Bend area show elevations above sea level in feet, and because odometers in U.S. motor vehicles still register in miles, in this guidebook contour lines are labelled in feet and road distances in miles. In fact, taking a cue from the first book in this series, Down to Earth at McKinney Falls State Park, Texas, by Jay A. Raney, I have set down ALL measurements according to the English system.

Of course part of the scenery is the incredible flora and fauna of the area. Depending on the time of year (and day!) you might be visiting, you may happen to run across any number of critters, birds, and plants. Coyotes, collared peccaries (javelinas, wild pigs), jackrabbits, skunks, and snakes all hunt at night, but the coachwhip snake, kangaroo rat, and earless lizard might be encountered during the day. More than 434 species of birds have been identified within Big Bend, for the park lies right on the flyway for birds winging north out of Mexico. Tuff Canyon's bird life is limited, however, to only a handful of species. These include residents of the nearby desert that may visit the canyon in search of food, shelter, or water; those that might be considered transients only; at least one neotropical migrant that nests on the canyon walls some years. This latter species is the cliff swallow, which takes advantage of the canyon walls for a place to build its nest of mudballs. During years of adequate rain, cliff swallows take mud from wet areas, roll the mud into tiny balls, and construct a narrow-mouthed nest on the canyon walls (see photo). Another nesting bird of the canyon is the rock wren, a year-round resident. It utilizes crevices in the walls or other flat surfaces. Rock wren males build tiny ridges, in which they add rocks, bones, and other tiny objects, in front of their nest sites, just to impress the female rock wrens! Other feathered desert creatures that are apt to visit Tuff Canyon at one time or another include the black-throated sparrow, black-tailed gnatcatcher, Pyrrhuloxia, cactus wren, canyon towhee, and common raven. Any number of transients could visit the area as well, even some of the neotropical migrants such as vireos, warblers, tanagers, grosbeaks, and sparrows. These northbound and southbound migrants are constantly in need of food and water, and Tuff Canyon, because of its shade and potential for holding water for a longer period than the open desert, is always worth checking. (For further reading on the birds of Big Bend, see Heralds of Spring in Texas by Roland Wauer or any of four other of Wauer's books on birds, all available at park headquarters.)

The kangaroo rat and the roadrunner exemplify adaptations to the arid climate of Big Bend because neither drinks water. They rely instead on their diets and specialized digestive systems for survival. Many critters get along in the desert by coming out only at night, however. Most snakes do so because summer temperatures during the day in the desert would kill them within minutes. Some Big Bend lizards, though, brave that heat to hunt during the day. Most often you'll see the western whiptail. The greenish lizard may be seen running on its hind legs like a miniature out of Jurassic Park. Lizards are about the biggest ground critters you scare up on a noonday walk, unless you run across a lizard eater, such as the big pink western coachwhip snake. Critters of the smaller variety include tarantulas, scorpions, and millipedes, but they're rare.

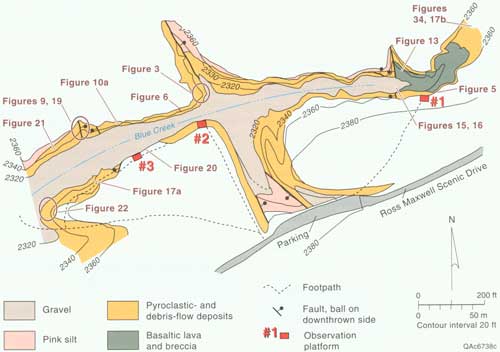

Many species of cactus grow in Big Bend, as well as candelilla, ocotillo, creosote, Chisos agaves, mesquite (see fig. 21, a little farther on in the book) and a number of yuccas, most noticeably the dagger yucca. Wildflowers such as Texas bluebonnets, narrow-leaf globe mallow, and prickly poppy bloom into late spring. (For a more in-depth discussion of flora of Big Bend, see Ross Maxwell's The Big Bend of the Rio Grande, available at the park headquarters.)

Please enjoy our National Park, but also please remember that disturbing or removing rocks, plants, animals, or artifacts is prohibited within National Park boundaries. To get permission to conduct scientific research, including sampling, you must write a research proposal and submit it to the Superintendent, Big Bend National Park, National Park Service, Big Bend National Park Texas 79834-0129.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/tx/2000-DE02/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 03-Aug-2009