|

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

People of the Upper Gila River

More questions than answers surround the story of people who built structures in natural caves of Cliff Dweller Canyon. Archeological evidence suggests that many different groups of people have inhabited this area over thousands of years. What motivated one group to build inside the caves between the late 1270s and 1300? And why was their stay so short?

The Mogollon

The people who built the cliff dwellings were part of the Mogollon (mo-go-yon) culture. They combined hunting and gathering with farming and traditionally built pit houses or surface pueblos in the mountainous areas of Arizona and New Mexico. The Mogollon found abundant game and fertile soil in the Gila River valley for both native vegetation and their crops of corn, beans, and squash. Breaking with tradition, the Tularosa Mogollon built inside the caves of Cliff Dweller Canyon with rock, mortar, and timbers from trees cut between 1276 and 1287. But by 1300 the Gila Cliff Dwellers had moved on.

A unique style of black-on-white pottery bowl from the Mimbres branch of the Mogollon culture was common to this area during the classic Mimbres phase (1100 to 1150). The designs and details of most pottery found in the cliff dwellings are unique to the Tularosa phase (1100 to 1300). With the pottery as just one clue, archeologists believe the Gila Cliff Dwellers came here from near the Tularosa River, 60 miles north of the national monument.

The Mogollon were not the only group to have lived in this area. As mobile hunter-gatherers following herds of game through the Gila River valley, the Apaches left behind artifacts like bows and arrows fashioned from materials abundant in this area.

Approximately 40 rooms were built inside several natural caves in Cliff Dweller Canyon. Artifacts and architectural elements show that these ancient cultures traded not only materials but ideas. The Gila Cliff Dwellers left behind macaw feathers from Central America, and they built T-shaped doorways also used by other cultural groups.

With cultivated crops like corn came a more sedentary life. Perhaps in time the area's natural resources, already affected by drought, no longer sustained the Mogollon.

The Chiricahua Apache

After the Mogollon left, no one appears to have lived in this area for over 100 years. Apaches migrated to the upper Gila River about 1500, although some of their oral traditions claim it has always been their homeland. Legendary leader Geronimo was born near the Gila River headwaters in the early 1820s as Mexico challenged Apache control of the area. Thirty years later, with the area under U.S. control, army posts were built to protect new Anglo settlers as area mining towns grew and ranching was established throughout the Gila River valley.

By 1870 the federal government began relocating the Apaches onto reservations. But not until September 1886 were the last Be-don-ko-he—as Geronimo's people were known—led by Geronimo himself, ultimately forced from their ancestral lands.

Exploring the Cliff Dwellings and Wilderness

From Early Settlement to the Gila Wilderness

Led by Juan de Oñate, Spanish colonists settled east and south of this area in 1598. The Spanish stayed close to main travel routes and the Rio Grande valley and by the early 1800s had not penetrated the Gila River country as far as these cliff dwellings.

After an 1878 prospecting trip, miner H.B. Ailman documented the cliff dwellings. When archeologist Adolph Bandelier came here in 1884, the cliff dwellings had been looted by earlier visitors. They took many artifacts and obliterated much of the archeological record. In 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed the national monument to prevent further damage and vandalism.

Settlement of this region by miners and ranchers accelerated after the Apache Wars ended in 1886. Boom towns for mining, like Pinos Altos and Mogollon, cropped up. Ranchers homesteaded the land for raising cattle and sheep. Forests of the highcountry began to be cut for timber.

Across the United States wild lands were disappearing fast. Many people wondered how our wilderness heritage could be preserved. The pioneering ecologist Aldo Leopold was assistant district forester for the Southwest national forests early in his career. He persuaded his agency to establish the Gila Wilderness in 1924, the nation's first designated wilderness area. Now the Gila Wilderness protects the upper Gila River watershed. This is the longest undammed stretch of river in the contiguous 48 states. Leopold's vision helped inspire the 1964 Wilderness Act that now preserves the wilderness of over 109 million acres of federal public lands.

Planning Your Visit

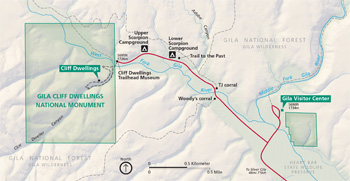

(click for larger maps) |

Gila cliff Dwellings National Monument lies 44 miles north of Sliver City on NM 15. Allow two hours driving. No public transportation serves this area. Stop first at the multi-agency Gila Visitor Center for information, exhibits, a short film, and bookstore. Staff will answer questions and help plan your visit. Parking for the cliff dwellings is at the trailhead, a two-mile drive from the visitor center. Service animals are welcome.

Cliff Dwellings Trail The one-mile loop trail to and through the cliff dwellings climbs 180 feet above the canyon floor. Allow one hour round-trip. Views of the cliff dwellings are possible after a ¼-mile hike in the canyon bottom. The trail that continues to the dwellings is steep and rocky in places. Wear sturdy shoes, pace yourself (use the benches), and take water. Find information about guided tours and programs at the trailhead, visitor center, or Monument website. The short Trail to the Past from Lower Scorpion Campground leads to a small dwelling and a pictograph panel.

Safety and Regulations All plants, animals, artifacts, and structures are protected by federal law. Please enjoy the natural and cultural resources while staying on the trail at all times. For the safety of others, do not throw or roll rocks into the canyon. Watch children closely. Food, tobacco products, pets, and drinks other than water are not permitted on the trail. Free kennels are available at the contact station. For firearms regulations check the park website or ask a ranger.

Hours and Fees The Monument and the Gila Visitor Center are open daily. Contact the Monument or check its website for hours of operation of the visitor renter and the cliff dwellings trail. Note: New Mexico is in the Mountain time Zone and observes daylight saving lime, while Arizona does not observe daylight saving time.

Fees Fees are collected (exact change required) at the trailhead's self-pay station. Contact the Monument for admission fee information. The federal park passes are accepted at the trailhead and sold at the visitor center.

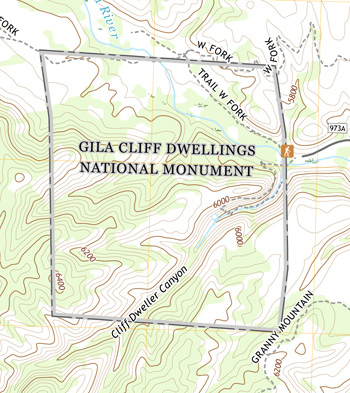

Area Information The 513-acre national monument is surrounded by the 558,000 acre Gila Wilderness, part of 3.3 million acres of public forest and range land within the Gila National Forest. Campgrounds and picnic areas are available on national forest lands throughout the valley. Lodging, an RV campground, and basic food items are available in Gila Hot Springs, four miles from the Monument.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument — November 16, 1907 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Archeological Survey: Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 47 (James E. Bradford, 1992)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Administrative History: Gila Cliff Dwellings (HTML edition) Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 48 (Peter Russell, 1992)

Evaluating sources of hydrochemical variability and mixing in the upper Gila river, New Mexico (©Pavel Vakhlamov, Master's Thesis University of New Mexico, December 2019)

Fire Management Plan Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect (March 2003)

Foundation Document, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico (June 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico (January 2016)

Geologic Map of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (2014)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2014/849 (K. KellerLynn, August 2014)

Geology and Petrogenesis of Ash-Flow Tuffs and Rhyolitic Lavas Associated with the Gila Cliff Dwellings Basin-Bursum Calder Complex, Southwestern New Mexico (©Sheila June Seaman, PhD Thesis University of New Mexico, May 1988)

Hydrogeology and Water Supply Wells at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (Larry Martin, February 4, 2005)

Junior Ranger, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (2008; for reference purposes only)

National Monuments of New Mexico: IV—Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 5 No. 15, November 2, 1918)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (Diane Traylor and Charles L. Scheick, April 8, 1986)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2019/1961 (Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers, Andy Hubbard, Anna Mateljak, Deborah Angell and Mark Brunson, August 2019)

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Report on Wind Cave National Park, Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin, Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1913 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Senior Ranger, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (2008; for reference purposes only)

Soil Inventory Results and Relationships to Vegetation Monitoring Data at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2011/479 (Travis Nauman, August 2011)

Some New Mexico Ruins (Edith Latta Watson, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 23 Nos. 7-8 , August 27, 1927)

Springs, Seeps and Tinajas Monitoring Protocol: Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert Networks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1796 (Cheryl McIntyre, Kirsten Gallo, Evan Gwilliam, J. Andrew Hubbard, Julie Christian, Kristen Bonebrake, Greg Goodrum, Megan Podolinsky, Laura Palacios, Benjamin Cooper and Mark Isley, November 2018)

Status of Climate and Water Resources at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument: Water Year 2016 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1615 (Evan Gwilliam, J. Andrew Hubbard, Laura Palacios and Kara Raymond, March 2018)

Terrestrial Vegetation and Soils Monitoring at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument: 2009 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2010/375 (J. Andrew Hubbard and Sarah E. Studd, September 2010)

The Archeology of Gila Cliff Dwellings Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 36 (Keith M. Anderson, Gloria J. Fenner, Don P. Morris, George A. Teague and Charmion McKusick, 1986)

The U.S. Cavalry at the Gila River Cliff Dwellings, 1885 (Col. G.H. Sands, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 64 Nos. 11-12, November/December 1957)

TJ Ruin: Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 21 (Peter J. McKenna and James E. Bradford, 1989)

Vegetation Inventory, Mapping, and Characterization Report, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2019/1946 (Sarah E. Studd and Jeff Galvin, June 2019)

gicl/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025