|

Golden Spike National Historical Park Utah |

|

NPS photo | |

Spanning a Continent

No sooner were America's first railroads operating in the 1830s than people of vision foresaw transcontinental travel by rail. The idea gained support as a national railroad system took shape. By the beginning of the Civil War, America's eastern states were linked by 31,000 miles of rail, more than in all of Europe. Virtually none of this network, however, served the area beyond the Missouri River. Until the Great American Desert and the Rockies were bridged, the vast western territories would be a part of the nation in name only. A continent-spanning railroad would also bring more tangible benefits: It would boost trade, shorten emigrants' journey, and help the army control American Indians opposed to white settlement. Anticipating great financial and political rewards, northern, midwestern, and southern senators made their cases for locating the eastern terminus in their regions.

In California, Theodore Judah had his own plan for a transcontinental railroad. By 1862 the young engineer had surveyed a route over the Sierra Nevada and persuaded wealthy Sacramento merchants to form the Central Pacific Railroad. That year Congress authorized the Central Pacific to build a railroad eastward from Sacramento and in the same act chartered the Union Pacific Railroad in New York. After the Civil War had removed the southern senators from the debate over the eastern terminus location, the central route near the Mormon Trail was chosen, with Omaha as the eastern terminus. Each railroad received loan subsidies of $16,000 to $48,000 per mile, depending on the difficulty of the terrain, and 10 land sections for each mile of track laid.

The Central Pacific broke ground in January 1863 and the Union Pacific that December, but neither made much headway while the country's attention was diverted by the Civil War. Investors could reap greater profits from the war, and the army had first priority on labor and materials. So Central Pacific's Collis Huntington and Union Pacific's Thomas Durant, exemplars of the no-holds-barred business ethics of the period, visited Washington with enough cash to help congressmen understand their problems. A second Railroad Act of 1864 doubled the land subsidies, but little track was laid until labor and supplies were freed at war's end.

Central Pacific crews faced the rugged Sierra range almost immediately. While the Union Pacific started on easier terrain, its work parties were raided by Sioux and Cheyenne. With eight flatcars of material needed for each mile of track, supplies were a logistical nightmare for both railroads, especially Central Pacific, which had to ship every rail, spike, and locomotive 15,000 miles around Cape Horn. Both pushed ahead faster than anyone had expected. The work teams, often headed by ex-army officers, were drilled until they could lay two to five miles of track a day on flat land.

Union Pacific drew on the vast pool of America's unemployed: Irish, German, and Italian immigrants. Civil War veterans from both sides, ex-slaves, and even American Indians—8,000 to 10,000 workers in all. It was a volatile mixture, and drunken bloodshed was common in the "Hell-on-wheels" towns thrown up near the base camps. Because California's labor pool had been drained by the rush for gold, followed by the silver boom. Central Pacific hired several thousand Chinese, the backbone of the railroad's work force.

By mid-1868 Central Pacific crews had crossed the Sierra and laid 200 miles of track, and the Union Pacific had laid 700 miles over the plains. As the two work forces neared each other in Utah, they raced to grade more miles and claim more land subsidies. Both pushed so far beyond their railheads that they passed each other, and for more than 200 miles competing graders advanced in opposite directions on parallel grades.

Congress finally declared the meeting place to be Promontory Summit, where, on May 10, 1869, two locomotives pulled up to the one-rail gap left in the track. After a golden spike was symbolically tapped, a final iron spike was driven to connect the railroads. The Central Pacific laid 690 miles of track; the Union Pacific 1,086. They had crossed 1,776 miles of desert, rivers, and mountains to bind together East and West.

A "Grand Anvil Chorus"

Surveying

Surveyors, working hundreds of miles ahead, set no grade steeper than

116 feet-of-rise per mile.

Grading

Using picks and shovels, carts, one-horse scrapers, and black powder,

graders prepared about 20 miles of bed at a time, cutting ledges,

blasting hills, and filling huge ravines.

Trestles and Tunnels

Workers five to 20 miles ahead of tracklaying gangs built high wooden

trestles and dug tunnels. The Central Pacific blasted 15 tunnels through

Sierra granite, sometimes resorting to dangerous nitroglycerine.

Track Laying

On 2,500 ties per mile, one gang could lay two pairs of 30-foot,

560-pound rails a minute. Spikers drove 10 spikes per rail, three blows

per spike. Railbenders formed curves with sledgehammers.

Telegraph

The nation's second transcontinental telegraph was strung beside the

track as the railroad advanced.

Snow Sheds

Drifts and avalanches so hindered trains in the Sierra Nevada that the

Central Pacific had to build 37 miles of peaked snow sheds and sloped

galleries to keep snow off the tracks.

End of the Frontier

Imagine watching the last spike driven to complete the transcontinental railroad. Not too long before it had seemed an impossibility. The vast distance to be spanned, equal to the breadth of Europe, overwhelmed the early 19th-century mind. When Dr. Hartwell Carver first proposed the idea in 1832, it was as audacious as would have been a prediction in 1932—before TV and computers—that we would all watch a human walk on the moon by 1969.

Exactly a century before that event, the railroad too, in the words of a contemporary reporter, overcame "that old enemy of mankind, space." The transformation of the western United States was wrought by two rails four feet eight and one-half inches apart, snaking across hundreds of miles of sparseness. They joined two oceans and cemented the political union of states with a physical link.

But they were also a wedge through the frontier. The West belonged to the American Indians and the enormous herds of buffalo on which they depended. Many Indians fought white settlement of their land, but as the railroads brought in car after car of troops and supplies, the warriors could no longer repel the army. Settlers flowed in behind and put the land to the plow, while millions of buffalo were killed.

For these late emigrants, the railroad changed what it meant to be a pioneer. A journey that had taken six months by ox-drawn wagon took six or seven days by train. The Union Pacific built railroad stations along the way, and settlements grew up around them. Some railways sold supplies and even provided dormitories for emigrants until they could settle. Twenty-one years after the railroad was completed, the frontier was history.

Even before it was completed, the railroad had begun to work its changes on the West. As the railheads moved across the land, supply houses and service businesses grew up in their wakes. Some tent towns like Reno and Cheyenne survived to become respectable cities. Workers who had been trained on the railroad built towns and staffed factories and mines.

A major anticipated benefit of the railroad—increased trade with the Far East—never materialized. The Suez Canal was completed the same year as the railroad, and Far East goods could now be shipped to Europe faster by way of the canal than across America. But that loss was compensated for by the rapidly growing western rail trade, out of which a vigorous, interlocking economy developed. The western mountains were rich with low-grade silver, lead, and copper ores, made profitable by long trains of ore cars. They were used by industries in the East, whose products found a growing market in the West. Western agriculture made great advances as new farming techniques, livestock strains, and machinery moved in by rail. Cash, generated by the produce shipped east, poured into the region, and budding western financiers learned how to raise money to capitalize new industry. Factories were built, and the growing industrial population provided a new market for western farm produce.

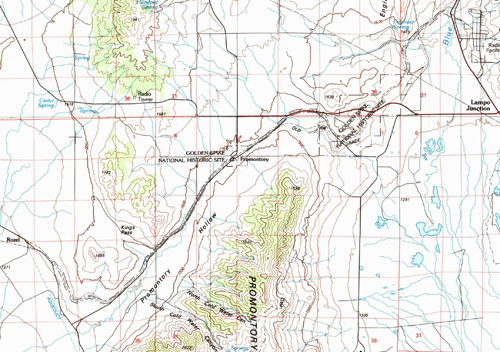

(click for larger maps) |

More than economically, the railroads tied the West to the eastern states. They altered the very pace of life, putting people on a schedule who had always geared their activities to natural rhythms. National politics came west, as candidates made whistle stop tours of small towns in search of votes. As railroads made travel into the West safe and comfortable, visitors from the eastern states and Europe toured the New America. Their sometimes exaggerated accounts of the region engendered the Old West myths that helped shape American culture. With the coming of the railroads, the West, for so long the vast, forbidding "out there," was brought into the national life.

Planning Your Visit

Golden Spike National Historic Site is 32 miles west of Brigham City. Southbound travelers on I-84: use exit 26 and drive south on Utah 83 to Golden Spike Drive. Turn right and follow signs to the visitor center (eight miles). Other interstate travelers: use exit 368 off I-15 and drive west on Utah 13 and 83 through Corinne to Golden Spike Drive. Turn left and follow signs to the visitor center. Motels, restaurants, and camping are available in Brigham City, Tremonton, or Ogden.

The visitor center has exhibits, information services, and audiovisual programs. About 1.7 miles of track have been relaid on the original roadbed where the rails were joined, and working replicas of the Jupiter and No. 119 operate during the summer season.

For a Safe Visit

Stand well back from steam locomotives during operation to avoid

scalding. Beware of hot and greasy parts. • Do not place coins or

other objects on rails. • Observe speed limits and drive carefully,

especially along the railroad grade. • All natural features and

cultural artifacts are protected by federal law. • Metal detectors,

digging, and fires are prohibited.

Source: NPS Brochure (2005)

Documents

A Footnote to History: The U.S. Army at Promontory, Utah, May 10, 1869 (Paul L. Hedren, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49 No. 4, 1981; ©Utah State Historical Society)

A Plan for the Interpretation of Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah (1990)

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Golden Spike National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009-206 (Walter Fertig, May 2009)

Consensus Determination of Eligibility for the Addition of Two Features, replicas of Central Pacific Railroad Jupiter and Union Pacific Railroad No. 119, to Golden Spike National Historic Site (Doug Crossen, June 4, 2008)

Cultural Landscape Report, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Box Elder County, Utah (HTML edition) Cultural Resources Selections, Intermountain Region No. 16 (Carla Homstad, Janene Caywood and Peggy Nelson, 2000)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Golden Spike National Historic Site Cultural Landscape (1999, revised 2002)

Cultural Resources Overview and Preservation Recommendations: Promontory Route - Corrine to Promontory, Utah Cultural Resources Report No. 1034 (Michael R. Polk, November 10, 1998)

Drinking water source protection plan, Golden Spike National Historic Site (L. Martin, 1999)

Driving the Last Spike At Promontory, 1869 (J.N. Bowman, California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 36 No. 2, June 1957)

Driving the Last Spike At Promontory, 1869 (Concluded) (J.N. Bowman, California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 36 No. 3, September 1957)

Foundation Document, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah (November 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah (November 2017)

General Management Plan, Golden Spike National Historic Site/ Utah (December 1978)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Golden Spike National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2006/010 (July 2006)

Golden Spike/Crossroads of the West, National Heritage Area Final Study Report (February 2008)

Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah: Historic Handbook #40 (HTML edition) (Robert M. Utley and Francis A. Ketterson, Jr., 1969)

Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah: Historic Handbook #40 (Robert M. Utley and Francis A. Ketterson, Jr., 1969, reprint 1982)

Historic Moments: Driving the Last Spike of the Union Pacific (Sidney Dillon, Scribner's Magazine, Vol. 12, July-December 1892)

Historical Base Map and Documented Narrative 1869, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah (F.A. Ketterson, Jr., September 10, 1969)

Historic Structures Report: Railroad Trestles, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Promontory, Utah (David G. Battle, June 1971)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Golden Spike National Historic Site, 2006 (Daniel J. Stynes, May 2008)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Golden Spike National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR-2022/2419 (Dustin Perkins, June 2022)

Junior Fireman (Ages 5 and under), Golden Spike National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Program, Golden Spike National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Golden Spike National Historic Site Junior Ranger Program (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Central Pacific Railroad Grade Historic District (Douglas S. Dodge, November 1986)

Golden Spike National Historic Site (Promontory Summit) (Rickey L. Hendricks and James C. Gott, c1988)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Golden Spike National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR-2018/1777 (Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers and Mark Brunson, October 2018)

Park Newspaper (Trans-Continental): 1999 • 2003

Promontory Summit, May 10, 1869 A History of the Site Where The Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads Joined to Form the First Transcontinental Railroad, 1869, With a Special Focus on the Tents of May 10, and with Recommendations for Interpretation of and Historic Furnishings Study for the Tents at the Last Spike Site, Golden Spike National Historic Site, Utah (Robert L. Spude and Todd Delyea, 2005)

Rails East to Ogden: Utah's Transcontinental Railroad Story Utah BLM Cultural Resource Series No. 29 (Michael R. Polk and Christopher W. Merritt, 2021)

Rails East to Promontory: The Utah Stations (HTML edition) Utah BLM Cultural Resource Series No. 8 (Anan S. Raymond and Richard E. Fike, 1981, reprinted 1994)

Rendezvous at Promontory: A New Look at the Golden Spike Ceremony (Michael W. Johnson, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 72 No. 1, 2004; ©Utah State Historical Society)

Report on the Investigation of the Golden Spike Site, Promontory, Utah (John O. Littleton, March 1954)

Special Report on Promontory Summit, Utah (Golden Spike National Historic Site) (Robert M. Utley, February 1960)

Statement for Management — Golden Spike National Historic Site: April 1985 • September 1988 • January 1990

The Big Fill Trail (Ed De Leonardis, June 22, 2019)

The Dash to Promontory (Robert M. Utley, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 85 No. 4, 2017; ©Utah State Historical Society)

The Driving of the Golden Spike: The End of the Race (Bernice Gibbs Anderson, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24 Nos. 1-4, 1956; ©Utah State Historical Society)

The Golden Spike: A Centennial Remembrance American Geographical Society Occasional Publication No. 3 (E. Roland Harriman, Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Henry V. Poor, Lewis W. Douglas, James Douglas and Lynn S. Mullins, 1969, ©American Geographical Society)

The Golden Spike Is Missing (Robin Lampson, extract from The Pacific Historian, Vol. 14 No. 1, Winter 1970; ©University of the Pacific for the Holt-Atherton Pacific Center for Western Studies)

The Last Spike is Driven (Utah Historical Quarterly, volume 37, number 1, Winter 1969; ©Utah State Historical Society)

The Last Spike is Driven: A Reenactment Script for the Golden Spike Ceremony (May 2001)

The National Park Service Moves Toward Responsibility for the Golden Spike National Historic Site, 1957-1965 (R.L. Jensen, March 1969)

Transcontinental Railroad Backcountry Byway Junior Ranger (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Transportation History: The Development of Golden Spike National Historic Site-A History of Its Creation (Elmer Hanover, December 16, 1996)

Treatment Report: Promontory Trestle Stabilization at Golden Spile National Historic Site (University of Vermont and University of New Mexico, December 2012, rev. March 2013)

T-Rex, Schmee-Rex: The Building of the Transcontinental Railroad (David Emrich, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 63 No. 4, July-August 2007; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Union Pacific Locomotive #119 and Central Pacific Locomotive #60, Jupiter at Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869 (Roy E. Appleman, July 1966)

Vascular Plant Species Discoveries in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Update for 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2012/582 (Walter Fertig, Sarah Topp, Mary Moran, Terri Hildebrand, Jeff Ott and Derrick Zobell, May 2012)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Golden Spike National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2011/508 (Janet Coles, Aneth Wight, Jim Von Loh, Keith Schulz and Angela Evenden, November 2011)

Women and the Transcontinental Railroad Through Utah, 1868-1869 (Wendy Simmons Johnson, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 88 No. 4, Fall 2020, ©Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois and Utah State Historical Society)

gosp/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025