|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Montana |

|

NPS photo | |

Cowboys and Cattlemen

Wide open spaces, the hard-working cowboy, his spirited cow pony, and vast herds of cattle are strong symbols of the American West. In 1972 Congress set aside Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site as a working cattle ranch that preserves these symbols and commemorates the role of cattlemen in American history.

Cattle were introduced to the American Southwest by the Spanish in the early 1500s. British colonists brought cattle to North America's East Coast in the 1600s. Water and land made the difference between farming methods in the East and the open-range methods of the West. In the East abundant rainfall created pastures that could support large herds of cattle. Some western lands received fewer than 10 inches of rainfall a year and required over 100 acres to sustain each cow.

Before barbed wire, stockmen couldn't fence enough acreage to support livestock. Instead, a system of open-range grazing evolved. Cattle were turned out on public land and left to graze wherever they found grass. Limited in their roaming only by rivers, rough country, or waterless stretches, the cattle might spread over a million acres. Cattle from many owners mingled, leading to the establishment of roundup associations and grazing districts. As the open-range system expanded north from its roots in the Southwest, American cowboys learned herding, roping, and other skills from the Spanish vaquero, even adapting that word to buckaroo.

Cattle Barons—a New Breed of Entrepreneur

In the mid-1800s mining, timber, land, and business opportunities

brought a flood of immigrants and fortune seekers west. The

transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869, helped expand industries.

Burgeoning towns in the West and East needed food, and a new style of

businessman took hold—the cattle baron. Johnny Grant and Conrad

Kohrs were among them. In 1859 Grant drove 400 cattle from Deer Lodge

Valley, Montana, to Sacramento, California. By the 1880s Kohrs was

shipping 10,000 cattle annually by rail to stockyards in Chicago. But

the rapidly expanding cattle industry had problems. Harsh weather,

disease, rustling, economic fluctuations, homesteaders, and fencing took

their toll on what had begun as a get-rich-quick scheme.

Cattlemen adapted. Each state had its stockgrowers association, with a national association looking after their interests in Washington, DC. Research found causes of devastating cattle diseases, and vaccines decreased losses from them. State and federal legislation and programs came to regulate the industry. Land management changed, too. Grazing on public land—free in the boom years—became subject to fees. Many open-range cattle outfits faded as the West became settled, fenced, and farmed. Yet even today, cattle graze on hundreds of thousands of acres of public and private land in the West—and the American cowboy still rides.

Jesse Chisholm (1805-68)

Scot-Cherokee, famous interpreter, trader. He traveled to his trading posts on a trail that became his namesake. This trail carried nearly half of all cattle driven from Texas to Kansas.Oliver Loving (1812-67)

Trader, pioneer of cattle drives. He sent first herd of Texas longhorns to a northern market in 1858. This venture was successful, so he traded for more cattle, building large herds for market.Charles Goodnight (1836-1929)

Cowboy, cattle baron, founder of JA Ranch in Texas, inventor of chuck wagon. In 1866 he and Loving, 18 cowboys, and 2,000 longhorns blazed a new trail from Texas to Denver.Capt. Richard King (1824-85)

Livestock capitalist, founder of King Ranch in Texas. He supplied beef and provisions to Confederates during Civil War and used his war profits to amass nearly one million acres.John Chisum (1824-84)

Cattleman. His empire bordered 150 miles of the Pecos River in New Mexico. By 1875 over 80,000 cattle bore his Jinglebob earmark—an ear notch that caused a portion to dangle.John Wesley Illiff (1831-78)

Merchant, cattleman, banker. In 1870s his business sold beef to railroad crews, miners, and Indian agencies. He could ride all week (one way) without leaving his ranch lands in Colorado.Granville Stuart (1834-1918)

Co-owner of DHS Ranch. In 1883 Bielenberg and Kohrs bought a major part of the ranch, the largest cattle deal to date in Montana. His journals include drawings of Montana life.Conrad Kohrs (1835-1920)

Dream back beyond the cramping lanes to glories that have been—the camp smoke on the sunset plains, the riders loping in: Loose rein and rowelled heel to spare, the wind our only guide, for youth was in the saddle there with half a world to ride.

—From The Passing of the Trail by Badger Clark, poet of the American West and Poet Laureate, South Dakota, 1937-57

Life of the Cowboy

Often small and wiry, usually in his teens or early twenties, the open-range cowboy craved the adventure of trailing cattle hundreds of miles and the challenge of rounding up half-wild stock on the unfenced range. The work was hard—a long day in the saddle and watching the herd at night, with no days off. But it was balanced by companionship, hearty meals at the chuckwagon, and the promise of $30 or $40 at the end of a long cattle drive—plenty for a trip to town.

From his high-crowned hat and silk bandana to his leather chaps and jingling spurs, a cowboy's outfit proclaimed him part of an independent breed. The horses he rode may have belonged to his employer, but his saddle was his own—an item of such pride that to say he had "sold his saddle" meant his cowboy and trail days were over.

Written in Fire—Brands and Ownership

A rancher's brand was his reputation, his cowboys' pride, and his cows' return address. More than 50,000 brands were registered in Montana by 1900. When cattle from different owners mix together there must be a way of identifying them, and a registered brand is as individual as a license plate.

During open-range days, tens of thousands of animals from hundreds of owners mingled on common ranges. Each spring ranchers worked together to gather all the cattle in a roundup district. Cowboys heated the rancher's branding irons in a fire. When an unbranded calf was separated from the bunch, its mother naturally came to protect it. Her brand was called out and that iron taken from the fire and applied to the calf. The calf was also earmarked, a specific notch cut into its ear for extra identification. Today 98 percent of Montana cattle are still branded, but earmarking is rarely practiced.

Kingdom of Cattle

Conrad Kohrs was the Cattle King of Montana, but it was a kingdom without borders and his subjects were the cattle that ranged freely across millions of acres of public land. Born in Germany in 1835, Kohrs left home at 15 and sailed the world as a cabin boy. The quest for gold led him to California, Canada, and, in 1862, that part of the Idaho Territory that would become southwest Montana. There he made his fortune—not by panning for gold but by raising cattle.

Other cattlemen preceded Kohrs onto the open range, and many others would follow. Johnny Grant and a handful of other early settlers had been wintering cattle in Montana's western valleys since the 1850s. Grant crossed paths with Kohrs soon after the younger man arrived in the area.

Conrad Kohrs came into the territory with only the clothes on his back and what he could carry in his bedroll—and he needed money. He had learned the rudiments of the butchering trade from relatives in New York and Iowa, and he quickly found work as a butcher's assistant. Kohrs soon owned butcher shops in many gold camps. Johnny Grant supplied cattle to his shops, and, in 1866, sold his ranch to Kohrs. Grant moved back to his native Canada, leaving a legacy of stock-raising in the sheltered, grassy valleys of southwest Montana that Kohrs carried on.

Conrad Kohrs began building his empire in Deer Lodge Valley. In time he acquired 30,000 acres at the home ranch, where he raised fine breeding stock, both cattle and horses. When the near-extinction of bison on the northern plains opened a sea of grass to cattlemen, Kohrs ranged cattle from Colorado to Canada, sharing these scattered ranges with other stockmen. The shared nature of the range required close cooperation among all cattlemen and led Kohrs and other ranchers to found the Montana Stockgrowers Association in 1884.

For the next quarter of a century Kohrs and his half brother, John Bielenberg, were influential in the evolution of the cattle industry and the politics of Montana. Kohrs was a delegate to Montana's constitutional convention of 1889 and helped draft the constitution that led to statehood.

As the open-range system declined, Kohrs adapted his business to a mix of farming and open-range grazing. In 1909, long after the boom years, Kohrs' cattle sales topped $500,000. In later years he sold off most of his holdings, having achieved his version of the American dream. Conrad Kohrs died in 1920, and John Bielenberg in 1922. For a time the ranch was run by a family trust. In 1932 Kohrs' grandson, Conrad Warren, began a new era as manager and then, in 1940, as owner of the ranch.

Settling the Valley

The mountain valley Johnny Grant settled in 1859 was a land caught between eras and cultures. Considered Flathead (Salish and Kootenai) territory by the federal government the valley had long been used by many tribes as a route to hunting and trading areas. Early pioneers that settled in Deer Lodge Valley were Mexican and Métis, a cultural blend of French-Canadian and tribal people, attracted by fur trading. As the fur trade faded into memory, gold mining and livestock industries attracted new settlers.

Johnny Grant (1831-1907)

His marriage to women of several tribes helped ensure his peaceful settlement in the valley.

Powerful Partnerships

John Bielenberg was Conrad Kohrs' younger half brother and a full partner in their diverse business interests. Kohrs spent much of his time on mining, water rights, banking, and the public life of an entrepreneur. Bielenberg concentrated on the daily management of their cattle empire. He sought to improve the breeding of horses and cattle. Crossing Thoroughbred studs with native mares, he bred cow ponies famed for stamina. His 1900 observation about cattle, "Herefords are the coming breed for Montana," was prophetic.

John Bielenberg (1846-1922)

John Bielenberg was Kohrs' half brother and business partner, and an expert cattleman. He lived in the ranch house for half a century, but he often preferred the informality of the bunkhouse.

Furthering a Legacy

Conrad Kohrs Warren was born into one of the most famous ranch families of the 1800s, but the days of open range and cattle drives were over. When he began managing the Kohrs ranch in 1932, only 1,000 acres and a few hundred head of cattle remained. He ran the ranch with methods of the new century while honoring his family's ranching legacy. In 1952 he was elected president of the Montana Stockgrowers Association that his grandfather helped found 66 years earlier.

Conrad K. Warren (1907-1993)

Warren was renowned for his love of animals, commitment to the livestock industry, and resolve to preserve the ranch, artifacts, records, and lore of his grandfather and great uncle.

Home on the Range

There was not just one home on the range but many, from a simple dugout gouged out of a hillside and faced with rough-hewn logs to the elegant mansions of the cattle kings. Johnny Grant described his first home in the valley as a leather lodge (a tepee) that he got from an Indian in exchange for a horse. Conrad Kohrs called his first butcher shop a brush shanty. Each must have felt pride in his new home, from the original 4,000-square-foot house that Grant built in 1862 to the 5,000-square-foot brick addition Kohrs built in 1890.

Augusta Kohrs came to a finer home than many pioneer brides. Still, when she arrived in 1868, the interior of the house was a far cry from its later Victorian elegance. The bride discovered a house with bare floors, spittoons, and an old bed strung with rawhide in place of springs, and a straw-filled sack for a mattress infested with bedbugs. She began "a war of extermination" using boiling water and kerosene until the bugs disappeared except for "an occasional one left by a chance traveler." Over time she acquired fine furniture, a piano, china, silver, gilt-framed pictures, and Persian rugs. The 1890 addition of her conservatory filled her heart with joy.

Shelter, warmth, companionship, and food were essentials for frontier life. If the Kohrs served champagne and oysters to guests on special occasions, it is likely that a hungry cowboy riding the grubline ate with no less enjoyment when invited into the bunkhouse for coffee, beef, beans, and biscuits. Amusements were similar too. Kohrs played cards with his friends on a special felt-covered poker table, while out in the bunkhouse cowboys played cribbage and cards over a scarred worktable, and on the open range cowboys dealt cards across a blanket on the ground.

For ranchers less prosperous than the Kohrs the line between family and hired hand wasn't always so obvious. They spent much time together. Work filled their days; songs, stories, and conversations filled idle hours. Chores were necessary for comfort, even survival. One element missing from both bunkhouse and open range was family. For many cowboys, some little older than children themselves, roundups and trail drives were often their first time away from home. Theirs could be a lonely life.

Old World Meets New

Her childhood in Hamburg, Germany, did little to prepare Augusta Kruse Kohrs for her life as a pioneer bride. She milked cows, made soap and candles, cooked, and kept house for hired hands and her husband. Yet she preserved much of the heritage of her former homeland. As the family prospered she acquired fine belongings, supervised a staff, and valued both the New and the Old World, balancing the opportunities of America with the music, art, and culture of Europe.

Augusta Kohrs (1849-1945)

Proud, tall, and beautiful, 25-year-old Augusta poses for a portrait. She and Conrad met when children in Germany. They married in Iowa on February 23, 1868, after dating for about three weeks.

A Frontier Family

The upbringing of the Kohrs children differed from that of many ranch children. They had a governess, learned German, and traveled abroad. Chores common to many children—chopping wood, pumping water, feeding livestock—were not part of their routine. Anna and Katharine learned needlepoint; William showed a talent for art. Anna kept close ties with ranching by marrying John Boardman, a rancher associated with Kohrs in livestock enterprises. In the end it was Katharine's son, Conrad Warren, who saved the ranch and was most at home on the range.

Preserving a Way of Life

Sometimes it takes someone from outside the story to see the importance of a family's history. It was Nell, Conrad Warren's wife, who began recording the family history she had learned from Augusta. Nell cared for their extraordinary collection of antiques and documents, while her husband concentrated on ranching in difficult times that included the Great Depression and World War II. She also urged her husband to contact the National Park Service as they sought to preserve the historic Grant-Kohrs ranch beyond their lifetimes.

Nell Warren (1911-79)

Nell protected the possessions of Kohrs and Bielenberg, and compiled a history of their businesses. Her efforts preserved a rare, intact record of the cattle industry that spans nearly 150 years.

Moseying Around: The Ranch Today

Exploring the Grounds You are invited to tour the ranch on your own. Please notice that firearms are prohibited in the visitor center and buildings 1, 4, 10, 11, 15, and 16.

Take time to notice little things—feel fresh air on your face, listen for birds, count colors in the sky and fields, observe textures of wood and leather, smell the aroma of horses and hay.

Beyond the Clark Fork River (named for William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition) rises the Flint Creek Range, with Mount Powell the highest at 10,200 feet. In winter these mountains catch much of the eastbound storms, leaving the valley relatively free of snow. This is one reason why Grant and Kohrs settled here—their cattle and horses could graze all winter in "this luxuriant grassy valley."

Ranch House (1862-90)

Johnny Grant built the white portion of the house in 1862. It was a

trading post downstairs and a residence upstairs. In 1890 Conrad Kohrs

built the brick wing with a formal dining room, large kitchen, a second

bathroom, and bedrooms. Augusta Kohrs acquired elegant furnishings over

several decades. Coal to heat the house was stored in the shed behind

the back door of the brick addition.

Bunkhouse Row (1907-1930s)

Cowboys and ranch hands ate and slept here and whiled away evening hours

swapping stories, mending gear, and playing cards.

Ice House/Tack Room (1880s-1930s)

Ice cut from ponds in winter was stored here for summer use. When

refrigeration came in 1935, the ice house became a tack room for horse

gear. The added room was the summer home of Ham Sam, the Chinese

cook.

Garage/Blacksmith Shop (1935)

Conrad Warren stored gas-powered vehicles here. It also served as a

repair shop and a place to shoe horses.

Leeds Lion Barn (1885)

There are several stallion barns on the ranch, each with its own hay

loft and corral. To prevent fighting each barn stabled only one

stallion. This barn was named for a famous English Shire draft horse

stallion owned by Kohrs.

Feed Lot and Sheds (1930s)

Con Warren added this part of the ranch when he began raising Hereford

cattle.

Buggy Shed (1883)

This shed once adjoined the east end of bunkhouse row. It was moved in

1907 to make way for the railroad tracks.

Granary (1935)

Grains (oats, corn) were ground and mixed for cattle feed, then stored

here.

Thoroughbred Barn (1883)

Kohrs built this as a stable for Thoroughbreds. Conrad Warren used it

for his show cattle. Today it houses horse-drawn vehicles and equipment

original to the ranch.

Chicken Coop (1930s)

Chickens provided meat and eggs. Hens laid eggs in nesting boxes, pecked

for food in the yard, and perched on roosting bars at night.

Draft Horse Barn (1870)

Kohrs and Bielenberg raised several breeds of draft horses—Shires,

Percheron-Normans, and Clydesdales—to do the heavy chores.

Dairy (1932)

Dairy cows were milked here. In the 1930s Conrad Warren sold milk to

Deer Lodge Creamery.

Oxen Barn (1870)

After draft horses replaced oxen, this barn sheltered other livestock

but kept its name.

Bielenberg Barn (1880)

Young cows having their first calves were often kept here so that ranch

hands could make sure the calving (birthing) went well.

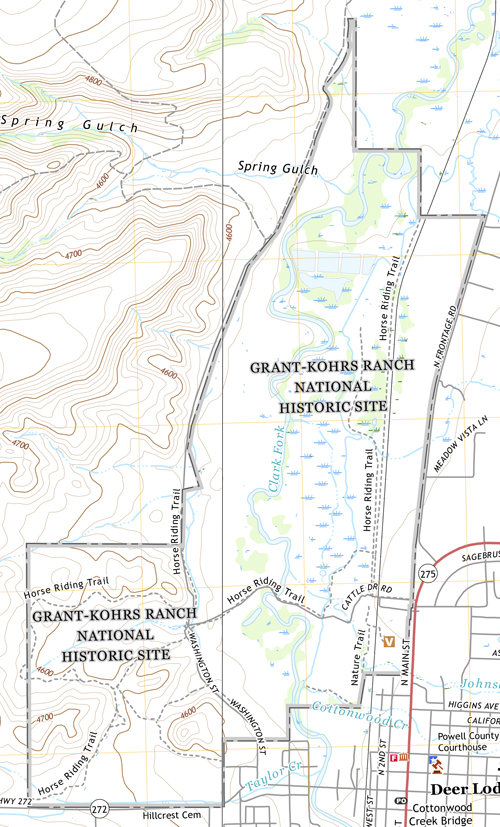

(click for larger maps) |

Warren House (1934)

Conrad and Nell Warren's house was a wedding gift from Conrad's

grandmother, Augusta Kohrs. Today it holds park administrative

offices.

Warren Barn (1950s)

The barn housed hay, grain, and Con Warren's prize Herefords.

Beaver Slide Hay Stacker

In August, this horse-run stacker piles hay into 50-ton stacks.

Railroad Tracks

Utah Northern Railroad arrived in 1879; the Milwaukee Railroad came in

1907.

Fences

Look for three styles of fences: Pickets enclose the ranch house; boards

and barbed wire mark pastures; jacklegs (rails on crossed posts) were

the main style on early Montana ranches.

Irrigation Ditches

The Kohrs-Manning Irrigation Ditch dates from the 1870s.

Trails

Ask at the visitor center for maps of the nature trail, the Old

Milwaukee Trail, or the trail to far pastures.

About Your Visit

Visitor Center Start here for information and to sign up for a tour of the ranch house. The visitor center and ranch are open daily, except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

Guided Tours of the House The only way to see the ranch house is with a guided tour. Tour size is limited, and you may have to wait. You may visit the grounds until your tour begins.

Activities This is a working ranch (not a dude ranch or petting farm) with year-round chores directed by the seasons. The ranch can bustle with activities (branding, haying, and more) or seem quiet. Programs and ranger-led activities are offered seasonally. Visit our website to find out about special events.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Safety and Regulations Please help us preserve this park • Smoking and pets are allowed only in the parking lot. • Do not touch historic objects. • Stay in designated areas and watch where you walk. • Livestock can be unpredictable; do not approach livestock. • Do not climb on fences or enter corrals or pastures. • Close gates behind you. • Be careful on the railroad tracks; the east track is active. • All historic and natural features are protected by federal law. • For general firearms regulations, check the park website.

Beyond the Ranch

Grant-Kohrs-related sites in Deer Lodge, MT:

• The 1910 home of Nicholas Bielenberg (brother of John and half

brother of Conrad Kohrs), 801 Milwaukee Ave.

• William K. Kohrs Library, 501 Missouri Ave. William, Conrad

Kohrs' only son, died in 1901.

• Hillcrest Cemetery, W. Milwaukee Rd. Burial sites for Augusta,

Conrad, son William Kohrs, John Bielenberg, and grandson Conrad

Warren.

• Old Prison Museum, 1106 Main St. Site of the Montana Territorial

Prison. Kohrs served on the board of prison commissioners in the

1870s.

Kohrs-related sites in Helena, MT:

• Home of Conrad and Augusta Kohrs, 804 Dearborn Ave., purchased in

1900.

• Montana Historical Society Museum, 225 N. Roberts St. Collection

of oils, watercolors, bronzes, and illustrated letters by artist Charles

M. Russell.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site — August 25, 1972 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Field Guide to the Wildlife and Habitats of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch (Gary Swant, Date Unknown)

Application of Surrogate Technology to Predict Real-Time Metallic-Contaminant Concentrations and Loads in the Clark Fork near Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana, Water Years 2019-20 U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2023-5021 (Christopher A. Ellison, Steven K. Sando and Tom E. Cleasby, 2023)

Bird Monitoring Project: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Katie Atkinson and Kristina Smucker, 2013)

Comprehensive Interpretive Plan, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (2002)

Conrad Kohrs—Cattleman (concluded) (Herbert P. White, extract from The Denver Westerners Monthly Roundup, Vol. 15 No. 12, December 1959; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Conrad Kohrs—Cattleman (continued) (Herbert P. White, extract from The Denver Westerners Monthly Roundup, Vol. 15 No. 11, November 1959; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Cowboy Poetry & Songbook (Laura Rotegard and Lyndel Meikle, comps., 2008)

Cultural Landscape Report, Part Two, Pasture/Hay Fields and Upland Pastures, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Shapins Belt Collins, February 2009)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Landscape (2007)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Kohrs Ranch House and Yard (2004)

Cultural Soundscape of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS (Robert C. Maher, March 2010)

Flood Plain Vegetation Changes on the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Between 1993 and 2000 (Don Bedunah and Thad Jones, November 27, 2001)

Foundation Document, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana (June 2008)

Foundation Document Overview, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana (July 2014)

From Butcher Boy to Beef King: The gold camp days of Conrad Kohrs (Larry Gill, extract from Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 8 No. 2, Spring 1958)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan Environmental Impact Statement/Cultural Landscape Inventory and Analysis, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Powell County, Montana (March 1993; Thomas G. Keohan, 1991)

Geologic Map of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana (February 2019)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2007/004 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, June 2007)

Geologic, Soil Water and Groundwater Report — 2000, Grant Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Johnnie N. Moore and William W. Woessner, February 21, 2001)

Grant Kohrs Ranch Fence Report (Philip B. Davis and Lisa Rew, March 2011)

Historic Context Report: Thomas Stuart Homestead, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Avana Andrade, February 1, 2012)

Historic Furnishing Study, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana (Nick Scrattish, April 1981)

Historic Resource Study/Historic Structure Report/Historical Data, Kohrs and Bielenberg Home Ranch, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (HTML edition) (John Albright, October 1979)

Interpreting the Cattle Baron: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Deer Lodge, Montana (Rodd L. Wheaton, extract from NCPH Public History News, Vol. 13 No. 3, Spring 1997)

John "Johnny" Francis Grant (1831-1907) (Lawrence Barkwell, Date Unknown)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Junior Rancher Activity Book (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Honorary Rancher Program (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Museum Management Plan, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (September 2009)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Grant-Kohrs Ranch (Ann Huber, Dawn Bunyak and Christine Whitacre, August 31, 2001)

Grant-Kohrs Ranch/Warren Ranch (Ann Huber, Dawn Bunyak and Christine Whitacre, January 4, 2002)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRKO/NRR-2015/1071 (Kathy Allen, Sarah Gardner, Kevin Benck, Andy Nadeau, Lonnie Meinke, Thomas Walker, Mike Komp, Keaton Miles and Barry Drazkowski, October 2015)

Newsletter (Ranch Roundup): Vol. V No. 3, Winter 2007 • Vol. VIII No. 1, Winter/Spring 2009 • Winter 2011

Photographs, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Montana Memory Project)

Ranchers to Rangers: An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Douglas C. McChristian, July 1977)

Resource Management Plan, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (January 1995)

Rocky Mountain Network News and Highlights, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Spring 2008)

Small Mammal Surveys on Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Final Report (Dean E. Pearson, Kathryn A. Socie and Leonard F. Ruggiero, February 2, 2006)

Statement for Management, Grant Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (October 1995)

Superintendent's Annual Report: FY2004 — The nation's ranch and a ranch for all seasons, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Laura Rotegard, March 2005)

Superintendent's Annual Report: FY2005, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (Laura Rotegard, March 2006)

Summary of 2010 Bird Surveys — Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Park: Stuart and Taylor Field Sites (Matthew Larson, March 1, 2011)

The Building of a Cattle Empire: The Saga of Conrad Kohrs (Herbert P. White, extract from The Denver Westerners Monthly Roundup, Vol. 15 No. 10, October 1959; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR—2012/589 (Peter Rice, Will Gustafson, Daniel Manier, Brent Frakes, E. William Schweiger, Chris Lea, Donna Shorrock and Laura O'Gan, October 2012)

Vegetation Composition, Structure, and Soils Monitoring at Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site: Data Report 2010-2014 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR-2016/1211 (Erin M. Borgman, May 2016)

Vegetation Composition, Structure, and Soils, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site: 2009–2019 Status and Trend NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR—2022/2387 (Erin M. Borgman and Jason F. Smith, May 2022)

grko/index.htm

Last Updated: 12-May-2025