|

GRAND TETON

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

GRAND TETON

National Park

• OPEN FROM JUNE 2 TO OCTOBER 15 •

THE GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK embraces the most scenic portion of the Teton Range of Wyoming, with an area of approximately 150 square miles, or 96,000 acres. It varies from 3 to 9 miles in width and is 27 miles in length. The northern extremity of the park is about 11 miles south of the southern boundary of Yellowstone National Park. This park was established by President Coolidge on February 26, 1929.

In addition to its sublime peaks and canyons, the Grand Teton National Park includes six large lakes and many smaller bodies of water, glaciers, and snowfields, and extensive forests of pine, fir, spruce, cottonwood, and aspen. However, much of the park area is above timberline (10,500 feet), the Tetons rising 3,000 to more than 7,000 feet above the floor of Jackson Hole.

The great array of peaks which constitutes the scenic climax of this national park is one of the noblest in the world. It is alpine in the truest sense. Southwest of Jenny Lake is a culminating group of lofty peaks whose dominating figure is the Grand Teton, the famous mountain after which the park takes its name. The resemblance of this group, whose clustered, tapering spires tower aloft to a height of thousands of feet and are hung with never-melting snowfields, to a vast cathedral, must suggest itself to every observer.

However widely traveled, visitors viewing the Tetons for the first time confess that the beauty of this park and the rugged grandeur of its mountains come to them as a distinct revelation. This is amply proved by the increasingly large number of visitors who return summer after summer to spend their vacations in the Grand Teton National Park. The recreational possibilities of these mountains, they have found, are practically limitless. Here they may camp on the lakes, swim and fish, ride or hike the trails, engage in the strenuous sport of mountaineering, or—if their needs and wishes so dictate—simply relax and rest.

The Teton Range. Copyright, Crandall.

The Grand, Middle, and South Tetons comprise the historic Trois Tetons, which were noted landmarks to the trappers and explorers of the early nineteenth century. The Three Tetons are seen to best advantage from the west and southwest. As the observer's viewpoint is shifted, the major peaks change greatly in outline and relative position, but despite this fact one soon learns to recognize each.

Eleven peaks are of such boldness and prominence that they receive rank as major peaks. In order of descending altitude they are: Grand Teton, 13,766 feet; Mount Owen, 12,922; Middle Teton 12,798; Mount Moran 12,594; South Teton, 12,505; Mount Teewinot, 12,317; Buck Mountain, 11,923; Nez Perce, 11,900; Mount Woodring, 21,585; Mount Wister, 11,480; and Mount St. John, 11,440.

In addition to the 11 major peaks there are an even larger number of somewhat lesser prominence and altitude, such as Cloudveil Dome, 12,026 feet; Eagles Rest, 11,300; Table Mountain, 11,075; Bivouac Peak, 11,000; Prospectors Mountain, 11,000; Rockchuck, 11,000; Rolling Thunder, 10,900; Housetop Mountain, 10,800; Rendezvous Peak, 10,800; Mount Hunt, 10,775; Symmetry Spire, 10,500; and Storm Point, 10,100, as well as a host of nameless pinnacles and crags which serve still further to make the Teton skyline the most jagged of any on the continent.

The larger lakes of the park, Leigh, Beaver Dick, Jenny, Bradley, Taggart, and Phelps, all lie close to the foot of the range and, like beads, are linked together by the sparkling, tumbling waters of Cottonwood Creek and neighboring streams. Nestled in dense forests outside the mouths of canyons, these lakes mirror in their quiet depths nearby peaks whose pointed summits rise with sheer slopes a mile or more above their level.

HISTORY OF THE REGION

Many of our national parks have been carved from wilderness areas previously little known to man and but seldom visited. The Tetons, on the contrary, are remarkably rich in historic associations. The Grand Teton itself has been referred to by an eminent historian as "the most noted historic summit of the West."

Up to the beginning of the last century Indians held undisputed sway over the country dominated by the three Tetons. Then as now Jackson Hole was literally a happy hunting ground, and, while the severe winters precluded permanent habitation, during the milder seasons bands of Indians frequently came into the basin on hunting or warring expeditions. They represented many tribes, usually hostile to each other. The dreaded Blackfeet, the Crows, the Nez Perce, the Flatheads, the Shoshoni, and others. There is little reason to believe that these Indians ever invaded the more rugged portions of the Tetons, but it is certain they regularly crossed the range, utilizing the several passes.

The Tetons probably first became known to white men in 1808, in which year the intrepid John Colter crossed the range, presumably near Teton Pass on the memorable journey which also made him discoverer of the Yellowstone country. In 1811 the Astorians, under Wilson Price Hunt, entered Jackson Hole by the Hoback Canyon and, failing in an attempt to navigate the Snake River, likewise crossed the Teton Range in the vicinity of Teton Pass, continuing thence to the mouth of the Columbia, where the trading post, Astoria, was founded. The Tetons also figure in the adventures of the returning Astorians in 1812. In Washington Irving's classic account of the Astorian expedition (Astoria, published in 1836) the name "Tetons" first appears in literature.

The decades which follow may truly be referred to as "the Fur Era", for the Tetons became the center of remarkable activities on the part of fur trappers representing both British and American interests, the former by the Northwest and Hudson's Bay Companies, the latter by a succession of companies operating out of St. Louis, Mo. "It was the trio of peaks so distinctively presented from the west and southwest that made the Tetons famous as landmarks among the roving trappers who, guiding their courses by these easily recognized summits, singly or in groups passed over Teton Pass and through Pierres Hole in their seasonal migrations to and from their remote hunting grounds." Could these ancient monuments speak they "would make known some of the most interesting events in the annals of the fur trade. For this was the paradise of the trapper. In every direction meandered the streams along which he pursued his trade, and nearby were the valleys where the rival companies gathered in annual conclave to fight the bloodless battles of their business. There is scarcely an acre of open country in sight of it that has not been the scene of forgotten struggles with the implacable Blackfeet, while far and near, in unknown graves, lie many obscure wanderers of whose lonely fate no record survives." Captain Bonneville, Father DeSmet, Rev. Samuel Parker, Jedediah Smith, Bridger, Kit Carson, David Jackson (after whom Jackson Hole and Jackson Lake were named), Sublette, Joe Meek—these are names to conjure within western history! These and many others equally distinguished appear in the records of the Teton country, particularly in the third and fourth decades of the century. The 1832 rendezvous of the American trappers was held in Teton Basin, then known as "Pierres Hole", at the foot of the Tetons; it was attended by many of the most famous trappers of the time, and furnished occasion for the Battle of Pierres Hole, a notable engagement between the trappers and Blackfeet.

The picturesque name "Jackson Hole" dates back to 1828, in which year Capt. William Sublette so named it after his fellow trapper, David E. Jackson, who was especially partial to this beautiful valley. The term "hole" was used by the trappers of that period in much the same sense as is the word "basin" today, being applied to any mountain-girt valley.

In the 1840's the value of beaver skins declined and with it the fur trade. By 1845 the romantic trapper of "the Fur Era" had vanished from the Rockies—not, however, without having won for himself an imperishable place in American history. During the next four decades the valleys near the Tetons were largely deserted, except for wandering bands of Indians that still occasionally drifted in. But the frontier was relentlessly closing in, and one Government expedition after another passed through the Teton country or skirted its borders. Most important of these were the Hayden surveys, which in 1871, 1872, 1877, and 1878 sent parties into the region. The names of several members of the 1872 expedition are perpetuated in connection with Leigh, Beaver Dick, Jenny, Bradley, Taggart, and Phelps Lakes. Orestes St. John, geologist with the 1877 Hayden party, and the great artist, Thomas Moran, who in 1879 went with a military escort to paint the Tetons, are similarly remembered in the names of two of the principal peaks. To this transition period also belong the earliest prospectors of Jackson Hole, as well as several famous big-game hunters who came here in search of trophies—forerunners of the hundreds of hunters who now annually invade this region.

In the middle eighties came the first settlers. They entered by the Gros Ventre River and Teton Pass, and to begin with naturally settled in the south end of the hole. Here as elsewhere the story of the homesteader has been one of isolation, privations, and hardship, met, however, with persistency and indomitable courage. Nor is the story confined to the past, for maintaining a livelihood amongst these mountains still calls for resourcefulness, fortitude, and—not infrequently—even heroism.

History, here, is still in the making. Teton Forest Reserve was not created until 1897; the railroad reached Victor in 1912; the Jackson Lake Dam was finished in 1911; many of the roads and bridges of the region were constructed within the past decade; and the Grand Teton National Park was created in 1929. The detailed exploration of the range and the conquest of its high peaks have taken place in relatively recent years, and since 1929 trails have been built which for the first time make the Tetons really accessible to the public.

In later paragraphs will be found an account of the mountaineering history of the Tetons. And so the dramatic human story of these mountains is brought down to the present.

A few of the park's high peaks.

GEOGRAPHIC FEATURES

THE TETON RANGE

On the Jackson Hole side the Teton Range presents one of the most precipitous mountain fronts on the continent. Except for Teton Pass, at its southern end, the range is practically an insuperable barrier. Forty miles in length, it springs abruptly from Jackson Hole and only a few miles west of its base attains elevations of more than 13,000 feet above the sea. Thus most of the range is lifted above timberline into the realm of perpetual snow, and in its deeper recesses small glaciers still linger. The grandeur of the beetling gray crags, sheer precipices, and perennial snow fields, is vastly enhanced on this side by the total absence of foothills and by contrast with the relatively flat floor of Jackson Hole, from which they are usually viewed.

The Teton Range may be described as a long block of the earth that has been broken and uplifted along its eastern margin, thus being tilted westward. Movement of this sort along a fracture is what the geologist terms "faulting." The total amount of uplift along the eastern edge of the block amounts to more than 10,000 feet. Doubtless this uplift was accomplished not by one cataclysm but by a series of small faulting movements distributed over a very long period. Probably the time of faulting was as remote as the middle of the Tertiary period (the period just before the Ice Age, the latest chapter of the earth's history).

Very impressive is the contrast between the east and west sides of the Teton Range. From the east, the Jackson Hole side, one views the precipitous side of the mountain block as it has been exposed by uplift and erosion. From the west, the Idaho side, is seen the broad top of the block, which is gently inclined toward the west. In the eastern front, furthermore, one sees the ancient, deep-seated crystalline rocks (gneiss, schist, and pegmatite) belonging to the earliest known geologic eras, the pre-Cambrian. In places on the top of the block, at the head of Death and Avalanche Canyons, for example, are seen the inclined layers of limestone, quartzite, and shale belonging to the less ancient Paleozoic era. These layers formerly covered the entire block, but they have been worn away from half of the area, thus exposing the underlying crystallines. The west and north flanks of the range are overlapped by relatively young beds of lava that are continuous with those covering eastern Idaho and the Yellowstone plateaus.

JACKSON HOLE

Jackson Hole, which adjoins the park on the southeast, is one of the most sequestered valleys in the Rockies, encompassed on all sides as it is by mountain barriers. It is 48 miles long, for the most part 6 to 8 miles wide, and embraces an area of more than 400 square miles. The floor of the valley slopes from an altitude of 7,000 feet at the north end to 6,000 at the south. Jackson Hole lies a few miles west of the Continental Divide, and occupies the central portion of the headwaters area of the Snake River. Mountain streams converge radially toward it from the surrounding highlands, and the Snake River receives these as it flows through the valley.

Jackson Hole has largely been excavated by the Snake River and its tributaries from the shale formations which once extended over the region to a depth of several thousand feet. Rocks surrounding the region, being more resistant, were reduced less rapidly and therefore have been left standing in relief as highlands.

Teton Range from Snake River. Copyright, Crandall.

THE WORK OF GLACIERS

Here, as in several other national parks, the glaciers of the Ice Age, known to the geologist as the Pleistocene period, played a leading role in developing the extraordinary scenic features. Just as the streams now converge toward Jackson Hole, so in ages past glaciers moved down toward, and in many instances into, the basin from the highlands to the east, north, and west. Detailed study has shown that the Ice Age was not a single, simple episode, but is divisible into "stages"—glacial stages, during which extensive ice fields formed, and interglacial stages, during which these were largely or wholly withdrawn. The duration of each is to be thought of in terms of tens of thousands of years. In Jackson Hole, 3 glacial and 2 interglacial stages have been recognized. Only the most recent glacial stage need concern us here, the other two having occurred so long ago that their records are much obscured.

This stage ended but yesterday, geologically speaking, and to it is due much of the grandeur of the region. In the Teton Range every canyon from Phillips northward contained a glacier, and many of these reached eastward to the base of the range where they spread widely upon the floor of Jackson Hole. Where Jackson Lake now is there lay a great, sluggish field of ice resulting from the confluence of adjacent alpine glaciers.

Moraines, outwash plains and lakes are easily recognizable features that originated during the latest glacial stages, and most of the peaks and canyons were greatly modified.

Moraines are deposits of debris, piled up by the ice itself. Such are the heavily wooded, hummocky embankments which rest along the base of the mountains from Granite Canyon northward, rising in some cases 200 or 300 feet above the floor of Jackson Hole and heaped with enormous boulders quarried by the ice far back in the range.

With two exceptions each of the large moraines incloses a lake. In this way Phelps, Taggart, Bradley, Jenny, Leigh, and Jackson Lakes originated; all ranged along the western border of Jackson Hole. No lakes were formed along the eastern border, inasmuch as on this side no glaciers extended beyond their canyons. Beaver Dick Lake is dammed in part by a gravel fill.

Outwash plains are the deposits formed by streams which, during the Ice Age, issued from the glaciers. Of this origin are the broad, cobble-strewn flats, usually overgrown with sage, which cover the floor of Jackson Hole. They are diversified by bars, abandoned stream channels, terraces and "pitted plains", features of exceptional interest to one who examines them in detail. Several isolated buttes—Signal, Blacktail, and the Gros Ventre Buttes—rise like islands a thousand feet or more above these flats.

Each canyon gives evidence of the vigor with which the glacier it once contained gouged out its channel. In many places the rock of the broad floors and steep sides is still remarkably polished. Every canyon leads up to one or more amphitheaters, or cirques, with sheer bare walls thousands of feet high. Tracing these ice-gouged canyons headward you will discover many rock-rimmed lakelets, some hung on precipitous mountain sides where one might be pardoned for asserting that no lake could possibly exist.

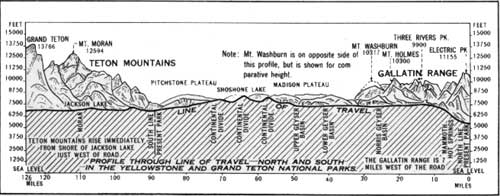

Profile of the Yellowstone-Grand Teton region.

TRAILS

An unbroken wilderness a few years ago, the Grand Teton National Park is now penetrated by some of the finest trails in the national-park system. These trails, suitable alike for travel afoot or on saddle horses, are 3 to 4 feet wide, free of boulders, and of grade so moderate they may be followed by old or young with full safety and a minimum of physical exertion.

The Lakes Trail runs parallel to the mountains, following closely the base of the range and skirting the shore of each large body of water from Leigh Lake at the north to Phelps Lake at the south. It makes accessible the most important lakes, canyons, and peaks of the park, and is, naturally, the one from which all expeditions into the range begin. By following trail and highway one can now encircle either Beaver Dick Lake or Jenny Lake, the hike around Jenny Lake being one of the most popular in the park.

The Canyon Trails, four in number, are spur trails extending westward from the Lakes Trail, back into the most rugged areas in the Teton Range. Intervening canyons have been left in their splendid wildness.

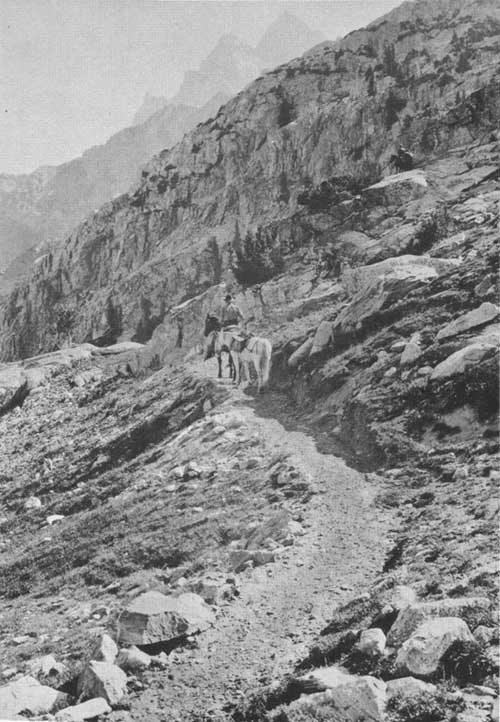

The Tetons from Upper Cascade Canyon Trail.

The Teton Glacier Trail extends up the east slope of the Grand Teton to two alpine lakes, Surprise and Amphitheater, at altitudes close to 10,000 feet. By means of the 17 switchbacks on this trail the hiker or horseman climbs to a point on the face of the Grand Teton, 3,000 feet above the floor of the valley, throughout this ascent enjoying matchless panoramas of the entire Jackson Hole country, and witnesses a view extending eastward 80 miles to the Wind River Mountains, whose peaks and glaciers are sharply outlined against the horizon. Amphitheater Lake, at the end of the trail, occupies a protected glacial cirque and is a favorite starting point for ascents of Teewinot and Mount Owen. Teton Glacier, the most accessible of the ice fields, is best reached from Amphitheater Lake, being three-fourths of a mile northwest from the end of the trail. Though seasoned hikers make the climb from Jenny Lake to the glacier by way of this trail, it is advisable for most people to take horses as far as Amphitheater Lake, and continue on foot with a guide over to the glacier.

Along the trail at the head of Cascade Canyon. Grant photo.

The Indian Paintbrush Trail starts near the outlet of Leigh Lake and follows up the bottom of Indian Paintbrush Canyon to connect with the Cascade Canyon Trail by way of Lake Solitude, a lakelet of rarest beauty at timberline near the head of the north fork of Cascade Canyon. The wealth of wild flowers along this trail gives name to the canyon, and early or late in the day one may see big game, especially moose, near the lakes and swamps. This trail affords superb views of Jackson and Leigh Lakes eastward beyond the mouth of the canyon, and westward along the Divide glimpses of snowclad ridges and peaks.

The Cascade Canyon Trail passes through a chasm whose walls rise sheer on either side for thousands of feet. By this trail one penetrates into the deepest recesses of the Tetons. It skirts the base of several of the noblest peaks, Teewinot, Mount Owen, Table Mountain, and the Three Tetons, and it enables one to see these titans not only at close range but from new and impressive angles. Lake Solitude may be reached by means of this trail, by taking the Cascade Canyon-Indian Paintbrush loop trail leading up the north fork of the Cascade Canyon.

The Death Canyon Trail traverses the full length of a canyon which in its lower portion is of profound depth and grandeur, as awesome as its name, but which above opens into broad, sunny meadows. No canyon better illustrates the difference between the rugged, alpine landscapes developed in the crystalline rock of the Teton east border and the softer contours formed in the sedimentary strata to the west, near the Divide.

The Skyline Trail.—The linking together of the Cascade and Death Canyon Trails, at their heads, took place on October 1, 1933, and marked the first step in the realization of a plan whereby the hiker and horseman will be enabled to visit that most fascinating region, the Divide, a belt of alpine country along which the waters of the range are turned either eastward into Wyoming or westward toward Idaho. Now that the first unit is completed one can ascend to the Divide by one canyon and return by the other, making a loop trip that involves no repetition of route and that will take one into the wildest of alpine country for as long a period as desired. In traversing this loop one completely encircles the Three Tetons and adjacent high peaks, viewing them from all sides. In this way one learns to know these peaks with an intimacy impossible to the visitor who contents himself with distant views. No more thrilling or enjoyable mountain trip can be found in all America than that over the newly-completed loop of the Teton Skyline Trail.

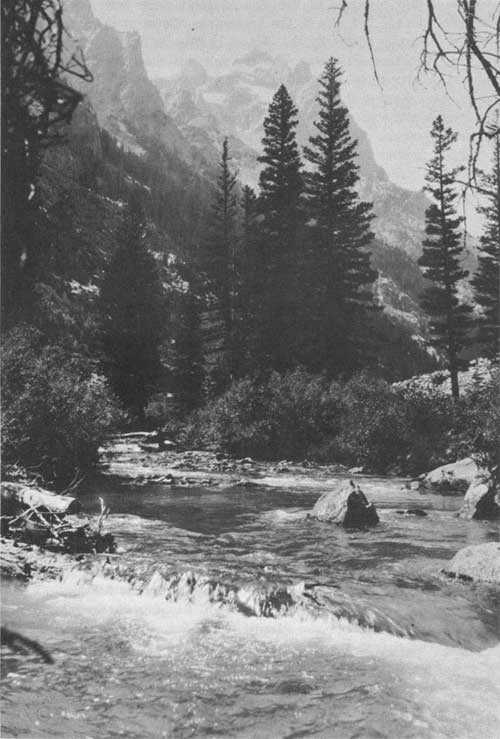

The icy waters of Cascade Canyon. Copyright, Crandall.

MOUNTAIN CLIMBING

Among American climbers no range enjoys higher rank than the Tetons, and its growing fame abroad is evidenced by increasingly large numbers of foreign mountaineers who come here to climb. Leading mountaineers unhesitatingly rank many of the Teton climbs with the best in the Alps and other world-famous climbing centers. Though the majority of climbs must be considered difficult even for mountaineers of skill and wide experience, there are several peaks, notably the Middle Teton, South Teton, and Mount Woodring, which have relatively easy routes that may be safely followed by anyone of average strength.

Although the conquest of the Tetons has largely been accomplished within the decade just closed, the beginnings of mountaineering go back nearly a century. Naturally the Grand Teton was first to be challenged, and the Wyoming historian, Coutant, records that in 1843 a French explorer, Michaud, with a well-organized party attempted its ascent but was stopped short of the summit by unscalable cliffs. It is possible that even earlier white men—trappers and explorers—matched their strength and strategy against this peak or others in the Tetons, but if so their efforts have gone unrecorded. From the period of the Hayden surveys in the seventies, accounts of several attempts have come down to us, and one party, consisting of N. P. Langford and James Stevenson, purported to have reached the summit on July 29, 1872. This claim to first ascent has been generally discredited because of the serious discrepancies between Langford's published account and the actual conditions on the peak as now known. In 1891 and again in 1897 William O. Owen, pioneer Wyoming surveyor, headed attempts to reach the summit which likewise failed. Finally in 1898 a party sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Club, of Colorado, and comprising Owen, Bishop Franklin S. Spalding, John Shive, and Frank Petersen, on August 11 discovered the traverse which, 700 feet beneath the summit, leads around the northwest face and so opens up a clear route to the top.

The conquest of the Grand Teton achieved, public interest waned and a quarter century elapsed before the peak was again scaled. In 1923 two parties retraced the route of 1898, and each year thereafter numerous ascents have been made. In recent years as many as 20 to 30 parties have climbed the peak each summer. Not a few women and children are included among those who have scaled the Grand Teton.

Repeated efforts were made to achieve the summit of the Grand Teton by routes other than the traditional one, and in 1929 one of these resulted in a successful ascent of the east ridge by Kenneth A. Henderson and Robert L. M. Underhill. In 1931 no less than three additional routes were discovered: the southwest ridge was climbed by Glenn Exum; the southeast ridge by Underhill, Phil Smith, and Frank Truslow; and the north face by Underhill and F. M. Fryxell. Thus five wholly distinct routes have been employed on this mountain, though only the traditional route and possibly the southwest ridge can be recommended to any except most expert alpinists.

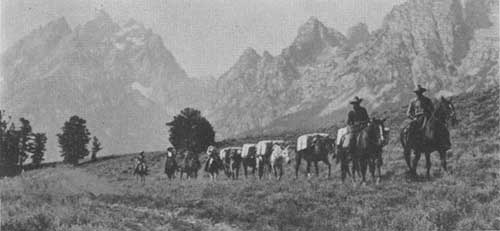

Pack-train trips in Grand Teton Park. Copyright, Crandall.

Within the last decade other peaks in the range have come in for more and more attention. This they richly deserve, since from both a scenic and mountaineering standpoint many of them are worthy peers of the Grand Teton itself. Mount Moran, Mount Owen, Teewinot, Nez Perce, and the Middle Teton comprise a mountain assemblage which, for nobility of form and grandeur, would be difficult to equal anywhere.

So far as known Buck Mountain, most southerly of the "Matterhorn peaks", was the first major peak in the range to be scaled, the ascent being made early in 1898 by the topographical party of T. M. Bannon. Thereafter no important ascents were made until 1919, when LeRoy Jeffers scaled the lower summit of Mount Moran. The main summit of this peak was first climbed in 1922 by L. H. Hardy, Ben C. Rich, and Bennet McNulty. In 1923 A. R. Ellingwood climbed both the Middle and South Tetons on the same day, on the South Teton being accompanied by Eleanor Davis. In 1928 Mount Wister was climbed by Phil Smith and Oliver Zierlein; in 1929 Teewinot and Mount St. John by Fryxell and Smith; in 1930 Nez Perce by Fryxell and Smith; and Mount Owen by Underhill, Henderson, Fryxell, and Smith. With the ascent of Mount Owen the conquest of the major peaks, begun so many years before, was at length completed.

In the meantime the minor peaks were by no means neglected, the first ascents being made principally since 1929 by the climbers whose names have already been mentioned. As in the case of the Grand Teton, a variety of routes have been worked out on almost all of the major and minor peaks. Between 1929 and 1931 the important summits of the range were equipped with standard Government register tubes and register books, in which climbers may enter records of their ascents. The story of the conquest of the Tetons is told in a book entitled "The Teton Peaks and Their Ascents." (See Bibliography.)

SUGGESTIONS TO CLIMBERS

Since 1931 authorized guide service has been available in the park. In view of the difficulties one encounters on the Teton peaks and the hazards they present, prospective climbers—especially if inexperienced—are urged to make use of the guide service. If venturing out unguided, climbers should under all circumstances consult rangers or guides for full information relative to routes and equipment. Failure to heed this caution has, in the past, led to accidents and even fatalities. Climbing parties are required, under all circumstances, to report at either park headquarters or Jenny Lake Ranger Station before and after each expedition, whether guided or unguided.

The climbing season varies with the amount of snow in the range and the character of the weather, but ordinarily it extends from the middle of June to the end of September, being at its best during July, August, and early September. In most cases it is advisable to allow 2 days for an ascent of the Grand Teton, Mount Owen, or Mount Moran, and 1 or 2 days for all other peaks depending upon the experience of the climber and the time at his disposal. Jenny Lake Camp Ground is the logical outfitting point for most expeditions; it is close to the peaks and the sources of supply as well. For most ascents the usual alpine equipment—ice axes, rope, and hobbed boots or climbing shoes—is essential. In the case of guided parties arrangements for renting equipment may be made with the guides.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936/grte/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010