|

GRAND TETON

A Tale of Dough Gods, Bear Grease, Cantaloupe, and Sucker Oil: Marymere/Pinetree/Mae-Lou/AMK Ranch |

|

SARGENT ERA

Machias, Maine, incorporated in 1784 and the seat of Washington County, was a particularly busy lumbering and seafaring town in the last half of the 1800s (Fig. 1) (Drisko, 1904). Early in this period, several community families were destined for involvement with Wyoming's very remote and little known Jackson Hole region. The Ignatius Sargent family was prominent in Machias where Ignatius had served as Treasurer of Washington County for about 33 years. Also, he was a partner in the Sargent, Stone and Company Foundry and Machine Shops (Fig. 2) and one of the owners and general manager of the Machias Water, Power and Mill Company (Colby, 1881; Drisko, 1904; E. W. Sargent, 1923). In addition, he was involved extensively in ship building and maritime shipping with sole or partnership interests in 35 ships (National Archives Project, 1942).

|

| Fig. 1. Machias waterfront along Machias River in 1880s. (Hartley Crane Coll., Machias, ME.) |

|

| Fig. 2. Machias in 1880s with Sargent, Stone and Co. Foundry and Machine Shops along upper left riverbank. (Hartley Crane Coll., Machias, ME.) |

The Sargent name was well-known in New England. Ignatius was a third generation descendant of Epes Sargent of Salem, Massachusetts. Another famous Epes Sargent descendant was John Singer Sargent, the American painter. However, Ignatius and John Singer were descendants of different wives of Epes Sargent. Ignatius descended from Epes Sargent's second wife, Catherine Winthrop Sargent, and John Singer was a fifth generation descendant of Epes' first wife, Esther Maccarty (E. W. Sargent, 1923). Ignatius and his wife, Emeline, had a son, Henry C., who was 17 years old in 1860 (U.S. Census, 1860).

Concurrently, the family of William H. and Elizabeth Hemenway of Boston, Massachusetts (State of MA, 1861), had taken up residency in Machias to facilitate William's real estate and development enterprises (H. Crane, 1985). Among his major businesses was the leasing and promoting of the Machias Water, Power and Mill Company (Drisko, 1904). In 1860, his daughter, Alice, was 16 years of age (U.S. Census, 1860).

Henry Sargent and Alice Hemenway of the aforementioned prominent families attended the Washington Academy (a private school in East Machias, a town 4 miles from Machias) between 1853 and 1863 (Pierce, No date). Consequently, their marriage on July 18, 1861 (State of MA, 1861), was not an unlikely event. What was unusual was the birth of a son, John Dudley Sargent, on December 16, 1861. Henry C. Sargent was listed as his father and Alice as his mother on the birth certificate (State of ME, 1861). Two logical explanations of this early birth are (1) Henry and Alice were engaged in a premarital affair some 4 or 5 months prior to their July 18 marriage; or (2) Henry was not the father of John Dudley. Many years later in his final will and testament (J. Sargent, 1899), John Dudley related how his grandmother Hemenway on one occasion introduced a "tall, dark, slender" visitor at her house as a Mr. E. Jerome Talbot. During the same visit, John Dudley's mother, Alice, privately introduced Mr. Talbot to John as his real father.

As a matter of record, an Edward Jerome Talbot, son of Samuel H. and Mary Talbot of East Machias (U.S. Census, 1860a) also attended the Washington Academy sometime between 1843 and 1853 (Pierce, No date). The U.S. 1860 Census of East Machias, Maine, listed Mr. Talbot, age 21, as living with his parents in East Machias where he was employed as a clerk. E. Jerome Talbot married Fannie Hayden on December 3, 1863 (Machias Union, 1863). In line with the Talbot family interests in maritime shipping, Edward pursued a seafaring career. Unfortunately, this professional pursuit was short-lived with Edward's untimely death at sea on January 8, 1866 (Machias Union, 1866). While only circumstantial, the aggregate of those circumstances appear to substantiate that Henry Clay Sargent was not John Dudley's real father but Edward Jerome Talbot may have been.

Immediately following their marriage, Alice and Henry moved in with her father, William C. Hemenway, on the corner of Court Street and Broadway in Machias. In accounts written by John in the margins of the book, Some Fruits of Solitude, prior to his suicide (V. Lawrence, No date) and statements written in his will (J. Sargent, 1899), John recalled living in grandfather W. H. Hemenway's house until 1872. During this period, Henry C. Sargent, his legal father, appears to have been an irregular member of the Hemenway household. Henry volunteered for service in the Civil War on May 21, 1861, as a Private in Company C of the Sixth Regiment Maine Infantry. He reported for active duty on July 15, 1861, when he was 18 years old and received a disability discharge on October 25, 1861, supposedly for a hernia problem (ME Infantry, 1864; Titus, 1985). In 1866, he traveled alone to California via the Isthmus of Panama (Fig. 3).

|

| Fig. 3. Henry Clay Sargent. (Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL.) |

Sometime in 1872, illness of John's grandfather and/or his mother required his moving in with the Ignatius Sargent family on Water Street (Fig. 4). His grandfather Hemenway died on November 5, 1874 (Washington Co., 1874), and his mother, Alice, died in Boston on December 1 of the same year (State of MA, 1874). John appears to have lived in the Ignatius household until 1879-80 (J. Sargent, 1913). During those years, Ignatius and Henry likely supported him.

|

| Fig. 4. Sargent family home, Machias. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Laramie, WY.) |

It is difficult to assess the impact on John during his first 19 years of having a very weak or disrupted family life and of knowing that he was probably an illegitimate child. Some measure of his early disillusionment is evident in 1875 when he met with a Mr. Harding in his recently deceased grandfather Hemenway's office. In this meeting, John said, "bottom dropped out of everything" (V. Lawrence, No date). With no further elaboration, one can only speculate on the causes for this feeling. Likely his depression over the loss of his mother and grandfather was amplified with his grandmother Hemenway moving out of Machias to Portland and thus the complete loss of the last vestige of his early life in the Hemenway house. The fact that John was not going to receive anything from his grandfather's estate may also have depressed him (Washington Co., 1888).

During the period between late 1879-80 and 1885, John Sargent's activities are poorly documented. Again from his notations in the margin of the book, Some Fruits of Solitude (V. Lawrence, No date), it seems that John traveled west to Cheyenne, Wyoming, Denver and Leadville, Colorado, in March 1880. He worked there until 1885 as a ranch hand punching cattle and as a stage driver (J. Sargent, 1906). Through all of this, he probably returned one or more times to Machias in the course of his courtship of Adelaide Crane, daughter of Leander and Edwina Crane. The Cranes were a prominent Machias lumbering and maritime shipping family. In 1885, John's residence was listed as Ft. Fetterman, Wyoming Territory (Machias Union, 1885).

John Sargent's courtship of Adelaide Crane culminated in their marriage on February 22, 1885 (State of ME, 1885), in the bride's parents' home in Machias (Machias Union, 1885). The Crane family was very much opposed to this marriage (Titus, 1977a). The terse two sentence announcement in the newspaper, after what appears to have been a private wedding in the family home, serves to substantiate that antagonism.

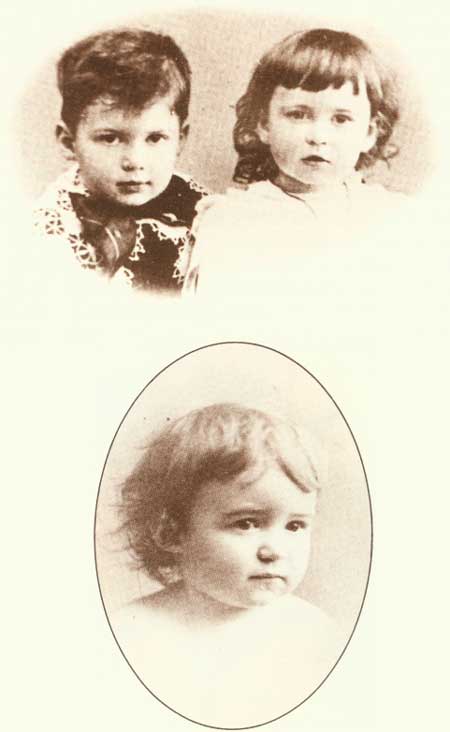

Following the wedding, there is a gap in the activity record for John and his bride. According to the Machias U.S. 1900 Census, John and Adelaide's first child, Charles Hemenway, was born in Connecticut in December 1885 (Fig. 6). This was substantiated in part by R. Wright (No date) who lived with Charles in the home of Leander Crane as a young girl. Furthermore, Verba Lawrence listed the birth place of Charles as New Haven, Connecticut (V. Lawrence, No date). The New Haven location was apparently temporary with Adelaide living with her parents at that time. Leander Crane was listed in the New Haven City Directory only for the years 1886 and 1887 (Fig. 5) (Clendinning, 1985). He was then Treasurer of the Crane and Franklin Stove Company. Leander returned to Machias in 1887 (R. Wright, No date).

|

| Fig. 5. Leander H. Crane. (Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL.) |

Between 1885 and 1890, John's travels to the West are sketchy. As mentioned before, it seems that Adelaide moved in with her parents when they moved to New Haven; while it appears John traveled to the West to both search for a suitable place to settle and simultaneously increase his financial resources. Two former residents of Jackson Hole, Esther Allan (Allan, 1973) and Elizabeth Hayden who interviewed Mary Sargent in 1955 (Hayden, 1955), and a written note by John (V. Lawrence, No date) stated John entered Jackson Hole in 1886. This information is contradictory and confusing at best, since John related that he worked for 2 years on the railroad, likely from 1885 to August 1887 (J. Sargent, 1906). If he did visit Jackson Hole in 1886, it was for a very brief period.

According to a note in John's homestead correspondence, he and his family left Cheyenne on August 1, 1887, enroute to his "estate" (J. Sargent, 1906; 1913). The assumption here is that this reference is to the Jackson Hole property. Sargent never claimed he settled in Jackson Hole at this time. Again, it must have been a short visit. However, prior to this visit, Adelaide and Charles had come to Cheyenne where a second child, Mary, was born sometime prior to August 1, 1887 (Fig. 6). This period for her birth is based on information from the District Court in Evanston, Wyoming (Uinta Co., 1900), and the U.S. 1910 Census of Uinta County. Also, John stated he traveled from Cheyenne to his "estate" with two small babies on August 1, 1887 (J. Sargent, 1906). Unfortunately, birth information was not compiled by Wyoming in the 1880s; but Mary Sargent told Elizabeth Hayden (Hayden, 1955) that she was born in Cheyenne.

Sargent's third child, Martha, was born on September 19, 1888, in Machias (Fig. 6) (Church of the Ascension, 1890). Based on known future travel patterns of the Sargents, one can assume that the entire family or part of the family made irregular or seasonal (winter) trips back to Machias before 1890. Since such trips were costly, one can speculate that the Henry C. Sargent family and/or the Crane family underwrote those trips.

|

| Fig. 6. Charles, Mary and Martha Sargent (l—r). (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum) (Charles & Mary); Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL (Martha).) |

Reference has frequently been made by numerous writers about John's college education at such places as Harvard, Yale and Columbia Universities before 1890. Replies to our inquiries of each of those institutions indicated there were no records of a John Dudley Sargent ever having graduated from or even having attended those schools (Columbia Univ., 1985; Harvard Univ. Lib., 1985; Yale Univ. Lib., 1985). It is possible he may have been a student for a brief period of time, since records of students attending but not graduating were poorly or not kept for the late 1800s. Considering John's activities before and after he was 19, there was no possibility for him to have attended any of those schools for any length of time, much less graduate.

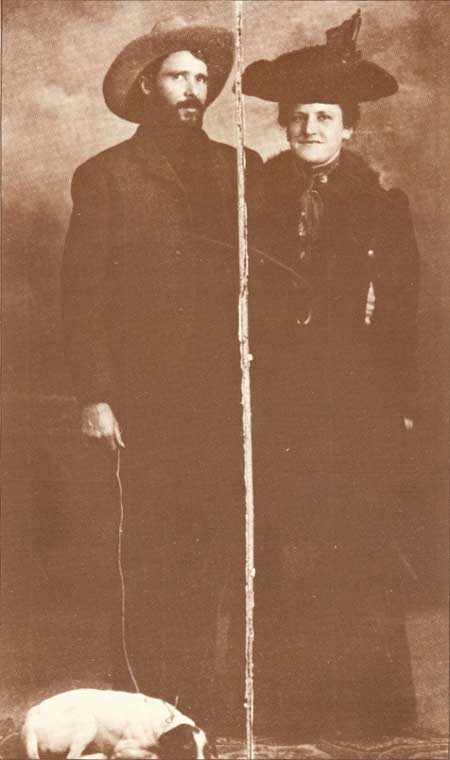

In New York in 1889-90, an event that would profoundly affect Sargent was unfolding. Robert Ray Hamilton clandestinely married Evangeline L. Steele (aliases Brill and Mann) in Paterson, New Jersey, on January 7, 1889 (N.Y. Times, 1889f). Hamilton was a fourth generation descendant of Alexander Hamilton. He was 37 years old, independently wealthy, a lawyer and member of the New York Bar and a member of the New York Legislature. He is described by the New York Times as being 5 feet 10 inches in height, slender, dark complected and wearing a light mustache. His eyes and hair were black and he dressed well. Hamilton was a handsome man with clean-cut features and keen eyes (N.Y. Times, 1889; 1889a). Eva Steele was an attractive woman with an unsavory background which caused Robert's friends and relatives to ostracize him (N.Y Times, 1889a). By May 1889, this situation had become so unbearable that Hamilton decided to leave New York and relocate in California. However, once in California, the climate was disagreeable and he and his wife moved to Atlantic City in August 1889. In Atlantic City, a heated family quarrel erupted into an attempted stabbing of Robert and a near fatal stabbing of their child's nurse by Mrs. Hamilton (N.Y Times, 1889b). In the ensuing investigation by police and friends, it was discovered that Robert was the victim of a conspiracy by Eva; her common-law husband, Josh Mann; and his mother, Mrs. Swinton. The conspiracy involved the use of a newborn baby which the conspirators obtained for Eva to convince Hamilton the child was his (N.Y Times, 1889d).

In the course of the marriage, Eva accumulated money and property from Hamilton and was planning to convert much of his jewelry and silver plate into currency. Also, she was living in a very high style with elegant amenities (N.Y Times, 1889a; 1889b; 1889c; 1889d and 1889e). Once the stabbing affair inquiry exposed these events, the conspirators' trial in New Jersey and subsequent divorce proceedings in Elmira, New York, consumed Hamilton's time until March 11, 1890, when he left Elmira for New York City (N.Y Times, 1890).

In May 1890, Robert left New York City on a hunting trip to the West (N.Y Times, 1891). At about the time he may have arrived in the West, it is speculated that Sargent was making preparations to build or was already in Jackson Hole building. Contrary to many statements that Sargent's family arrived in Jackson Hole in October 1890, Sargent said (Uinta Co., 1900) that he brought his family to Jackson Hole in July 1890. He further said his wife was at their ranch in August 1890 (N.Y Times, 1890a).

Exactly where and when Robert Ray Hamilton met Sargent is unknown. Sargent may have known his father, General Schuyler Hamilton (N.Y Times, 1913). But Sargent stated, "we have known him (Robert) but a short time" in a letter he wrote to Robert's brother in 1890 (N.Y Times, 1890a). As mentioned before, Robert came to the West after May 1890; and the New York newspaper, The Sun (1891), indicated Hamilton only resided in Jackson Hole a matter of weeks before his death in September 1890.

During their brief acquaintance, a partnership apparently was agreed upon. Robert was so impressed with Sargent's homestead location that he had decided to send for his personal belongings and make it his future home (N.Y Times, 1891). It seems likely there was some mutual sharing of expenses for the planned 10-room cabin. Beyond that, the business end of the partnership probably was a proposed dude ranch-outfitting business to exploit the area's hunting and fishing resources. With Sargent's experience in the West since 1880 and Hamilton's professional, political and social connections, such a collaborative venture could have been mutually beneficial.

It is impossible to determine what fiscal investments were made by each partner. Despite his heavy financial losses to the marital conspirators (N.Y Times, 1889g), Hamilton appeared to have ample financial resources remaining, according to his will of 1890 (N.Y Times, 1890c). At the same time, Sargent must have had reasonable fiscal resources considering the furnishings placed in the cabin, the costs of shipping those items, plus the traveling and interim living expenses for his family. Since there were no legal questions raised by the Hamilton family concerning homestead proprietary interests after Robert's death, the question of the partnership investment relationship remains unanswered.

Financial matters aside, construction of the 10-room Sargent-Hamilton cabin (Fig. 7) must have started very early in the Summer 1890. Swedish log workers from Idaho were hired to build the cabin. The logs were hewed flat on the inside surfaces and the dovetail coped end joints were sometimes supplemented with wooden pegs. Whip-sawed 2-inch planks were used for flooring and whip-sawed boards were cut for window, door casements and ceilings (Fig. 8) (W. Lawrence, 1978).

|

| Fig. 7. John D. Sargent's cabin, 1891. (Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL.) |

|

| Fig. 8. Whip - saw platform and sawyers. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

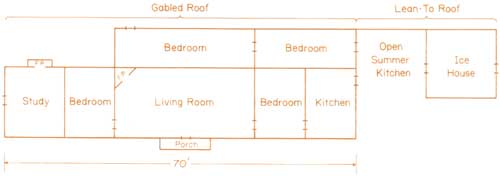

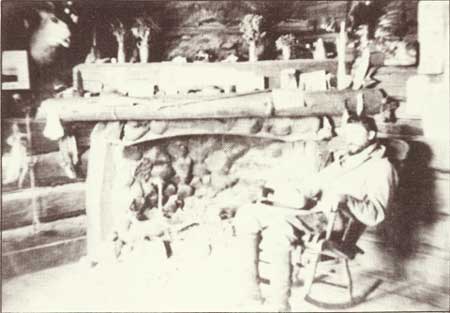

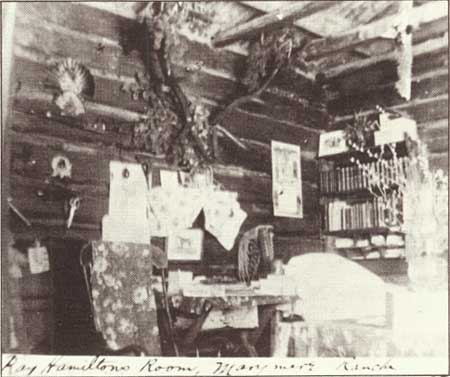

A general floor plan of the Sargent cabin, developed from recollections of W. Lawrence (1980), old photographs and information from Spence (1906), is presented in Fig. 9. The small bedrooms at the back of the house were dark and only about 5-foot wide. Their exact number and size were not verifiable. The open summer kitchen contained a stove and table. During winter and inclement weather, a large canvas covered the opening to that area. Access to the room at the north end of the cabin was limited to the one outside door. In a photograph dated 1891, one year after Hamilton's death, that room was labeled "Hamilton's Room" (Figs. 10; 11; 12; 13) (Titus, 1982).

|

| Fig. 9. Floor plan of John Sargent's cabin. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Univ. of WY, Laramie.) |

|

| Fig. 10. Northwest corner of Sargent's cabin around 1905. (Nat'l Archives & Record Serv. Evanston, WY, Homestead Final Certificate 1024 and Misc. Letter 353992. Gen. Br., Civil Archives Div., Wash., D.C.) |

|

| Fig. 11. John Sargent by living room fireplace. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY(Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 12. John Sargent's living room with furnishings, 1907. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 13. Hamilton's room (study) at north of Sargent's cabin, 1891. (Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL.) |

During construction, Robert invited two of his friends out to hunt in September: Cassimir De R. Moore and Gilbert M. Speir (Sun, 1891). Unfortunately, Hamilton drowned fording the Snake River below the outlet from Jackson Lake on August 23, 1890, while returning alone from an antelope hunt. Three sources of information on his death seem to be the most reliable: John Sargent's letter to Hamilton's brother, Schuyler; Cassimir De R. Moore's letter to Schuyler; and Dr. J. O. Green's account of finding the body (N.Y Times, 1890a; 1890b).

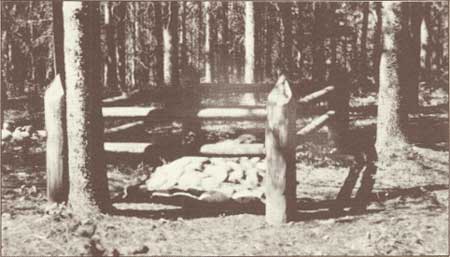

Hamilton attempted to ford the river in the dark and crossed in the wrong area. At the time of the accident, Sargent was at Kamtuck, Idaho, getting supplies and mail; and he did not return until August 27. Upon his return, Sargent asked for local assistance from several Jackson Hole residents to search for Robert who was several days overdue from his hunt. Hamilton's body was found on September 2. His horse had been able to swim ashore despite a turned saddle, while Hamilton was found with his spurs tangled in the aquatic plants of the river channel (N.Y Times, 1890a; 1890b). The searchers had agreed to light a signal fire, if and when his body was found. On September 2, such a signal fire was constructed on the low mountain now named Signal Mountain (Leek, 1923). Hamilton was buried directly west of the Sargent cabin in a site which is now flooded by Jackson Lake. Several years after his death, the body was removed from that gravesite and sent back East for internment in the Hamilton plot (W. Lawrence, 1981; Jackson Hole Guide, 1958).

Because of the remoteness of the area, communications were not only slow, but usually lacked sufficient details. As late as June 1891, Sargent traveled to New York to testify that indeed the body recovered from the Snake River was Robert Ray Hamilton (N.Y Times, 1891a; 1891b).

Rumors of foul play persisted supporting such an event (N.Y Times, 1891c). Those unfounded rumors ultimately suggested Sargent was involved in the treachery and killed Hamilton to gain sole possession of the ranch (Kongslie, 1891). While on a hunting trip sometime between 1896 and 1900, Dr. John Mitchell wrote in his diary, "All Jackson's Hole, a community of scalawags, renegades, discharged soldiers and, as Capt. Anderson, calls them, predestined stinkers, unite in the belief that Sargent killed H" (Jackson Hole Guide, 1965). In 1913, after John D. Sargent's death, his second wife, Edith, wrote a letter to the New York Times editor to exonerate John, stating that the coroner's jury decided that Hamilton's death was accidental and that John was incapable of committing murder (N.Y Times, 1913).

The Winter 1890-91 was a most trying time for the Sargent family. The cumulative impact of establishing and constructing a new homestead in an environment with a severe winter climate, plus all of the events associated with Hamilton's death, would test the mental state of most individuals.

Final completion of the 10-room cabin probably carried over into 1891. Other log homestead structures built included a 12-foot by 12-foot barn which had a gable roof and a haymow above the stable and harness storage area. Several corrals were associated with the barn. The barn was located on the north side of the clearing which was used by Alfred Berol for trap shooting from the 1940s to the 1960s. Behind the main cabin (to the northeast) were four other log structures: an outhouse, an 8-foot by 8-foot chicken house, a 12-foot by 12-foot woodshed and a 16-foot by 20-foot boathouse (Woods, 1904). The latter structure which was packed into Jackson Lake from Marysville, Idaho (Allan, 1973). This boat could be rowed but it also was outfitted with a mast for sailing. This is a logical piece of equipment considering Sargent's background in the seaport town of Machias. W. Lawrence (1978) reported seeing remains of this boat in the crumbling boathouse with the mast step still in place in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Sargent's homestead was located on an open ridge of a short peninsula which extended in a northerly direction into Jackson Lake (Fig. 14). This location provided an exhilarating view across Jackson Lake of the east slopes of the Grand Teton Mountains (Fig. 15). Most of the scattered trees were under 10-foot tall and represented new forest growth established following the fires of 1879 which burned over large portions of Jackson Hole (Gruell, 1980). There were no springs for water on the ridge; water was hauled from Jackson Lake. One steep water haul road led directly west from the cabin to the lake. When this road was wet or icy, a more gentle but longer road to the north end of the peninsula was used. Water was hauled in wooden barrels having canvas covers. It was then loaded on a wooden sledge pulled by a Shorthorn bull which Sargent used as a utility work animal (W. Lawrence, 1978).

|

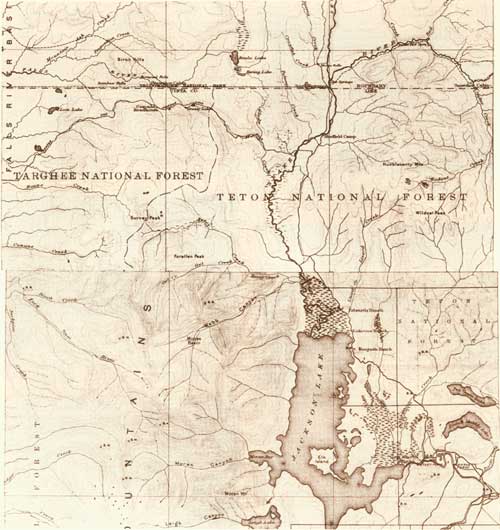

| Fig. 14. USGS topographic maps, 1901 (bottom) and 1911 (top) Editions. (U.S. Geological Survey. Topographic maps: Grand Teton 1901; Shoshone 1911.) |

|

| Fig. 15. Webb expedition (Purdy, 1896) in front of Sargent's cabin, Sept. 1896. (Haynes Foundation Coll., F. J. Haynes photograph H 3636. MT Historical Soc., Helena, MT.) |

With respect to a transportation system serving the Sargent-Hamilton homestead, a major Indian-fur trapper trail down the east side of Jackson Lake passed just to the west of the homestead. This trail led to the Conant Pass Trail which went over the north end of the Teton Mountains for travel into Idaho. The Sargent family frequently used this trail to move in and out of Jackson Hole. The Yellowstone Military Road was the main route connecting Jackson Hole with Yellowstone National Park and Montana. This road passed east of the Sargent homestead (Fig. 14). A short secondary loop which passed right by the Sargent Cabin was used mostly by travelers as an access to campsites south of the ranch buildings (W. Lawrence, 1978).

There is no well-documented record of pets and livestock on the Sargent homestead. Several dogs and a cat named "Tom Tough" were shown in various photos of the ranch. Martha Sargent, daughter of John, talked of loving her two dogs, Joke and Jolly (Titus, 1982). The J. V. Allens frequently commented that Sargent was "very, very good to animals" (Allen, 1981). Also, John had great pride in his Shorthorn bull which he raised and had trained to pack, to be ridden and to pull equipment (Fig. 16) (J. Sargent, 1906a; W. Lawrence, 1978).

|

| Fig. 16. Sargent's shorthorn bull and northeast corner of Sargent's cabin, 1905. (Nat'l Archives & Record Serv. Evanston, WY, Homestead Final Certificate 1024 and Misc. Letter 353992. Gen. Br., Civil Archives Div., Wash., D.C.) |

In addition, Sargent had at least one horse. As a young boy, Marion Allen (1981) observed Sargent going for his mail, "Usually he would be walking and his saddle horse would be following him and a pack horse following the saddle horse, making quite a parade." Also, Ben D. Sheffield Jr. knew the Sargent family and remembered their pinto horse called "Nymph" and John Sargent's "cow" that he packed on trips to Moran (Fig. 17) (Sheffield, 1985).

|

| Fig. 17. Moran, prior to 1910. (Benjamin David Sheffield Coll., Acc. No. 7573, Neg. No. 21227. Archives Div., Amer. Heritage Center, Univ. of WY, Laramie.) |

Sargent, writing to the U.S. Land Office in Evanston, Wyoming, claimed he grazed six milk cows six seasons prior to 1897 on his homestead and milked the cows regularly for the benefit of his wife and children. It seems the usual over-winter animal herd consisted of 1 cow, 1 bull and 1 horse (J. Sargent, 1 906a). The severe winters and the family's periodic absences during the winter restricted the number of animals that could be maintained. Evidence suggests that he might have wintered some of his stock in Idaho (J. Sargent, 1906a). Also, Sargent might have had a small herd of cattle. Noble Gregory first established his homestead near the Buffalo Fork River and initially acquired some of his cattle from Sargent (Jackson's Hole Courier, 1952). In the Wyoming Stock Growers Association records, J. D. Sargent of Moran in 1905 was assessed for 31 head of cattle. Sargent was not mentioned for any other year in their records (WY Stock Growers Assoc., 1905). Forest Ranger Rudolph Rosencrans on July 2, 1907, wrote in his diary that he "made out hay application for J. D. Sargent" and on August 10, 1907, "from Lake went to Sargent's to see about signing a special permit application" (Rosencrans, 1907).

The name "Marymere" for Sargent's homestead ranch has been recorded and spelled in the literature in many different ways. In the beginning, Sargent used that name to refer to what is now Jackson Lake (N.Y Times, 1890a) rather than the ranch itself. That changed over time (J. Sargent, 1899; Kongslie, 1891). While numerous versions exist of the spelling and writing of the name, "Marymere" seems to be the version utilized by Sargent.

After Hamilton's death, Sargent continued the efforts to operate the Marymere Ranch as a dude-hunting ranch. One such party, wealthy Cleveland merchant Ralph Worthington and three nephews of Andrew Carnegie, stayed on the ranch for a few days (N.Y Times, 1891c). The Sargents apparently provided their guests with a sumptuous fare for that isolated area. Kongslie (1891) tells of having wine and expensive cigars during one overnight stay on their way to Yellowstone. Mary Sargent said her father also served champagne to his guests. In those early years on the ranch, one to two girls from Idaho were hired employees (Hayden, 1955; J. Sargent, 1892). While Sargent and Adelaide had some initial financial resources, one might logically speculate that their costs of operation were greatly exceeding their earned income.

Besides the potential of fiscal stress, winter living on the Marymere had to be very trying. Five to 6 feet of snow accumulated seasonally on the ground or in one storm. Temperatures frequently plunged to -40°F and even -60°F. Valley fog rolled up and down the northerly portions of Jackson Hole until Jackson Lake froze over. W. Lawrence, who lived next to Jackson Lake, mentioned they may not see the sun for about 2 months from late November through January. The heavy wet snows usually occurred from February through April. Overall, these conditions made it (1) difficult to over-winter livestock; (2) difficult to travel except by snowshoe and skis; (3) difficult to receive or send letters and other communications to business contacts, friends and family; and (4) difficult to avoid mental depression and irritability ("cabin fever") from prolonged isolation and prolonged confinement in small homestead cabins.

Sargent and his family spent a number of winters outside Jackson Hole. He described his family's November 1892 horseback travel over Conant Pass into Idaho. His account, found by Robert Barton in the belongings of his father, J. Oland, John's son-in-law, is shared with the reader (Titus, 1977; J. Sargent, 1892)*:

"Best Camping Experience

We had been living on the ranch at Jackson Lake several years when it was decided to spend a winter in town.

The beautiful Autumn had been perfect way into October and we were all at the ranch after the last colors along the lake shore had faded, and the last of the rustling Aspins had shed their leaves in front of our Cabin.

There was five of us to move across the Tetons before we could get to a Railway; three children from four to eight years old, their mother and the writer. Late in October three of us, the eldest child, his mother and the writer, started out on saddle horses, with a camp outfit consisting of a 12 ft. Indian Lodge, 6 pair 8 lb. Provo Utah blankets, a weeks ration of Elk meat, flour, sugar, dried fruit, baking powder, salt, pepper, bacon and matches, leaving the other two children with the hired girl at the ranch. Of course, our camp outfit was on a pack horse. Our route was the seldom traveled Conant Trail, which crosses the Teton Mountains six miles north of the head of Jackson Lake, but about fifteen miles as you follow the trail.

We traveled single file, the pack horse being used to it and no bother. After fording the Snake River at the Old Indian Crossing, three miles above the lake our trail wound about in the pines and lower Cottonwoods till we got up to the Berry Creek Valley, which is a small narrow valley running off East from the East end of Conant Pass with fine Mountain water in Berry Creek and its spring branches.

On one of these, at a spring branch, in a little grassy park where I had my old lodge poles stacked away, we camped the first night, clear and cold, but entirely pleasant. We slept, cooked and ate in the lodge. Next morning we packed up and by noon were on top of the Conant Pass enjoying a panoramic view of half the state of Idaho.

In another hour we were down through the dense fir and pine timber of the west slopes of Tetons and riding out over lovely Mountain Parks and through occasional groves of Aspins, pines and big fur trees.

About fifteen miles below the Mountains, just at sundown, in a grassy meadow, we came to a Settler from an Idaho Hamlet, our destination before going to Railway. This man was hauling hay from this wild meadow, which he had been cutting, all the way to his home, thirty miles nearer to the Railway, and he loaded the boy and his mother on top of the hay load the next morning and I returned with my camp outfit and horses across the Conant Pass that same day to the Jackson Lake side again, driving the horses before me in the narrow trail single file at a trot whenever the ground would permit. I was home by sundown.

The next day I started out the eldest girl with the hired girl, on a wagon by way of Falls River Pass, which passes around the head of the Teton Range just inside the southwest corner of the Yellowstone Park. It is passable for wagons but not a smooth road. Then I was all alone with my four year old daughter Martha at the ranch, and a big snow storm closing down on the Lake and Tetons. In the midst of it Colonel Anderson, U.S.A. and Lieut. Devoll, U.S.A., arrived with a Government Pack outfit from a tour of the east side of the Yellowstone Park. We all enjoyed the comfort of the big ranch fireplace that evening while the snow steadily fell outside. After the Colonel's party pulled out for Fort Yellowstone, one hundred miles north over the old Sheridan Trail, no roads in those days up to the Park, I began to get ready for our last trip over Conant Pass, to join the others in Idaho, and then go into Salt Lake City for the winter.

The morning I packed up the five pack horses with my most valuable property there was a foot of snow on the ground at my ranch and it was still snowing. I knew that meant three or more feet on top of Conant Pass. Martha, the "baby" was going across in midwinter weather practically—and her mother and brother had crossed in beautiful Indian Summer weather less that a week earlier! It can do that in the Teton Mountains sometimes.

It was noon before I'd packed the last horse, turned it loose in the bunch and while they all stood huddled together by the front door of the Cabin with their tails to the snow storm and the canvas covers of their packs changing rapidly from dirty white to snowwhite. I went in the cabin and dressed Martha for the ride. A cloak of Provo blanket to her heels, german socks and overshooes, a warm hood and wollen mittens and she was apparently very fat and all ready for any thing outside.

Tossing her up into an extra stock saddle of mine on Old Roan, a thoroughly safe old time pony, I gave Martha her bridle rains, told her to follow up the procession; drove the bunch of pack horses into the trail, got in the lead then myself on my best horse and Martha followed in the rear with all the pack horses single file between us. On the Big meadow, three miles north of my ranch, just before we were to ford the Snake River, I discovered I'd forgotten my keys. I stopped the pack train, told Martha the trouble, unpacked the dozen or more pair of Utah blankets from Babe, tumbled them into the snow on top of the lodge, quickly slipped Martha out of her outside wraps as she set in the saddle, then tossed her in the middle of the blankets, wrapped the lodge over all, after shaking the dry snow off her wraps and storing them under the folds of the lodge, mounted my horse, sang out 'Go to sleep Martha' and lit out for my ranch. With my keys safe in my pocket I returned to the meadow forty minutes later to find a big mound of dry soft snow and Martha sound asleep in the middle of it.

Quickly wrrapping her and mounting the girl on Old Roan I soon had Babe repacked with the bedding and lodge and we were on the trail once more. It never ceased snowing a moment and there was eighteen inches on the meadow as we crossed it to the ford of the River.

Soon after crossing the river we had to camp for it was near dark. I chose an old spot of Beaver Dicks where I knew he had his lodge poles cached. I soon had them set up, the lodge nicely stretched over them, blankets and cooking things inside, a fire in the centre of the lodge, then I removed Martha's outside gear as before as she set in the saddle and carried her in to the brightness and warmth of the lodge. Leaving her, sitting in some blankets by the lodge fire, I went outside, unpacked the remaining loads, staked out in a bit of open Park the bell mare, and turned the rest loose to graze through the night. With my axe I cut up fire wood for night and morning, piled it inside under the edge of the lodge, then I began our supper preparations.

Opening a 50 lb. sack of flour, I mixed two teaspoons full of baking powder with about a quart of the top flour, then fried some bacon in frying pan. Made a "Dough God" with a little water in the top of the flour sack, placed the "Dough God" in the frying pan on top of the slices of cooked bacon, cooked it a while over the coals—then I flopped over the "Dough God"—cooked that side as I had the top, took it out of the frying pan, stood it up against a stick facing the fire where it would bake slowly, turning it about occasionally, while I heated up some canned corn in the frying pan, boiled an Elk steak on coals, using a wire toaster, and made tea.

Opening a can of Eagle milk I fixed a big tin cup full of it with hot water for Martha and getting out the plate, knife and fork and spoon for her we set to it.

Our bed was made down beside the fire and as we turned in I could see a star or two through the peak of the lodge. Two minutes after saying her prayers Martha was sound asleep.

We got a late start next forenoon. Wasn't snowing, but threatening to, and at it so thick and hard again by the time we reached the top of the Pass could not see 30 yards.

Quarter of a mile below the top Martha dropped a mitten and I had to wallow down the Mountain side back after it through three feet of snow. It was a black mitten so easily recovered on all that snow! We were obliged to camp that night on the summit in three feet of snow. Under the north side of the pass I unpacked in the dark, Martha sitting still on her pony meanwhile. I set no lodge that night! We slept in the blankets with a fir tree and sky for our roof.

It cleared off bitterly cold towards morning, up there at 9000 ft. altitude in November. When I had breakfast ready it was quite warm and pleasant, the sun peeping at us finely over the crest of the Pass above our heads.

By Midafternoon we were down out of the snow and traveling through the pretty open parks and groves of the Idaho side in Indian Summer weather again. Just then Babe, the pony that carried half the blankets, began to drop behind and bothered Martha. I told Martha to let her alone and she'd follow us.

When we camped for the night Babe did not come in. Leaving Martha alone in the camp I took the back trail and found Babe lying down by the trail with her bulky pack turned under. She simply could not get on her feet. Unpacking and repacking her I got her into camp at midnight.

Next day at noon we rode out on the Idaho prairies and ten miles farther we came to the first cabin in a small farm at Conant Creek crossing and a good wagon road on to the hamlet where the others awaited our arrival."

*This is from a typed copy of the original handwritten account by John D. Sargent. It is not known who made the copy or how accurately Sargent's grammar and spelling were reproduced.

In his affidavit to Wesley King, U.S. Land Commissioner, Sargent swore he and his family left Marymere in November 1892 because of his "wife's sickness," without any clarification by him as to the nature of the illness (J. Sargent, 1904). Interestingly enough, Sargent did not mention in the journal anything about his wife being ill during the foregoing trip. Nor did he say anything about her being pregnant. Nevertheless, on November 14, 1892, the fourth Sargent child, Catherine, was officially recorded in the State of Utah as being born to Adelaide and John in Salt Lake City (Salt Lake City-County, 1892; Church of the Ascension, 1897) 12-14 days after a 2-day horseback trip over Conant Pass and a 20-30 mile ride on a load of hay.

The birth of Catherine is probably the biggest mystery of the Sargent family. As events will show, Catherine was the child most favored by John Sargent. In later years, Martha Sargent would not even admit she had a sister named Catherine; while the Crane family considered Catherine to be fathered by John but not borne by Adelaide (Titus, 1977a).

Beside the possibilities that (1) Catherine was indeed Adelaide's child; and (2) Catherine was an illegitimate child born to either John or Adelaide, a third option appears very possible. One or both of the Sargents might have been guardians for Catherine. Kongslie (1891) described an encounter by Sargent with a temporary guardian of a small girl in New Haven, Connecticut. Supposedly, the girl was from Maine and was heir to a large sum of money and John was claiming guardianship for her but was refused by the unnamed temporary guardian. This incident shows that Sargent was capable of assuming guardianship, which could be a source of income.

Also, there was a strange business transaction involving the establishment of a land trust for Catherine by John, 4 miles south of St. Anthony, Idaho. John paid $75 for 5 acres, acting as a trustee for Catherine in 1895. Later John sold the land to his wife for $500. The land was eventually lost for failure to pay taxes (Fremont Co., 1895; 1895a; 1921). The guardian theory is further supported by the later marriage of Sargent's only son, Charles, to Catherine, his "sister" (Washington Co., 1932). Therefore, despite the birth certificate and baptismal record of Catherine, there is some question as to who the natural parents were.

There is no detailed account of the Sargent family's return to Marymere or their life on the ranch during the next 1-1/2 years. However, Sargent does say in his affidavit filed with his homestead application that they returned in the Spring 1893 and spent the Winter 1893-94 on the ranch (J. Sargent, 1904; U.S. Dept. of Interior, 1905). On May 15, 1894, the Sargent's fifth child, Adelaide, was born at Marymere (J. Sargent, 1906a). This was corroborated by information on a baptismal certificate (Church of the Ascension, 1897) and the U.S. 1900 Census of Machias, Maine.

In November 1894, Sargent took his wife and their five children to spend the winter in Wilford, Idaho (Fremont Co., 1895a), and delayed their return in the Spring 1895 "because of Bannock Indian troubles" (J. Sargent, 1904; Browning, 1895-96). The following account in the New York Times showed the involvement of the Sargent ranch (N.Y Times, 1895):

"Regarding the Mary Mere ranch, to which troops have been sent to give protection against the indians, according to a dispatch from Market Lake, Idaho, Mr. Pease said 'the Mary Mere ranch is situated in a wild and mountainous region, fifty miles south of the troops that are present stationed in Yellowstone Park and is many miles from any other inhabitation.

If the indians are nearing the ranch, and it is threatened, it would prove conclusively that they are rapidly moving northward, as fifty miles represents a great distance in that wild and almost impassable region.'"

The family remained at Marymere through 1895 and all of 1896.

On March 26, 1897, a tragic event changed the lives of the Sargent family. On that day, a group of Jackson Hole residents removed a very ill Mrs. Sargent from the Marymere Ranch and transported her by toboggan to the D. C. Nowlin ranch some 50 miles south on what is now the National Elk Refuge. Apparently, they reached the Nowlin ranch on the evening of March 29. The purpose of the trip was to obtain medical aid for Mrs. Sargent. Mrs. Sargent's condition worsened despite all nursing efforts. She died on April 11, 1897, and was buried the next day on the Nowlin ranch (J. Sargent, 1899a).

This event suddenly became a very emotional issue among the local residents. Those feelings were picked up by the newspapers in many sensational and contradictory accounts of the death. The extent of these conflicting accounts is best illustrated in the excerpts from two newspaper stories and from a deposition made by Sargent. On April 3, 1897, The News-Register of Evanston, Wyoming, stated:

"until some four weeks ago a couple of messengers arrived in the settlements requesting some one to go at once to Sargent's, as Mrs. Sargent was dangerously ill and reporting that Sargent was neglecting to care for her and preventing even the children from waiting upon their mother. This strange report, coupled with indignation that such a state of affairs could exist, impelled Mr. and Mrs. D. C. Nowlin to leave the settlements for the Sargent ranch and the succeeding day Mrs. Samuel E. Osborne followed, both ladies being accompanied by six strong snowshoers and toboggans, supplies etc. Upon arrival at the Sargent place they were confronted with the puritan visage of Sargent and ordered off the premises, with all the lordly eloquence of a diseased mind.

But these parties, after having made such a harrowing trip against the wintry elements, had no idea of returning without at least knowing the truth of the messenger's report and upon this determination proceeded against Sargent's protest to investigate. A harrowing and sorrowful sight met their gaze. Lying upon a couch, was a woman, wasted and worn by disease and suffering. Inquiry developed the fact that during her long illness no hand of pity, no heart of love, had been held out to her by the brute who, fifteen years before, had sworn to love, honor and protect her. Lying there alone, neglected and dying, was the mother of his children, while Sargent, steeped in the fumes of opium and morphine, calmly awaited the moment of her death.

Kind and willing hands gave needy assistance and the weak and shrunken form was warmed back to life and today bids fair to survive the months of neglect, and the damnable abuse heaped upon her and her children by the husband and father."

Some years later a different version was printed in the Kemmerer Camera (1913):

"The story of the accident which occurred in 1897 as it has been given to us, is that during the fall the team had been hitched up preparatory to go into town. The two children had been put in the wagon, when the horses started up. Mrs. Sargent ran forward and caught the horses by the bits, and Mr. Sargent coming from the other side grabbed the lines and slapped them over the horses causing them to plunge forward, knocking her down and breaking a leg.

Instead of getting medical aid, Sargent took her into the house and kept her there giving what attention he could, but not believing the leg was broken. During the winter a soldier visited the ranch and reported the condition of Mrs. Sargent to the people in the valley, and they went to that distant ranch home, and brought her out on a toboggan, and sending for a physician and nurse.

About the only evidence which could be secured against Sargent was that of the nurse who stated her belief that death had been caused by neglect and lack of medical attention."

Both of these versions differ markedly from Sargent's chronology of events as outlined in his application for release from jail (J. Sargent, 1899a):

"about February 1, 1897, his wife Adelaide Sargent was taken ill at his said home; that about March 1, 1897, your petitioner dispatched messengers to Jackson Hole, 50 miles distant to summon a nurse for his said wife, one Mrs. Osborne by name; that said nurse arrived at the home of the petitioner on the 7th day of March, 1897, and took exclusive charge of said Mrs. Sargent to care for her and if possible to nurse her back to health; that Mrs. Sargent at this time had been about seven months pregnant; that the condition of Mrs. Sargent did not improve and on the 26th day of March, 1897, over the protest of this petitioner Mrs. Sargent was by certain people of Jackson Hole removed to the residence of one D. C. Nowlin, about 50 miles distant, professedly as it was said for the purpose of procuring medical aid; that said Mrs. Sargent was transported to said Nowlin's in a toboggan over the snow when the weather was severe and blistering and arrived there on the evening of March 29, 1897, very much exhausted; that a few hours thereafter on the same evening said Mrs. Sargent was delivered of a still-born child; that Dr. Woodburn of Rexburg, Idaho and the said nurse Mrs. Osborne were then and there present; that said Dr. Woodburn testified at the preliminary hearing of this petitioner hereinafter referred that said still-born child had, in his opinion, been dead in the womb about two weeks and said Mrs. Osborne testified that in her opinion it had been dead in the womb from 6 to 10 days; that said Dr. Woodburn immediately pronounced Mrs. Sargent beyond hope, that medical science could not save her and about April 1, 1897, left for his home at Rexburg, Idaho, about 90 miles distant; that on the 11th day of April, 1897, Mrs. Sargent died at said Nowlin's and on the following day was buried there."

Following Adelaide's death, John remained at Marymere with one of his daughters until at least May 18 (WY Press, 1897). He then left the ranch and traveled to New York City, where lacking money, he went to work for Swift and Company for 2 years (J. Sargent, 1906a). In the meantime, nurse Hattie Osborne was granted a court judgement against John Sargent for serices rendered to his wife. Since John had left the country, the court authorized seizure of some of his property in the amount necessary to satisfy the judgement (Uinta Co., 1897). Not informed of this transaction or not willing to admit that justice was served, Sargent later claimed his possessions were stolen from him in his deposition for his homestead claim (J. Sargent, 1906a).

In October 1899, John returned to Marymere. He then appeared before the Justice of the Peace Court at Elk presided over by J.P. Cunningham (Fig. 18). The occasion of the appearance was for a preliminary hearing on the charge of second degree murder in the death of his wife, Adelaide (J. Sargent, 1899a). As a result of the preliminary hearing, Sargent was bound over to the Uinta County Jail and District Court in Evanston for trial on the second degree murder charge (WY Press, 1899). On December 8, 1899, Sargent petitioned for release from jail on his own recognizance since he was without funds for bail, he was needed to support two of his children and his health was in jeopardy (J. Sargent, 1899a; WY Tribune, 1900). The court approved this request on December 11 (Uinta Co., 1899).

|

| Fig. 18. Preliminary hearing for John Sargent, murder in the second degree, Justice of Peace Court, Elk Precinct, Oct. 1899. Left to right: Catherine, John and Mary Sargent, Lawyer Ryckman, Justice Cunningham, Sheriff Ward and County Attorney Sammon. (Milward L. Simpson Coll., Acc. No. 26, Neg. No. 17438, Photo B-Sa 732-jd. Archives Div., Amer. Heritage Center, Univ. of WY, Laramie.) |

The murder trial was scheduled for April 9, 1900, in the District Court in Evanston. Witness subpoenas were issued on March 17, 1900. On April 3, 1900, Uinta County Attorney John W. Sammon moved and the court agreed to dismiss the case (Uinta Co., 1900). Reasons for the dismissal stemmed from conflicting testimony among the witnesses and inability to obtain substantial evidence (Kemmerer Camera, 1913).

Ironically, there is still an absence of facts that can be substantiated to describe what really happened to Mrs. Sargent. Two statements may best sum up the situation:

"While the story thruout seems like a tale of the blackest villiany with Sargent as the chief actor, there appears an underlying current of injustice done an innocent man. Sargent is either a villian of the deepest dye or else the worst persecuted man in the United States" (WY Tribune, 1900).

"My own opinion is that she probably became sick of starvation, may have had an accident, which resulted in physical injury, which he had not the skill to treat, and that his fault consisted in being too proud to let his condition be known to those he disliked, and who disliked and distrusted him, but who would nevertheless have not permitted him and his to so suffer. He spoke to me of the occurrence as a proud man would, whose private needs and secret distress had been officiously pried into by foes and strangers who took advantage of his needs to make public his distress, and, under pretense of charity, to degrade him and try to alienate his children. The truth, I think, is that neither side understood the other" (Leek, 1923).

Adelaide's death brought about drastic changes in the Sargent family. Following their mother's death, the children were placed in temporary custody of several Jackson Hole families (Leek, 1923; News-Register, 1897). Such an arrangement did not involve all of the children since on May 18, 1897, Sargent stated that one of his daughters was still living with him at Marymere, presumably Catherine (WY Press, 1897).

Henry C. Sargent, John's father of record, sent one of his brothers to Wyoming immediately after Adelaide's death to return his grandchildren to Machias. Mary, Martha, Adelaide and Charles returned with John's uncle. In Machais, Martha and Adelaide lived with Henry, while Mary and Charles stayed with Adelaide's parents, the Leander Crane family (Titus, 1982; U.S. Census, 1900). For some reason, Catherine was not returned to Machias with the other four children. She continued to have a mysterious life.

While living with their grandfather, Martha and Adelaide were able to take advantage of schooling opportunities that had been unavailable in Wyoming. Martha was married to George Eaton in December 1913 in Machias. Shortly thereafter, she and her husband moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts. After the birth of a daughter, Barbara, she divorced Eaton but remained in Lawrence. She ultimately was employed in a woman's specialty shop in Boston (Fig. 23). She retired from that firm in 1961. Martha died in DeLand, Florida, on May 29, 1979, and was buried in the Sargent family plot in the Court Street Cemetery of Machias (Titus, 1982).

Adelaide attended Machias Normal School where she received her credentials to teach at the primary school level (Fig. 19). She taught first grade in Augusta and then in Houlton, Maine, where she met her husband-to-be (Barton, 1982). On August 2, 1921, she married James Oland Barton in Machias (R. Wright, No date). She died on March 12, 1923, when giving birth to their only child, a son, Robert Barton. Adelaide is buried in the Lincoln, Maine, Cemetery (State of ME, 1923).

|

| Fig. 19. Adelaide Sargent. (Robert Barton Coll., Enfield, ME.) |

Like Martha and Adelaide, Charles' teenage life with the Leander Crane family appears to have been relatively uneventful. The seafaring atmosphere of Machias rubbed off on Charles; and after a relatively brief stay with the Cranes, he enlisted and served in the U.S. Navy from May 10, 1901, to December 24, 1906. He then joined the Merchant Marine and ultimately attended school for ships officers (Military Personnel Records, 1986; R. Wright, No date). Some time around 1913, Charles married Catherine (Washington Co., 1932), his "sister" of record.

With the outbreak of World War I, Charles transferred back to the U.S. Navy as a commissioned officer. After World War I, he elected to remain in the U.S. Navy. Barbara Titus, Martha Sargent's daughter, related how all of the Sargent children, except Catherine, came for a reunion with Charles in Boston in November 1919. Charles took all of them out to dinner at the Copley Plaza. At that time, he was an officer on a ship in the port of Fall River, Massachusetts. This was the last time all of these Sargent children would see each other (Titus, 1985).

On March 18, 1920, Charles was a Lieutenant Commander serving as Captain of the Transport U.S.S. Yale (Fig. 20). He was waiting for his replacement so that he could be reassigned as Captain of another Navy ship (R. Crane, 1920). Sometime during late 1920 or early 1921, Charles was diagnosed as having tuberculosis and was to be transferred to Arizona for treatment. Unfortunately, before his replacement arrived, Charles died aboard his ship in the port of Fall River, Massachusetts, in December 1921. The cause of his death was a lung hemorrhage. He was buried in a cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island (Titus, 1985a).

|

| Fig. 20. Charles Sargent. (Barbara Titus Coll., DeLand, FL.) |

As mentioned previously, John left Marymere after his wife's death and may have taken Catherine with him. The other children were already in Machias. The reasons for his departure, according to Sargent's deposition to the U.S. General Land Office in Evanston, Wyoming (J. Sargent, 1906a), were: "That he was forced by deception and fraud and the kidnapping of his four year old daughter in May 1897, to go East." What he meant by "fraud" and "kidnapping" is unknown but Catherine was 4 years old at that time and probably was the daughter he was referring to.

Along with her sister Adelaide and her father, Catherine was baptised in New York City on August 1, 1897 (Church of the Ascension, 1897). After that ceremony until 1899 in Jackson Hole, there is no information on Catherine's whereabouts except that her father was working in New York City to support her (J. Sargent, 1906a). On October 28, 1899, she appeared with Mary in a photo taken at John's preliminary murder hearing at Elk, Wyoming (Fig. 18). Barbara Titus, daughter of Martha Sargent, reports that she was told by relatives that John took Mary and Catherine back to the West with him when he returned in 1899. Both girls disliked the East (Titus, 1978a).

After returning to Jackson Hole, Catherine and Mary were then taken to the Sister's school in Ogden, Utah, according to Sargent's application for his release from jail (J. Sargent, 1899a). The Sacred Heart Academy, operated by the Sisters of the Holy Cross from 1878-1956, was a boarding school in Ogden (Louise, 1985). This was probably the school John mentioned. After his release, the Wyoming Tribune (1900) reported that the two girls were attending school in Salt Lake City and living with their father who was working for the Oregon Short Line Railroad.

From Salt Lake City, Catherine apparently accompanied her father to Marymere in July 1900 (V. Lawrence, No date). In the Fall 1902, Catherine went away to school for 5 years in Racine, Wisconsin, living with a family named Lynn (Fig. 21) (J. Sargent, 1906b; C. Sargent, 1905). During this time, there is further documentation that Catherine was a favorite child of John's. On April 17, 1907, John D. Sargent made out a deed of trust making Catherine a gift of his estate with Herbert H. Drake as trustee for Catherine (Uinta Co., 1907). Catherine's last documented stay at Marymere is the photograph taken in 1908 (Fig. 22).

|

| Fig. 21. Catherine Sargent, Nov. 14, 1902. (Nat'l Archives & Record Serv. Evanston, WY, Homestead Final Certificate 1024 and Misc. Letter 353992. Gen. Br., Civil Archives Div., Wash., D.C.) |

|

| Fig. 22. John, daughter Catherine and Sargent's black filly in front of the Sargent cabin, 1908. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

From 1908 on, Catherine's activities were very vague. There were many rumors which cannot be substantiated. The first hint of her marriage to Charles was in 1913 when Henry C. Sargent, John's father, wrote to the District Court, Kemmerer, Wyoming, after receiving notification of John's death. He mentioned that Charles and Catherine were living in New York City, address unknown (H. Sargent, 1913). In 1920, Ruth Crane who was brought up with Charles in the Leander Crane family, reported she met Charles in Philadelphia and at that time Charles was married and had four children. She said Catherine was living with them but she didn't mention that Catherine was his wife. Ruth stated that Charles' oldest child was 6 years old; therefore, the marriage could have taken place in 1913 (R. Crane, 1920). When Charles died in 1921, Catherine was at the funeral. She then disappeared until 1932.

On May 3, 1932, Catherine applied to the Washington County Probate Court for her children's share of their great grandfather's (Henry C. Sargent) estate (Washington Co., 1932). From this deposition, only two daughters and one son were alive on that date. This deposition proves that Catherine married her brother of record, Charles, when she certified that Alice, Charles, and Dorothy were the only surviving children "of my late husband, Charles Hemenway Sargent, deceased." The last information about Catherine was her application on October 22, 1940, for her share of Henry C. Sargent's estate, claiming she was his granddaughter. Unfortunately, the Washington County Probate Records lacked any current address for Catherine at that time (Washington Co., 1940).

Mary Sargent's (John's oldest daughter) early life closely parallels Catherine's early childhood. After her mother's death, she stayed with the Leander Crane family along with Charles, her brother. Unhappy in Machias, Mary returned with Catherine and her father to Marymere in 1899 (Fig. 18) (Titus, 1978a). Again with Catherine, Mary attended school in Ogden and Salt Lake City when their father was in jail and when he worked for the railroad (J. Sargent, 1899a; WY Tribune, 1900).

On November 3, 1902, at the age of 15, Mary Sargent married Fred Cunningham, brother and partner of James Pierce Cunningham, in St. Anthony, Idaho (Fremont Co., 1902). Mary may have been living with the J. Pierce family as early as 1900, for Pierce and Margaret Cunningham had no children and it was reported that they reared some of the Sargent children (Apple, 1960; Leek, 1923). The Fred Cunningham ranch was located southeast of the now preserved Pierce Cunningham Cabin, a historical feature in Grand Teton National Park (Allen, 1981).

Mary had been mistreated by Fred and had lived an unpleasant life with him (W. Lawrence, 1978). Sometime in 1912, she left Fred without his knowledge and went to Ashton, Idaho (Allen, 1981). She and her son accomplished this by walking several miles in the rain to the Fred Feuz ranch. Their forlorn appearance made a lasting impression on Caroline Feuz Oliver as a young child. Sympathetic to their plight, Caroline's father took them to Moran where they caught a freight wagon to Ashton (Oliver, 1986).

Shortly after, Fred Cunningham also left Jackson Hole. The exact date was not established. The Wyoming Stock Growers Association (1912) did not record Fred's cattle assessments after 1911. The Jackson's Hole Courier (1915) reported he was hauling hay in January 1915. As a young boy and neighbor, Marion Allen (1986) remembered Fred returning to Jackson Hole to help his brother, Pierce, for a year during World War I. Other neighbors, who are still living in Jackson Hole, did not know what happened to Fred. Steven Leek (1923) reported he committed suicide. Marion Allen (1986) recalled his father, J. V. Allen, met Fred in Idaho around 1918. Fred was very ill at that time and died soon afterwards.

Mary's and Fred's only child, Roy, was born in 1905 (U.S. Census, 1910). When Mary returned to Jackson Hole, Roy stayed with the J. Pierce Cunninghams periodically (Taylor, 1985). Like his mother, he had trouble holding a permanent job and he did not enjoy a good reputation with residents (W. Lawrence, 1978; Briggs, 1985). Roy married and left Jackson Hole in the early 1930s.

After leaving her husband, Mary led an unsettled life. In 1913, just before his death, John reported she was in a theatre company in the vicinity of Seattle, Washington (J. Sargent, 1913a). As mentioned previously, Mary came from the West Coast to participate in the 1919 reunion with Charles Sargent in Boston (Titus, 1985a).

Mary Sargent was in and out of Jackson Hole many times during the period between the 1920s and 1940s. W. Lawrence knew Mary when she was living with Herb Whiteman and working for Ben Sheffield in Moran, Wyoming, in the early 1920s. W. Lawrence (1978) said, "It was hard for her to concentrate on a job or keep a job. She would hang around Moran and talk to the workers." Ben Sheffield Jr. recalled that Mary worked for his father several times at Moran (Sheffield, 1985). In 1927, she was married to a man named Curtis (Washington Co., 1927). This marriage only lasted a couple of years, for in 1932, she was married to a Mr. Beal (Washington Co., 1932a). Sometime during or between these marriages, Mary worked for J. Pierce Cunningham when he was managing a hotel in Victor, Idaho (Taylor, 1985).

In the late 1930s, Mary lived in California, returning to Jackson Hole for a month in summer for about 3 years. Each time, she camped on the site of the Sargent homestead. W. Lawrence would provide her with a tent. Her purpose was to look for family valuables which she claimed were buried near the homestead (W. Lawrence, 1978; 1981). Marion Allen (1985) also remembered seeing Mary at the Ward Dance Hall in Jackson, Wyoming, in the late 1930s. During the 1932 visit, Mary had her mother's body moved from the Nowlin ranch site to the Jackson City Cemetery.

On September 19, 1947, she married her fourth husband, George C. Sears, in San Rafael, California (State of CA, 1947). In the 1950s and 1960s, she continued to visit Jackson Hole. Mary's 1950 trip was highlighted by a reunion visit to Marymere with her sister, Martha Sargent Eaton (Fig. 23) (Jackson's Hole Courier, 1950). Mary out-lived her husband but remained in San Francisco where she died on September 4, 1984 (State of CA, 1984), at the age of 97.

|

| Fig. 23. Reunion of Mary Sargent Sears (l) and Martha Sargent Eaton (r), Jackson Lake, 1950. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

The general appearance of John D. Sargent is best captured in Fig. 24. He was around 6 feet tall, slim in build with fine features, straight black hair and black mustache. His dress was a mixture of Western and Eastern clothing (Burt, 1924). Hilda Stadler, who knew Sargent in his later years and lived in his cabin in 1899, wrote, "I remember him well, he had a hunted look—like he was afraid the devil would get him" (Stadler, 1956).

|

| Fig. 24. John Sargent, Dec. 1912. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Sargent was a Doctor Jekyll and a Mr. Hyde. He possessed a violent, even maniacal temper (Burt, 1924; Titus, 1978); yet as Burt went on to say, "in all my life I have never seen anyone kinder to a nervous, untrained animal than this man, twice accused of murder, was to his black filly." Accounts written in Sargent's journal present vivid testimony that he was a sensitive, literate person (J. Sargent, 1892; 1904a). His library collection and phonograph demonstrated an interest in and appreciation for the fine arts and humanities (Lincoln Co., 1914). At the same time, John seemed to be a religious man. He was baptized with two of his daughters in 1897; and in 1905, he transferred by warranty deed 1 acre of his homestead to the Episcopal Church, through the Rt. Reverend James B. Funsten, Bishop of Boise, for the purpose of constructing an Episcopal chapel, a rectory and a burial ground (Church of the Ascension, 1897; Uinta Co., 1905a).

From the very beginning of his stay in Jackson Hole, Sargent displayed a life-style and a fierce independence characteristic of his New England background but foreign to the early homesteaders in the valley. Such things as his piano, phonograph, library and pool table were amenities which would serve to soften the impact of the family's isolation (Fig. 12). Nevertheless, John's behavior and his belongings were undoubtedly the very non-western facets that triggered comments about his eccentricity and were a source for envy and antagonism, particularly after his wife's death (Allen, 1985).

Furthermore, John was disowned and severed from his last family ties by Henry C. Sargent, his father of record, following Adelaide's death (Titus, 1978; 1978a). Except for Mary and Catherine, he was cut off from his other children by distance and his lack of money after returning to the West in 1899. As stated before, Sargent lost some of his belongings, furnishings and livestock when he was forced to leave Jackson Hole after his wife's death (Uinta Co., 1897). These had to be replaced.

The location of Marymere added to Sargent's stress. While some new neighbors were established after 1897, the isolation remained as a potential stress factor where John was the only adult of the family for a year and alone for most of the 4 years prior to his second marriage in 1906.

In the midst of all of his personal problems, Sargent went on a crusade against the illegal killing of elk and trespassing on the Forest Reserve in Jackson Hole. His letters of complaint to the Commissioner of the General Land Office not only stated the problem but included the names of his neighbors and other residents of Jackson Hole as violators (J. Sargent, 1901). While these letters identify several real problems, the following excerpt also indicated Sargent's growing paranoia about the residents of Jackson Hole:

"A citizen of Wyoming who lives in this reserve and strictly obeys all laws, and tells the truth about those who do not, can not make a living here because of slander, and conspiracy, and blackmail, he must suffer from those who are lawless characters of this reserve" (J. Sargent, 1901a).

The previous letters triggered an investigation by the Army Unit from Yellowstone National Park and a Forest Inspector. The following excerpts from Forest Inspector Macrum's report detailed the general game law violation problem in Jackson Hole as he and the Army investigators found it in 1901:

"Constant inquiry was made along the way regarding violation of the game laws, and while little testimony could be obtained that would convict in a court of justice, yet enough was found to convince us that a number of persons are living on the reserves who make a living therefrom, largely from game.

Difficulty in securing testimony for conviction of violators of the game laws arises from the following causes: First, nearly all persons living in the Jackson Hole country, in one way or other, are trespassers, and consequently afraid to testify lest they in turn be caught; second, they are afraid that personal danger would follow giving information; third, the justice court being elective, great leniency is shown to offenders when brought before it, hence no adequate penalties are inflicted; fourth, the State game warden, a taxidermist, and his deputy, live among those who violate the laws and are lax about making arrests. About the only informations made are those growing out of spite....

From what I saw and heard while there I think this is the most lawless place I have seen."

With respect to trespassers on the Forest Reserve, the foregoing investigators cited 14 violators, recommending removal of all individuals having no legal right of residence (Macrum, 1901).

While Sargent and the investigators were probably correct, survival in Jackson Hole was very difficult and the means for that survival were very limited. Consequently, those early residents utilized every option in that struggle, illegal or not. Sargent's letters only added more fuel to the fires of animosity already in existence.

With the departure of Catherine to Wisconsin in October 1902 for 5 years and Mary's marriage to Fred Cunningham in the same fall, Sargent was left alone at Marymere to dwell on his personal problems. At this time, Sargent concentrated on the acquisition of title to his homestead land. Prior to this time, John had exercised a squatter's claim to the homestead; however, no filing could be accomplished on the unsurveyed lands. With the establishment of the Teton-Yellowstone Forest Reserve, all of these squatter claims were evaluated by Reserve personnel as to their legitimacy as an agricultural settlement within the Reserve. Such an evaluation was made on December 20, 1902, with the recommendation to permit Sargent to file on the land (Wolff, 1902). The formal transmittal of this report by the Forest Supervisor was not approved until December 14, 1903. That report was not stamped with a date of receipt by the General Land Office in Washington, D.C. until July 9, 1906 (Miller, 1903). This example of communication and transmittal delays and other similar problems were to continuously plague Sargent's efforts to obtain title to his homestead. Completion of his homestead filing was delayed further by: (l) slow exchanges of mail correspondence; (2) delayed land surveys; (3) Jackson Lake irrigation land withdrawals for the Minidoka Project by the Reclamation Service; (4) contradictory decisions within the General Land Office concerning appropriate homestead application processing procedures; and (5) Sargent's own failure to comply with homestead regulations (National Archives, 1902-08).

In his efforts to obtain timely and favorable consideration for his homestead application from the General Land Office, Sargent called upon an array of persons for assistance. The most helpful of these individuals were the following: U.S. Representative from Colorado, Franklin E. Brooks, House Committee of Agriculture; U.S. Representative from Wyoming, Frank W. Mondell, Chairman, House Committee Irrigation of Arid Lands; and Robert S. Spence, Attorney, Evanston, Wyoming (National Archives, 1902-08). Finally, on March 23, 1908, John D. Sargent's homestead application was approved (U.S. General Land Office, 1908) under Final Certificate No. 1024 for 160.61 acres.

Sometime in the 1900s, Sargent operated a store in a small log cabin next to the Military Highway and Freight Road on the north shore of Sargent's Bay near his homestead (V. Lawrence, No date). Ben Sheffield Jr. (1985) remembered buying candy there and Struthers Burt (1924) saw signs "announcing that lemonade and candy and tobacco could be bought." Two other signs on the store characterize its reputation with travelers. On the door was a sign "M & M" for Marymere; but local people facetiously said it stood for "Milk and Music," which were the main items for sale. Milk came from John's cows and the music related to cylinder phonograph records. The other sign read, "All under a dollar leave it—Over a dollar charge it" (Allan, 1976). From the latter sign, one might deduce that it was a self-serve establishment with a limited inventory.

In addition to the store, Sargent became an agent for the Victor Talking Machine Company sometime around 1910. He was advertising his dealership via the mails with the following handwritten postcard message (V. Lawrence, No date):

"Victor talking machines

Records and needles

at Montgomery Ward Co.

Chicago prices

at Sargent's on the Lake.

New stock in Aug 5, 1910

Machines $17.50 up

Records 35c to $6.00 each

No dealer in the U.S. can

undersell me in Victors

and records.

Sargent-Victor Dealer"

When John came to Moran for his mail, he frequently brought his Victor phonograph for neighbors to hear (Sheffield, 1985).

Another way Sargent tried to earn money from travelers was by renting his boat. F. T. Thwaites (1903) on a trip to Yellowstone Park in 1903 recalled,

"We camped on a small bay not far from Sargeant's Ranch and soon were visited by John Dudley Sargeant, the Hermit of Jackson Lake. He was a great talker, very nervous, and obviously an Easterner. He stayed for supper, and offered to rent us his boat for less than the 'quarter of a dollar for a quarter of an hour' which he advertised on signs."

Throughout Sargent's communication with the General Land Office, he repeatedly referred to the problems of winter travel and mail service in Jackson Hole (National Archives, 1902-08). Allen (1981) vividly described the hazards of that winter travel in relation to the 1908 death of a Mr. Snow who was wintering at the Marymere with his wife and Sargent. Mr. Snow supposedly got "cabin fever." He attempted to walk on the ice of Jackson Lake to Moran and became lost and froze to death. While there is no absolute verification, Sargent had an aunt whose married name was Snow and the family could have been the one mentioned (Washington Co., 1888). Tragedy seemed to be a constant companion for John Sargent.

A more personal account of those oversnow travel conditions is provided by Sargent describing one of his spring trips when he was returning to Marymere from a winter outside Jackson Hole (J. Sargent, 1904a):*

"Saturday the 9th, after having missed the tri-weekly stage of Wednesday, I got off on the stage for Squirrel P. O. Idaho, 24 miles East of St. Anthony. The ride half way was all right but the last half was pretty bumpy because of snow and ice in the road necesitating our changing to a horse sled 7 miles before reaching Squirrel P. O. when we arrived at 3 P.M. I found about 2 ft. of snow on level at Squirrel and it looked good to me for it was the first of that sort I'd seen since I left home in December. After looking over the Highland Ranch that afternoon with me friend the manager Mr. C. and admiring his well-wintered Herfords I got out my old ski; waxed them up for business and the next morning Sunday the 10th, I began my ski trip with L. my sole companion on the fifty mile trip from there home.

When we started out from the Highland Ranch it was quite cold and the snow crusted hard but by the time we reached the last ranch we'd pass on our trip, 7 miles East of the Highland Ranch, the day became hot and the glare of the sun shining from a flawless azure sky almost unbearable to our eyes so we retraced our trail a mile and spend the Sunday at Judge Kelly's Ranch and enjoyed hearing our last music (there was a Chickering piano on this far away ranch) through the kindness of the Judge's daughter, before skiing out into the wilderness.

Rather late the next morning we again got off on our journey, the ski running well till noon when it was so hot and the sun so hard on our eyes we decided to camp on some rocky cliffs over the valley of Squirrel Creek till evening.

The rocks sloped at the south and were bare of snow so we were very comfortable in the warm sunshine. Thirty miles east of us was the entire west face of the Teton range with the Grand Teton and Mt. Moran ashy gray against the vivid blue of the sky beyond and the main range snowwhite, with black masses here and there where the timber grew.

Far to the west we could see the ragged Saw Tooth range and due South of us the half circular range that bridges the Teton Basin, now thickly settled. Over all was a flood of bright sunshine and we were really warm under its glare although there was nearly 2 ft. of old settled snow on a level all about us but where we had perched ourselves on the rocks.

Mounting our ski just before Sundown we struck into the timbered parks that extend up to the base of the Teton Range, and steering our course straight East by Northeast we kept at it all night till we arrived at the Forest Ranger Cabin on Squirrel Creek Meadows at sunrise the next morning. The old snow was on a level with the roof of the cabin and would average 6 ft. on a level all over that region.