|

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 5:

Prospectors and Miners

.... "Uncle Jack" Davis, a colorful character, devoted himself to prospecting in the Snake River Canyon, where he had a crude cabin near Bailey Creek. When he died in 1911, his valuables consisted of $12 in cash and about the same amount in gold amalgam. Not much return for at least 20 years worth of prospecting. . . .

|

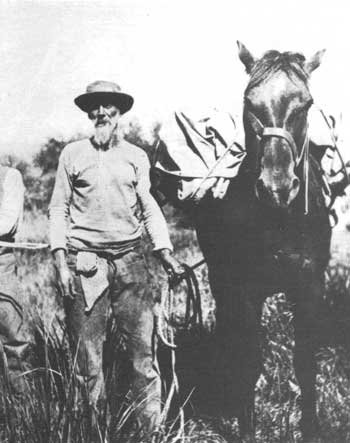

| "Uncle Jack" Davis listed his occupation as "gold miner" in the 1900 census. Davis prospected in the Snake River Canyon, where he had a crude cabin near Bailey Creek. National Park Service |

The California gold rush occurred in 1849, triggered by the discovery at Sutter's Mill. By the end of the year, California's population had expanded to 100,000 people, most of them Anglo-Americans bitten by the gold bug. At first, pickings were easy. Individuals or small groups engaged in placer mining, a relatively simple process that required only a shovel, pan, and strong back. As the rivers and streams played out, companies displaced individualistic prospectors; large amounts of capital were required to excavate mines and construct mills to extract gold from tough quartz. [1] Prospecting became a way of life to these displaced frontiersmen. Perennial optimists, they dispersed throughout the Rocky Mountain West and discovered gold in Colorado, Nevada, and British Columbia in 1858. In 1862, prospectors located gold in Montana, precipitating the rush to Bannock City and Virginia City in 1863. From southwest Montana, ever-hopeful prospectors made their way into Jackson Hole.

In 1863, Walter W. DeLacy joined a party of prospectors intent on seeking gold "on the south branch of Snake River to its head." DeLacy produced a map in 1865, and published an account of the trip in 1876. Hence, the expedition is remembered for its accomplishments in exploration rather than striking it rich. They failed to find the mother load of gold. [2] DeLacy considered himself "pretty well fixed for such a trip," having "two good horses," provisions for about 40 days, weapons, and $10 in gold dust. He did not mention them, but he also must have brought the miner's traditional tools, a pick, shovel, and washing pan. He joined the band on the Beaverhead River in Montana and was elected captain of the expedition, even though few of the miners knew him. He attributed his election to the fact that "it is frequently a great point in your favor that no one knows anything about you." [3]

DeLacy set out on August 7, 1863, leading 26 prospectors. Since most of them had arrived only recently from the gold fields of Colorado and Montana, none had first-hand knowledge of the Jackson Hole country. Only one, a prospector named Hillerman, had prospected a portion of the south Snake; hence he served as a guide. Another party joined them, increasing their number to 42. The miners' frontier attracted more than its share of disreputable characters, and this expedition was no exception in DeLacy's judgment. He recalled that vigilantes, presumably in Montana, had banished Hillerman for complicity in a murder. Another prospector, named Gallagher, tried to raise a party to attack and steal horses from a band of Shoshone camped adjacent to one of their bivouacks. Fortunately, "respectable" members of the party dissuaded him. Some time later, vigilantes executed Gallagher.

DeLacy established and supervised a routine. The group marched once per day, camping early so men could prospect until nightfall. Pickets were posted to guard against Indians. On August 19, they came to the confluence of the Salt and Snake Rivers, where smoke from forest fires obscured the surrounding mountains. The next day, DeLacy's band entered the Snake River Canyon, negotiating a trail "about one hundred feet above the river, which was very narrow and difficult, and had apparently been very little used for a number of years." Travel was slow and dangerous; a pack animal and horse tripped and tumbled down the steep slopes. DeLacy's band made about 12 miles and camped in a very poor location. This camp is difficult to locate, as DeLacy's descriptions and mileage estimates are imprecise. They traveled ten miles the next day and camped in a small bottom along the cottonwood-lined river. DeLacy noted that the geographic formations had changed from limestone to sandstone. On August 22, the miners crossed to the left bank of the river (the north or west bank) after traveling three miles. Another five or six miles over comparatively open country brought them to the mouth of the Hoback River, where they set up camp.

For the first time, prospectors dipped their pans in the waters of Jackson Hole, hoping to find pay dirt. DeLacy noted that their guide, Hillerman, had never been this far up the Snake River. (Hillerman and a partner apparently had entered the Snake River Canyon in 1862.) [4] They camped an extra day at Hoback Junction, dispersing to prospect the Snake, Hoback, and nearby tributaries, where every one found plenty of "color," but none in profitable quantities.

On August 24, they moved up the Snake River 11 miles, camping on a stream "coming in from the northeast." Based on mileage traveled and DeLacy's description, this is possibly Spring Creek. Small groups ventured out to prospect and hunt, but no one experienced success. DeLacy observed that "up to this time and for a long time after we saw nothing larger than rabbits." On August 25, they continued north passing between two buttes, obviously traveling up Spring Gulch between East and West Gros Ventre Buttes. DeLacy described the valley as a large and extensive one. "It is one of the most picturesque basins in the mountains. It is covered with fine grass; the soil is deep in many places and it is capable of settlement, and will, in the future, be covered with bands of cattle and sheep." They crossed the Gros Ventre River and stopped to pan for gold. The miners found plenty of "color," but pressed on across flats, "part of which was covered by the largest and thickest sagebrush that I have ever seen." Based on DeLacy's description, they camped on the east bank of the Snake, opposite Cottonwood Creek. The next day, the prospectors followed the Snake River north, skirting around the Snake River Overlook and camping, somewhere west of where the Cunningham Cabin is located today.

On August 27, they crossed the Buffalo Fork. There, they agreed to move on to Pacific Creek, where they would set up a base camp and explore the surrounding country. At Pacific Creek, the band of 42 built a corral, then participated in a meeting. They agreed to break up into four parties; one group would serve as camp guards while the others prospected. To prevent anarchy in case a discovery was made, the assembly agreed that each individual would be considered a discoverer. Every member would be entitled to five claims of 200 feet each. The prospecting parties left on August 28 and returned the 31st. The exact areas explored are unknown. One group traveled about 20 miles up the Buffalo Fork, but like the others, had little success. One party did report a stratum of coal along one of the streams.

|

| Miners Frank Coffin, Don Graham, and Jim Webb gave up this mine on Pilgrim Creek, claiming that "the gold couldn't be retrieved." Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Discouraged, the expedition broke up, one party returning south, DeLacy and 27 others set out on September 2, following the Snake River to Jackson Lake. They traveled north, about 18 miles from Pacific Creek, striking a trail that ran northwest and camped at the inlet of Jackson Lake. With some apprehension, DeLacy recalled that the mountains to the north appeared to be on fire. They also found fresh horse tracks, which they presumed to be Indian signs, but they never saw Indians in Jackson Hole. From here, they moved on to the Yellowstone country.

DeLacy's narrative is significant for the information it provides about Jackson Hole between the end of the fur trade in 1840 and the arrival of settlers in the 1880s. It is the first record of frontiersmen seeking valuable minerals in Jackson Hole. More important, these miners did not hit pay dirt or the mother lode. The landscape of this valley would look much different today had there been a strike. Hundreds of miners would have stampeded into the valley and boomtowns would have sprung up. The adjacent forests would have been denuded to provide lumber for buildings, millraces for placer mining, and timbers for shoring up shafts and tunnels. Given the boom-and-bust character of mining, the mines and towns would have been abandoned, leaving eroded hillsides, small mountains of tailings, and hillsides scarred by hydraulic mining. This pattern occurred in California, Nevada, Colorado, and Montana.

DeLacy's account strongly suggests that Jackson Hole was unoccupied. He found no trapper cabins or isolated homesteads in the valley. Although he was concerned about encountering Indians, DeLacy reported only fresh horse tracks, which he took to be an Indian sign. He reported no camps or, for that matter, signs of Indian villages in the valley. There were distinct Indian and trapper trails in the area. The "little used" trail through the Snake River Canyon reinforces the contention that it was not a major route into Jackson Hole. The trail DeLacy's party struck east of Jackson Lake was a major trail through the valley. Finally, his observations concerning forest fires, the lack of wildlife, and the vegetation are useful in reconstructing the ecology of the region prior to settlement.

Although the DeLacy expedition was unsuccessful, prospectors did not give up on Jackson Hole. In 1864, the George Phelps-John C. Davis party entered Jackson Hole from the Green River valley. The miners crossed Two Ocean Pass and traveled into the Yellowstone country. [5] Between 1864 and 1877, miners conducted more extensive operations. Traveling across the sagebrush flats east of the Snake River in 1878, Orestes St. John found prospect pits and the remains of a ditch north of the Gros Ventre River. St. John was told that prospectors constructed it about 1870 or 1871. [6] The ditch ran from near the Teton Science School to Schwabacher's Landing on the Snake River. Ditch Creek derived its name from this early water diversion, which is still known as Mining Ditch. [7]

|

| Though gold mining in Jackson Hole was never profitable, some miners were successful retrieving other minerals. This man and his dog are working a talc mine on Owl Creek. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Very little information is known to exist concerning these mining ventures. Possibly, prospectors entered Jackson Hole about 1870 from the small mining camps of South Pass City, Atlantic City, and Miners Delight. Misled by exaggerated reports of gold strikes, some 2,000 prospectors had descended on the southern end of the Wind River Range in 1868 and 1869. They were disappointed. Although several profitable holes were found, the yields were never great and by 1870 the "boom" was over. Disappointed stragglers may well have tried their luck in Jackson Hole. [8]

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of the miner's frontier in Jackson Hole is a lurid tale of murder, known as "the Story of Deadman's Bar." The incident occurred in the summer of 1886, just a short two years after the first settlers arrived in Jackson Hole. Four prospectors from Montana—Henry Welter, T H. Tiggerman, August Kellenberger, and John Tonnar—came to the valley to set up placer mines on the Snake River. Lured to Jackson Hole by stories of gold-rich gravels, they located a claim along the Snake River near Snake River Overlook, set up camp, and began work. Later that summer, a boating and fishing party found the bodies of Welter, Tiggerman, and Kellenberger weighted down by rocks at the edge of the river. A sheriff's posse arrested Tonnar in Teton Basin at the ranch of Emile Wolff, who later moved to Jackson Hole. Tonnar was tried for the murder in Evanston, Wyoming. He claimed self-defense and, since there were no eyewitnesses, the jury acquitted him. The site of the murders has since been known as Deadman's Bar. [9]

One mining company attempted to locate gold in Jackson Hole in the 1880s. Harris-Dunn and Company was formed in 1889, after a man known only as Captain Harris visited the valley and located a mine on Whetstone Creek in the present Teton Wilderness. Harris and a man named Dunn formed a joint stock company. The company built cabins, sluices, and a sawmill, and began operating a placer mine. The sluice box consisted of four-inch-thick planks pitted with holes drilled by a two-inch auger. The gold was supposed to settle in the holes, but in practice they filled with gravel. In 1895 or 1896, James M. Conrad constructed a ferry near Oxbow Bend to transport supplies to the mine, then owned by the Whetstone Mining Company. Whether Harris and Dunn sold out or changed the name of their company is unknown. By 1897, the mining operation had shut down. [10]

The presence of "color" in the Snake River drainage continued to entice speculators. Around 1900, 160-acre placer claims were filed up and down the Snake River, from Jackson Lake to Menor's Ferry. But, the prospectors failed to locate the elusive bonanza of gold and the claims lapsed. Shadowy prospectors dug small tunnels in Avalanche and Death Canyons; the foundation of a prospector's cabin still exists in upper Death Canyon. Perhaps they were the work of John Condit and Andrew Davis, who listed their occupations as gold miners in the 1900 census. "Uncle Jack" Davis, a colorful character, devoted himself to prospecting in the Snake River Canyon, where he had a crude cabin near Bailey Creek. When he died in 1911, his valuables consisted of $12 in cash and about the same amount in gold amalgam. Not much return for at least 20 years worth of prospecting. About 1905, E. C. "Doc" Steele and several partners located placer claims on the Snake. They excavated the Steele Ditch from Spread Creek. Settlers used it later to irrigate hay fields. [11]

There was plenty of "color" in the rivers of Jackson Hole, but in concentrations so small that placer mining was not feasible. No one ever found the mother lode—that is, the source of gold. DeLacy tried and failed, and all that followed him tasted failure too. After homesteaders populated the valley, some earned a little extra cash through placer mining. No fortunes were ever made, however, and the mining frontier had little impact on the history of Jackson Hole.

Notes

1. Ray Allen Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 529-530.

2. Walter W. DeLacy, "A Trip up the South Snake River in 1863," Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana, 1 (1876):113-118, transcript in the Grand Teton National Park Library.

4. Ibid. Hillerman informed DeLacy that his partner had shot himself accidentally, then died of the wound.

5. Haines, The Yellowstone Story, 1:68.

6. St. John, "Report of Orestes St. John," Eleventh Annual Report, p. 445.

7. Elizabeth Wied Hayden, From Trapper to Tourist in Jackson Hole, 4th ed., with revisions (Moose, WY: Grand Teton Natural History Association, 1981), pp. 29-30.

8. T. A. Larson, History of Wyoming (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), pp. 112-113.

9. Fritiof Fryxell, "The Story of Deadman's Bar," Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole, pp. 38-42. Fryxell's story of this incident remains the most reliable account, as it was based on an interview with Emile Wolff, who had first hand knowledge of the incident.

10. Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, p. 30; Noley Mumey, The Teton Mountains: Their History and Tradition (Denver: Artcraft Press, 1947), pp. 359-361; and National Archives, Record Group 49, "Records of the Bureau of Land Management," Homestead Certificate 373, Lander, J. Conrad, 1902.

11. Census of the United States, 1900, Wyoming, Uinta County, Enumeration District 65, Jackson Precinct, Elec. Dist. 15, Schedule 1, Population, 9 sheets; and Fritiof Fryxell, "Prospector of Jackson Hole," Campfire Tales, pp. 47-51.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grte/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2004