.gif)

|

My Trips with Harold Ickes: Reminiscences of a Preservation Pioneer |

|

My Trips with Harold Ickes:

Reminiscences of a Preservation Pioneer

by Horace M. Albright

Foreword by Frederick L. Rath, Jr.

|

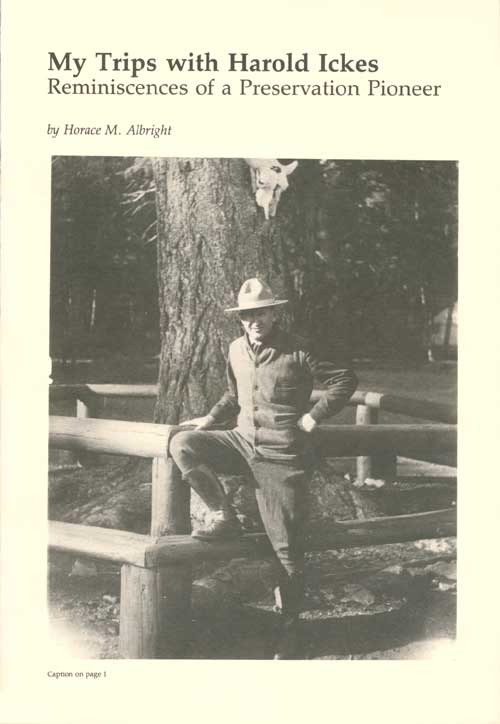

| Horace Albright strikes a pose in Yellowstone National Park in 1922. Albright was superintendent of Yellowstone from 1919 to 1929, while also serving as principal assistant to National Park Service Director Stephen Mather. Courtesy, National Park Service (NPS) History Collection, Harpers Ferry. |

Foreword

My long friendship with Horace Albright, the indomitable second director of the National Park Service, began in the late 1940s when I served as historian for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt National Historic Site at Hyde Park, New York. Albright had been a central figure in the creation of the service, and as long as I knew him, he was always full of stories about its first few decades.

Therefore when I last visited with Albright, aged 97, in a nursing home in California in February 1987, I was not surprised to find him working on a manuscript. Soon I was as fascinated by his remembrance of things past as was Hugh Sidey, who memorialized Albright in the December 23, 1985, issue of Time magazine as a young man "bursting with energy" and "possessed by a vision of how to preserve the nation's grandeur."

Some six weeks after my visit Horace Albright died, but the manuscript he was working on was transcribed and edited by his daughter, Marian Schenck. She felt that in spite of the innumerable words written by and about her father, these reminiscences revealed new information about how a series of Washington-based trips taken by Albright with Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes promoted the cause of historic preservation in the Park Service.* I agreed and now there is this chance to share it.

*Portions of this story have been previously described in The Birth of the National Park Service, The Founding Years, 1913-33 by Horace M. Albright as told to Robert Cahn (Salt Lake City: Howe Brothers, 1985), and in Wilderness Defender: Horace M. Albright and Conservation by Donald C. Swain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970).

Horace Albright came to Washington in 1913 when he was offered a job as confidential secretary in the office of the secretary of the interior for what he called the "magnificent salary of $1,200 a year and an opportunity to complete law school in Washington by going to Georgetown University at night." Somewhat to his surprise—but to his delight—he soon found himself immersed in a study of national parks and monuments and the need for a new bureau to administer them. By January 1915 he was principal assistant to a wealthy businessman and early conservationist from Chicago, Stephen Mather. Together they were charged with framing the legislation that would bring the National Park Service into being on August 26, 1916. On that night Albright's personal zeal convinced President Wilson to sign the bill earlier than expected. Albright triumphantly sent a night letter to Mather, who was in California: "Park Service bill signed... Have pen used by President in signing for you."

Thereafter Mather, the first director, and Albright, his assistant director, worked to establish a service that became a model for the rest of the world. Mather was frequently ill in the years ahead, and Albright often filled in as his principal deputy. On January 12, 1929, in the wake of Mather's paralytic stroke and subsequent resignation, Albright became the director of the service. During the difficult years of world-wide depression that followed, his priorities were to improve the parks and to encourage the American people to appreciate and conserve their heritage.

He also moved more forthrightly into the field of historic preservation. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, and appointed Harold Ickes his secretary of interior, Albright not only had new bosses, but a possible chance to influence them so that he could realize his dream: to make the National Park Service the federal arm for historic preservation as well as environmental conservation. This is the fascinating tale that follows.

Frederick L. Rath, Jr., was the first director of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president of the United States in November of 1932, a cold wind blew through Washington, D.C. This was not going to be just a change in administration, it was going to be a revolution. We who worked in the higher echelons of the federal government knew that new people, new philosophies and new operations were going to grip the reins of administration, and change was inevitable.

We of the National Park Service did not fear for our jobs. We almost took it for granted that the top-level officials, including myself, would be replaced. We were deeply afraid of who these incoming people might be, for they might have a totally different philosophy about our service. Above all we were apprehensive about who would be the new secretary of the interior.

From the time I had entered the Department of the Interior in 1913, conservation-minded secretaries had been the rule, some better than others, but none had been bad. Now, in 1933, we heard from all quarters that the president-elect was going to choose someone from the old Progressive party of Theodore Roosevelt and we hoped therefore it would be someone sympathetic to the conservation goals of the Park Service.

The first man offered the position was Bronson Cutting, former governor of New Mexico. When he was mulling over the offer, Harold Ickes, another ex-Bull Mooser, came to Washington from Chicago to try for the appointment of commissioner of Indian affairs. He and his wife had long been interested in Indians, having a vacation home near Gallup, New Mexico. Learning that several other people were favored over him for the Indian affairs job, Ickes was about to go home when his old friend, Senator Hiram Johnson, Republican of California, told him Cutting had turned down the Interior Department offer. Johnson suggested he try for that, and shortly thereafter Ickes was selected—much to his surprise.

|

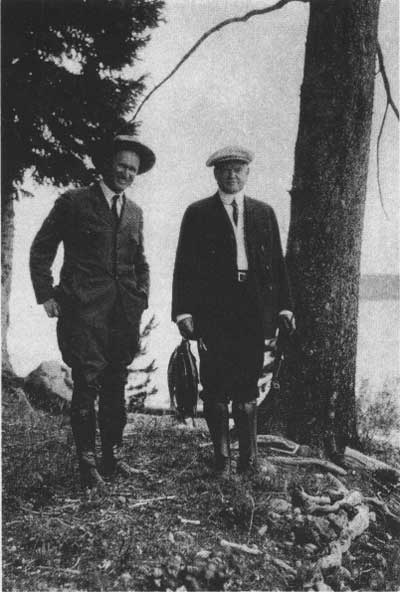

| Harold Ickes was once described as "a

prodigious bureaucrat with the soul of a meat ax and the mind of a

commissar." It was up to Horace Albright to convince the formidable

secretary of the interior of the need for an expanded National Park

Service. Courtesy, NPS History Collection. |

Just before Roosevelt's inauguration on March 4, 1933, I was told of this choice. A few days later Joe Dixon, assistant secretary of the interior in Hoover's administration and another Progressive, called me up to his office. When I walked in, I was introduced to "the new secretary of the interior, Harold Ickes."

From the start he was most cordial, saying, "There's no reason for you to remember me, but, in the early 'twenties, I went to Yellowstone National Park with Howard Eaton on a horseback trip. You made a speech one night to our group, and I was very impressed with you." And to back that up, a few days later he called me from his home in Winnetka, Illinois, to tell me that he wanted me to remain as director—and my staff to stay on as well.

When Ickes officially assumed command of the Interior Department, he made me an unofficial assistant. He had me become involved in the activities of appointed assistant secretaries and bureau chiefs (with a few exceptions), discuss matters with them, get memos and files from them and then talk problems over with him. I'll never know why he liked me and trusted me. He was a tough fellow to get along with, bad-tempered and irascible, but I always spoke up, though tempering my words according to his mood. Someone once said he was a "prodigious bureaucrat with the soul of a meat ax and the mind of a commissar."

In the few months I served under him, before my resignation in August 1933, I accomplished a great deal through this friendship. Most of this was done, not in the office, but on a series of weekend trips we took together.

Mrs. Ickes was a Republican member of the Illinois state legislature, so the secretary was lonely and began asking me to join him in off-duty hours. We spent a great deal of time together. This gave me the chance to get to know him well and to promote my philosophy on conservation and preservation, not only for the National Park Service and other bureaus in his department, but well beyond this area. Roosevelt had put him in charge of the Works Progress Administration and, with other cabinet members, the Civilian Conservation Corps. Ickes, in turn, made me his representative on these boards, so I had a chance to penetrate them with my ideas.

Ickes Trip I: March 26, 1933

Less than three weeks after Roosevelt's inauguration, Secretary Ickes called me up to his office on a Saturday morning—yes, we worked on Saturdays in those days! He said he really didn't know much about Washington, and, as long as he was going to stay around for awhile, he'd like to find out more about the capital city and its environs. I suggested that if he would like, we could take some rides on weekends. "Let's go tomorrow!," he replied.

So at 8 a.m., Sunday, March 26, 1933, a chauffeured Packard limousine arrived at my home on Indian Lane in Spring Valley in northwest Washington, not far from the Maryland-Virginia border and the Potomac River. It was a rather unpleasant day, cold, windy, and overcast. That didn't bother me, but the first thing Ickes said to me did. It was that we had to go pick up Senator Hiram Johnson who was going to join us. I wasn't too happy about this. I had imagined having the secretary alone all day to get in my thoughts and plans for the National Park Service, a little propaganda and policy talk. And anyway Johnson was just about as disagreeable a personality as I had heard Ickes was—"birds of a feather," I thought.

Senator Johnson lived on the opposite side of town, not far from the Capitol. Instead of heading "as the crow flies," I instructed the driver to skirt the perimeter of Washington to inspect a few historic sites on the way. I explained to Ickes that when Pierre Charles L'Enfant designed the federal city, under the direction of George Washington, he included many park areas, among them the Mall, Capitol, and White House grounds, etc. These National Capital Parks, spreading out to the environs of the city, had grown to about 600 reservations, with the addition of natural sites like Rock Creek Park and the Potomac parks. Although they were administered by the Interior Department for a short time from 1849 to 1867, they had been under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ever since. I had been trying to get ahold of them for the Park Service—with no luck so far. I let Ickes know all about this and my reasons for feeling they should be in my bureau, in his department.

Included in the Capital Parks were the remainders of a ring of forts that had formed a 37-mile circuit of defense around Washington. There were 50 of them, strategically located to protect the city during the Civil War. Ickes was very interested in these and wanted to see some of them, so I had the chauffeur drive us up Nebraska Avenue to Wisconsin Avenue where Fort Reno was located, thence across Rock Creek Park to the 7th Street Road [Georgia Avenue] and Fort Stevens. When we got there, we walked up to the old fortifications, still very visible. As we covered this area I explained to Ickes the situation in 1864 when General Lee and most of the Army of Northern Virginia were fighting for their lives to defend Richmond from the grim push by the Army of the Potomac. The Confederates had to try to divert the Union Army. Their information indicated that Grant had lost almost half his troops. Every available man had been rounded up and sent to replace these casualties, leaving Washington almost defenseless. Thus General Jubal Early decided to make a surprise attack on Washington from the north. On July 6th the Confederates were on their way, crossing the Potomac everywhere from Harpers Ferry to Muddy Branch, 20 miles from Washington. On July 11th, the Rebels advanced down the Rockville Road [Wisconsin Avenue] closing in on forts Slocum and De Russy. Next reports came that more columns were heading down the 7th Street Road toward Fort Stevens, which was manned by only 209 men. Telegraph lines from the north into the capital were cut. The railroad tracks to Baltimore were torn up by Confederate cavalry.

|

| Fort Stevens, visited

by Albright and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes in 933, was

partially restored by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930s.

The workers seen here are rebuilding the western portion of the fort's

parapet. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. |

For complacent Washington it was suddenly a desperate situation. Frantic calls went out to Grant, and he sent the entire 6th Corps, but it took two days to get it there. In the meantime, teamsters, government clerks, convalescing soldiers—anyone who could hold a gun—were issued arms and rushed to the forts around the city, mostly in the northern corner. Strangely, the Confederates didn't throw their full strength into the attack. After a moderately fought battle, Early's orderly retreat back into Virginia marked an end to Confederate threats against the capital.

However, during the battle, the civilian population came in droves to watch the action. Even President Lincoln, stovepipe hat and all, spent part of both days clearly visible on the parapets of Fort Stevens. It was an extremely dangerous thing to do as exemplified by the fact that a surgeon was killed by a sharpshooter only three feet from Lincoln. At first the president was politely asked to get down from the parapet, then scolded and finally ordered to leave, which he reluctantly did. History said the commanding general, Horatio Wright, did the ordering. A more romantic version said a young lieutenant colonel (later associate justice of the Supreme Court) Oliver Wendell Holmes shouted at his commander-in-chief, "Get down, you fool!"

We were already about a half hour late to pick up Senator Johnson, so we quit sightseeing and quickly covered the five or so miles to Johnson's apartment. He was standing outside on the sidewalk. As he climbed into the car he grumbled that he had been waiting "an eternity." He added, "Go any place you want to, but get us back by dinnertime. Mrs. Johnson keeps a pretty close schedule."

Ickes told me to cover anything I wanted, but said, "We'd rather see less and learn more, so don't take in too much." In view of all these instructions, I made some quick recalculations, eliminating a tour of Harpers Ferry and Great Falls.

We sped through the downtown area, around the Tidal Basin and across the Potomac River on the 14th Street (or Highway) Bridge to Virginia. Our destination was Wakefield, the site of George Washington's birthplace, which was located about 80 miles away on Popes Creek, down the neck of land separating the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers.

The actual house in which Washington was born had burned on Christmas day, 1779. The family moved away, leaving the ruins. No accurate records of it remained, and no one bothered to note the birthplace until 1815, when George Washington Parke Custis (grandson of Martha Washington) visited Popes Creek. In a moving ceremony commemorating Washington's birth, he placed a stone on the site where he considered the house to have been. A century later, even that had disappeared.

In 1923 the Wakefield National Memorial Association was formed by Mrs. Josephine Wheelwright Rust. The object of this group was to restore the plantation for the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington in 1932. The War Department held a small piece of land with a monument on it. Mrs. Rust prevailed upon John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to put up $110,000 to buy an additional 400 acres. She entered into an agreement with him to match that sum by January 7, 1931, for construction of the birthplace. Fairly soon she realized she couldn't make the dead line, so she came to me for advice and help. I immediately sensed an opportunity to enter the National Park Service in the historical field, a dream of mine for years. I discussed the problem with Representative Louis Cramton, Republican of Michigan. He succeeded in getting a bill through Congress to create the George Washington Birthplace National Monument, operated by the National Park Service; to have the War Department relinquish the claim to their land; and to appropriate money to build Wakefield. Rockefeller forgave the matching sum agreement now that the Park Service owned the property.

|

| Eighteenth-century costumes and a military

band enliven the June 14. 1932, dedication of Wakefield, a

reinterpretation of George Washington's birthplace. Secretary of the

Interior Ray Lyman addresses the crowd as National Park Service Director

Horace Albright looks on from the doorway. The young girl in colonial

dress to Lyman's left is Albright's daughter, Marian. Courtesy NPS

History Collection. |

We were now faced with a real problem because we found that the site of the original house was probably not where George Washington Parke Custis had stated it was. Mrs. Rust and her experts insisted it was by the War Department memorial. Our people disputed this when they discovered foundations of a large structure nearby. I had to make a decision to either stop work indefinitely until positive identification could be made or proceed to complete the building for the target date in 1932.

In those days historical preservation was new, Williamsburg experts having about the only knowledge in this budding field. My sense of history told me to hold back, but my urgency to get the Park Service acknowledged as a viable operator of historic sites (as well as being able to remove something from the War Department) caused me to allow the Wakefield construction to continue. My basic point was that we would never know what the original looked like. However, we always made a point that our Wakefield was not intended to be an identical copy of the original—just a memorial to George Washington. I did insist, however, that every move that was made here would be checked by the Commission of Fine Arts and Mrs. Rust's organization, and that the house would be an authentic example of an upper-class, tidewater Virginia plantation of that era. We even arranged with Colonial Williamsburg to have their artisans, such as brick-makers, etc., do the work at Wakefield. The federal government paid for the construction, and the Memorial Association turned over all their holdings to us on June 22, 1931. The 200th anniversary won out over research. And I should add that the foundations we found (and had not built upon) proved to be the authentic ones. However, the Wakefield memorial was built and furnished, the grounds and gardens renewed, and the cemetery restored to its 18th-century appearance—all finished for the George Washington Bicentennial in 1932.

When we arrived at Popes Creek, everything seemed to go well. Ickes and Johnson were fascinated with the work on the house as well as the beautiful landscape architecture work being done by our National Park Service staff. It seemed to surprise the secretary that we had professionals in many fields in our department. Ickes especially enjoyed a conversation with a ranger who was a descendent of one of George Washington's half-brothers.

|

| Horace Albright (left) and Fine Arts

Commission members survey the Washington family graveyard at Wakefield.

Albright insisted that the commission approve every stage of the

Wakefield reinterpretation. Courtesy. NPS History

Collection. |

On the way back to Washington, I saw that we had a little extra time, so I suggested that we have a quick tour of Fredericksburg, Virginia. We covered sites touching on the life of George Washington—his mother's home and next to it, Kenmore, the estate of his sister, Betty Fielding, whose son married Martha Washington's granddaughter. We also saw James Monroe's law office. We made a detour to Ferry Farm, across the Rappahannock River, where Washington lived as a boy before moving to Fredericksburg. It was here that the legendary act of chopping down the cherry tree was supposed to have occurred. We took a cursory look at the Fredericksburg battlefield as it was right along the river in town, but had to pass up the other great Civil War battlefields nearby as the deadline for the Johnsons' dinner with Ickes was approaching. No more stops were made until we reached Washington and my companions were dropped off at the Johnson apartment while I was chauffeured to my home.

Ickes Trip II: April 2, 1933

My second trip with Secretary Harold Ickes, in his government limousine, was on a beautiful spring day, April 2, 1933. Unfortunately, we had to take Senator Hiram Johnson along again. His wife had expressed an interest in seeing historic and scenic locales in northern Virginia, so she was joining us, too.

On the way to Johnson's apartment, Ickes told me I had gotten Johnson very interested in Virginia history on the March 26th trip, especially in the role of the National Park Service. He thought a powerful ally like that in the Senate would be a real asset to me. I felt I had to tell him that while the senator had supported parks and preservation while governor of California and had never opposed national park legislation in the Congress, he had never lifted a finger to help us, either, as far as I could remember, although he had been in the University of California (class of '88) with both Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane and Park Director Stephen Mather. Hiram Johnson had many things on his mind but parks were not a high priority item.

In spite of this, it seemed like a fine day ahead as we four set off in the roomy limousine, the Johnsons and Ickes comfortably seated in the back and I on one "jump seat" behind the driver with my maps and pamphlets spread out on the adjacent one. I explained my plans for the trip, pointing out the routes, etc., and received their approval before we started.

We drove around the Capitol grounds to the Mall and followed it to the Lincoln Memorial, crossing the Potomac on the recently completed Arlington Memorial Bridge. As a member of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, I fancied myself a fine tour guide, sketching the scenic and historic features of the city as we went along. I made a particular point of having them see Roosevelt Island, a large, forested tract of land that had once been a farm, located in the Potomac River between the Key and Arlington Memorial bridges. It had been given to the government by the Roosevelt Memorial Association in December of 1932.

Reaching Virginia we headed down Route 211, the Lee Highway, past Warrenton, where we turned off to Culpeper. From here we followed the so-called lowland route until crossing over a ridge into the upper Rapidan and following this valley to Hoover's camp.

While Herbert Hoover was president, the commonwealth of Virginia and interested private individuals had offered to buy land and construct buildings on it for his use, to create for him a forested retreat on the Rapidan River headwaters in Virginia. He refused, and instead used his own funds to purchase the land at five dollars an acre to build this so-called camp on it. It was inside the boundaries laid out for Shenandoah National Park. Virginia had committed itself to buy all lands to be included in this new park. In January 1933, before leaving office, Hoover generously donated his thousand-acre Rapidan property to Virginia (which later was included in that state's gift to the National Park Service). He hoped that future presidents would derive as much pleasure from the tranquility of this beautiful land as he had. It turned out quite differently, for those who followed him as president rarely used it. Roosevelt couldn't because of his paralytic condition, so he constructed his own retreat at Catoctin in Maryland, naming it "Shangri-la" (now Camp David), and that became the favorite hide away for succeeding chiefs of state.

|

| Horace Albright was instrumental in selecting

the 1,000-acre site for Herbert Hoover's camp (right) on the Rapidan

River in Virginia, which Hoover subsequently gave to the nation for the

enjoyment of his successors. Roosevelt's physical impairment, however,

prohibited his use of the rugged camp, and he constructed his own

retreat in Maryland, "Shangri-la," now Camp David. Courtesy, NPS History

Collection. |

At the time of our visit, the land acquisition for the park, as required by Congress, had nearly been completed by the commonwealth of Virginia, but the reality of turning it over to the United States was close enough for the National Park Service to cooperate in its supervision as well as planning for its future. It was still guarded by a few men of the Marine Corps, and I kept a set of keys to it.

There was no more beautiful site in Virginia than this camp lying at the confluence of the Mill Prong and Laurel Prong of the Rapidan River. It was deeply wooded, only enough trees being cut to lay out the rustic cabins on the forested floor. Mrs. Hoover had supervised the felling of each tree, wishing to keep the whole area as close to its natural state as possible. As we walked along the paths by the rushing stream, I explained the layout of the cabins, where the horseback trails led, and then showed them the favorite fishing pools where Hoover so enjoyed relaxing at his favorite sport. Ickes and Johnson exchanged some disparaging remarks about the ex-president. Johnson's dislike, even hatred, was very evident although Ickes' rejoinders, I thought, were somewhat milder. In 1920, when it appeared that any Republican could win the presidential election, Johnson had fancied himself as the candidate. He had been defeated for vice-president in 1912 when he ran with Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt having died in 1919, the way for the presidency was cleared for Johnson. However, Herbert Hoover entered the California primary, following his nationwide acclaim for the humanitarian causes to which he had devoted himself during World War I. He gave Johnson a real run in California, and, although Johnson beat him in the primary and lost the nomination to Harding at the Republican convention, he never forgot or forgave him. And he hated Hoover the rest of his life.

|

| Albright accompanied Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover on a

successful fishing trip in 1927. Hoover's love of outdoor sport inspired

his creation of a presidential retreat on the Rapidan River, with

Albright's help. Courtesy, NPS History Collection. |

At one point in our walk around the camp, I noted a cottage where Hoover and Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald of England had reached an agreement to reduce and limit warships and other naval property. Now as we strolled along the river, Johnson kept peering into the little, black ponds and saying he was looking for parts of our navy that Hoover had sunk! At one place he exclaimed, "I see one of our warships. I think it is the Lexington." Of course, I thought such a performance was crude and shameful, kept my head averted, and said nothing. Ickes smiled but also remained silent while Mrs. Johnson, without a word, immediately walked back to the car.

Johnson soon grew tired of the quiet river scene and suggested that we get on to the Skyline Drive, which was currently being built along the summit of the Blue Ridge Mountains from Front Royal to Thornton Gap. As we climbed back up the trail to the car, Ickes suddenly noticed an area with trees cut down and demanded to know what "that monstrosity" was. I called a Marine guard over and inquired. [The Marines kept a camp nearby to provide security for the president.] He explained that when Hoover was here it had been forbidden to cut any trees except those which were dead or fallen. But in the last few months the Marines had been cutting standing ones for firewood. Thunder rolled across Ickes's face and he roared, "I am the secretary of the interior and in charge of this property. There will be no more devastation of these surroundings by ruthlessly cutting trees. Hear me?"

Before we left the Rapidan, I made a point of telling Ickes and Johnson about how that scenic road came to be built and Hoover's contribution to it. It was in May 1931, when President and Mrs. Hoover invited a group of bureau chiefs from the Interior Department to spend the weekend with them at the Rapidan retreat. My wife, Grace, and I were included. The first night we were there the president suggested we all join him the next morning for a horseback ride. When the time came, no one showed up except Hoover, his wife, Lou, his personal aide, Larry Richey, and me—and, of course, the ever-present Secret Service. We rode slowly to the summit of the Blue Ridge Mountains and then along the east side. The president, ever the engineer, told me that he thought the trail was a perfect route for a scenic drive that could be world famous. He suggested I get it surveyed and, if found feasible, have the building begun promptly. He felt funds available to ease problems of the Depression could be utilized to employ impoverished farmers in the drought-stricken Shenandoah Valley. They could use their own tools and equipment, live at home, and still be able to work their farms while being paid to construct the parkway. It was a wonderful plan, and we carried it out as Hoover envisioned it. And more so! The original surveys called for a road through the Marine Corps camp area adjacent to Hoover's camp to Big Meadows and then to Thornton Gap. Before that was half-way done, the road was extended the entire length of Shenandoah Park. And eventually the idea was adopted to connect the Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains national parks, resulting in over 450 miles of magnificent scenic highway. Now in 1933, only a short section of about 15 miles to Panorama Pass and the Lee Highway was finished. It was not paved, only graded with beautiful stone parapets built at areas of dangerous dropoffs. As we drove along this breath-taking road, Johnson and Ickes went so far as to praise the standards of the highway construction, but if Hoover was ever praised for his part in the project, the kind words did not reach my ears.

We dropped down off the Skyline Drive project to the Shenandoah Valley and headed for Luray, Virginia. However, I thought these two rather gloomy personages could do with a little fun as well as enjoy a magnificent panorama, so I suggested we make a detour up to "Skyland" on the summit of Stony Man Mountain. This resort was owned and operated by George Freeman Pollock, one of the moving spirits behind the drive to create Shenandoah National Park. He also was a real character! He woke his guests in the morning with a bugle blast and "picked" them up at the end of a long, strenuous day with local corn whiskey called "Mountain Dew." He loved rattlesnakes, collected them in bags, and then dropped them in the middle of the floor after he was sure all his guests were present! It was probably fortunate that we found Pollock absent from "Skyland" when we showed up. I'm not sure how Ickes and Johnson might have taken it if he'd pulled one of his stunts on them. My career in the National Park Service might have ended right there!

|

| George Freeman Pollock (right), owner of the mountain resort

"Skyland," relaxes with James R. Lassiter, superintendent of Shenandoah

National Park. Pollock, known for his colorful antics, frequently

startled hotel guests by dropping a bag full of live rattlesnakes on the

resort lobby's floor. Courtesy, NPS History Collection. |

After lunch we drove to Winchester, the oldest town west of the Blue Ridge, where George Washington began his career as a surveyor. Of course, its greatest fame rose from being the center of strategic Civil War history, including the headquarters of "Stonewall" Jackson and the famous "Sheridan's Ride" from Winchester to nearby Cedar Creek, where the Union troops broke Jubal Early's Shenandoah army. This, combined with Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Lincoln's reelection, and Grant's siege of Richmond, finally ended the War Between the States. Everyone became so interested in this Shenandoah campaign that we followed the battle lines carefully as I read from a Virginia historical marker book.

We thought of going on to Harpers Ferry but decided to cross over to Riverton to get a glimpse of the famous apple orchard of Senator Harry F. Byrd and the vast pasture the Army cavalry used for its currently "unemployed" horses—a really great "horse farm." We made no more stops but continued to the Blue Ridge Pass at Panorama. Then we turned eastward to the Lee Highway and on to Washington, with only a brief stop at Manassas for me to describe the action at the two battles of Bull Run during the Civil War.

For most of the time since the Rapidan Camp visit, Ickes and Johnson had seemed as contented as was possible for them. Johnson had temporarily forgotten to mount attacks on Hoover. However, something at Manassas brought Harry Chandler, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, to his mind. And he had an inexhaustible supply of hatred and invective for the newspaper executive. Ickes, Mrs. Johnson, and I sat in silence while he raved on until we pulled up at the Johnson apartment about 8 o'clock. Ickes got out here to join them for dinner. I was "chauffeured" home, grateful for the soft back seat and silence!

Ickes Trip III: April 9, 1933

On April 7, 1933 I received instructions from Colonel Bill Starling, chief of the White House Secret Service detail, to be at the south entrance of the White House at 9 a.m. on Sunday, April 9th. I was to go with President and Mrs. Roosevelt and others to see Hoover's camp on the headwaters of the Rapidan River in Virginia.

I was very surprised and honored to receive this invitation. My acquaintance with Franklin Roosevelt, prior to his becoming president, was rather limited. We had marched in the same Defense Day parade in Washington in 1916, Roosevelt being the grand marshal of it. I had seen him at various Washington social events during those war years. The time I remember best was a small dinner party at Adolph Miller's home. It always stuck in my memory because Roosevelt brought a stunning-looking woman to it instead of his wife, and it was obvious to the casual observer that they were quite fond of each other. (A few years ago when F.D.R.'s love affair with Lucy Mercer was revealed in a magazine article, I instantly recognized the lady from the dinner party.)

In 1931 I saw Roosevelt several times in Salt Lake City at the Governors' Conference. It was there that he asked me to take his son, Franklin, Jr., on the trip to Zion, Grand Canyon, and Bryce Canyon national parks where most of the other governors and their wives were going, but he couldn't because of his paralyzed legs. We did take the boy with us and got along all right with him. His father had told me to put him on the first bus leaving for Salt Lake City if he disobeyed us in the slightest.

The next time I was with Roosevelt was in October 1931, on the speakers' platform at the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebration. The governors of the 13 original states attended, Roosevelt being the most impressive governor there—as well as being regarded as the next president of the United States. After delivering his address, he was mobbed by people, especially the press. I had noticed that before he could be seated the braces on his legs had to be unlocked. Now, as he prepared to leave, I also noticed that no one had remembered to lock those braces again. Acting as though I had dropped something, I quietly got down and secured them—in my high silk hat, striped trousers, and long-tailed morning coat!

Now on this lovely April morning in 1933, I arrived at the White House somewhat early, and my car was taken by a guard and parked. A motorcade was being formed for the trip to the Rapidan. Mrs. Roosevelt was to lead the procession of cars, driving a new blue Buick roadster, with the president seated beside her and their son, John, and a Secret Service agent crowded together in the rumble seat. Two motorcycles carrying Secret Service officers were to precede the line of cars. Immediately behind Mrs. Roosevelt's car was an open sedan carrying Secret Service officers. The third in line was a large touring car with the president's confidant, Louis Howe, the Henry Morganthaus, and Mrs. Elliott Roosevelt. The fourth car was another open touring car. I was taken to this car by Colonel Starling and told to sit in the rear seat between two ladies to whom I was formally introduced. They were Miss Marguerite "Missy" Le Hand and Miss Grace Tully, the president's private secretaries. Little did I know at this time what power they held with the president, especially the close relationship Miss Le Hand enjoyed with him! However, at the moment, I looked around and saw Secretary Ickes join the procession with his official car, his black Packard limousine, the same that I had been traveling in recently.

I quickly stepped out of the car with the ladies and went to speak to my chief. Colonel Starling shouted at me to stay where I was, but I disregarded him and went over to Ickes who immediately assumed I would ride with him. I said Starling had assigned me otherwise, but I would ask his permission to switch cars. Even though Starling and I had been friends since the days when presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge had made visits to Yellowstone National Park, he eyed me coldly and said the schedule had been arranged and I should not try to change it. I climbed in my appointed car and sat down between the two ladies, but they were busy talking across me to each other. So I decided to ignore orders and go for the opportunity to discuss National Park Service problems with Ickes, undisturbed, for several hours, a rare opportunity. I excused myself from the ladies and headed for Ickes's car. Starling noticed my move and again gave me a stern warning that if I didn't do as he said, he would never try to help me again. Ickes growled, "Forget the old buzzard. He's power-mad."

I smiled and climbed into the secretary's car, riding with him all the way to the Rapidan Camp. As it was the same route we had taken a week ago, he did not have to pay too much attention to sightseeing. Consequently we had a fine discussion of national park affairs about which I wanted him to be informed.

It was a beautiful day, mild and sunny with dogwood, redbud, and other flowering trees in bloom, as well as masses of wildflowers in the fields and along the country roads. The entourage drove quickly along the Lee Highway to Culpeper and on to Hoover's Rapidan camp. Arriving at the forested retreat, we immediately encountered the difficulty that would prove insurmountable if Roosevelt were to use this lovely place. When the president got out of the roadster to walk to the main house in the camp complex, he quickly found the ground too uneven and rough for his weak legs, even with braces on them. So the strongest of the Secret Service agents and I simply picked the president up and carried him to the spacious porch of the main house where everyone settled on chairs, steps, or whatever was available.

Mrs. Roosevelt had brought along an elaborate picnic lunch, which we ate outside, enjoying the beautiful rushing water of the Rapidan and the lush spring green of the forest. She was ever so charming, natural, and friendly, a lovely hostess who didn't even sit down to eat until everyone, including Secret Service and Marine corpsmen, was accommodated with full plates and cool beverages. Will Carson of the Virginia Conservation Commission, who had done the most to insure the formation of the Shenandoah National Park, had been invited to join the president to inform him about the new park as well as other Virginia conservation projects.

I couldn't help comparing this day with others I had spent here when Hoover had been president. Today everything was lively, lots of good-natured banter, informal conversation, and laughter, even kidding the president himself. With the Hoovers it had been much more formal with intellectual, scholarly discussions and an opportunity for those present to express their opinions on whatever was under discussion or to initiate their own subject.

At one point Roosevelt turned to me and said, "Mr. Albright, I'm sure we all would like to hear you give us the history of the Rapidan Camp."

I gave a quick background of facts, treading lightly about the Hoovers but praising them for their construction of the camp and their gift of it to the American people.

When I finished, Colonel Starling said, "Come on, Albright, tell about our part in this."

And, at the president's insistence, I did. Shortly after Hoover's inauguration and decision to build a retreat for himself and future chief executives, I was asked to join a group of four men to locate the "perfect spot for beauty and good fishing." Larry Richey, Hoover's aide and best friend, Henry O'Malley, commissioner of fisheries, Colonel Bill Starling, chief of the White House Secret Service, and I comprised the "discovery" group. Hoover had laid out the basic necessities: the camp had to be within 100 miles of Washington, on a stream with good fishing (Hoover's favorite outdoor sport), and in a forested, serene setting for hiking and horseback riding, enjoyed together by the Hoovers. We covered promising sites from the foothills of the Blue Ridge to many miles down the Potomac east of Washington, even considering the area where Camp David was eventually built. At last we picked this lovely Blue Ridge Mountain setting, and President Hoover personally purchased a thousand acres just within the proposed boundaries of Shenandoah National Park.

When I finished, Roosevelt thanked me, but then Starling broke in to say, "Yes, Director Albright arranged it all. He led us a merry chase all over Virginia and Maryland, knowing all the time that we would make the right decision, according to him—a spot in a national park!"

After lunch, Roosevelt suggested that he'd like to get going to see the park and the Skyline Drive, so we all headed for the cars. There were major changes in the seating arrangements for the return trip. Louis Howe joined Mrs. Roosevelt in the roadster while the president chose a seven-passenger, open touring car. He called me over and said that, on the way back to Washington, he wanted me to ride with him. So the president and the driver were in the front seat, Henry Morgenthau, then head of the Farm Credit Bureau and later secretary of the treasury, and two other men (I was so excited at the time that I never did remember who the other two were) in the back seat and a Secret Service man and myself on the "jump seats." I was directly behind the president.

Leaving the Hoover camp, we drove up an old wagon road through the Marine Corps area to the unfinished Skyline Drive. It was a beautiful road, which swung under the peaks but was generally right on the summit backbone of the Blue Ridge with spectacular views both into the Shenandoah Valley and the Piedmont country. No one, including the president, seemed to mind that we soon looked rather ghostly with our covering of good old Appalachian dust. Roosevelt asked me about the establishment of the National Park Service and its policies relative to the Eastern parks, generally, and Shenandoah and the Skyline Drive, in particular. He was interested in conservation but had never been very active in it. Aside from stuffing birds as a child and being chairman of the Fish and Game Committee of the New York State Senate, I don't know of any real effort on his part to be involved in conservation before becoming president.

|

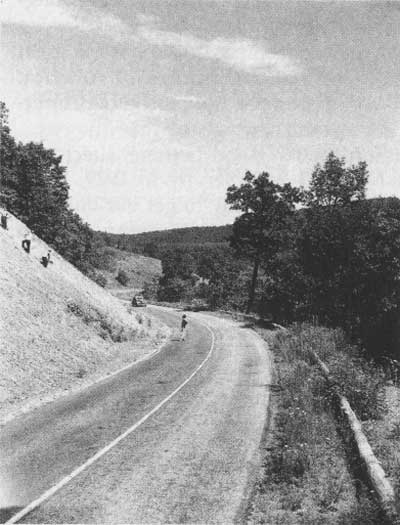

| Carving a major thoroughfare from the side of the Blue Ridge

Mountains involved considerable feats of engineering. Here the Civilian

Conservation Corps covers a loose embankment on the Skyline Drive with

seed hay to prevent landslides in the late 1930s. Courtesy, NPS History

Collection. |

Roosevelt seemed surprised to learn that the Skyline Drive was being built by impoverished local farmers who were paid with relief funds Hoover had secured from Congress. He commented favorably on the alignment of the highway, the beauty of the route, and the hand-built embankments at the panoramic overlooks. He sized up the standards of the road very quickly. Turning to me he said, "Albright, the super-elevation on that curve ahead must permit a speed of 45 miles an hour." (He was exactly right!) However, there was a constant dissenting voice from the back seat. At every stone barrier protecting an overlook, Morgenthau criticized the work and blamed Hoover for spending too much money on it, never stopping to think that they were built by competent stonemasons out of work until employed on the project.

Finally, the president obviously had listened to one too many of these harangues, for when Morgenthau started another, Roosevelt turned and said sharply, "Oh, shut up, Henry! If it were not for these protective walls you would get out and walk. You are the scariest one in the crowd." That was the last we heard from Morgenthau for the rest of the day!

|

| This view looking north along the Blue Ridge was typical of the new

vistas opened to travellers by the construction of Skyline Drive in the

1930s. George Pollock's Skyland, a highlight of Albright's second trip

with Harold Ickes, is to the right. Courtesy, NPS History

Collection. |

We left the park area at Panorama, and went down the Lee Highway toward Washington. As we approached the Rappahannock River, I thought the opportunity had come for me to spell out to the president my deep conviction and long-standing dream of a National Park Service that would encompass not only the great scenic and natural features of America, but would preserve and protect her cultural and historic heritage as well.

Shortly after I had become director of the National Park Service in 1929, I had seized an opportunity to get our bureau's foot in the door of historic preservation, in which I had been deeply interested for years. The Park Service had always been identified with natural areas, mainly in the far West, although we already held many sites of prehistoric Indian culture as well as features of western history, such as the military fort in Yellowstone. But I had always wanted to branch out to gather in Eastern historic sites, battlefields, and areas of natural beauty—not only for their intrinsic value, but because I felt that if the entire country were represented, if it were truly a National Park Service, we would have more financial aid and congressional support.

The Wakefield restoration project was our first opportunity in the field of historic preservation. Shortly after Wakefield's completion in 1932, the idea for a national park encompassing Williamsburg, Yorktown, and Jamestown on the peninsula bounded by the York and the James rivers in Virginia took shape. This would become Colonial Historical Park, with the three areas connected by the beautiful Colonial Parkway (although Williamsburg always remained independent).

Keeping this in mind, I initiated the conversation by asking Roosevelt if he remembered that the Second Battle of Bull Run began in this vicinity and ran miles down to the town of Manassas, with the Union Army suffering a serious defeat. From this I went on to discuss various other battlefields and historic parks and my ideas about incorporating them in the Park Service.

He listened carefully for some time and then asked, "Well, this is all Civil War. What about Saratoga Battlefield in New York? What about the Revolutionary War?" He said that, as governor of New York, he had asked that Saratoga be made a state park, but nothing had ever been done. I told him that President Hoover, in December 1931, had submitted his recommendation to have Saratoga designated a military park, but this had died in congressional committee. I said that I was not just suggesting battlefields being added for National Park Service protection, but historic buildings and other sites that Americans should know, treasure, and preserve. He asked no more information of me, simply said I was right and that all this should be done immediately!

I was thunderstruck and speechless as he laughingly ordered me, "Get busy. Suppose you do something tomorrow about this!"

I said that I was not just suggesting battlefields being added for National Park Service protection, but historic buildings and other sites that Americans should know, treasure, and preserve. . . . I was thunderstruck and speechless as [the president] laughingly ordered me, "Get busy. Suppose you do something tomorrow about this!"

We were soon approaching Washington. It was getting dark, beginning to rain and traffic was slowing down considerably. Suddenly the entourage stopped. Secret Service agents surrounded our car while we waited to find out what had happened. It turned out that Secretary Ickes's Packard had bumped a car that had attempted to cross into the presidential cavalcade near Falls Church. Two crushed fenders were the only casualties, so shortly thereafter we picked up speed and turned into the White House grounds about 6:30 p.m.

As I got out of the car at the White House, I thanked the president from the bottom of my heart for the privilege he had given me to express my hopes and dreams and for the gift of being able to carry them out. He gripped my arm and said, "Albright, I think you deserve this opportunity. Go to it!"

The article in the New York Times of April 10, 1933, stated: "About an hour after the Chief Executive had settled back into the White House, all major newspaper offices and press associations were connected simultaneously with the executive office switchboard, but the announcement that came forth said only that the trip had been made and that it was 'uneventful.'" For me that was one of the understatements of my lifetime. On that one day, the historic heritage of America had been safely placed in our bureau's care, and my dreams had become reality. At last we had a real National Park Service, stretching from one ocean to the other and from Canada to Mexico, covering the whole range of conservation and historic preservation.

|

| An enthusiastic crowd greets President Roosevelt and his entourage at

the opening day ceremonies for Shenandoah National Park, July 3, 1936.

Here FDR enjoys an exchange with Governor George Campbell Peery of

Virginia. Courtesy, NPS History Collection. |

Ickes Trip IV: April 23, 1933

Secretary Ickes and I had planned a tour of Annapolis, Baltimore, Fort McHenry, Antietam, and Harpers Ferry, for April 23rd. Engagements came up for both of us that we couldn't ignore. He had a summons to see Louis Howe in the morning, and I found I was expected to attend the California congressional reception at Clarence F. Lea's apartment sometime between 4 and 6 p.m. to present my case for the creation of the Kings Canyon National Park.

So the secretary and I started out a little earlier than usual, leaving my house about 8 a.m. This time our route followed Canal Road upstream alongside the Potomac River and the old Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to the Chain Bridge. This was one of my favorite areas around Washington. When I first came to the capital in 1913, I had spent many hours tramping up the canal toward Great Falls.

I think I caught Ickes's attention right away when I told him that George Washington had originated the whole scheme for use of the Potomac River, that he had pushed through an agreement for the building of a series of canals by the Patowmack Company and was its first president. He had been afraid the Spanish or British would lure all the business of the new settlers out beyond the Appalachian mountains. Hence he wanted to make the Potomac a commercial waterway and did. The company he started operated from 1788 to 1830 when the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Company superseded it.

When we got to Great Falls, about ten miles upriver from Washington, we tramped around the remains of the five giant locks built by the Patowmack Company that were needed to get past the awesome 77-foot drop in the river cascades. It must have been a tremendous operation in its day. Beside the transporting of goods, the waters of the later C&O Canal powered grist mills, and other business operations. Ickes seemed fascinated by the history of the canals and said, "I'm going to get these." He not only got them for the Park Service a few years later, but he had sections of the C&O Canal restored, refilled with water, and towpaths cleared. In 1969, an impressive site a few miles below the falls was named Mather Gorge in honor of the first director of the National Park Service.

This conversation led us into a discussion of where our new power to acquire historic and military areas would lead. Ickes and I had been astounded at the proposal we had received from the White House after our April 9th trip with the president. Not only were all the historic and military areas held by the federal government included, but the National Capital Parks and numerous national monuments in both the War and Agriculture departments were to be given over to us. The national cemeteries were even thrown in for good measure! I had gotten quite upset about this and told Ickes I would refuse this kind of deal.

He replied, "Albright, we'll take 'em all for now and get rid of the bastard ones we don't want later. Don't rock the boat!"

As it turned out, that's what we did. I did shed the cemeteries (except those directly attached to national battlefields) by talking to several of the highest-ranking Army and Navy officers, reminding them that we were not military people and could not be responsible for where men were buried—a private might get the spot next to a general, for example. Their hair almost stood on end at the very thought, strings were pulled, and that ended that problem.

Now as Ickes and I saw it, the greatest problem was going to be how to avoid having everything on earth dumped into the National Park Service. I reviewed a few of the areas that various congressmen and other politicians had tried to force upon us in the past, with a couple of bad ones like Platt and Sully's Hill national parks slipping by. I said, "Mr. Secretary, you'll have to keep an eye on this problem. The gates have been opened for politicians to want anything from a truly grand area that should be under your control to the alleged site of Hiawatha's grave."

"Yes, I know that" Ickes said, "but why do they do that?"

"Well, the more tourists they draw to their state, the more money rolls into the voters' pockets. But the politicians never seem to realize that every foot of a national park area has to have personnel to care for it, roads, sanitary facilities, water, and accommodations built and maintained. All of these cost a great deal of money. The same politicians are shocked when we have to go before them and beg for every dime. They don't give us proportionately more, so their appropriations are spread thinner and thinner."

We returned to the car and, as we rode along the river, we discussed the plans of the Reclamation Service for multiple dams on the Potomac. We both hated dams unless absolutely necessary for survival! Again I briefed him on the methods of battling reclamation projects, telling him of how lakes in Jackson's Hole, in the Bechler region, and in Yellowstone in Wyoming had been saved. He actually chuckled at our wily tactics and apparently never forgot them. Throughout his tenure as secretary, Ickes put up stubborn fights against many water projects.

Our road led us inland for some distance and then we emerged at Harpers Ferry, where the Potomac and the Shenandoah rivers meet and separate Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. This historic city was the scene of the raid by John Brown on the federal arsenal in October 1859. Brown intended to arm slaves and lead them in a revolt, but his plan backfired, resulting in Brown's arrest and execution by hanging. When I suggested Ickes might like to see the place where Brown was captured, he declined with a muttered, "Man was crazy. Don't care about him." Even though Harpers Ferry was an extremely picturesque town and an interesting, pivotal center of Civil War activities, I just couldn't interest the secretary in it. However, when I happened to mention that "Stonewall" Jackson had captured the town and over 12,000 Union troops on his way to Antietam, he instantly said, "Oh, is Antietam around here?" When I assured him it was only a few miles farther, he said he wanted to go there.

It is always difficult to visualize peaceful, pastoral Antietam as the battlefield where 25,000 men fell in a single day, the bloodiest of the Civil War. Because of our engagements in Washington we had little time to go over the battlefield carefully. But we did get out of the car and walk across the Burnside Bridge and the infamous Bloody Road, scenes of incredible slaughter. Ickes was strangely silent, halting now and then to gaze thoughtfully ahead. I was struck by the impact these scenes seemed to make on him. For all the years I knew him I rarely saw this softer side. Shortly thereafter we turned around and made a swift trip back to the capital.

This had been a day filled with interesting discussions with impact on the future little realized in 1933. However, it was memorable to me because, on the drive into Washington, I decided it was time to start breaking the news to the secretary that I intended to resign as director of the National Park Service. When he had asked me to remain as director, I had told him that I would for the present, but that I was considering leaving government service. Actually I had already accepted the position of vice-president and general manager of the United States Potash Company, but had set no date for taking up my new duties. The events of April 9th and the president's Reorganization Act that followed had opened up the way for me to resign, my goals having been reached.

Ickes was visibly shocked and burst out with, "No, you can't, you mustn't." He went on to say that we had so much to do—not just national parks, but projects like the CCC, transfer of the Forest Service to the Interior Department, and changing the Interior Department to a Department of Conservation, etc.

I tried to explain that I owed time to my family after my extensive absences during the 20 years spent with the Park Service, that financially I had to think of college for my children, and finally that most of what I had tried to accomplish had been done. Before we could discuss this any further, we had arrived at my home. A subdued secretary quietly thanked me for the day but requested that I do some more thinking about my future and then talk it over with him. He said he had to keep the directorship out of politics and wanted my replacement to be one I approved of, preferably one I chose myself. I promised him I would not be precipitous and would most certainly discuss all the ramifications of my resignation with him before it was made public.

|

| National Park Service Director Horace Albright at his desk, January

1933. Once Albright had fulfilled his 20-year dream of bringing historic

sites and monuments under the auspices of the National Park Service, he

retired from public service. Courtesy, NPS History Collection. |

Afterword

In the ensuing months Albright took three more trips with Secretary Ickes—the first a return foray into tidewater Virginia. The second trip went farther afield, by air first to Bear Mountain on the Hudson River in New York State, then to Acadia National Park in Maine. The third and final trip was to Morristown, New Jersey, to dedicate the first national historical park in the history of the nation, a project on which Albright had been working for several years.

Just six days later, on August 10, 1933, the inclusion of historic sites in the National Park Service was fully recognized as Executive Order 6166 went into effect, bringing 48 federal historic sites into the service. His fondest dreams realized, Albright chose this day for retirement. He left urging his colleagues to continue his mission, saying "We have the spirit of fighters . . . so that centuries from now people of our world, or perhaps of other worlds, may see and understand what is unique to our earth, never changing, eternal."

His actions in the years ahead prove that he kept the faith. After he became vice-president and general manager (and later president) of the United States Potash Company, he used his position and his reputation for the next 50 years to advance the causes he loved. He continued to be a major force, sometimes in evidence, sometimes behind the scenes, in shaping environmental and preservation policies throughout the land.—Frederick L. Rath, Jr.

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 24 2011 7:08 am PDT

ickes/index.htm