| Papers of the Institute for domestic Tranquility | Washington • January 1976 |

THE CONSTITUTION AS A CLUE

TO AN ECOLOGY OF HUMAN SOCIETY

or

To Insure the Domestic Tranquility

Theodore W. Sudia © Copyright 1976

The Mess We're In

The United States entered the Bicentennial of its founding in an atmosphere of anxiety and uncertainty. At home, a weird pairing of recession and inflation prevailed, with unemployment at record highs and welfare roles swelling. Abroad, the nation faced a queasy future of detente with an enemy it feared and distrusted, and at the United Nations, Third World nations artfully played the Soviet and Western blocs against each other in pursuit of their own emerging material and psychological needs.

The world economy played itself out against a background of energy blackmail—with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries literally bleeding the underdeveloped nations of their working capital and leaning unbearably on the Western economy. And accompanying it all, a Greek chorus of environmental doom was being chanted. Meanwhile, environmentalists and developers went at it tooth and claw to see whether technology or the earth would be destroyed first.

On all sides not only our national being, but our individual being appears to be coming apart. We suffer from more ills than we have cures for, accompanied by a lassitude unparalleled in recent times. The ordinary citizen mistrusts not only his government but many other institutions that until recently were taken for granted as agencies for social improvement. The war on poverty is just another embarrassing loss in the recent roster of wars. And the mere thought of giving consideration to this once urgent national priority is no longer a serious subject for discussion.

However, it cannot be said that the nation has lost its sense of purpose. Nor has it lost the quality of leadership that made our past decisions great. Instead of something lost, what seems to have happened in the nation and the world as a whole is that something has been added. That something is a growing awareness of the rights of individuals (or nations) all over the world to a higher quality life: the right to a wholesome environment, enough to eat, and the wherewithal to raise a family and participate in the banquet of life. This newly-recognized right has collided with our time-honored rules of privileged decision-making for development and exploitation. The world has quite simply, gotten smaller. The banana plantations, the rubber plantations, the tin and iron mines, the electronics factories of Japan, the oil wells of Saudi Arabia, the teak of Thailand, and other foreign environments, provide a myriad of raw and finished products from around the world. These "goods" are not only in our minds; they are also in our display windows, on our backs, and in our homes.

We are living in a global village consisting of the very rich and the very poor. Whether we like it or not our poor neighbors are close to us. The garbage dumps of industrial society are ending up in everybody's front yard. No spot on earth is too remote to pollute, and no suffering is too painful to be brought into our living rooms in living color. Our leaders have been accustomed to dealing with problems in their own way, on their own terms, with their own timetables. The problems they handled were the ones they cared to define. No one worried about contingencies, or secondary or tertiary, or "side," effects.

Today, the options for action are fewer and the decision-making processes are locked into processes of enormous detail. Moreover, they are shared by technical experts on all levels. Foreign policy for the United States is no longer handled by the elected citizen. The situation today is too complicated for anyone but technical experts. Yet the vague sense of having lost touch and control may be only illusory. There are definite signs of improvement on the human horizon, and there are definite indications of how to continue to improve. We should begin by re-examining the principles upon which was founded a nation that has lasted over 200 years. Perhaps we should reassess the self-evident truths that our forefathers thought sufficient to undergird what became the greatest nation on earth and ask whether they are sufficient for us today. Do we face the Bicentennial and say simply, "Forget it," or do we go back to the first principles and rededicate ourselves to continue what has progressed so successfully, so far?

All the pieces of the puzzle are here. No new elements are needed. Insight into the fundamental processes that made the nation work is needed now. We must rethink our national policies and advocate those that reflect our understanding of the value of man and his humane qualities. We must understand what generates apathy and fear in man, and we must bring ourselves to understand what differences can lead to anomie, cynicism and violence. These are manifestations of man's uncertain grip on his own actions, and we must seek to avoid or avert such courses of action. Thus, we should seek positive reaffirmation of the "self evident" truths upon which our nation was founded. There can be no better time than now to rededicate ourselves to rebuilding our faith in ourselves and in our nation, founded upon the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The Malthusian Hypothesis

Discussions of economic well-being, world security, and the balance of power sooner or later get around to the question of the distribution of wealth. The "have" nations are consuming the vast proportion of the earth's resources. The "have not" nations, while they seem to be supplying the raw products, do not seem to be sharing in the subsequent wealth production that results from "finishing" the raw product.

OPEC, in a narrow selfish and destructive way, is attempting to redress this balance by inflating the price of oil for its own members. Many other raw product nations are discussing the possibility of forming similar cartels. It is obvious that if other cartels could be as successful as the oil cartel, they would have been formed by now. Oil may or may not be unique in being in short supply and without an adequate substitute, since it is more the energy content of oil that we need, not oil as a raw product. The effect of alternative energy strategies has yet to be determined.

The present dilemma is a far cry from the position of the American economy 15 years ago when it was strongly suggested that in order to maintain our thriving economy, the nation would have to accustom itself to ever-increasing consumption. Our role as citizens in a booming economy was to consume, to keep the wheels of production going. The fact that the rest of the world was in pretty tough shape economically did not concern us because our own GNP was increasing at a comfortable rate and it looked as though the boom would never end.

Vietnam took the steam out of our boom and proved to ourselves and the world that we could deplete our coin and run up a staggering debt. We not only dove into national debt, we upset the world money markets with burgeoning trade deficits that called into question the soundness of the planet's economy.

Japan and West Germany, with virtually no defense budgets, did well, taking advantage of the rising world market for high technology goods; and the United States fell behind, reinforcing our feelings of inadequacy over the Vietnam war.

In this environment of uncertainty and moral lassitude and despair, it was not surprising that inflation-torn Italy should resurrect Malthus and dress him in a new suit of computer technology. The terminology was the sophisticated language of information science, but it was the same old bugaboo question: "IS THERE ENOUGH TO GO AROUND?" The answer, to no one's particular surprise, came out, "No."

It should also surprise no one that the study was commissioned by the world's very rich. The very rich would have a deep, vested interest in the question of wealth distribution, and it would be comforting to demonstrate the old Malthusian truths in the sophisticated accents of high technology.

The question posed to the computers was simple, but loaded: In the face of an exploding world population, can the food and wealth production of the world continue to provide a reasonable standard of living for all the earth's inhabitants? The answer, predictably, came out "no." The answer always comes out "no." It came out "no" for Malthus and it came out "no" for the Club of Rome. Malthus had been (and still is) assumed right and accepted with the same certainty as was Newton in celestial mechanics. Yet the gospel according to Malthus has consistently failed to fulfill its own dire predictions.

The Malthusian argument, put simply, is: Population increases exponentially and food increases arithmetically. If population has the inherent property of increasing at a faster rate than food, then the logic is correct and population must outrun the food supply and eventually world food supplies will not be enough to go around. Since man is an animal and no animal population can outrun its food supply, there must be a limit to population and that limitation must be food. Now the last sentence is correct, but it is not necessarily related to the Malthusian assumption that population increases at one rate and food at another, nor is food necessarily the first factor that will limit man's population growth. There is an irresolute logic to the relationship between food and population, and paradoxically it is the irresoluteness of that logic that provides proof of Malthusian error.

There is no question that the human population has and is increasing geometrically. What Malthus and all his subsequent practitioners failed to appreciate was that food production increases the same way. Malthus' doomsday prediction for the human race was based upon the correct notion that human populations increase geometrically. But his food assumption was based upon the fallacy that if one acre of land produced ten bushels of corn (Zea mays), then it would take two acres of land to produce 20 bushels of corn. Since the arable land surface was limited and since it was the addition of arable land to agricultural production that led to an increase in food, there was no way that more land could be found to increase the supply of food. It simply did not occur to Malthus that a little lime and a little manure could increase the yield from a single acre, and, of course, it would not have been known to him that manipulating genetics of food plants also increased the potential for food production.

Genetics and the husbandry aside, Malthus apparently did not see the relationship between the amount of seed planted and the amount of grain harvested. Eight pounds of corn per acre can produce as little as 8 or 10 bushels of corn, or with lime it can produce 25 bushels, and with varying degrees of the best agricultural practice it can produce 100 or 200, or even 350 bushels (on a single acre); the theoretical maximum is about 400 bushels.

Average corn production in the late 1700's was about 8 to 10 bushels; by the mid-1800's it had moved to 25 bushels; with the addition of lime to the soil in the mid-1900's, corn production in the United States was about 40 bushels; and it is certainly higher than that now, with good land in the corn belt repeatedly producing 100 bushels—with 200 bushels to the acre not rare.

Corn production has been and is geometric. Even if we look at the abysmal 18th Century yields of 8 to 10 bushels, that yield was also geometric, for 8 pounds of corn seed produced 8 bushels of corn yield. (At 54 pounds to the bushel, that 8 pounds of seed yielded 432 pounds of grain.)

Why shouldn't food production be geometric? Food plants and animals are biological organisms just like humans. If humans have a geometric growth potential, then so do cows and sheep and wheat and corn and potatoes, etc. The only condition necessary for population increase is to have the parent organisms live long enough to produce more progeny than themselves and have the progeny do the same. Malthus' error was that he associated food production with areal extent of land but population growth with the biological properties of humans. In essence, he fell afoul of the apples and oranges problem and equated two non-equatable entities.

The simplicity of Malthus, however, has been greatly appealing, particularly when it also tells those who pay for the message what they want to hear. That unmistakable message is that since there is not enough to go around, the rich are simply condemned to remain rich and the poor are condemned to remain poor. There can never be equity in a situation of insufficiency and it just happens to be "morally and ethically" convenient that the progenitors of the earth's children commit the act that causes the inequity in the first place. They have children. If they have children in a world in which there is not enough to go around, then they must suffer the consequence of their individual actions, and that consequence is unavoidable poverty.

Since there were so few wealthy, they did not contribute very much to the population problem and consequently could not be held to account for it. On the other hand, there was no real reason to share their wealth either since in any event there wasn't enough to go around.

The simplest most eloquent proof of the fallacy of Malthus is that many decades after his dire doomsday prediction, it still has not come true. It seems as though it should have come true and there is speculation from time to time that if we wait long enough, it will come true. There have been increases in world population that would have in all probability given Malthus apoplexy. And yet the people are here, and food production has kept pace with population. How do we know that? We know it because we have the population. It is not possible to have people without food. We have the people, therefore we must have the food. It can be said, of course, that the poor are in wretched condition, that there is much malnutrition and infant mortality is high, that communicable diseases are rampant, that life expectancy in many parts of the world is quite low (but always high enough to get into a breeding cycle), and that poverty is crushing. But while the poor of the world are wretched, they are not worse off than the poor of previous generations. And that statement can be made for each generation. No generation is worse off than the one that preceded it...not after wars, nor famine nor pestilence, not after barbarian conquests, religious wars or world wars. (The jury is still out on nuclear war—hopefully it will never come in.) Each generation of man from the dawn of time has progressed over its predecessors.

Now, if the problem of feeding the people of the world were subjected to industrial analysis, it would have to be rated as a highly efficient process. Businessmen in most enterprises are eminently satisfied when production quotas can be regulated to within plus or minus 1%. If the world's food supply were "off" by a factor of 1%, it should result in the starvation of 35 million people a year (1% of 3.5 billion). A ten percent error, which in many industrial processes is quite acceptable, would result in the death by starvation of 350 million people a year. None of this has happened. In no year has a starvation rate of 35 million been reported for any combination of circumstances, let alone 350 million.

It might be argued that people don't die of starvation because they die of other causes that become critical because of malnutrition. That may be true, but the presence of disease organisms in the world is related to public health and sanitation, not to food supply. Malthusian economics deals with the relationship between population and food supply, and attempts to prove a population/food problem by citing population/disease statistics are simply not honest. People will continue to die for a great number of reasons. Right now the chief causes of death in the affluent nations seem to be heart attacks and cancer. The former is in part related to excessive food intake, the latter, to carcinogen-laden environments generated out of the advanced nation's wealth-producing technologies. (The greatest death rate the world ever experienced was the Black Plague of the 14th Century where perhaps one-third of the population from India to Western Europe died in a relatively short period of time. Only nuclear war seems to pose such a catastrophic death rate for man. We have demonstrated that we can do something about epidemics with modern medicine. We have yet to even begin the search for the antidote to nuclear war. We think it is disarmament, a negative course of action inasmuch as it is an agreement not to do something that should not be done in the first place. What is needed is a positive approach, i.e ., the agreement to do something that will replace war in the human behavior repertoire.)

Malthus was wrong for another reason—one for which he cannot be blamed since he could not have known about it. The new factor in the food/population equation, which did not emerge fully until about two decades ago, is the rate of increase in technological information. Great stirrings in this direction already were occurring in Malthus' lifetime. The foundation of modern science, laid in the previous century, had resulted in geographical discovery. On these bases, in the 18th Century, man began his great constructs of industrial and scientific discovery. The reason food kept pace with population was that technology also kept pace with population, and all three entities share the same growth properties. Food, population, and technology all demonstrate logarithmic growth rates. Information, increasing geometrically along with population and food, was no doubt the critical factor in alleviating severe food shortages. Often the problems of famine center around the information, or lack of it, of food supplies and how to mobilize them. A common complaint of 16th Century grain speculators rushing supplies to a famine—stricken area was that frequently too many merchants were involved, bringing too much grain and consequently depressing the price.

Can it be concluded from the foregoing arguments that there is no limit to population growth? The answer obviously is no. Population is still tied to food in the most simple and elementary biological fashion. Without food, animal populations perish. Large populations of animals without food "crash." Food is a critical limiting factor in population size. The relationship is intrinsic and non-negatable. The fact is that so far the increase in information has mediated food production and has enabled it to keep pace with population. And we must admit that population is still increasing, therefore, the Malthusian principle already has failed. A mere arithmetical gain in food would have "crashed" the human population long ago. In view of the proven ability of technology to boost food production geometrically, we must now restate the food/population question, figuring technical information into the equation. The question that emerges asks is there a limit to the population the earth can sustain, deducible from our present information about food, food production and population growth? The answer to this rephrased question cannot be made with certainty, possibly because we still lack (as Malthus certainly did) same critical insights into the problem. Intuitively we know there must be a limit, but what are the factors that will determine it? We know that food certainly will be a limiting factor, but what are the factors limiting food production?

Other materials such as minerals and nutrients may in time prove limiting. It seems most unlikely, however, that space itself will be the ultimate factor halting population growth. The problem becomes amazingly complex; it most certainly transcends the Malthusian assumption.

The time has come to lay Malthus to rest and stop begging the question of the distribution of wealth. The state of information today demands instead a re-examination of some of the properties of wealth production. A considered analysis of the problem of food and population may reveal taking full advantage of today's command of data and the systems for analyzing it, yet other relationships more significant than food and people.

Ten thousand persons a day starve to death. On a yearly basis this amounts to 3.56 million people, a figure which incidentally is only a one-tenth of the 1% that would be deemed to be excellent in any industrial process—not condoning however that anyone should starve to death. But the matter of the starvation rate alone does not reveal the whole story, for some 200,000 persons are born each day. This amounts to 73 million more mouths to feed every year. The planet as a whole must support a net increase of about 68.5 million people each year. The fact that it is still possible is borne out by the simple fact that it is happening. Yet the handwringing and wailing continues. "How long can we keep it up?" The question is truly rhetorical since no one seriously has undertaken to find the answer. Instead, chicken farm economics is dredged up and we are bludgeoned with ridiculous projections of a world with two people per square meter.

This kind of thinking is not helpful; the kind that would be productive would have to begin with the devastating truth that those who starve to death do so because they cannot afford to buy food!

Recent dislocation in world food resources are occurring because the Soviet Union and the OPEC nations are purchasing larger and larger amounts of food in the world food markets, increasing the price of food and making it less available to those who are unable to compete economically for it. This is quite a different problem from the problem Malthus proposed.

The study commissioned by the Club of Rome was entitled "Limits of Growth," and the conclusion implied just that—that there would be shortages of natural materials which in turn would limit industrial growth. The same old Malthusian error permeates the Club of Rome analysis, but this time with less excuse. While indeed there is a finite amount of iron, chromium, zinc, molybdenum, or even carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, and while the growth of population is still increasing geometrically against non-geometric discovery of resources, the factor omitted from the analysis is, again, information. Information growth is logarithmic. Through all the 3 to 5 million years of the history of man's technology, information has increased in a non-linear fashion and indeed has not just "made possible" but caused the acceleration of population growth we are witnessing today.

Whether the information dealt with basic survival, hunting, agriculture, industry, health, or whatever, it has increased the possibility of man's survival. (Since, in the strict biological sense, the number of individuals in a population is related to the numbers who survive to become the breeding group, population growth must inexorably result from simple increase in survival potential.)

It has taken some very sophisticated insights into population dynamics to understand that the very same information that can result in population growth can also result in its control to zero population growth or the steady state, since what is required is an understanding of fertility and fecundity and the sociobiological processes that regulate them. This sophistication, however, has come only recently, while the popular notion of population—trickily decked out in computer technology—is still riding the neo-Malthusian doomsday devil.

In all cases so far where either food or industrial raw materials have been cited as factors that will bring on the population crash, it can be shown that the law of the marketplace—the economics of supply and demand, not Leibzig's law of the minimum—was operating.

Since all the Club of Rome data apparently is captured in computer compatible form, presumably some new analyses and predictions could be made, based on the fact that what we are producing through our industry and our economy is wealth. Since wealth is related as much to information as it is to resources, a new set of predictions more reasonably related to future outcomes should be forthcoming. When we add to the Club of Rome data what can be said of the rate of discovery of new information and how that discovery and its distribution can affect the world outlook, we should look for the computers to produce anything but doomsday predictions.

To understand the form of some of these predictions, it is necessary to discuss the properties of resources, information, and wealth.

Properties of Information

The resources of the earth are finite, but they are enormous; they are also reusable. The latter statement is the First Law of Thermodynamics: Matter and Energy Can Neither Be Created Nor Destroyed. The Second Law adds the kicker: They Will, However, Become Dispersed Or Diffused.

Resources that are rendered reusable by biogeochemical processes utilizing the energy of molecules and atoms, diffusion, convection solution, etc., are termed renewable. Those that must be reclaimed by energy inputs other than the biogeochemical processes are termed non-renewable. Non-renewable resources are macromolecular, e.g., beer cans, glass bottles, paper, automobiles, etc., and they require energy systems at the macromolecular level to recycle the—hands and backs, trucks, railroads and trains, etc. In the "real world" where man operates, the difference between the two is the amount of energy under the control of man (as opposed to "naturally" occurring energetic processes) that is required to reuse materials once used.

The great loss of materials from modern industrial processes is not due to any law that says they cannot be recovered. But only within the last few years has it penetrated our economically thick skulls that the recycling properties of natural ecosystems hold a profit for industrial processes and that in part, industrial processes are natural ecosystems, differing only in that they are dominated by the species Homo sapiens and pushed along their cyclic way at a greatly accelerated tempo. Industrial ecosystems differ most dramatically from nature in their management. Since industrial processes are governed by segmented economics, no one is currently chargeable with the responsibility for closing the loops of industrial processes to make them truly recycling.

Too many diverse economic entities share the economically profitable, artificially speeded-up part of the cycle, and too much of the "waste" loop is dumped too fast on the natural systems, with their slower, more deliberate tempo, with only the EPA and a few conservation groups blowing the whistle on the flagrant waste of resources and its unnecessary concomitant threats to life. The need for the role of the central government (and international agreements) to assign responsibility for assuring that the basic ecosystem principles are applied to the industries that constitute our industrial economy should be self-evident. How else can we have the least assurance of the moral behavior necessary to support, sustain and enrich life, in an environment that encourages profit-taking at the expense of life and the living environment?

No amount of management will cause finite resources to become infinite. But the finite aspects of the resources of the earth can be made to assume same of the properties of the infinite through ecosystems management. Needless to say, more attention must be paid to the information required for this type of management.

At this point, however, it becomes important to shift our attention from the remaining resources inventories of Earth, which for all present and foreseeable future purposes are enormous, and look instead to the real preoccupation of—production of wealth. As Buckminster Fuller has pointed out, wealth is related to information (Fuller used the word "knowledge," which to the author seems much too restrictive), and the fact is that wealth production is far more dependent on our information banks than it is on our resource reserves. A sunbaked, clay washboard studded with rough stones has a certain finite value to the Amazon Indian who uses it to wash her family's clothes. The fact that the stones embedded in its surface are diamonds is of absolutely no concern until it is known that they are diamonds and what diamonds are worth in the world outside her society. Their worth to the Indian woman lies only in their roughness and the relationship to cleanliness of clothing which her mind has stored as information. Most things have value after something is known about them in relation to the needs, present or future, real or frivolous of the society which perceives them. (Who "needs" a pet rock?" Yet that perceptual quirk grossed $10 million for its creator.)

The relationship between resources, information and wealth can be

described with the following notation:

Wc =

Wc =  Rc x

Rc x  Ic

Ic

where

W = the sum of all the wealth

R = the sum of the resources of the universe

Ic = the sum of cosmic information

Stated in words, the equation says that the sum of all the wealth of

the universe ( Wc) is the

product of the resources of the universe (Rc) when multiplied

by the information (or wisdom) of the universe (Ic).

Wc) is the

product of the resources of the universe (Rc) when multiplied

by the information (or wisdom) of the universe (Ic).

In the equation, R is assumed to be finite in spite of its reusability and enormous quantity. Ic is represented as the total of cosmic wisdom. It is the information that is inherent in and responsible for the universe as we know it. It represents the basic physics and chemistry that produced what we know to be the earth, sun, moon, stars, etc. It is on the basis of this cosmic information that sodium reacts with chlorine to form sodium chloride. All of science, the humanities and theology are attempting to discover the properties of Ic. The magnitude of Ic cannot be stated. It is assumed to be infinite inasmuch as the rate of its discovery is logarithmic and, like light, shares the property of being everywhere dense. In all likelihood information (Ic) is a fundamental property of the universe, sharing an equal status with energy, matter, tine and space. It must be recognized that the universe, utilizing cosmic information, evolved very nicely without man, who is only just now in the act of discovering what Ic is. If we rewrite the equation as a limit, we have the following:

| Limit |  W W0-->infinity | = |  R R0-->N | x |  I I0-->infinity |

Since cosmic wisdom (Ic) approaches infinity, cosmic wealth (Wc) would also approach infinity, since any finite number multiplied by a transfinite number is transfinite. If cosmic wisdom (Ic) were to approach zero, then cosmic wealth (Wc) would approach zero, regardless of the amount of resources of the universe (Rc). Now, if the resources of the universe (Rc) are greater than zero but still finite, it follows that wealth can still approach infinity. What the equation really implies is that if cosmic wealth is really the product of cosmic resources and cosmic information, then the universe, including the earth, was infinitely wealthy, with or without man.

Man is most interested in wealth that relates to man. In this special case, a new information element must be introduced. First, it must take into account the evolutionary development of all living organisms, including man. This we represent by the following notation:

Wev =

Rev x

Iev

Wev = sum of wealth

Rev = sum of resources

Iev = sum of information derived from biologic phenomena.

It should be obvious the Iev is a subset of Iev, and since it has the same rate of discovery when probed, is also logarithmic, i.e., approaches infinity.

It should become apparent at this point that information shares with light the property of being everywhere dense. No matter what the methodology, the search for understanding leads to ever-increasing information. Whether research is conducted toward reductionism or generalism, there is no end to the information it yields. Each evaluation of research or inquiry seems to lead to a finer approximation of the true situation which in turn leads to yet a more refined hypothesis and a more complete answer, and so on and on without ever a final conclusion being reached. Karl Popper in his Conjectures and Refutations describes this process in great detail. As a word description of a theory of approximation of a transfinite series, it implies that the process of discovery is the evaluation or approximation of an infinite amount of information about any given subject. In a very rough way this insight points to what is another characteristic of infiniteness. Simply put, subsets of transfinite entities are always transfinite themselves, leading knowledge-seekers always to infinity, no matter which branch they elect to pursue. The easiest example out of mathematics says that the subset of odd numbers (1,3,5,7.. .N) is equal in magnitude to the counting integers (1,2,3,4... N) because for every odd number we can put a counting integer into correspondence with it and not run out of either odd numbers or counting integers.

1,3,5,7.....N

1,2,3,4.....N

The paradoxical conclusion is that the number of odd numbers is of the same magnitude as all the numbers put together, because we can count the odd numbers, yet never run out of either odd numbers or the numbers to count them with; but not only that, they match up with no odd numbers nor any counting numbers left out.

In a similar fashion the amount of information associated with evolution, while it is a subset of cosmic evolution, again seems to be infinite because like cosmic information there seems to be no end to its discoverability. If man were to have not developed language or technology but simply evolved as a beast of the field, he would have participated in the wealth of the world simply through:

Wev =

Rev x

Iev

Self-awareness, a conscious grasp of his destiny, might forever have remained beyond his comprehension, but he would have benefited simply because he was part of the system. But man has done more. He has discovered his own consciousness: he discovered the historical past and the future, and he invented tools of design—of which language is the single—most important one and through it has developed the elaborate technology we know. In comparison with all other information, it is the information of design which most crucially affects the survival of man's technology and his "way of life," allowing him to control his environment and, through the concept of property, to accumulate wealth unto himself. Man can nicely survive as an animal without language or technology, probably much the same as other higher primates. By extension of the biological evolution equation, this relationship can be described in the following way:

Wdes Wdes0-->infinity | = |  Rdes Rdes0-->N | x |  Ides Ides0-->infinity |

Information of design shares with cosmic and evolutionary information the same property, transfiniteness. As a subset of cosmic information, it shares in its properties and characteristics.

Information of design differs from cosmic wisdom (Ic) and evolutionary information (Iev) in one special way. Since it is the information man uses to regulate his technology activities, it is information directly available to him for the production of his personal wealth. Out of the mass of cosmic information, which is "everywhere dense," man has conceived and carved himself a tool to use to enhance his survival and for his own aggrandizement. Obviously all of these forms of information are relative, and the process of scientific discovery consists of adapting more and more of the information in cosmic wisdom (Ic) and evolutionary information (Iev) to the information of design (Id).

The inevitable conclusion of this analysis is that the world was and is infinitely wealthy. The amount of wealth available to man has steadily increased and seems to have the similar property of ever increasing. As a matter of fact, it is not difficult to demonstrate that at any given time in man's existence, surplus wealth has been produced, providing ample evidence of the increasing wealth of man's world. Its production seems to have posed no particular problems; on the other hand, its disposition has proved infinitely difficult.

No "knowledge" is considered "useful," nor will it long remain in the tool chest of any individual human unless it contributes to his survival. Humanity's perception of what is real in itself and its surroundings eventually must prove useful as a means of coping with surroundings and perpetuating self, or it is discarded. Consistent failure to take this step would result, very simply, in an end to humanity, whether it is a failure to come to terms with the environment or failure to come to terms with other men. It is by such no-nonsense events that the universe even-handedly reveals itself. Man's continued existence then would seem to depend ultimately on a correct perception of the universal systems within which he is embedded—a system which does not require him to survive.

Wealth is one such basic percept which currently clamors for review. Into it are plugged the problems we call population, pollution, poverty, crime, and war. The world's political situation is constantly being described in terms of wealth and/or its subsets as named above, but until recently very little attention has been given to wealth as a generic root problem, nor to a more specific consideration—namely, the disposition of surplus wealth.

It is the contention of the author that had the Club of Rome addressed itself and its huge resources to an honest evaluation of the world's surplus wealth—its present and possible future disposition—humanity would today be well beyond the current replay of Malthusian doom-saying. Resource depletion and poverty is NOT the world's prime problem, nor has it ever been. General systems theory and computer technology are today at a state of readiness to cope with the real problem of human society today—which is to understand the reality of ever-increasing wealth and to solve the incredibly complex problems that such wealth poses.

While civilization's problem is seldom described in terms of surplus wealth disposition, nevertheless, the patterns of ownership of wealth and distribution of wealth clearly demonstrate that the problem of surplus wealth has not been solved. While it may not have been apparent at the time, it is relatively certain that surplus wealth has been disposed of in public works property from the earliest human times. The early walls and ziggurat of Babylon must have consumed enormous surplus wealth. The pyramids of Egypt, the cathedrals of Europe, the Great Wall of China, all the great relics of the past, attest to mankind's creative copings with the problem of surplus wealth. We have differentiated and stratified the wealth of nations of the world in infinitely more sophisticated ways since the days of Teotihuachan, Tikal and Copan, but we are still faced with the sane problems that led to their construction long ago.

The GNP of the world continues to increase, despite war, famine and pestilence. In the not too distant past, the myth of the efficacy of war as a creator of industrial, prosperity and technological advancement was highly touted. The unseen relationships included the fact that in wartimes, manpower and money not ordinarily available for problem-solving (i.e., "information") became available. The result was a new spurt of wealth and a temporarily improved human condition.

The wealth, resources and information equation does not support the contention that all the problems of man can be solved forthwith and that the return to Eden is imminent. As a matter of fact, to return to Eden, we have to shed the information of design and the language and technology that go with it and return to the information of biological evolution, naked and innocent. What the equation does state is that wealth production is a logarithmic function and that projected into the future, this function will continue to produce surplus wealth. What becomes of that surplus wealth depends on what man conceives as a desirable world.

The Properties of Man

Man has been described as the toolmaker, the specific epithet Homo sapiens signifying man the wise. Man has also been described as the naked ape. Certainly man is in the mainstream of biological evolution and it is with no difficulty that man can be placed in the kingdom Animialia; phylum, Chordata; subphylum, Vertebrates; class, Mammalia; order, Primata; family, Hominidae; genus, Homo; species, Homo sapiens. Man shares the genus Homo with several other species of man, all others of which are now extinct; the family Hominidae with other known genera of man, also extinct; and the order Primata with all the great and lesser apes.

Man is distinct; he has highly developed technology; he has language, and he sees himself in dominion over the world. But man did not always have language and he did not always have high technology. It surely can be postulated that at a distant time man must have had little if any technology and was indistinguishable behaviorally from other animals of his given size and shape. As a matter of fact, man's biological behavior as distinguished from his technological behavior has probably remained unchanged for as long as he has had his present anatomy, morphology and physiology.

Since man has had language and technology for at least the last three million years, and since man has considered himself in command of the earth for the last eight to ten thousand years (probably since the invention of written language), it is difficult to see from the 20th Century what man must have been like without language and technology. Yet it is the behavior of man who evolved before he invented language and technology that we must understand if we are to make sense of the creature that is modern man. It is language and technology imbedded in the matrix of man's biological evolution that make him the unique and peculiar beast that he is. It is the ethological nature of man in the animal social context of his community life that must first be recognized and evaluated before the impact and influence of language and technology can be assayed.

And in the context of man's ethological social milieu will be found some of the behavior that is paradoxical in a creature made so powerful by technology. The question is terrifyingly simple. Is man biologically equipped to handle the vast technological power he has discovered and is now attempting to control? The paradox is why is so powerful an animal as man at the same time so fearful and anxious? Why is so powerful an animal as man at once so cruel and devious, so cunning and sly? Why is so understanding a man so at odds with himself, other men and nature? Why must all be conquered? This is not to discount the presence of man's humane characteristics. The curious fact remains that modern man is the most powerful animal in the world and yet singly and in groups he is largely paranoid, fearful, anxious and destructive. This paranoia of man is not related merely to the problems of war; it permeates his daily group life in ethnic and racial prejudice, and in his individual man-to-man inhumanity, manifesting itself at its lowest levels in child abuse, wife-beating, distrust of neighbors, and the growing phenomenon of crime-against-persons—the tiger that prowls our streets.

The behavior higher animals display characterizes these animals as predators or prey. And within social groupings of individual species, dominance hierarchies are commonly observed. The dominant animal in such social groupings is frequently referred to as the alpha animal.

While the term alpha is used by animal behaviorists to indicate the dominant animal in a social group, such as the alpha wolf in a pack, the use here is extended to the concept of an alpha species. In this context, any animal species, the full-grown adults of which seem to have no ordinary fear of other animals, are considered an alpha species. Examples are lions, tigers, grizzly bears, badgers, blue sharks, blue whales and elephants. It should be noted that not all these animals are predators. Some are terrestrial, some marine; alphas need not even be carnivores or even omnivorous. All they possess in common is a seeming lack of fear of other animals—any other animals. There may be accommodations—such as lions avoiding elephants, grizzlies avoiding man—but when confronted, these animals will not retreat.

In contrast to alpha species, there are beta species. These animals are prey in the food chain. Goats, deer, pigs, sheep and rabbits are examples of this group. Generally speaking, these animals flee when approached and are frequently the prey of most of the predatory animals named on the alpha list.

The question now is, on which list does man belong? On the face of it, this may seem like a silly question, since man can, at will, subdue or tame virtually all the animals on either list, with the notable exception of himself. But this dominance of man was attained only long after he had achieved language and technology. Man with a gun and with extensive knowledge of lethal weapons is a formidable killer, but what of man in his pre-language days, without tools of any kind? In such a circumstance, man was not a very formidable animal and was in fact at the mercy of groups of animals much smaller than he in size. Even the lowly reptile can be a formidable foe of unarmed, unaware man. It is the man without the gun or without technology reacting to the environment, with only his biological tools, that we must understand in order to understand the mentality that is wielding the enormous power of modern technology. We again have another paradox where man, biologically, has all the attributes of a beta species, but with technological power, that makes him an alpha.

Human life expectancy in pre-language man must have been quite abbreviated, perhaps as short as 15 to 20 years, with 30 constituting a venerable ancient. Births and deaths, in all probability, were in close balance, and man by most estimates of populations must have been a rare species indeed—found in only a few localities of Africa and in low numbers.

It is only after the invention of language and the proliferation of tools that man improved his survival potentiality to begin his migrations that ultimately have taken him to all the terrestrial habitats of the world. But man spent millions of years developing his survival ethology without tools and without language. His behavior repertory was fully developed by the time he discovered and developed technology, and it has been only in very recent years that his technology has given him unquestioned dominance. This cannot have happened more than 70 to 100 thousand years ago—a very short time, evolutionarily speaking, an impossibly short time frame within which to modify biochemical-physiological neural patterns.

So it is this man, without tools, without language, embedded within the food chain, the prey of many predators, who crouches inside a new and enormous repertory of tools which he can use at will for good or for evil. It is this creature whose behavior we must understand before we can sort out and make sense of modern man and his society. Modern man lives in a beta body, possesses a beta brain, but wields alpha power. We might begin our sorting out process by trying this fact as an explanation for the popularity of so-called "blood sports." It may serve to explain, at least partially, the pictures of anglers with hundreds of fish (caught for sport, not for the market), and the hunters with dozens of slain ducks, or the trap shooters who once practiced on living passenger pigeons. Perhaps it helps explain why the plains buffalo was nearly exterminated; why even in war most infantrymen do not fire their weapons and why firing for effect is more efficient than firing at targets. And perhaps even more to the present point, it may explain why man is afraid of man.

The human race first discovered the control of life and death, and in the millenia-long struggle for individual and group eminence within the species there has ensued a veritable outpouring of creative development, coupled with a destructive streak unparalleled in the history of evolution.

How can these conflicts and paradoxical properties of man be rationalized? How can man come to grips with the fact that he is prone to beta judgments carried out with alpha power (revenge on hapless animals and men, torture, mass destruction and genocide)?

At a number of significant points in human history man has come to the self-realization of his duality and has instituted social orders to reduce the inner conflict of this paradox. It is likely that the earliest men who had language, millions of years ago, were aware of man's destructiveness and also of his gentleness and compassion. The Flower People of Shanidar are probably the most recent of preliterate man to display a patterned understanding of their own essential humanness.

In Sumer and Greece, in Renaissance Europe, and again in the 18th Century—the Age of Reason—the essential humanness of man was discovered and rediscovered. It was in this latter environment of enlightened self-interest, the Age of Reason, that the Constitution of the United States was fashioned. All those involved, but especially Thomas Jefferson, were completely steeped in the concepts of individual freedom and in the rights of individual men. What had, in fact, happened was that man's right to prey on his fellowman was questioned, and a great effort was made to endow the beta animal with the technological (language) means to become an alpha animal.

The concept (rationale) was simple: Unless all men had the right to be free, freedom could not be guaranteed for any man (the alpha process). No man is free if any man is enslaved (the alpha man). (The seeds that made the Civil War inevitable lay in this constitutional concept.)

The intellectual thrust of the Age of Reason, simply put, was to urge man with his tremendous power for good and evil to adopt an alpha behavior repertoire, and with his "reason" to transform his beta being into the higher order of being which is characterized by the alphas. A man with enormous power who feels no need to use it epitomizes this mentality. (This concept of bound power is common in Eastern philosophical thought but in Eastern philosophy the thought was directed to individuals, not communities. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States direct this thought to the community of man.)

The glowing statement in American history that most clearly demonstrates this thinking is the phrase in the Declaration of Independence that states "all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." What the Declaration states, clearly, are the basic rights of man from both an apolitical and an ecological viewpoint. The thread of history representing this insight began with the Virginia Resolutions, which were the forerunner of the Declaration, and, eventually, of the Bill of Rights. However, when the Constitution was written, following the failure of the Articles of Confederation, the Bill of Rights was excluded—a condition that was rectified later during the ratification of the Constitution.

All in all, the Constitution of the United States is a remarkable document, which succinctly enumerates the rights of man, both from an individualistic point of view and from a community point of view.

It is the Preamble of the Constitution that is of prime interest in this discussion, for in a very few words it lays out the basis for establishing governments among men. An ecological analysis of the Preamble then should give us some insights into the basic ecology of government.

The Preamble states: "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

Itemized, the Preamble aspires to (1) establish Justice, (2) insure domestic Tranquility, (3) provide for the common defence, and (4) promote the general Welfare. (The choice of capital letters belongs to the Founding Fathers.) (To the author's knowledge, the Preamble has never been used to argue a case in law, though he can see no reason why it should not have the same if not more authority than the Articles.)

Items 1 and 4 of the Preamble are addressed to individuals. There can be no justice unless justice is available to every individual without exception. Similarly, the general welfare of the nation depends upon the welfare of each individual and, no matter whether the concept of cradle-to-grave socialism is espoused or rugged individualism upheld, the concept of general welfare is meaningful only in the context of the welfare of individuals.

Items 2 and 3 of the Preamble have different properties. They are precepts that apply to the community of man. Providing for the common defense is a matter for the nation as a whole to address, and from the ecological point of view, it is community activity. Individuals cannot provide for the common defense; their efforts must be integrated into a community effort to provide for the defense of the community as a whole—hence, "common" defense."

Justice and general welfare are reasonably well understood concepts from the political and economic point of view. Justice has been formalized in government for a very long time (at least from the time of ancient Sumer) and is perhaps the better understood. The general welfare has only recently been formally accepted into the structure of government, and while the broad concept of general welfare is accepted, the details of carrying it out do not have universal concurrence.

Providing for the common defense is similarly a well understood concept, particularly since the nation was born in a contest of arms and into a world which has had wars too numerous to enumerate before its founding. The still somewhat enigmatic concept of the Preamble is Item 3—to insure domestic tranquility.

The fact that insurance of the domestic tranquility is the least understood of the great principles of the Preamble is easily seen from the fact that the other three are ensconced in full-fledged departments of the government. The Justice Department and the Judiciary have been erected to establish justice. The Departments of the Navy and War, later combined into the Department of Defense, provide for the common defense. (The National Guard is the "well-ordered militia" of the Bill of Rights.) And the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare is wrestling with the great notions involved in providing for the general welfare.

We are left to wonder what agency of the government has been established to insure the domestic tranquility. To understand the problem we must first understand domestic tranquility.

In its simplest aspect, domestic tranquility relates to the quality of life and of the human environment. It is most concisely epitomized in the Declaration of Independence where it is stated that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights among which are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is the pursuit of happiness that forms the first principle of tranquility. Tranquility is a state or a condition. Tranquility is not possible to individuals unless it is a property of the community. Communities under stress—physical, psychological, or economic—cannot be tranquil. They can be quiet, and submissive, but they are not tranquil.

Tranquility is a property of communities that devolves upon the families and individuals living in them. It is specifically the quality of life which is directly related to the quality of the human environment. Tranquility is not placidity, nor is it torpor or stupor. Tranquility is healthy and vigorous pursuit of happiness. It is manifest by physical fitness, the love of man and nature, a full realization of the virtue of life and the virtue of the human environment and their relationship to each other and to all the habitats that form the biosphere.

Tranquility means having fun as well as pursuing serious interests; it is the opportune setting within which to work hard at productive labor. At its most basic, tranquility is freedom from fear and anxiety. It is recreation and the arts—music, drama, philosophy. Tranquility encompasses all those aspects of the human existence that are achievable through the highest motivations of man's intellect, and it is the necessary adjunct to the rigors of survival. It is the ideal environment in which to raise children. In short, the creation of tranquility in human communities and in the wider environment of man is the manifestation of the essential humanness of man.

Tranquility is the principal characteristic of a free society. Without tranquility, man is enslaved by circumstance, economic or political; without tranquility, even in his modern socio-economic context, man is physically back in the predator/prey relationship. Freedom to pursue happiness, guaranteed human rights, dignity, freedom from fear and want—all of these relate to the community of man, the tranquil ecologically mature human community. It is no accident that a synonym for tranquility is peace.

Community Stability

Of the four major precepts of the Preamble to the Constitution, we have seen then that two, justice and welfare, relate to individuals; and two, defense and tranquility, relate to communities.

It is of interest at this time to consider these four precepts as ecological factors and to consider to what extent they affect the stability of the communities which value them.

From an ecological perspective, it is convenient to consider communities as processors of energy. Mature, steady-state communities are those that can process large amounts of energy and use them to maintain and stabilize themselves. The achievement of a desirable steady-state results from the interaction of various environmental factors and it is the ability of the mature community to channel its energy into productive and maintenance functions that lead to its stability. This is not to say that the mature community is static. Far from it. The mature community is dynamic, capable of changes and improvement, and able to extend its boundaries. It does all these things, however, without changing its principal characteristics or purposes.

From our previous discussion of wealth, the question is, where should increases in wealth increments be applied? (The FY 1962 Federal budget was $95 billion; the FY 1977 Federal budget was in the neighborhood of $395 billion; the FY 1979 Federal budget is in the neighborhood of ____ billion; and the FY 1980 Federal budget will be in the neighborhood of 550 billion—pretty positive proof that there are increased wealth increments, even if one takes into account inflation, the war drain, the national debt and budget deficits.)

If substantial new increments of wealth are applied to justice, this means one of two things: either more funds are available for police and police work and to the practice of law and the judiciary, or more money is made available to individuals to exercise their rights under the law. The former case carries the disturbing implication of tendency toward a police state; the latter (as recent experience has shown) results in large numbers of people suing for their individual rights in the courts. In the latter case, the system of jurisprudence is overwhelm, and more importantly, the status quo of existing communities is severely disturbed. (This happened in the OEO legal programs for the poor, where cities and states were respectively challenged by previously impotent citizens. The net result was pressure to kill the programs.) Large grants to police departments, far from preventing crime, seem primarily to intimidate the law-abiding citizenry, further inhibiting the healthy exercise of expression and dissent.

Quite obviously, the channeling of large amounts of additional money into "justice" has a destabilizing effect on communities of free men, since its use on behalf of the disadvantaged tends to tip the power in favor of individuals over the community, and its use on behalf of law enforcement tends to make the community repressive of the individual. Neither pursuit leads to the kinds of communities envisioned by the founding fathers. This is not to say that justice is not of paramount importance. What it says is that justice is not an appropriate sink for substantial increases of the national wealth without risking revolutionary change in society.

If large amounts of wealth increments are dedicated to welfare, again the effect is to upset the status quo and to destabilize the community by upsetting the relationship between private property and public wealth. If there has ever been a contentious issue in the United States, it has been that of welfare. It seems to matter not how much people need help or how many of them need it—it is grudgingly given and is accompanied by a continuous hue and cry over welfare-cheaters.

Gainful employment is, of course, the alternative preferred by both the government and the welfare recipient, but no plan has yet been developed that can provide full employment under conditions acceptable to all. And the use of public money to purchase housing that the poor could own is anathema, in spite of the fact that the same money allows the "slum lords" to become wealthy. It is more than obvious that large increments of future wealth dedicated to welfare will have a destabilizing effect upon present communities, since they will be given with large amounts of resentment.

The changes that occur in human society when large influxes of monies are poured into justice and/or welfare—the two principles that deal with individuals—are rapid and unassimilable. They are revolutionary rather than evolutionary. Revolutionary changes are almost always accompanied by fear and repression, whereas evolutionary change usually carries longer term impact and is perceived over time as "progress" by those either viewing or involved in it.

Providing for the common defense plays a unique role in the ecology of the human communities of the world. Not only does the channeling of wealth into defense strengthen the community through feelings of pride, patriotism, and solidarity, it perfectly expresses the paradox of man with his beta brain and his technologically alpha power. The economic and the ecological coincidence is the simple fact that money spent on defense does tend to stabilize communities (as opposed to money spent on a police state).

Citizens enthusiastically do support the defense needs, and there is just enough latent (and justified) paranoia (in part due to the evolutionary development of man himself) so that the defense budget can and has become the vast sink for all the excess wealth that can be generated in human societies. Defense budgets become untouchable.

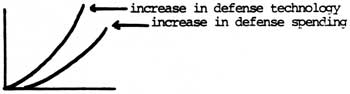

There seems to be no limit to the funds that defense can absorb. Since the means of waging war and mounting defenses for war is a highly specialized technological process, the information needed to wage offensive and defensive war grows at a geometric rate. As a result, the demands to translate this technology into hardware will require matching geometrically increasing amounts of money. (It is estimated that 10% of the GNP of the world is devoted to armaments. Since the GNP is increasing as a power function, a simple deduction tells us that funds for defense are increasing geometrically.)

Since defense as an activity has a substantial research and development phase, it would be valuable to look at the relationship between research and product or system development. The estimated increase in expenditure necessary to translate research and development into products is roughly 1,000 to 1. $10 million spent on weapons development will force an expenditure of perhaps $10 billion in a delivered weapons system. This is not an argument to reduce defense research. It is merely a demonstration of the relationship between increases in technology which are logarithmic and the concomitant logarithmic increases in expenditures.

In addition, the current spectacle of underdeveloped nations spending huge sums on armaments. indicates the machismo over-compensation of beta man trying to achieve, through instruments of war, alpha status.

In the present condition of the world there is no choice but to maintain defense budgets. of these astronomical proportions, and this need will probably persist until a mechanism is found to reduce paranoia all over the world more or less simultaneously. However, to date there have not been many acceptable alternatives to defense, at least not to the vast numbers of people who would have to be convinced of their efficacy.

Nevertheless, as much as defense spending has disrupted the community of man, the technological development that occurs as a result of such hostility-based expenditures must be given its due for the many lives it has saved and the human good it has done. The question that must be asked is whether the same net progress could not have come another way, with an increase in the benefit side of the cost/benefit ratio. A partial answer must be "no," as long as the threat of war and worldwide paranoia feed the impetus to make war.

The last principle of the Preamble, the insurance of domestic tranquility, is the other principle, in addition to defense, that tends to promote the status quo—the stability—of communities. Tranquility differs from defense in being a positive rather than a negative approach to life. It is the other side of common defense, the community stability coin. Probably for that reason it has been hard to define, much less to implement.

There seems to be something fundamental in human perception that makes negative logic easier to understand than positive logic. An obvious example in high technical application is the null balance indicator and the null hypothesis of statistics. In either case the logic dictates that what is observed are differences that are "not different" from zero. The assumption that two observations are the "same" is not susceptible to the conventional logic of statistics.

The three-year old that uses the word NO repeatedly has simply discovered that the word NO is a control device that is extremely effective. The word YES under such circumstances would not even receive attention, but with the word NO the three-year old is in charge. The defense arguments are similar. "If we do not have strong defense we shall be defeated." The positive, of course, is, "If we have a strong defense we shall be victorious." This transfers the concept to offensiveness and aggression.

The arms race has been couched in the same negative terms—if we do not do such and such, the enemy will do so and so. Fear and anxiety are negative emotions, and they seem to go along with the negative approach to defense strategy; fear and anxiety are used as PR tools in the debates over budgets. If we do not do so and so, such and such catastrophic events will occur. The ultimate progression of this process is the balance of terror—which is simply a null balance device...side A has X power; side B must have X power so that the net is zero—the null balance.

To insure the domestic tranquility then is to pursue the positive side of man's being. This results in a stable society that encourages creative diversity rather than one that buys ease of social control through insistence on conformity. As a matter of fact, the pursuit of domestic tranquility promotes diversity among the individuals of communities and as it does in all biological communities, diversity promotes the stability of human communities.

One of the simplest approaches to domestic tranquility is in terms of recreation. The tendency is to think of recreation as the thing one does in leisure time—the vacation trip to the mountains, the tour of the national parks, or various afterwork activities such as sports. This in spite of the fact that recreation, as a word, has such vital roots. In the context of promoting the domestic tranquility, the concept of recreation takes on important new meaning. It involves the well-being of man, the way time is spent to accomplish well-being, and it's correlates—comfort and security.

If the activity time of man is envisioned as a pie diagram, then recreation is that time necessary to complement work, sleep, eating, etc. All work and no play not only make Jack a dull boy, but may seriously impair his health and well-being, subjecting him to numerous systemic dysfunctions, heart disease, stroke, mental illness, and somatic illness produced by hormonal-induced psychic imbalances.

Recreation is not luxury activity; it should not be restricted only to those able to pay for it; it should be available in a wide variety of forms in almost all places. Viewed in its widest context, recreation complements work in providing the environmental circumstance for the full realization of the genetic potential of man. Activity and productivity are not related only to work. They are the combined products of work and recreation. To interpret the word literally—RE-CREATE—means what it says: to make new, to regenerate. The implication is quite simple and true—that man physically and mentally wears down and out. His nervous system, particularly his musculature, require exercise, change of pace, and challenge. Physical exercise is a direct necessity for mental health. In making the assessment of the value of so-called leisure activities and recreation of no matter what scope or intent—from do-it-yourself construction projects to wilderness back-packing—the benefits that must be evaluated against the costs are increased health, increased productivity, and lowering of social dysfunctions such as crime. Men do not live by work alone, but by an admixture of all that balances the energy flow through his own body with his nutrient intake, enhances his musculature development, and the contributions to the full realization of his physical and mental power. (Critical mental activity is significantly enhanced by physical fitness. The administrator-negotiator to be effective has to train like an athlete.)

The physical and biological environment of man provides the simplest and most direct access to recreation. The fitness of the environment for the activities of man will depend largely upon how man perceives the environment and how he reacts to it. It is not accidental that well-ordered environments characterized by the properties of well-ordered ecosystems provide the optimal opportunities for recreation. It follows that in a well-ordered ecosystem of which man is part, tranquility will be a principal feature.

This is how recreation has to be interpreted. It is in this way that tranquility must be related to the recreational activities of man. To be sure, tranquility is not limited to just recreation but must permeate all the activities of man. However, it is in the area of recreation that tranquility is the most easily perceived and, consequently, the best understood.

The viewpoint must be holistic. It can be no other way. The whole man must be served or the whole man will perish...by pieces, perhaps, but he will perish. (Some of the ugly "pieces" are very much on display in our inner cities right now.)

Longevity, contentment, felicity, well-being, serenity, comfort, the positive sense of achievement and of creativity, are fed and nurtured through these processes. To provide these properties in man to their fullest, recreation in the fullest must be provided to all citizens, and must be guaranteed under the equal protection of the law. This is the true meaning of domestic tranquility.

The founding fathers had a picture of America as strong and vital and creative. The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights are brilliant and universal testaments to their faith in a strong and free America. It is no accident that domestic tranquility was seen by them as among those principles necessary to form a government among free men. In the long run, it provides the basis for all principles they named.

Justice is seldom served in times of stress and anxiety; court records are numerous that point to mass injustices due to paranoia-inducing environmental circumstances (the internment of the Nisei comes to mind immediately).

The common defense is best mounted by a nation that is not only physically strong but mentally committed to creative thought and the freedom that inspires it. And, of course, the common welfare would be greatly aided and abetted in an environment that promoted the opportunities for the total well-being of man.

The promotion of domestic tranquility, then, is a community-related factor that has the ecological property of promoting the stability of communities. Since it is directed at bringing about community change by evolution rather than revolution, it supports the status quo.

Of all the methods to promote community health and solidarity, creativity and well-being, the promotion of domestic tranquility has the largest unused potential of all the major tenets of our governmental systems. At present it is the most under-exploited mechanism we have to create the ideal quality of life for man and for all the multitudes of biotypes which share the biosphere.

A quick examination of the Federal budget will indicate the following expenditures for the four topics of our discussion.

| * | Justice: | 1-3 billion |

| Defense: | 190 billion | |

| Welfare: | 14-6 billion | |

| Tranquility: | 1300 to 500 million | |

* Including the Federal Judiciary | ||

We have previously noted that justice, defense and welfare have been structured as major organizations of the Federal government. Domestic tranquility, while equally important, has not been identified at a major organizational level. As a matter of fact, at the Federal level it exists only in bits and pieces of several bureaus in several Departments. Parts of the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Fish and Wildlife Service contribute in this area, and the entirety of both the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service and the National Park Service. Of all agencies involved in domestic tranquility, the National Park Service is the most strongly identified in the area and has the clearly exercised leadership. But our best national effort for domestic tranquility is meager when compared to the need. It is neither surprising nor alarming, however, since it has been only in the recent decade and a half that enough understanding has been gained of the environment, the ecological principles that govern it, and its relationships to man to apply this understanding to insuring the domestic tranquility.

It is not "too late." As a matter of fact, it is never too late. What better time can there be to rededicate ourselves to the great principles stated by the founding fathers in the basic law-giving instrument of the United States—the Constitution—than at the beginning of our third century of existence as a free nation?

Since the domestic tranquility is community-oriented, it can readily utilize large amounts of wealth without creating revolutionary changes in society. Change will occur, but it will be predictable, orderly, and evolutionary in nature. Increased increments of future wealth production can be dedicated to domestic tranquility with the full realization that our economic system will not only be stabilized, but will grow in an orderly fashion. Justice will be served, since increased social and economic opportunity should reduce crime. Defense will be served, since the benefits of tranquility will be strong moral and physical fiber and a sense of dedication and rededication to the principles of liberty and freedom and the rights of man. The nation as a whole can be transformed ecologically, biologically, morally and economically into the land of the free and the home of the brave, where the quality of life of all citizens can be improved to such an extent that we can truly say we are evolving to the humane society.

How Does Domestic Tranquility Work?

An attitude of calm strength on the part of the United States should go a long way toward introducing the concepts of domestic tranquility to the whole troubled world, both at home and abroad. It is, after all, the fruits of domestic tranquility that make the country worth defending.

The exploitation of this potential for community-building among men has direct and immediate application at all levels of government and in every sphere of man's activities. It will be most instructive to examine the properties of the principle of domestic tranquility through a broadened concept of recreation—that activity which is the necessary complement of the labors of man if man is to enjoy the comfort, security and well-being which is the birthright of every man, woman and child in the biosphere.

The basic premise of this argument is that future wealth production is logarithmic and in the long run will continue to increase. It further postulates that some of the new wealth (in the public sector particularly) could and should be dedicated to those activities that promote the status quo (our form of government) with evolutionary change and will be used to discourage revolutionary change.

The premise further elaborates that the common defense and domestic tranquility, of all the basics for government, best fulfill these purposes and that to the present it has been defense spending (because of the of man's beta paranoid outlook and because of the effect defense spending has in supporting this status quo) that has best served that need. Since man's paranoia is based upon real threat, there can be no diminution of our preparedness. No argument is being advanced that the defense budget should be reduced in favor of any other program. What is being argued is that as resource information continues to produce further incremental wealth, some of this increased increment from future revenues and in future budgets be dedicated to domestic tranquility.