|

MEANINGFUL INTERPRETATION An Interpretive Dialogue |

|

|

"THE TRUE SPIRIT OF CONVERSATION CONSISTS IN BUILDING ON ANOTHER MAN'S OBSERVATION, NOT OVERTURNING IT." —Edward Bulwer-Lytton

|

1

Discouraged, the interpreter pushed herself away from her computer and headed toward the park. The town was dark except for the street-lights. She stopped at her favorite places, but found nothing to lift her spirits. She felt even worse when she discovered a stranger sitting on her bench.

"Can I help you?" the stranger asked cheerfully.

"I work here. Can I help you?"

The man smiled, "Tell me what you do?"

"I'm an interpreter?"

"What does an interpreter do?"

"I give programs to visitors," she answered automatically.

"You talk to people... is that it?"

"It's not easy. Lots of them don't listen?"

"So why do you do it?"

The stranger was about 60 years old, and wearing an old blue suit. He was bald with tufts of white hair around his ears and a bright pink complexion with plump cheeks. A pair of black framed glasses perched on his thin nose.

"I do it because people should realize this place is important. It's too bad so many won't stop long enough to learn about it?"

"Why should they?"`

"Because it's special. I wish I could make everybody see why?"

2

The interpreter sat down on the bench and asked the stranger his name.

"I am Harold Durfee Nedlit," the man enunciated. "A professor of philosophy. It is a special place, but do you really think everybody has to learn about it?"

"No, but parks are meaningful places and I don't want that forgotten!"

Nedlit leaned forward. "Parks mean something? What do they mean?"

The interpreter hesitated, "They mean lots of things?"

"Are these meanings tied to the place?"

"What?"

"Can meanings be separated from places?"

"I've never thought about it?"

"It's fundamental. How can you describe your work if you don't understand the relationship between your place and what it means?"

Nedlit paused. The interpreter said nothing.

"All right, this might help," Nedlit began. "In the Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln said, 'We can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.'

"Now if Lincoln was correct, all Gettysburg could become a shopping mall and not change the meanings of what occurred there. Do we really lose anything if we lose the place? You can learn all about the Civil War from books and photographs. Why visit or care about places at all?"

"Because the place is powerful. Without the place, meanings would be harder to find and describe to get people excited about — harder to interpret. Without the place people will forget the meanings?"

Nedlit nodded, "Lincoln saw the importance and power of place. His speech ends by demanding the audience embrace meaning and take action. 'It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work'...

"Lincoln might say places or resources are icons or windows to meanings. Each is a symbol or metaphor for a world of concepts and emotions. In day-to-day life it's hard to recognize and concentrate on these meanings. But resources provide focus. Each place has its own story or beauty — how it speaks to people about meaning. Some have obvious and striking power — other places are subtler.

"So, I ask you again, why do we have parks?"

"They are places that give people access to meanings," the interpreter replied.

"Yes! Resources possess meanings and have relevance."

3

The interpreter thought a moment, then objected, "But so many people miss the meanings?"

"Ah — so why do they visit?"

"To have a good time?"

"Is that all?" Nedlit demanded, "They can enjoy themselves almost anywhere. What are they looking for in a resource?"

"Something special. Something of value for themselves?"

Nedlit continued, "Even people who want to motorboat on reservoirs and drink beer?"

"Yes, they're not in the office or working a job they hate. But that's my point, they need to have more than just fun?"

"You want them to find meaning?" Nedlit asked.

"Sure?"

"I said resources possess meanings and relevance and you agreed. Then you said visitors are after something of value for themselves. So what does interpretation do?"

"Obviously bring the two together."

"Do you really believe that?"

"Why wouldn't I?"

"Because you said 'I wish I could make everyone see why this place is special.' You will never make the place special; the place is already powerful and meaningful. But you can help connect visitors' interests with resource meanings. That's your job."

The interpreter stood up. "Fine, but it's more complicated than that," she said, "You should come on my program tomorrow and..."

"But don't you SEE?," said Nedlit touching her arm. The interpreter sat back down. "Helping visitors connect to meanings is the entire goal. Meaning is more important than knowing! Your job is not to fill their heads with information. Giving people information when they want it is important, but it's not interpretation. Even those people who want information want to connect it to meanings. Audiences want to connect to your place intellectually and emotionally.

"Your job is not leading people to the meanings you think they should know and feel. Your job is to help people discover their own meanings. When you do your job well, people might come to conclusions you don't agree with. So be it. If people come to care about your park, you've done your job!"

The interpreter countered. "What if they're hurting the park?"

"You need to stop them. But that's not what I'm talking about. I'm talking about what people think and believe. Like it or not, the visitor is sovereign. People get to choose! No matter how much you care, the visitor decides if the place is worth preserving.

"Your goal is to facilitate a connection between the visitor's interests and what the place means. That's how you establish care about the resource. People have to care enough about the place to help care for the place. Care about happens first — attitude before behavior. Why take action to protect something you don't care about? Raising sensitivity — helping people care about is what interpretation does."

4

"Okay," the interpreter said, "people connect with their own meanings.. .but that worries me. I believe in what I talk about. How can I interpret meanings I don't share? Especially if I think, and almost everyone else thinks, those points of view are wrong?"

"Are accuracy and the truth the same thing?" Nedlit asked.

"Probably not. Accurate information can lead people to different conclusions. I guess truth is something people believe in."

"Were you hired to be accurate or provide the truth as you perceive it?"

"I know I can't present my opinion — no matter how much I believe in it — and call it the only truth. But some things people believe in are crazy"

"So describe other points of view accurately, even if you don't agree. Whose job is it to decide the values and meanings of the resource, the interpreter or the visitor? Do visitors have a right to their own beliefs?"

"The visitor is sovereign," the interpreter smirked.

"Then present accurate descriptions of alternative points of view and let the audience judge. If you helped people care about the place, they'll see something should be done to protect it.

"I know you can't cover every possible perspective. You have to choose relevant material that provokes your audience. But you better know enough about your subject to respond thoroughly, respectfully, and professionally whenever an alternative view arises. Good interpreters don't create fiction — they accurately present the multiple meanings of the resource to multiple audience perspectives. This shows respect for the audience, and that makes dialogue possible. Of course you have to know a lot about your place and audiences."

The interpreter raised her voice, "But I do this work because I have passion. I want to save the place"

"Do you have enough passion to help visitors develop their passion?" Nedlit asked. "If not, you'll only communicate with people who already agree."

"But I need to get the preservation message across."

"So earn the right to deliver that message. Meet visitors where they are and help them make personal connections to the resource. The visitor who wants to drink beer and the pilgrim on a quest both contribute to the park's survival. They can each come to care more about the place. It's that simple, and that difficult. It's difficult because it's easy to preach and fool yourself into thinking you are interpreting."

5

Nedlit was quiet. He looked down and rubbed his head with both hands. As a result, his hair stuck straight out on both sides. Oblivious to the winglike effect it gave his face he squinted towards the interpreter gravely and asked, "What do your parks preserve?"

"Mostly buildings and nature" the interpreter answered suppressing a smile.

Nedlit took out a pad and wrote something. "Is that all?"

"No...artifacts, plants, trees, information, culture, heritage...viewsheds...events...I guess we preserve information about people. And about events too." Nedlit kept writing. "Okay, we also preserve ecosystems and natural processes like glaciation. We preserve animals, wilderness, and objects..."

"What about ideas? Do you preserve ideas?"

"Ah...yeah. You could say we preserve the idea of democracy. We also promote the idea of preservation."

"You said you preserve systems and you supplied some natural examples. What about cultural examples — say the system of slavery?"

"We don't preserve slavery itself, but we do preserve information, objects, and buildings that are, as you say, icons of slavery."

"Yes. What about values? Do you preserve the values that supported slavery?"

"I hope not. But we do preserve information about those values."

"What about other values?"

"We preserve things and ideas that people value like beauty and freedom, to name a few."

"Very good." Nedlit showed the interpreter two lists.

|

Buildings Artifacts Plants Trees Ecosystems Wilderness Objects Information Events |

Nature Culture Heritage Values Systems Wilderness Process Ideas Knowledge |

"Now" Nedlit demanded, "what's the difference between these two lists?"

"One is real things and the other lists abstractions."

"Natural sites are places where the beauty, order, and the power of nature are focused in a tangible location. Cultural and historical sites are also real locations where visitors seek the energy and effect of events and people. Both are physical manifestations of meanings — and all their objects: trees, stone, water, fences, monuments, and furniture — they all connect an intangible meaning to a physical reality.

"At its most basic and important level, interpretation links tangible resources to their intangible meanings. All successful interpretive work — talks, walks, signs, exhibits, videos — make these links! When they are most successful, tangible/intangible links go beyond words and visitors experience meanings in a personal and often indescribable way.

"But you included wilderness on both lists."

"I did that because I don't want us to argue about which list it belongs on. Some people see wilderness as a real and specific place. Others see it as an abstract idea. Interpreters have to understand and communicate both meanings.

"It might seem a little complicated at first. In its simplest form, a tangible resource is a specific object, place, or person. But a tangible resource can also be any group of those tangibles, like all wilderness or all battlefields or the Navajo people. In larger groups, the tangible resource becomes more abstract. Nevertheless it can be used as the tangible, the thing the interpreter wants the audience to care more about."

"So I could use a specific place that is wilderness as an example of all places that are wilderness?"

"Exactly. Or you could use that place to provoke intellectual and emotional connections about the intangible meanings of wilderness. But let's think about tangible resources for another minute. You can also consider events and people from the past as tangible resources, the suffragette movement for example or, John Adams."

"How can I preserve something that doesn't exist anymore?"

"You do it all the time. Why do you tell stories about the people who lived in this town? What's the point?"

"I want them to be remembered."

"Of course! That's all you can do to preserve them — and take care of the things they created and lived with."

The interpreter considered this, then smiled. "Remembering is an act of preservation!"

"And not just for human history. Natural events like rock slides or geologic periods can be tangible resources as well."

Nedlit stood up abruptly. He walked over to the trash can and pulled out an empty beer bottle.

"This will do. We'll start simple." he said. "I want you to tell me what this tangible object means. Show me the links."

The interpreter tried. "It's made of glass, it's brown, it's got a label — it's empty."

"It's all those things. "But don't you SEE?" Nedlit moved closer. "You're giving me information. You're describing this bottle. I asked you what this bottle means."

The interpreter tried again. "Good times. It represents all sorts of things in our culture like parties, friends, and relaxation."

"Is that all?"

"No...I can use the bottle to talk about alcoholism and prohibition and self-help groups and twelve-step programs."

"Yes, go on."

"Ah, I can talk about advertising and glass making. I guess I can talk about trash and recycling. I can talk about the history of brewing. I can also talk about the person who actually drank the beer out of that bottle."

"Yes, yes. Are any of those links incorrect?"

"Incorrect? They're just different perspectives on the same object."

"I agree. All of those are intangible meanings associated with that bottle. Let's take another step and try a model."

6

"Here's a horizontal line." Nedlit showed the interpreter his pad.

TANGIBLE: INFORMATION, NARRATION, CHRONOLOGY, FACTS

"How much interpretation adheres to only the information and the narration? How many programs stay on this horizontal line?"

"Way too many — some interpreters just give information."

"Now a vertical line." Nedlit handed over the pad.

"How many programs have you seen that stay on this vertical line?"

"I've given those — too many concepts and abstractions. I could see visitors' eyes glaze over."

"Think of art as an analogy for tangible and intangible relationships. Blueprint drawings are the tangible. They illustrate information. Good blueprints are important. But by themselves, unless you are an architect or a builder, they don't move the soul.

"Abstract art represents the intangible. Lots of people fail to see the artist's intent. They don't have the background to understand the meaning of the piece. Most people need art that is recognizable, but is somehow moving, meaningful, and even memorable..."

The interpreter interrupted, "So it's about the link! A program that is mostly information bores visitors to tears. A program that is too conceptual confuses. Successful interpretation depends on a linkage of the tangible resource and its intangible meanings."

"Can you give me an example?"

"Living history Visitors love it because it's so tangible. It connects them to a battlefield that is largely intangible — so difficult to imagine in all its horror — it's too abstract and removed. Living history gives us colors and brass buttons and drawn swords. But too many living history interpreters just talk about the tangible. They can tell you about the buttons, but give you very little meaning."

"What about a natural example?"

"You could say the same thing about live animals and spectacular rock formations. They attract attention, but if you don't go farther than providing a catalog of information about them, there is little meaning involved."

7

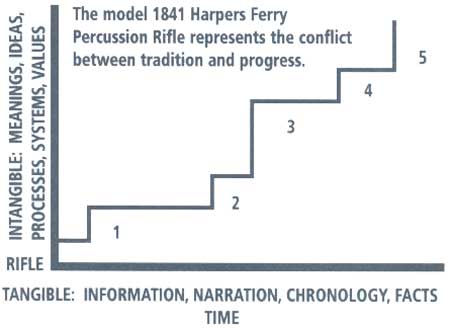

Nedlit nodded and cleared his throat, "Imagine that I am giving an interpretive talk and have an old rifle in my hands.

"This is a model 1841 Harpers Ferry Percussion Rifle. In the 1840s, it represents the very essence of modern times because of its technology. It was made entirely by machine and with interchangeable parts. It loads from the muzzle and is a rifle. A rifle has grooves cut into the barrel that send the ball out with a spiral, just like a correctly thrown football. This gives the weapon great accuracy.

"The rifle fires with a percussion system. There is no flint and steel, no spark or flash outside the weapon as there was with the flintlock system that preceded it. The hammer of this rifle strikes a small percussion cap, shaped like Abraham Lincoln's top hat. A bead of explosive located in the top of the brass cap ignites when it's hit. This begins the process that sends the bullet on its way.

"I like to think about the human hands that made this rifle because it also represents modern times in terms of the way people lived. Occasionally I imagine the parlor of one of the workers. I think of him living with a large family that includes his father. I like to listen to their conversations.

"'In my mind', the father often says 'Son, you have lost the meaning of 1776. I was a craftsman. I worked eight years as an apprentice to gain the knowledge and skill needed to make an entire rifle with hand tools. I owned those tools. If I didn't like the way I was being treated in the factory, I could move away and set up a gun shop anywhere. I had freedom. I controlled my own destiny. I was proud. But in your wildest dreams you will never own the machines it takes to make a rifle now. The day the men who own those machines decide they no longer need you, you'll be gone. You've become a slave to those machines, not a free man.

"The son responds, 'But I'm making more money than you ever could. My home has carpet, my children go to school, I own books, and buy newspapers. You could only afford to buy us things we had to have to stay alive. No father, I understand what 1776 was about. I am as free as a man can afford to be.

"Of course they never understood each other. This leaves us with a question. We can ponder this rifle, an object made of cold metal and dead wood, and ask ourselves how in our own time we respond to the father and son's same challenge — the conflict between tradition and change."

Nedlit held up his hand and the interpreter remained silent. He wrote on his pad for a few minutes, then passed it to her.

The interpreter studied the pad for a few minutes, then said, "I need an explanation."

"You've probably noticed I have set up an x, y axis."

The interpreter grimaced. "I hate math"

"Bear with me," Nedlit said with a chuckle. "I graphed the opportunities for connections to the meanings of the resource. An opportunity for a connection to meanings is a tangible/intangible link developed by an interpretive delivery method — a story, presentation of evidence, quotes, illustration, or other presentation technique.

"I added 'time' to the horizontal or tangible line for the time required to present my program. The rifle is the main tangible."

"What about the father and son and their house?" asked the interpreter?

"You're right. I want my audience to care about the Industrial Revolution as an event, as well as the people who lived through it. The father and son were vehicles for telling that part of the story. I also want my audience to care about more than just this one rifle; I hope they see it as symbolic of other weapons from the period. And surely I want people to remember the rifle came from Harpers Ferry — the tangible place that preserves the rifle's story.

"All of these are tangibles, but the icon that allows me include them is the rifle. It's the specific starting point and through line that makes the whole program go."

"But the rifle isn't even here. How can you claim it's tangible?"

"Because it's an easily recognizable object. We both knew what I was talking about.

"The graph illustrates some of the tangible aspects of the rifle, its information, as well as some of the intangible meanings of the rifle. The vertical lines depict the tangible/intangible links. My talk also provided information through interpretive delivery methods that elaborated on or 'fleshed out' those tangible/intangible links. The horizontal lines depict that information. The links and information together provide opportunities for the audience to make personal connections to the rifle.

"I started with basic information. The horizontal line that begins near the meeting of the two axis represents that information. The first time I linked the rifle to an intangible meaning was when I made the statement, 'In the 1840s, it represents the very essence of modern times because of its technology.' That's Number 1 on my graph. It labels the vertical line that represents my first tangible/intangible link.

"Then I developed the link with an interpretive delivery method. I made a presentation of evidence about how the weapon represented modern times for technological reasons. The horizontal line above the 1 represents that information. Then I linked the weapon to the people who made it — see Number 2. I provided just a bit of information about one gun maker's living arrangements.

"The third link came when I tied the rifle to the intangibles of craftsmanship and one definition of freedom. I developed the link with the character of the gun maker's father. He conveyed information about craftsmanship and freedom. Then I linked the intangibles of affluence and a differing definition of freedom to the gun at Number 4. The son provided the interpretive vehicle for information about the Industrial Revolution and some of the attitudes toward freedom that developed with it. Finally, with Number 5, I linked the weapon to the conflict between tradition and change by asking the audience a rhetorical question.

"The graph is just a tool. It can help organize programs and specify opportunities for connections to the meanings of the resource. You can also use the graph to track how an interpretive program develops an idea. I want each opportunity I present to provoke visitors. But I have to arrange those opportunities for connections to meanings to say something larger about the rifle. If I do it well, visitors will think and feel about the rifle differently."

"What do you mean 'something larger'?" the interpreter asked, looking puzzled.

8

"A successful interpretive product cohesively develops an idea or ideas about the resource. It's not enough to provide related information or even disjointed meanings. Interpretation says something, expresses an idea. A series of facts or a chronological narrative just doesn't provide enough relevance to connect enough people to the place. A compelling idea does. All the parts of the program have to work together to develop that idea so the audience can make personal connections to the meanings of the resource."

"You're talking about a theme. It's there on your graph."

"You're right," Nedlit agreed. "An interpretive theme statement links the tangible to an intangible and expresses an idea. My interpretive theme statement was 'The model 1841 Harpers Ferry Percussion Rifle represents the conflict between tradition and progress.' I used that theme to select my links and develop them into opportunities for connections to the meanings of the resource. I arranged and sequenced those opportunities to articulate and explore my theme statement. But that doesn't mean the theme statement is a 'take-home-message.'"

The interpreter's face still expressed confusion.

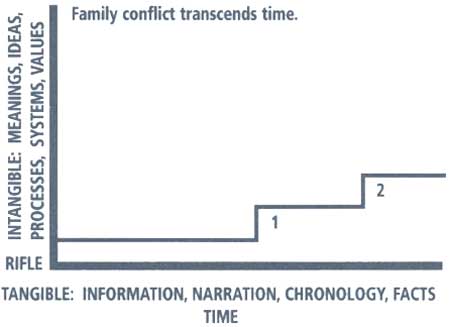

Nedlit continued. "Think about the graph another way. I used a graph to plan my talk. But hypothetically you can also graph the personal connections each audience member actually made through the delivery of the program. I'm absolutely sure each of their graphs would be different from mine and from each other."

"You're moving too fast, I'm not following."

"My graph showed the links and opportunities for the connection I wanted to offer. But the visitor is sovereign. They process the opportunities I offer through their subjective beliefs, experiences, and circumstances. Hold on a second."

Nedlit started to draw.

"The visitor who drew this graph was bored by the technology of the rifle The last link about freedom didn't work either — likely too patronizing. My theme statement didn't connect exactly with this visitor nor did all of my links and opportunities for connections to meanings. But this person made personal connections through the father and son. This visitor might say the program's idea was: 'Family conflict transcends time.' That's different from my theme statement but includes much of its content as well as the personal elements brought to it by the visitor."

"You're saying that's okay?" the interpreter asked.

"Yes. Interpretation is art. When you look at a painting, you have your own relationship to the work. You find your own meaning or you don't. Your understanding of the meaning of the painting may overlap with the artist's intent, but it won't coincide exactly. If the piece works it's partly because you see personal meanings the artist was never aware of. A good interpreter tries to say something important, but knows that ultimate success happens when the viewer connects the message with his or her own experience."

"You're telling me that the audience doesn't need to get my theme. Hey, I'm happy to drop the theme altogether."

Nedlit answered with a smile. "But don't you SEE? — of course you need a theme! How else will you know what you're trying to say? But you also need to know the audience doesn't have to walk away with your theme statement burned into their minds. Look, themes are tools just like organization, grammar, body language...all artists have tools. A painter learns about color and perspective before the masterpiece is on canvas. A concert cellist practices scales but performs music.

"No interpreter gets very far without tools. Tangible/intangible links and the information that explain them are the vehicle interpreters use to reveal and provoke. But you have to use good techniques to present them. Any interpreter can ruin a perfectly good link by delivering it poorly."

9

Nedlit wasn't finished. "There is more to linking the tangible to its meanings. Are all meanings equally powerful?"

"No. The visitor is sovereign. Some links work better for some people than others."

"What was most meaningful to you in my talk?"

"Freedom...and I was thinking about fathers and sons fighting."

Nedlit leaned back, "Now what do freedom and family have in common?"

The interpreter said, "Just about everyone can connect with them."

"Exactly. You can label a whole group of intangibles 'universal concepts.' They're relevant to almost everyone."

"But not everyone will agree on what family or freedom means."

"They don't have to. Though all people have widely different points of view about specific universal concepts, the concepts themselves are relevant to almost everyone.

"Yeah — my best programs — the interpretation that works every time, they're about concepts like beauty, race, change, family, spirit..."

"Give me more."

"Power, pain, ah...probably nature itself, God, survival, love, sex, hate, sacrifice is another, maybe bravery and cowardice. The list could go on. Whoa! It's like mythology."

This time Nedlit interrupted, "Or the Bible, or the Koran, or Shakespeare, or even soap operas. We're talking about the questions and forces and forms of the universe. Some call them archetypes. Universal concepts are the stuff people have been making stories about and trying to figure out since the beginning of human history. They're the intangible meanings that are most relevant to the most number of people — meanings few people agree on, but most everyone cares about."

"How could all cultures and people relate to these subjects?"

"You're right, 'Universal' is probably too big a word, but I don't have another. I'm sure some of these concepts are more meaningful to some people than others. What's important is some concepts are more effective for interpreters because they're more relevant to more people. We could argue whether a given concept is universal or not but in the end interpreters have to decide for themselves."

"I can see how this works for history There's so much human to talk about."

"Think about it! Since humans began to think about nature as something worth conserving, writers, speakers, and interpreters have been connecting plants, animals, fossils, and features to intangible processes, ecosystems, ideas, values, and universal concepts.

"Universal concepts like beauty, time, harmony, power, complexity, survival, sex, and change are powerful and at the very center of good natural history interpretation. A universal concept like family has a different meaning in cultural or historical contexts, but it allows humans to communicate about and explore those differences."

10

Nedlit worked on his paper, then handed it to her.

| TANGIBLES | INTANGIBLES | UNIVERSAL CONCEPTS | ||

|

BUILDINGS ARTIFACTS PLANTS TREES ECOSYSTEMS WILDERNESS OBJECTS INFORMATION |

NATURE CULTURE HERITAGE EVENTS SYSTEMS WILDERNESS PROCESS IDEAS VALUES |

FREEDOM FAMILY RACE POWER GOD HATE SACRIFICE BEAUTY CHANGE |

He said, "You can use those lists to develop any interpretive product. You need to make the lists specific to your resource first. Right now those words are abstractions, but if you select a tangible from your place and then brainstorm all the potential intangible meanings that could be linked to it..."

"Like we did with the beer bottle."

"Yes. You should have a pretty long list and some of those links would be to universal concepts. You still won't have a program. You'll need to decide specifically what that will be about."

"I'll need a theme statement so I can cohesively develop an idea."

"You've got it. Here's something new though," Nedlit warned. "I said earlier that themes link a tangible to an intangible. The most powerful themes do that by linking the tangible to a universal concept. That kind of theme will help you choose other links that support the theme statement. Not all those links have to appeal to a universal, but they should help the development of the program's main idea that does have one.

"And then use interpretive techniques and methods to develop those tangible/intangible links.

"Turn them into opportunities for the audience to make their own emotional and intellectual connections to the meanings of the resource you're interpreting."

"Yeah," the interpreter responded and then fell silent. Finally she said, "It's scary."

"You said the place was important."

"I still can't prove why."

"You won't prove the importance of this place to everyone. You will create opportunities for people to realize it on their own.

"Interpreters are artists and teachers. They allow others to find their own meanings. Their art expresses, but it also communicates. When you are an artist and a teacher, not an entertainer or spokesman, when you deal with meanings relevant to your audiences, you move people to care. You hold influence and power. You don't change all the attitudes you hope to, but you affect far more than you realize."

Again there was silence. Eventually Nedlit spoke, "Really, these aren't new ideas. Everyone struggles for meanings and everyone wants to communicate. This tangible/intangible model is just your description of what interpretation does. It won't work for everyone. Others can find other descriptions just as powerful and useful; they'll also find those descriptions in themselves."

Nedlit and the interpreter sat on the bench, a place she had known for years. There, she had discussed a hundred different programs and talked with thousands of visitors. A nail was working up out of the wood. The interpreter pressed it with her thumb. Suddenly she raised her head and looked Nedlit squarely in the eye.

"When will you be back?"

Nedlit smiled, "But don't you SEE? The next time you need me."

©2003 Eastern National. Eastern National provides

quality educational products and services to America's national parks

and other public trusts.

ISBN 1-59091-019-2

meaningful_interpretation/mi1.htm

Last Updated: 29-May-2008

Meaningful Interpretation

©2003, Eastern National

All rights reserved by Eastern National. Material from this electronic edition published by Eastern National may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of Eastern National.