|

John Day Fossil Beds

Ancient Life and Landscapes |

|

Ancient Life and Landscapes

John Day River Valley

A unique treasure is concealed in the sculpted exposures of sedimentary rock of the John Day River Valley in central Oregon. Here are some of the richest fossil beds in the world, and they contain a record of remarkable continuity. Fossil Beds that span even 5 million years are rare. Yet in this valley the fossil record shows more than 40 million years of the diverse plant and animal life that existed here 45 million to 5 million years ago. R.W. Chaney, a paleobotanist, once wrote that "no region in the world shows more complete sequences of tertiary land populations, both plant and animal, than the John Day Basin." It is a record of such continuity and duration that scientists can test theories against the fossil record.

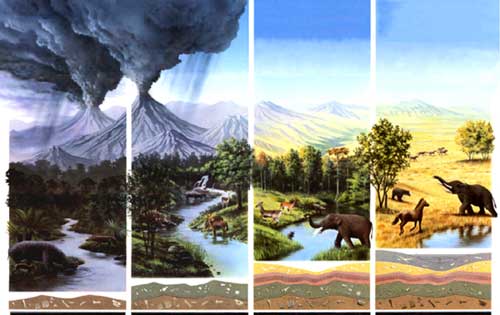

Fossil beds contain vestiges of the actual soils, rivers, ponds, watering holes, mudslides, ashfalls, floodplains, middens, trackways, prairies, and forests. The rocks are rich with the evidence of ancient habitats and the dynamic processes that shaped them; they tell of sweeping changes in the John Day Basin. Great changes, too, have taken place in this area's landscape, climate, and in the kinds of plants and animals that have inhabited it. And it is all recorded in the fossil record. Four of these major environmental periods are depicted in the next four Web pages.

|

|

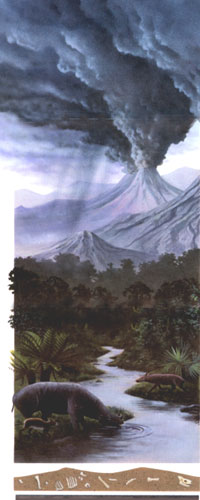

Clarno Formation

54 to 37 million years ago Tropical subtropical forests mantled the local terrain 54 to 37 million years ago. We know of these forests because of a splendid sample of fossil seeds, nuts, fruits, leaves, branches, and roots. The Clarno Nutbeds are among the finest fossil plant localities on the planet, with hundreds of species -- many new to science -- preserved. The conspicuous mammals were the browsing brontotheres and amynodonts -- conspicuous because of their great size and ungainly appearance. Impressive, too, were the strong-jawed scavengers, hyaenadonts, and ruggedly framed predators such as Patriofelis. Although a few of these animals lived into the early Oligocene -- 34 million years ago -- they have left no modern descendants. However, some of their contemporaries -- the equids, rhinos, tapirs, and cats -- do have present-day descendants, most of which are no longer found in North America. |

|

|

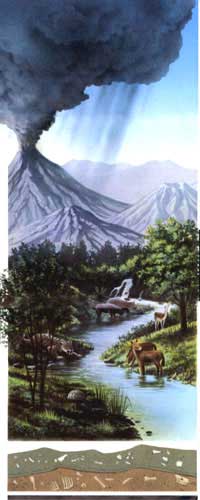

John Day Formation

39 to 20 million years ago The John Day Formation spans almost 20 million years. Even a cursory examination reveals that many types of environments existed in landscape. Deciduous forests replaced the earlier subtropical forests of the Clarno Formation. Number fossil plant localities containing a great number of different species indicate the vast biological diversity of the early Miocene Epoch. More than 100 groups of mammals have been found in this formation as well, including dogs, cats, swine, oreodonts, horses, camels, rhinoceroses, and rodents. Multiple volcanic events during the deposition of the formation produced large amounts of volcanic ash. The resulting tuff, interspersed throughout the fossilb-bearing beds, allows determination of accurate radiometric dates. The chronology derived from the tuff helps scientists determine the rate at which plants and animals changed as they evolved. |

|

|

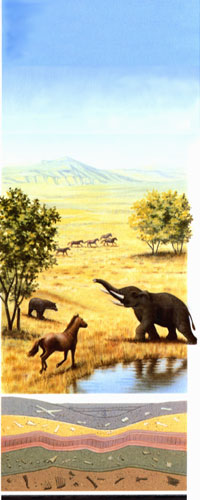

Mascall Formation

15 to 12 million years ago The interval between deposition of the John Day and Mascall times was marked by intermittent flows of basaltic lava that repeatedly leveled and denuded the region. By 15 million years ago these eruptions had ceased and the basalt was weathering into soil. A moderate climate, sufficient precipitation, periodic deposits of volcanic ash, and the basaltic parent material combined to produce highly fertile soils, and from these soils arose lush, nutritious grasses and mixed hardwood forests -- much like those found today in the eastern United States. The Mascall savanna was home to a great variety of animals that we might recognize as horses, camels, and deer, as well as bears, weasels, dogs, and cats. Some dwelt in the woodlands, while others adapted to the grasslands. At the same time large mammals made a resurgence. Among them were the gomphotheres (early elephants), as well as sizable rhinos and bear-dogs. |

Illustration by Rob Wood based on research and artwork by Doris Tischler. |

Rattlesnake Formation

8 to 6 million years ago Named for Rattlesnake Creek, a minor tributary of the John Day River, the coarse deposits of the Rattlesnake Formation complete the paleontological story of the John Day Basin. Tectonic pressures from the south and north folded and buckled the rock beneath and around the base of the Strawberry Volcanics, eventually thrusting the modern Strawberry-Aldrich mountains upward as much as 1.5 miles above the John Day Valley. As the mountains rose and eroded the valley was slowly filled with deposits. These strata represent the last major episode of deposition in the basin. Erosion then began and continues to sculpt the landscape of today. The interface between the Mascall and the Rattlesnake formations is easily distinguishable to geologists and paleontologists because the nature of the materials in the two sequences are quite different. It is somewhat subtle to the untrained eye. The most spectacular clue is best seen from the geologic exhibit on Route 26, south of Picture Gorge, where a 5% angular unconformity between the formations can be clearly seen. The underlying Mascall beds are tilted at a different, steeper angle than the younger Rattlesnake deposits (formed after a major tilting of the Mascall Formation and lower layers). Within the Rattlesnake Formation is a large, blocky, welded tuff layer. It was formed from a fiery tidal-wave of super-heated volcanic gases and particles from an explosive volcanic source far to the south (perhaps Harney Lake) -- an ignimbrite. This rimrock layer can be seen above Picture Gorge and eastward along the John Day Valley -- relics of this massive volcanic event. This tuff averages 90 feet thick, and yields no fossils. Above this ignimbrite layer are more Rattlesnake Formation erosional deposits. However, here, as deposition from the Strawberry-Aldrich mountains continued, the character of the deposits graded toward finer particles as the nearby mountains wore down. The fossil-bearing strata in the Rattlesnake are often so poorly consolidated that extracting a fossil frequently requires artificial stabilization of the rock to keep it in one piece. The Rattlesnake Formation is of great importance as one of four correlative localities on which the Hemphillian North American Land Mammal Age is based. Though they contain considerably fewer fossils than the Clarno, John Day, or Mascall formations, fragmented fossils have been found of horses, sloths, rhinoceroses, camels, peccaries, pronghorns, dogs, bears, and others. It is an interesting population, with some species resembling those of today and others, those of a distant past. A preponderance of grazing animals over browsers suggests a much dryer and cooler climate, dominated by grasslands. |

Illustration by Rob Wood based on research and artwork by Doris Tischler.

Uncovering the Past

Fossil beds that span even 5 million years are rare, yet in this valley the fossil record shows more than 40 million years of the diverse plant and animal life that existed here 54 million to 6 million years ago. Fossils are common components of the earth's crust. Typically they are tantalizingly incomplete, or may occasionally represent only a momentary environmental catastrophe. In only a few areas on the planet have earthly processes, events, and chance combined to produce such a generous array of information as is found in the John Day Fossil Basin.

The fossils found here are generally very well preserved specimens. The Clarno Nutbeds yield fossilized material with cellular structure clearly visible. The John Day vertebrates are among the best preserved of their type. The fossils also occur in large numbers. The Bridge Creek site yielded 22,000 plant specimens in a single early collection event. The Mascall Formation has provided billions of small invertebrates (mostly small diatoms). Also remarkable is the great diversity of fossilized materials: whole communities, not just individuals are preserved, reflecting rich ecosystems.

All these features are arranged in an unusually ordered sequence. They were deposited during a momentous and interesting time in earth's history, recording an amazing array of evolutionary activities that reveal mammalian adaptive radiation, shifting climates, global cooling, and other nuances of earth's history only sparsely hinted at most localities in the world. The John Day Fossil Beds contain vestiges of the actual soil, rivers, ponds, watering holes, mudslides, ashfalls, floodplains, middens, trackways, prairies, and forests - in short, entire landscapes.

Perhaps best of all, the absorbing time sequence of these fossils is recorded by their interbedment with ashes and other volcaniclastics that serve as time markers. The many datable layers allow correlation with other formations throughout the world. The result, earth historians can receive detailed corroboration or falsification of hypotheses about transformation of climates, life-form lineages, and ecosystems throughout broad spans of time.

Exploration and study of the John Day fossil beds continues today. In many of the beds, the fossils are widely scattered, and their occurrence cannot be predicted. Fossils deteriorate rapidly once erosion exposes them to the elements. Thus the fossil beds are continually canvassed according to cyclic prospecting schedules. Sites that weather rapidly are revisited more frequently.

Prospecting conducted by the monument's staff results in the collection of hundreds of specimens each year. Many are mere fragments - a few teeth, for instance, but each specimen is accompanied by a wealth of field data: coordinates that pinpoint both its geographical location and the stratigraphic position, descriptions of where it was deposited, and data about its recovery. This information, as well as that gained as the fossil is stabilized, prepared, and studied, is entered into national museum files.

Such comprehensive collection efforts provide researchers with scientifically significant samples, which open up intriguing avenues for research. Paleontologists can now detect subtle shifts in the composition of the ecosystems through time. Researchers have identified and studied some ancient soils preserved in the John Day Basin and, from a distance of millions of years, are able to gauge former climatic conditions in significant detail. Sedimentologists map the orientation of bones in a Clarno Formation quarry, and thereby plot the eddies, backwaters, and gravel bars of a river that flowed 37 million years ago. Paleobotanists determine the rate at which plant communities evolved. A biostratigrapher dates the last known occurrence of a fossil primate in North America. Studies such as these, representing many scientific disciplines, combine to give us richly detailed pictures of the past. These, however, are constantly changing as new data come to light.

ancient-life-landscapes/index.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jan-2000