|

Katmai

Building in an Ashen Land: Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 8:

TRAPPING AND OTHER SUBSISTENCE LIFEWAYS

IN MANY PARTS OF ALASKA during the early twentieth century, trapping was an important source of income for thousands of rural residents. The area in and around present-day Katmai National Park and Preserve was similar to much of the rest of Alaska in supporting these activities. From the 1920s through the 1940s, a number of individuals trapped in the rich fur-bearing Katmai country in the winter and worked as salmon fishermen at various Bristol Bay canneries during the summer.

To support their trapping lifestyle, these hardy, self-reliant individuals built cabins, ancillary structures, and traplines near lakes and rivers. Most of this construction took place in the northern and western portions of today's park. A 1931 expansion of the monument boundaries brought the trappers' way of life into conflict with the National Park Service's natural resource protection policies. This action eventually brought an end to the Katmai trappers' lifeway, and little trapping activity has taken place during the past fifty years. Although the time in which they were active was relatively brief, trappers were able to develop almost fifty cabins or cabin complexes within the present park and preserve boundaries. But evidence of their activity has been fleeting, and NPS cultural resources personnel have thus far identified in the field fewer than twenty of those sites.

Historical Trapping Patterns

Trapping and hunting in Katmai region has been traced back to prehistoric times, and during the historic period, trapping doubtless formed an integral part of the subsistence lifestyle of Katmai, Douglas, Savonoski, Kukak, and other area communities. (Some residents of those communities lived elsewhere during the summer; at the Brooks River mouth, for example, some Savonoski residents had long had a fish camp to take advantage of the remarkable salmon run.) Hunting, trapping, and fishing patterns in the Katmai region were dramatically altered by the June 1912 volcanic eruption. All settlements and camps were subsequently abandoned. Most residents no longer used monument resources, but those who were relocated to New Savonoski may have eventually drifted back into the monument and once again carried elements of their subsistence lifestyle. Other local residents, such as those from Naknek, never stopped coming to Katmai in order to participate in long-established traditional activities.

|

| A local resident (either Martin Monsen, Jr. or John Monsen), in this circa 1940 photograph, poses at a cache in the Naknek Lake country. NPS-LACL Photo Collection, courtesy of Dorothy Berggren. |

Most of the early National Geographic Society expeditions to Katmai approached the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes from Shelikof Strait, and in so doing they avoided the prime trapping country west of the Aleutian Range. But in 1919, an expedition visited the newly-designated monument from the west, and on that trip, participants identified two rude trappers' cabins. One belonged to a man named Buckley at "Island Bay" near the portage to Lake Grosvenor, while the other cabin, belonging to "Mr. Grant," was located on the portage between Naknek and Brooks lakes. [1] (Alex Grant may have been the man being referred to; in 1918, Grant discovered gold along American Creek.) The expedition members that year built a log cabin at the head of Naknek Lake to store goods during their trek to the volcanic area. That cabin remained for more than twenty years; more than a decade later, it was used by at least one trapper.

Before long an increasing number of men, primarily local residents, were attracted to the Katmai area's trapping possibilities. As noted in chapter 9, fur prices began to rise during and shortly after World War I, and the Katmai lake country—particularly the country surrounding Naknek and Brooks lakes—promised high trapping yields; as longtime Naknek resident Melvin Monsen noted, "In the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s, fur trapping was a more lucrative activity than was commercial salmon fishing in Bristol Bay waters." [2] By 1925, Stephen M. Scott had relocated to the area just south of Brooks River to commence trapping, and during the next six years four additional men—Verner Eckman, Roy Fure, John Hartzell, and John Monsen—also became actively engaged in the trade. [3] These men, all recently arrived immigrants, built one or more cabins as base camps for their itinerant lifestyle. These men typically trapped only during the seven- to eight-month winter when the pelts (commonly beaver and fox) were in peak condition. They would then return to Naknek. They would sell their furs at the R. Davey General Store, [4] and after the area's canneries reopened, they would spend the summer working as commercial fishermen. (Scott, in fact, was known as "Portland Packer Scotty" because he was affiliated with the Alaska Portland Packers cannery, which operated along the Naknek River from 1919 to 1933. [5])

|

| When Paul Hagelbarger of the 1918 National Geographic Society expedition visited "Tom's Bay" (Lake Brooks), they encountered this barabara and cache. University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Biox 4, 4104. |

In April 1931, a proclamation signed by President Herbert Hoover more than doubled the size of Katmai National Monument. The proclamation stated that the expansion was needed to protect "features of historical and scientific interest and for the protection of the brown bear, moose, and other wild animals." The monument, at that time, had almost no visitation; thus the proclamation had no immediate effect on the monument's megafauna populations. The monument's new boundaries were moved sufficiently far west that each of the five trappers noted above were included. But they and other Naknek residents had scant knowledge of the monument expansion, and conditions continued as before.

High fur prices, and a continuing, active cannery presence, induced other local residents to trap in the Naknek Lake country. In the next five years, at least nine new trappers became established. Those nine included Gunnar Berggren, Paul Chukan, Alfred Cooper, Harry Featherstone, John "Frenchy" Fournier, Sigurd Lundgren, Richard Mitchell, Martin Monsen, and a man named Karvonen. These men were both Natives and non-Natives, and both recent and long-term U.S. residents. Most if not all were Bristol Bay residents who divided their year between the trap lines and the canneries. [6]

Trappers Leave the Monument

|

| Above: John "Frenchy" Fournier was a Katmai-area trapper during the 1930s; he was one of several who left the monument as a result of the Kinsley investigation. Photograph taken in 1923 by Alyce C. Anderson, a Naknek teacher. Alyce Anderson Collection, LACL, courtesy of Theodore W. Anderson. |

The trappers' lifestyle became endangered, however, beginning in 1936. Early that year an Alaska Game Commission (AGC) agent out of Dillingham, Hosee R. Sarber, visited Naknek and was surprised to find that "quite a number of trappers" were operating in the Naknek Lake-Lake Grosvenor country, most of whom were unaware that they were doing so within a national monument. Spurred on by that discovery, the AGC began patrolling the monument's Shelikof Strait coastline and found "several violators operating in and adjacent to the park." Word of the violations eventually found its way to NPS Director Arno Cammerer, but neither he nor anyone else could react to the problem until the Mount McKinley Superintendent agreed to dispatch a ranger to the area. But the visit was just a one-day flyover, and the trapping problem remained. As additional reports of violations continued to pour in, so the NPS asked the General Land Office to look into the matter. In January 1938, investigator A. C. Kinsley undertook the task. He visited Naknek that July and completed his report the following January. Kinsley, giving the trappers the benefit of the doubt, said that all those who had settled into the area prior to the 1931 proclamation had the legal right to continue living in the monument, even though they had never filed for legal rights to the land. But in an ironic twist, they were prohibited from trapping because that activity violated NPS regulations. Those who had entered the monument after the proclamation had no legal basis to either live or trap in the monument. [7]

When Supt. Frank Been and biologist Victor Cahalane visited the monument in the summer of 1940, they were pleased to discover no signs of active trapping; on the contrary, they saw several stripped cabins and abandoned caches. The trappers had apparently moved out of the Bristol Bay side of the monument. But as Cahalane soon discovered, the situation was different along Shelikof Strait. The biologist, along with an AGC agent, spent several days patrolling the coastline. He made no specific mention of active trappers; he did note, however, that it was "perfectly feasible for poachers to base their operations on any one of the numerous [offshore] islands while they may trap on the mainland of the monument with greatly enhanced chances of escaping detection." Cahalane, hoping to separate the legitimate fox farmers from any illegal trappers that might be in the area, suggested that the monument's boundary be extended two miles east into Shelikof Strait. But before the agency finalized its recommendation, it drafted the GLO's A. C. Kinsley to study the situation. Kinsley got the job in April 1941, and before long he discerned that only two men had any legal claims to the offshore islands: Earl Butler, whose Kiukpalik Island fox farm was legitimate (though of marginal economic benefit), and John A. Smith, who had acquired no foxes and otherwise seemed uninterested in fulfilling his fur farm lease. Kinsley, who relied for his information on visits by AGC agents, reported that Smith, under the guise of a fox farmer, was illegally trapping along the Shelikof Strait coastline. As a result of that investigation, Smith lost his fur farm lease in April 1942, and on August 4 of that year, President Franklin Roosevelt added all of the offshore islands to the monument. Those actions eliminated the trapping problem along the monument's eastern shoreline. [8]

|

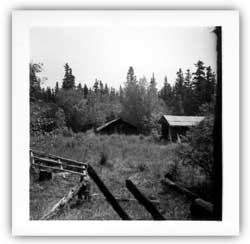

| Believed to be Hammersly cabin complex, 1973. LCS Katmai file, AKSO. |

Meanwhile, officials were beginning to discover that in the country west of the Aleutian Range, the quashing of trapping had been only temporary. With the onset of World War II and the resulting reduction in NPS funding, agency personnel had virtually no opportunity to see the monument for another five years, and in early 1947, a Fish and Wildlife Service agent informed the NPS that four men—one of whom was longtime trapper Stephen M. Scott—were living and trapping inside of the monument. The F&WS agent, with the NPS's blessing, arrested all four of the trappers, who pleaded their innocence based on their lack of knowledge of the monument's boundaries. All were released, but the following year additional trappers—Kirk Adkinson, Henry Nelson, and Jim Marlette—were spotted and arrested. Adkinson, furthermore, was convicted and incarcerated. When an F&WS agent returned in 1949, trapping was as active as in previous years, and he found one cabin that had been extensively used for trapping. But the activity was clearly winding down. NPS officials have noted few problems with illegal trapping since 1950, when they established an on-site management presence at Brooks Camp. [9]

The monument, which was managed on a bare-bones budget until the late 1960s, may well have hosted illegal trapping activity from time to time, although there was little economic incentive to harvest furs during this period. During the 1970s, a resurgence of fur harvest took place throughout Alaska, fueled both by rising prices and a newly-emerging "return to the land" syndrome; historian Melody Grauman notes that the latter condition resulted "from an environmentally conscious society and a recognition of [the] lost values of self-sufficiency and rugged individualism." One person, in pursuit of those values, settled just outside of the monument and spent most of the decade trapping in the American Creek watershed. [10] But when President Carter's 1978 proclamation incorporated huge new areas into the National Park Service system, more than a million acres on the margins of "old" Katmai National Monument were closed to trapping, and the recently-established trapper was obliged to leave. [11] Carter's proclamation and the subsequent passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act meant, quixotically, that trapping would be prohibited in both the old (pre-1978) and new portions of Katmai National Park; the activity could continue, however, in the newly-designated Katmai National Preserve. Since 1950, few if any illegal trappers have operated in the park; thus trapping has had few significant impacts on park resources.

As the above discussion has suggested, trapping activity took place in many parts of the present-day park and was prevalent for many years, particularly between 1925 and 1940. Perhaps the best known of these is Fure's Cabin complex, built by Roy Fure in 1926, which in 1985 was entered onto the National Register of Historic Places. In recognition of its historic value, the NPS restored the cabin in 1987-88 and the remainder of the complex in 1993-94. [12] Almost all of the remaining cabins, however, have severely deteriorated, and the site of many former trapping cabins has not yet been relocated. Because trapping was centered on three geographical loci, the various trapping sites will be discussed in that context.

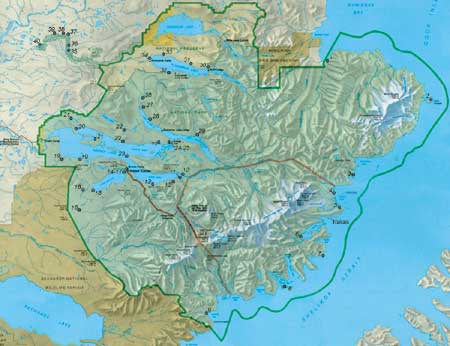

List of Trapping Cabins

|

Shelikof Strait Coastline: 1) Kamishak River Cabin2) Cape Douglas Cabin 3) Chiniak Lagoon Cabin 4) Hallo Bay Cabin #1 5) Hallo Bay Cabin #2 6) Kukak Bay Cabin 7) Kuliak Bay Fish Camp 8) Takli Island Trapping Complex 9) Kashvik Bay Cabins |

Naknek River Basin: 10) Monsen Cabin Complex11) Featherstone Cabins 12) Griggs-Mitchell Cabin 13) Chukan's Research Bay Cabin 14) Scott-Furnier Cabin Complex 15) Grant Cabin 16) Melgenak Cabin Complex 17) Angasan Cabin 18) Osberg-Lundgren Cabins 19) Chukan's Naknek Lake Cabins 20) Monsen/Shapsnikoff Cabin Complex 21) Berggren Cabins 22) Eckman Cabins 23) Monsen Line Cabin 24) Fure's Bay of Islands Complex 25) Buckley Cabin 26) Hartzell's Lake Coville Cabin 27) Fure Line Cabin 28) Hartzell-Fure Cabin Complex 29) Lake Grosvenor Cabin |

Alagnak River Basin: 30) Marlette Cabin31) Neilsen Cabin 32) Murray Cabin 33) Agate Point Tent-Cabin Complex 34) Hammersly Cabin Complex 35) Peterson Cabin 36) Guide Camp Cabin 37) Apokedak Cabin Complex 38) Estrada Cabin Complex 39) Andrew Cabin Complex 40) Lower Alagnak River Cabin Complex |

|

| Map of Trapping Cabins. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Trapping Along the Shelikof Strait

Coastline

1) Kamishak River Cabin: At or near the mouth of the Kamishak River is a cabin site. Evidence of the site was published in a July 1929 newspaper article, which mentioned that two brothers from the Iliamna country, Walter and Ole Wassenkari, would "throw out trap lines" in the vicinity of Kamishak Bay that winter. Ole Wassenkari, the article noted, would live "in the cabin at the Big Kamashak [i.e., Kamishak] River." In his later years, Mr. Wassenkari (1899-1984) lived along Ole Creek (a tributary of the Kvichak River) just west of Iliamna Lake; he worked as both a "Bristol Bay fisherman and a Kvichak-Iliamna trapper." [13] The cabin was probably used for trapping for a short time, if at all. The specific location of the cabin is not known, and nothing is known of the cabin's condition. As has been noted in Chapter 6, there was a flurry of oil-lease activity along Kamishak Bay and the Kamishak River in the early 1920s; the cabin may have been built as a result of that activity.

2) Cape Douglas Cabin: On the northwest side of the Cape Douglas headland is located the ruins of a sod and plank cabin. Nearby is a storage cache or shed, built of upright wooden planks, along with a possible second cache. The house ruin consists of a 4 x 5-meter rectangle of low sod walls banked against vertical planks, with stumps of upright posts. Loose, horizontal planks from the roof or walls of the house are scattered across the foundation and outside. The boards contain drawn wire nails. A small cast iron stove with a square flue sits inside the house. The complex dates from the 1940s or 1950s; who built the structures, or why, is unknown. Archeologists discovered the site in 1994; it is now registered as AHRS Site No. AFG-199. [14]

3) Chiniak Lagoon Cabin: George Stroud and Lynn Fuller, in their 1984 report, noted that one map of the area showed "a cabin on the peninsula one mile northwest of Cape Chiniak." The two did not visit the cabin, however, and no other records about the cabin are known to exist. Should remains of the cabin still exist, they are probably located near the end of the spit north of the lagoon mouth. Who built the cabin, or why, is unknown. [15]

4) Hallo Bay Cabin #1: A cabin was built along the western shoreline of Hallo Bay, approximately 1-1/4 miles south of where the Ninagiak River debouches into the bay. Who built the cabin, or why, is unknown. In June 1976, park interpreter Carolyn Elder visited and photographed the cabin, which was located in an alder patch. She also learned during an interview in Kodiak that "a gentleman by the name of Gene Weaver" had the cabin; his probable residence was a community on Kodiak Island. The cabin photo is located in the park collection. [16]

5) Hallo Bay Cabin #2: A cabin was built on the south side of Hallo Bay. The location of the "old cabin" has been variously described as being "1/2 mile from beach" and simply "south side Hallo Bay." These two photo captions probably describe the same cabin; if so, its probable location is on a small rise just south of a large pond in T20S, R29W, Section 34, SE1/4. Who built the cabin, or why, is unknown. Park interpreter Carolyn Elder, in 1976, learned that Gene Weaver had both this and the other Hallo Bay cabin. In May 1978, ranger Rollie Ostermick visited and photographed the cabin. Two cabin photos with that date are located in the park collection. [17]

6) Kukak Bay Cabin: As part of a series of tape recordings she made during the mid-1970s, Carolyn Elder learned that Jake Amuknuk had a cabin at the head of the bay. Mike Tollefson's 1977 report notes that the man hailed from Kodiak. [18] No information is available about the cabin's location, history, or condition.

7) Kuliak Bay Fish Camp: As part of his operation, John A. Smith (see below) had a fish camp just north of Kuliak Bay, at the head of the peninsula just south of Cape Gull. It was probably active in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Smith probably never constructed more than a tent and a series of fish racks at this site. [19]

8) Takli Island Trapping Complex: As noted in chapter 9, federal authorities administered this site (AHRS site number XMK-073) as a fox farm. In actuality, however, the only known site occupant used the complex as an illegal trapping headquarters. Fur farm leases were taken out for the island in December 1928 and July 1931, but neither act was followed up by on-site settlement. Then, in 1937, John A. Smith applied for a fur farm lease. Smith soon built a cabin and two caches on the island's northeastern quadrant, and in 1939 his lease was approved. But instead of establishing a fur farm, he illegally hunted mink, marten, beaver, and fox within Katmai National Monument. As a result, he lost his lease in May 1942. Eleven years later, an NPS aerial photo showed a large cabin, a smaller cabin or shed, and a shed built into the hillside; all were probably erected by Smith during his five-year tenure on the island. These structures deteriorated over the years; they were still standing during the early 1970s, but by 1991 all had collapsed. It is recommended that NPS cultural resource personnel conduct a survey of the site's historical archeology. [20]

9) Kashvik Bay Cabins: In 1917, a National Geographic Society group stopped at Kashvik Bay as part of a Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes expedition. Photographs taken from that trip show two cabins in the bay: a "prospector sod house" and a "cabin on Moose Creek." The locations for both structures are indefinite, inasmuch as the sod house was not further identified and the name Moose Creek is not an official name for any watercourses in the bay's drainage. The only suggestion regarding who built them is found in Mike Tollefson's 1977 letter in which he noted that "Freddie Grindell's father" had cabins at Kashvik and other bays along the Shelikof Strait coastline; he trapped foxes in the vicinity of those bays (according to his son) in the 1920s and 1930s. [21] Perhaps the Moose Creek cabin was used for trapping, while the "prospector sod house" was used in conjunction with the Mason brothers' gold extraction activities along Lonesome Pine Creek, near Cape Kubugakli. (See Chapter 6.)

|

| This photo of Johnny Monsen's Reindeer Point (Northwest Arm) cabin was taken about 1940. NPS-LACL Photo Collection, courtesy of Dorothy Berggren. |

Trapping in the Naknek River

Drainage

10) Monsen Cabin Complex: John M. Monsen, a part-Native resident locally known as "Johnny," was born about 1904. He moved into the Katmai country to trap in either 1926 or 1930 and reportedly hunted and explored the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes with Harry Featherstone during this period. Who built his longtime cabin at the east end of Iliuk Arm is uncertain; once source says that John "Frenchy" Furnier built it and lived there before Monsen moved in, while another source says that he, his brother Martin, and Alfred Cooper built it. [22] Throughout the 1930s he resided at his cabin for seven months (August through March) each year. Over the years, he built a complex that included a cabin, fish house, storeroom, and bathhouse.

There is some dispute, however, about both the location and other specifics of Monsen's cabin complex. A. C. Kinsley, the Interior Department investigator, wrote that his four-structure cabin complex (as specified above) was located at the south bank of the mouth of the Savonoski River and that his cabin was 14' x 20'. (Kinsley did not include Featherstone or his cabin in his report. He erroneously states that John Monsen and Martin Monsen were alternate names for the same person; Martin Sr., in fact, was John's father, and Martin Jr. was his brother. [23]) But Frank Been, who visited the site in September 1940, clearly mentioned that Monsen's headquarters was on the north side of Iliuk Arm, approximately 1-1/2 miles northwest of the Savonoski River mouth. He further stated that the cabin's dimensions were 10' x 30'—clearly different from what Kinsley had written. Been noted that Monsen's cabin was constructed of logs and had a tin roof; it was in good condition and showed active usage, although the tenant was absent. Been noted that Monsen's complex had four (not three) outbuildings and caches, all of which were in fair shape. A short distance from the cabin were salmon drying racks, Been observed.

Perhaps the discrepancy in the description of the two camps can be addressed by evaluating the authenticity of the two source materials. Kinsley, unlike Been, did not visit the site but relied on others for his information, and Been had the further advantage of being shown the site by a local (and presumably knowledgeable) fisheries agent. One plausible scenario, therefore, is that the camp that Kinsley described as being Monsen's was, in fact, Featherstone's. This scenario, including Kinsley's description of "Monsen" having a remote line cabin, is consistent with other information that has been compiled about Featherstone.

Monsen, a dedicated trapper, was slow to leave the monument. Although he clearly knew that trapping was illegal, he appears to have remained at his cabin until March 1940, when Alaska Game Commission warden Carlos Carson arrested him. (His brother, Martin Monsen, Jr., and fellow trapper Alfred Cooper were arrested at the same time.) [24] When Been arrived in early September 1940, he noted that the cabin "showed active usage although the tenant was absent." But when he returned two weeks later, he discovered to his surprise that "the cabin and premises had been stripped of everything of value." Been, conversing with his pilot about the matter, mentioned that Carson, when he arrested him six months earlier, had ordered Monsen to "give up his cabin" but that other priorities had intervened in the meantime. Been noted that Monsen had stripped the cabin on or about September 15th. [25]

After leaving his cabin, Monsen joined Mike Shapsnikoff at his cabin on the upper King Salmon Creek for awhile. [26] But by 1950, he was living in Naknek, lobbying to have the monument opened to trapping. He may, for a time, have trapped out of a cabin at the mouth of Headwaters Creek, at the southwestern end of Lake Brooks (see Ostberg-Lundren Cabin). Monsen died in 1955. [27]

What became of the cabin is uncertain. Government biologist Victor Cahalane has said that Monsen "partly wrecked" his cabin shortly after abandoning it. [28] Naknek resident Elmer Harrop, testifying in 1983, stated that "Johnny Monsen had a cabin toward the head of Naknek Lake which was destroyed" and implied that personnel from either Northern Consolidated Airlines or the NPS were responsible. But the cabin was apparently still standing as late as the 1970s, because NPS personnel during this period located it and removed a number of Monsen's books to the monument museum. [29] The cabin's present condition is unknown.

11) Featherstone Cabins: Nothing is known of Harry Featherstone prior to 1926, but it may be surmised that had become familiar with the Katmai country and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes by that date. Early that year (if his residency application is to be believed) he began building a cabin along the north side of Naknek Lake's Iliuk Arm. In May of that year, he and Roy Fure guided schoolteacher Alyce E. Anderson from Naknek to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and back; along the way, the party stopped at Featherstone's completed cabin, which Anderson photographed. He apparently continued to trap in the area for another decade, expanding his operations during that time.

|

| Both Harry Featherstone (left) and Roy Fure trapped in the monument during the 1930s. Photograph taken in 1923 by Alyce E. Anderson, a Naknek teacher. Alyce C. Anderson, Collection, LACL, courtesy of Theodore W. Anderson. |

In 1936, Alaska Game Commission agent Homer Jewell noted that of the trappers who were operating inside of the newly-expanded monument, "Weatherspoon" [i.e., Featherstone] was "the most aggressive. Our information shows that [he] has several trapping cabins at or near the head of the Naknek Lakes located just outside the old [1918] boundary lines of the Park." Featherstone was known to officials for two other actions as well. First, he had decorated his cabin with 35 carved wooden masks that he had removed from beneath a sheltered overhanging cliff near Old Savonoski. Second, it was reported that he had constructed a platform near the mouth of a salmon spawning stream on Naknek Lake from which he would shoot brown bears; he sold the bear hides to Bristol Bay fishermen to cover themselves while resting on their fishing boats.

Featherstone apparently abandoned his cabin shortly 1936, because he is not mentioned in the 1938-39 Kinsley investigation. Unfortunately, a specific location was not described for any of Featherstone's cabins; Jewell merely noted (as shown above) that his various cabins were located "at or near the head of the Naknek Lakes," and none were identified on contemporary maps. The better-known Monsen cabin is located in the same general area, but inasmuch as both were simultaneously active, and because they were not known to be partners, it is highly doubtful that the two men occupied the same cabin. (Note: see "John Monsen Cabin Complex" above for further clarification.) The location of all of Featherstone's cabins is unknown today; the conditions of those cabins are thus unknown, though they are in all probability in a collapsed condition. [30]

12) Griggs-Mitchell Cabin: In 1919, Robert Griggs led his fourth National Geographic Society expedition to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Most of the group accessed the valley by way of Shelikof Strait and Katmai Pass, but four expedition members arrived at the east end of Iliuk Arm by circling around the Alaska Peninsula and ascending Naknek River. As part of that trip, the expedition established a base camp near the mouth of the Ukak River. As numerous photos taken that year show, it was primarily a tent camp, but expedition members also constructed one cabin. [31] Its dimensions, according to varying sources, were either 13' x 16' or 14' x 16'. Frank Been, who visited the site in September 1940, called it "a tight cabin of spruce logs." He wrote that "it was nicely situated in shelter of high sand dune and close to lake shore. Its size and condition make it practical for reconditioning and it will serve excellently as a base camp. It is quite a fortunate facility." He did not indicate whether the cabin was east or west of the Ukak River mouth, but inasmuch as a trail led from the cabin to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, it was probably located just west of the river mouth. An NGS map drawn from the 1916-19 expeditions suggests that this "hut" was located approximately 1-1/2 miles west of the river mouth.

The cabin was probably unused between 1919 and 1935. That October, 30-year-old Richard Mitchell moved into the cabin in order to trap. He remained there for only three months, however, and did not return. By 1939, Mitchell was living in Snag Point, near Dillingham.

The cabin was a popular destination of later explorers. Victor Cahalane, who accompanied Been in 1940, told Been that the cabin was "close to the beach" and "in a good state of preservation." J. C. Roehm, who visited the following year, indicated that the cabin was uninhabited; the trail between cabin and the upper Ukak River valley was grown up and "cannot be followed with any great degree of success." Grant Pearson, a 1945 visitor, injected a worrisome note when he wrote, "Near the mouth of the Ukak River we located a log cabin with a tin roof, but as the river had cut in the timber and streams were flowing on both sides, it looked as if the cabin might be washed out by the river." In 1954, geologist G. Donald Eberlein made an area reconnaissance; his description of the cabin, however, suggests that he did not make a site visit. [32]

So far as is known, no one in recent years has visited the cabin. Its exact location is not known, and its condition cannot be evaluated.

|

| Paul Chukan, who trapped for years inside of the present-day park, is shown here on a fishing boat off Naknek Point. NPS-LACL Photo Collection, courtesy of Katherine Brown. |

13) Chukan's Research Bay Cabin: Paul Chukan, a Native American, was born in Naknek on July 5, 1901. In 1933, Chukan used a cabin located on the west side of Research Bay, at a stream mouth; it is not known if he built the cabin. In a questionnaire he filled out in the late 1930s, Chukan noted that he used the cabin only once, but others apparently used it as well because Frank Been, during his 1940 visit, noted that the cabin

"showed evidence of recent use but it did not appear to be used as a year round habitation. Perhaps the occupant was a trapper, hunter, or fisherman." NPS personnel during the 1970s were able to locate the cabin and take photographs of it. Its condition in recent years is unknown. [33]

14) Scott's Cabin Complex: Stephen M. Scott was born in Australia about 1883. It is not known when he arrived either in the United States or in the Naknek area, but it is probable that during the early half of the 1920s he became affiliated with the Alaska Portland Packers cannery, which operated along the Naknek River. (He soon earned the nickname "Portland Packer Scotty.") Then, in August 1925, Scott moved into the lake country and settled down midway between Naknek and Brooks lakes, just south of Brooks River. Before long he had erected an 11-1/2' x 13' cabin and two caches: one 8' x 10', the other 6' x 8'. Based on those improvements he recorded a claim to the site in either 1929 or 1930.

In 1936, Scott—still an alien—learned that his trapping operations were illegal because of the westward extension of the monument boundaries. He responded by firing off a letter to Alaska's Congressional Delegate, Anthony Dimond; he demanded that he and other trappers had the right to continue using the monument, and he asked for help in getting compensation if the monument's trappers had to be evicted. Compensation was warranted, Scott pointed out, because "I leave a full year's supply of provisions ahead every year equipment costs quite a large sum to get in there and [an even] larger expense to move back to salt water." Dimond, however, was unable to help. Kinsley's investigation, which began two years later, determined that Scott (and other pre-1931 trappers) had the legal right to live in the monument, but they were prohibited from trapping because NPS regulations forbade it.

By 1939, therefore, Scott was well aware that his activities were illegal. Scott, however, responded by acquiring a partner: longtime area resident (and fellow non-citizen) John "Frenchy" Furnier. Perhaps in response to that partner, several additional feet were added on to the cabin.

|

| Above: Scott's cabin complex as it appeared in 1962. The cabin is in the center of photo. NPS-LAKA Studies Center Collection. |

In mid-May 1940, Alaska Game Commission agent Carlos Carson visited the cabin, apprehended the pair, and told them that it was time to abandon their operation. Carson noted that the two men received the news differently: "Furnier wanted to release the skins [and told] Scott that he knew sooner or later they would get into trouble in the park. But Scott is an old offender and would not hear of it." Carson confiscated a total of 61 skins, which included lynx, wolverine, mink, otter, fox, and beaver; he also confiscated 42 fresh pairs of beaver castors. (Castors come from a beaver's perineal glands and are used in perfumes and perhaps for other purposes as well.) Scott and Furnier left, though grudgingly; they did not, however, take their equipment and personal belongings with them.

Frank Been, in September 1940, gave an extensive description of the site: "We came upon a cabin with 2 caches, dog houses, and some odds and ends of paraphernalia. The cabin was about 12 x 18 feet and 10 feet high at the gable sloping to less than a man's height at the eaves. Although apparently originally built of logs, the structure was covered with flattened 5-gallon gas cans in front, and with earth thrown high against the sides. Roof was galvanized corrugated iron. One cache contained equipment such as snow shoes, moccasins, etc. The other appeared little used. In the enclosed porch of the cabin were scores of steel traps. I was told by one of the boys attending the salmon counting weir at Brooks Lake that Scott had said he was not going to live in the cabin this winter. Apparently Wildlife Agent Carson's activity this spring has discouraged Scott from making an illegal living in the monument."

Scott was not gone from the area for long. By 1945, he was considered "the only poacher in the area," although he was gone when an NPS official dropped by. Two years later, however, Carson once again caught him living and trapping in the monument, and he was quickly arrested and hauled off to Naknek for a commissioner's hearing. He still, however, felt that he was being wronged, and he fired off another letter to Dimond (who was now a Federal court judge) complaining that he had been denied a trapping license because of his alien status. Scott finally left the cabin for good; he died during the 1950s.

|

| Scott's Cabin as it appeared in 1998. NPS-KATM HRS Collection. |

George Eicher, who as part of the Fish and Wildlife crew was a frequent visitor from 1940 through the mid-1950s, noted that "Scotty and Frenchy had a very elaborate layout at the outlet of Brooks Lake. It was an unusually lavish layout for trappers. They had a big cabin which really was quite nice. They had kennels for the dogs in a long line made of poles and logs so that each dog had an individual kennel to go into. They also had several outbuildings for various purposes, out sheds for putting fish in and all those sorts of things.... When we went in there first, in 1940, it looked like they had just left.... They had a large collection of National Geographic magazines and intellectual books such as a complete library of 'Bulwer's Works' by Lord Bulwer-Lytton. We perused most of these in our spare time. Strangely, [the two men] went away leaving virtually all of their possessions, including stocks of canned food. It may have been that they received eviction notices while away and simply did not return." [34]

During the 1940s, the cabin complex was located along the old road that connected the Lake Brooks field laboratory with the Brooks River fish ladder. [35] Later, however, that road was abandoned, and in recent years the site has become surrounded by the encroaching forest. In 1975, Robert Carper of the NPS visited the site; he noted two cabins (one 12-1/2' x 20', the other 8' x 10') and added it to the agency's List of Classified Structures inventory; information for the LCS file was updated after a 1993 visit. In June 1999, the NPS completed a Determination of Eligibility form for the property (AHRS Form No. XMK-123) and urged that it be considered eligible to the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A; a month later, Alaska's State Historic Preservation Office concurred with that finding.

|

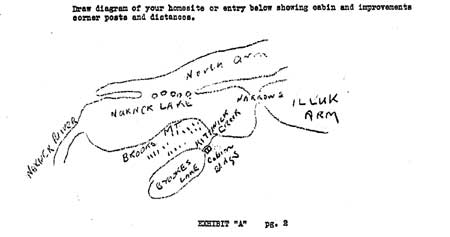

| Above: Trapper Stephen Scott drew this map of his cabin complex and the surrounding area in the late 1930s in hopes of legalizing his claim. KATM files, NARA DC. |

15) Grant Cabin: By 1919, a man named Grant had built a cabin near Brooks River. National Geographic Society expedition members that year mentioned that he was "a character" and that his nickname was "Old Man Grant;" he was probably Alex Grant, an area prospector who in 1918 had discovered gold along American Creek. The NGS team took three photographs of the cabin, which was "located on the portage between Naknek and Brooks Lakes." Unfortunately, no other information is available, either about its specific location or its use patterns. The photos suggest that the cabin was a little more than an A-shaped framework of parallel logs, perhaps five feet high at the apex, covered with dirt. It is unlikely that either Stephen Scott, the Melgenak family, or the Angasan family used this cabin during their residence in the area. [36]

16) Melgenak Cabin Complex: Various sources refer to either one, two, or even three cabins clustered in the small area between the Brooks River mouth and the Beaver Pond. Most of the available information pertains to the Melgenak Cabin, but all cabins in this area will be discussed in this section.

According to Trefon Angasan, Sr., who testified about the area's cabins in September 1985, "American Pete" had constructed a cabin near the mouth of Brooks River during the early twentieth century. He and his wife, Palakia, stayed in that cabin. "American Pete" died in 1918, and a year later she married Nick Melgenak, the new chief at New Savonoski, who was commonly known as "One Arm Nick." At some point the cabin caved in, so Mr. Melgenak rebuilt it. There is some controversy regarding the age of that cabin, however; Mike McCarlo testified that Nick rebuilt that cabin before 1925, but an NPS ecologist, using tree-ring dating techniques, stated that the cabin was constructed "sometime after August 1931." Another cabin was constructed in the area somewhat later; according to the tree-ring expert, this second cabin was built "no earlier than the summer of 1936." [ 37] Mike Tollefson, who interviewed Mike Shapsnikoff in the mid-1970s, reiterated that "One Arm Nick's cabin was located in the grove of trees near the tern spit on the south side of Brooks River," but he also noted that "Frenchy [Fournier] may also have lived in one of these cabins from time to time."

Frank Been visited a "fishing village at Naknek Lake near the outlet of Brooks Creek" in early September 1940. Been further noted that "the place is hardly a village because it consists of two cabins. When the Aleuts arrive to fish, they pitch tents. One-Arm Nick occupied the desirable cabin which was quite comfortable." The only other improvements he noted were "a number of fish drying racks" that were "scattered along the stream bank." [38]

The use of the cabin apparently stopped shortly after Been's visit. George Eicher, who visited the area between 1940 and 1956, noted that the Natives "had temporary camps and drying racks at the river mouth," and Mike Shapsnikoff, who moved to the area from Dutch Harbor in 1936, indicated to NPS officials "that the cabins in the woods near the ponds were down when he 'came into the country.'" Mike Tollefson noted three collapsed cabins in this area in his 1977 report, but NPS investigators in 1984 located only two structures, both of which were in ruins. [39] Unlike several other cabins in the monument, no evidence has been suggested that any of these cabins were razed by either NPS or Northern Consolidated Airlines officials.

17) Angasan Cabin: Trefon Angasan, Sr. was a longtime user of the fish camp at the mouth of Brooks River. According to Angasan's testimony as well as that of several other observers, he constructed a cabin on the north side of Brooks River sometime between 1925 and 1950; during this period, he and his family stayed there when putting up fish. Neither the date of construction nor the cabin's location, however, is known, and no architectural details are available. (The cabin was probably not built before 1925 because Mike McCarlo, in 1985, testified that during the early to mid-1920s Angasan stayed in One Arm Nick's cabin south of the river.) [40]

There is conflicting evidence that this cabin, which was at or near the site of the NCA complex at Brooks Camp, was sacrificed as part of the concessioner's expanding camp operations. Ray Petersen, who founded the camps in 1950 and helped manage them until the late 1960s, averred that an old cabin existed at the site but that his company never tore it down. In May 1983, Petersen testified that "There was one cabin, apparently an abandoned trapper's or poacher's cabin, which contained two bunks and was occupied occasionally by employees of our camp. No other structure or evidence of one existed on north side of river. No buildings or structures have been removed or destroyed by our operation on the north side of the Brooks River to my knowledge." Furthermore, he noted that no Brooks Camp structure had been built where the trapper's (or poacher's) building had been located. [41]

Others, however, disagree with Petersen's assessment. Trefon Angasan himself, who testified just three weeks later as part of the same case, stated that "My cabin was there until NCA bulldozed it," and Elmer Harrop similarly testified that "Trefon Angasan's cabin on Naknek Lake was destroyed." Darrell Coe, who served as Katmai National Monument's Management Assistant during the summer of 1966, tersely noted in his report for June of that year that "One abandoned cabin razed near mouth of Brooks River." Because no other "abandoned cabins" were known to exist north of the river (and there is little reason why a cabin south of the river would be considered), it appears likely that either the NPS or the NCA demolished the Angasan cabin in 1966. [42]

18) Osberg-Lundgren Cabins: This cabin is located on a small bluff just south of where Headwaters Creek debouches into Lake Brooks. Rongald Osberg built the 14' x 15' cabin in 1930, and he recorded a claim for the site in 1931. He continued living at the cabin, on a seasonal basis, and as part of his trapping operations he built three 10' x 12' line cabins. Osberg died in 1934.

Some sources note that Axil Erling, a 39-year-old local resident, occupied the cabin shortly after Osberg's death; Erling lived there only a short time before Sigurd Lundgren occupied the site, and he never claimed the property. [43] Other sources state that Lundgren, in 1934, purchased the four cabins from Osberg's administrators (and omitted any mention of Erling). Lundgren, who had arrived in the U.S. just the year before, trapped out of the cabin until 1938, when investigator A. C. Kinsley evaluated his claim. Kinsley's report, published in 1939, concluded that he had no valid rights to either live or trap in the monument. Lundgren apparently added on to the cabin during this period.

|

| Trapper Sig Lundgren is seen with 42 foxes and two otters that he and Gunnar Berggren harvested. This 1939 photo was taken in Naknek. NPS-LACL Photo Collection, courtesy of Dorothy Berggren. |

Frank Been visited the cabin in early September 1940 and discovered it to be "in good condition and showed active use. Its dimensions were 12' x 24'. Corrugated tin covered the roof. Close-by was a cache made of logs. In it were miscellaneous articles of winter apparel and equipment and several steel traps and a beaver pelt. Five roughly constructed dog houses were scattered about the premises. The site was nicely located on a high bank over the streams and close to the lake but protected from high winds by a screen of trees. On the opposite shore of the stream was a crumbled cabin and cache which we assumed had been used by Lundgren before he built the present abode. Lundgren has another cabin about 15 miles up the stream and well outside the park." Been, upon returning to Naknek, hoped to talk to him so as to coax him to leave his cabin; he met him but was unable to talk to him about his activities in the monument. Been found that he had "quite an aggressive manner." Lundgren took the meeting as an opportunity to lobby the NPS official about opening up the local area (outside the monument) to moose hunting "so that this source for fresh meat will be available." [44]

Lundgren apparently took Been's cue and left the monument, but the cabin was later used by several other trappers. Shortly after World War II, Kirk Adkinson (a 32-year-old fisherman) and Henry Nelson decided to trap in Lundgren's old territory. Protection officer Carlos Carson, upon hearing rumors of that activity, warned them to stay out of the monument, but during an overflight in early March 1948 he "noted much activity. Investigation showed the cabin full of all trapping equipment, grub, 2 beds, stove, stretchers, etc. etc. Fresh tracks in the snow revealed one occupant had recently left; following this track for 150 yards a fox, recently killed was in a trap on the bank of the river. A short distance farther on were several sets right by a beaver house. Although we tracked him for several miles, we returned to the plane owing to the time of day, but left note in cabin, telling them what we took and for them - or him, to remain until we called for them."

Of the two men who were involved in the operation, Henry Nelson stated he had not used the cabin but was using the cabin six miles up the creek. (This was probably one of the line cabins that Osberg had built in the early 1930s.) Adkinson, in Carson's words, "took all the blame, pled guilty, said he knew he should not have done it." The commissioner in Dillingham tried them later that month and gave Adkinson 30 days in jail with five months suspended. Nelson was not penalized. Adkinson apparently heeded Carson's admonitions and left the monument, and so far as is known, the cabin was never used for trapping again.

The cabin thereafter deteriorated fairly quickly. In March 1949, Carson described the cabin in "fair condition;" that assessment was reflected in a photograph that Victor Cahalane took of the cabin in 1953. By 1977, ranger Mike Tollefson (somewhat overstating the case) claimed that "to the best of my knowledge, nothing remains of it today." In June 1986, NPS employee Christopher Ryan made a site visit and noted that the only reminders of the old cabin were ten or twelve logs, "most of [which] were being covered over by mosses."

In order to accurately evaluate trapping in this portion of Katmai, an investigation should be made of a total of five sites. These include the cabin noted above, an earlier cabin that was constructed on the opposite site of Headwaters Creek, and Osberg's three line cabins. Two of these cabins have been geographically identified in the existing literature; one (noted in the late 1930s) was located "fifteen miles up the stream," while another cabin (noted in the late 1940s) was "six miles up the creek." Both of these cabins, of which no other information is known, were located outside of the monument boundaries as established in 1931; they therefore may have been legally used until Congress expanded the monument's boundaries yet again in December 1978.

|

| The Paul Chukan cabin complex, located near the southwestern end of Naknek Lake, included this dilapidated sauna. The photo was taken in 1993. LCS Katmai file, AKSO. |

19) Chukan's Naknek Lake Cabins: Paul Chukan, a Native who was born in 1901, spent some time at a cabin on the Research Bay shoreline in 1933 (see "Chukan Research Bay Cabin," above) and also was a frequent visitor to the Brooks River mouth to harvest salmon. Sometime during the 1930s or 1940s (according to the List of Classified Structures report), he constructed a small cabin near the southwestern end of Naknek Lake. The cabin was constructed of plywood on logs, with a tin roof; adjacent to the cabin are a sauna, outhouse, sawbuck, and similar materials. The complex is located a few hundred feet from a small creek; the site is approximately one mile south of Naknek Lake and is located in T18S, R43W, Sec. 25, NW.

The cabin, which Alex Alvarez probably also used, was apparently abandoned long ago. When visited and photographed in 1993, the entire complex was in ruined condition. The cabin is still standing, though portions of both the roof and walls are missing. (See the LCS file for AHRS Site No. NAK-066.) These improvements appear to be located on the Native allotment of Anna Chukan; Paul Chukan applied for a Native allotment elsewhere in Katmai National Park. According to Mike Tollefson's report, Paul Chukan is reputed to have a "small cabin or tent frame" along Naknek Lake that he used for trapping. The map that accompanies his report suggests that it is near the Naknek Lake shoreline, perhaps five or six miles east of the cabin complex described above. The site of this cabin, however, has not been verified in the field. [45]

20) Shapsnikoff Cabin Complex: Mike Shapsnikoff moved into the Naknek area from Dutch Harbor in 1936, and he built a cabin on the northeast side of Northwest Arm (at the northwest end of Naknek Lake) in 1948 or 1949. (He and his partner, Johnny Monsen, lived in a nearby tent frame "several miles up from the beach.") The two spent the next several winters (September through April) using the cabin as a trapping headquarters. After Monsen died in 1955, Shapsnikoff apparently began to assume control over Monsen's cabin on upper King Salmon Creek (outside of the present park), but continued to spend considerable time at the Northwest Arm cabin. In 1969, his cabin became part of Katmai National Monument when the boundaries were extended west to include all of Naknek Lake. He continued to use the monument for subsistence purposes off and on up through 1974, although it is not known whether the Northwest Arm was his base of operations throughout that period.

|

| Mike Shapsnikoff's cabin complex included a cabin, outbuilding and cache. Mike Tollefson, an NPS ranger, took this photograph in July 1975. NPS-LAKA Studies Center Collection. |

The cabin complex consisted of a cabin, perhaps 10' x 25' in size, and a series of six dog houses. Tollefson and Shapsnikoff visited the site in July 1975; at that time, both the cabin and the dog houses were still standing. Tollefson photographed the cabin as part of that visit. [46]

NPS personnel have visited this site in recent years, but so far as is known, cultural resource personnel have not been there or evaluated its condition.

21) Berggren Cabins: Gunnar Berggren was born in Drammen, Norway, in November 1898. He came to the United States in 1927 and established residency in the United States in 1933, in Anchorage. [47] Three years later, he moved into the Katmai country and built a 12' x 14' cabin on the west side of the Naknek Peninsula, just south of the isthmus. According to Interior Department investigators, Berggren thought that his cabin was outside of the monument. But a Fish and Wildlife agent charged him with trapping in the monument and confiscated all his furs. He therefore moved west and built a 10' x 12' cabin on the south side of Pike Lake (which is two miles north of Northwest Arm). Kinsley, in his 1938 investigation, declared that Berggren did not have the right to either live in or trap from his first (Naknek Peninsula) cabin, but because he had apparently vacated that cabin a year earlier, Kinsley's verdict had no effect on Berggren's lifestyle. If letters he wrote to Delegate E. L. Bartlett are any indication, he apparently remained a seasonal resident at his Pike Lake cabin until the early 1950s. (He spent his summers in Naknek.) As late as January 1969, he apparently still kept an interest in his Pike Lake cabin, because he protested the boundary expansion that absorbed his property into Katmai National Monument. [48] Berggren died in Naknek on January 9, 1981.

|

| Paul "Paddy" Monsen (left) and trapper Gunnar Berggren are shown at Berggren's cabin near Naknek Lake in photo taken about 1940. NPS-LACL Photo Collection, courtesy of Dorothy Berggren. |

Unfortunately, no information is available about either the exact location or the condition of Berggren's cabins. Ray Petersen recalls having seen the Naknek Peninsula cabin on flights between the various NCA camps during the 1950s, but neither Mike Tollefson nor any other NPS personnel have recorded a site visit. Several photographs of the Pike Lake cabin have been recently published in John Branson's volume, Bristol Bay, Alaska, but so far as is known, NPS personnel have not visited the cabin site.

22) Eckman Cabins: Verner Eckman was born in Finland in 1886. He moved to Alaska in 1921, and before long he moved to the Naknek area, where he worked for many years as a commercial fisherman. In 1930 he began to work as a trapper along the north shore of Naknek Lake. He was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1936.

By 1938, Eckman had constructed four cabins in the area. None of these cabins have been located in recent years, however, and available sources have provided different descriptions of their location. A map that Berggren provided to Kinsley during the 1938 investigation suggests that his main (largest) cabin was at the mouth of the unnamed creek that drains Idavain Creek, and Mike Tollefson's report states that "his cabin is located on a ridge near the peninsula 5 miles east of the Naknek Peninsula." Most likely, however, the main cabin—plus an adjacent smaller cabin—are located approximately ten miles east of the Naknek Peninsula isthmus, where the 1:250,000 Mount Katmai USGS map indicates two "ruins." (The 1:63,360 map shows three ruins at the site.) These ruins are located in T17S, R40W, Sec. 25, SW. According to the description he gave Kinsley, Eckman had both a 13' x 16' cabin and a 10' x 14' cabin at this site; the third structure, therefore, may be an outbuilding.

According to Kinsley investigation data, Eckman had two other cabins. One was a 10' x 12' cabin east of his main camp and near the northeastern corner of North Arm; the other is another 10' x 12' cabin due north of his main camp. Both were probable line cabins for his trapping operation. More specific locations for both of these cabins are not available.

Eckman apparently continued to trap in this area until the spring of 1940, when Carlos Carson arrested both Eckman and a man named Karvonen for trapping inside of the monument's boundaries. He apparently left the area soon afterward and did not return. By the 1950s he was living in the newly-established community of King Salmon; then, in 1959, he moved into the Alaska Pioneers' Home in Sitka, where he died on Christmas Day, 1962. [49]

23) Monsen Line Cabin: As noted elsewhere, John Monsen's primary cabin complex was located on the north side of Iliuk Arm near the mouth of the Savonoski River. Two references, however, note that Monsen also had a line cabin that has been various described as "about 15 miles from the main cabin" and "15 miles to the northwest of the other cabins." If the latter claim is true, the most likely location for this cabin is on the north side of Naknek Lake, approximately five miles due north of Brooks Camp. Less likely, these directions would point to a cabin being located along the south side of North Arm, west of the Bay of Islands. No other information is available about this cabin, which was constructed sometime between 1926 and 1938. [50]

|

| Fure's Cabin, in the Bay of Islands area of Naknek Lake, was constructed in 1926. The photograph was taken in the late 1980s. HABS Photo, AKSO. |

24) Fure's Bay of Islands Complex: Roy Fure was born in January 1885 and grew up in Lithuania. He arrived in Alaska from Siberian Russia in August 1912. He soon made his way up to the Naknek area, and beginning in 1917 he began working in the fisheries, first in a cannery and later as a fisherman. He married a Native woman, Anna Johnson, in 1919.

In January 1926, Anna Fure gave birth to a girl named Marian, and later that year Roy built a one-room, 15' x 20' log cabin along the north shore of Naknek Lake in the Bay of Islands area. The family moved into the cabin late that summer and continued to use the cabin as a wintertime residence for years to come. Before long, Fure constructed an outhouse, a lumber storage shed, and a windmill nearby. The cabin and the surrounding countryside was absorbed within Katmai National Monument in 1931, but the NPS did not move to evict existing residents until the late 1930s. The Fures, however, continued to live in their cabin until 1940, when Roy was arrested for violation of the game laws. In response, he either built or moved into a new cabin outside of the monument's boundaries; this cabin was located on the east bank of American Creek, approximately seven miles from where it flows into Lake Coville. [51] Despite his arrest, however, he continued to use the Bay of Islands as well as the American Creek cabin; this use certainly continued into the early 1950s and may have continued for the rest of his life. [52]

Fure died in Portland, Oregon in October 1962. When he died, many personal items remained untouched in the cabin, but the following summer a bear broke in to it; as a result, an NPS ranger stored a number of those items in a nearby cache and made a number of ad hoc repairs. By 1969, the agency was using the site as a patrol cabin and was proposing the site for future visitor development. [53] The cabin remained unused and abandoned until 1975, when NPS architect Robert Carper visited the site as part of a List of Classified Structures inventory. Soon afterward, NPS officials photographed the site and placed "several items from the cabin" in the monument's small museum. [54] In recognition of the value of both the cabin and the artifacts it contained, and knowing full well that the cabin lay along an increasingly popular canoe portage, the NPS moved to document and preserve the cabin. Specialists visited the site in both 1982 and 1983. NPS cabin builders, in 1987 and 1988, disassembled the structure, replaced unsound logs, and then reassembled it. Five years later, similar restorative work was completed for the windmill and outbuildings. [55]

In February 1985, Fure's Cabin (AHRS Site No. XMK-050) was entered onto the National Register of Historic Places. Based on additional research, new material was added to the National Register nomination, which was accepted by the Keeper of the National Register on May 19, 1989.

25) Buckley Cabin: When the National Geographic Society explored the lakes west of the newly-designated monument in the summer of 1919, they visited the Bay of Islands area. While there, they discovered a cabin, built by "Mr. Buckley," which was located "on Island Bay near Portage leading to Lake Grosvenor." The expedition used the cabin as a temporary camp while surveying the area and took nine photographs of the rude cabin. So far as is known, no visitor since 1919 has made note of this cabin, and available documents have provided no additional information about Mr. Buckley. The site of this cabin, which is almost certainly collapsed by now, is in the general vicinity of Fure's Bay of Islands Complex. [56]

26) Hartzell's Lake Coville Cabin: John Hartzell was born in Finland about 1891 and moved into the Naknek area about 1927 and began working as a commercial fisherman. According to data compiled as part of A. C. Kinsley's investigation, Hartzell moved to a site on the north shore of Lake Coville on August 4, 1930 and soon afterward constructed a 22' x 24' cabin. For several years thereafter, he lived on the land each winter. By 1936 he had built another cabin along American Creek (see Hartzell-Fure Cabin).

|

| The 1919 National Geographic Society expedition encountered "Buckley's Cabin on Island Bay near the portage leading to Lake Grosvenor." This cabin, was located near where Roy Fure built his Bay of Islands cabin in 1926. University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 6, 7369. |

Kinsley, in his 1939 report, ruled in Hartzell's favor and stated that he had the legal right to live (though not trap) at his Lake Coville cabin. Hartzell apparently responded to Kinsley's investigation by abandoning that cabin. Sometime during the late 1930s he may have moved his operations up to his American Creek cabin, which was outside of the national monument; or, alternatively, he may have abandoned both of his cabins and left the area. [57] Details of Hartzell's later life are unknown.

No information is available to positively identify the cabin's location. The information he provided to Kinsley indicated that his Lake Coville cabin was along the lake's northern shore; the map that accompanied his application, however, shows the cabin as being several miles north of the shoreline, midway between the east and west ends of the lake.

27) Fure Line Cabin: As noted elsewhere, Roy Fure built a cabin in the Bay of Islands area in 1926 and lived there until 1940. But when he was arrested that year for trapping in the monument, he was forced to move elsewhere. In response, he moved to American Creek and lived in a cabin approximately seven miles from Lake Coville. This line cabin, which is located near a slough not far from the American Creek mouth, was probably built shortly after he moved to his American Creek cabin. It was probably used on an intermittent basis until Fure's death in 1962.

Mike Tollefson, who visited and photographed the site in July 1975, described the cabin as "a very small structure built in the same style as the others" (i.e., the same style as Fure's two other cabins. He made this statement, however, despite not having seen Fure's larger American Creek cabin.) He noted that "although it was not measured I would guess it is about 7' x 7' square." Later, in 1994, a List of Classified Structures survey (XMK-088) recorded a 9'11" x 8' log cache resting on the ground at this spot.

28) Hartzell-Fure Cabin Complex: As noted elsewhere, John Hartzell built a cabin along the Lake Coville shoreline in 1930 and began a wintertime trapping lifestyle. By 1936, he had expanded his operations to the point that he had constructed a new 17' x 21' cabin "several miles up American Creek" and had also established a 15' x 30' garden. (His questionnaire to Kinsley, ironically, says he worked the garden each year from 1931 to 1935 even though he worked as a commercial fisherman and made no attempt to claim that he spent his summers at the American Creek cabin). Hartzell appears to have responded to the Kinsley investigation by either abandoning his Lake Coville cabin in favor of his American Creek abode or by abandoning the area entirely. Inasmuch as no later information has surfaced about his activities along American Creek, he may well have vacated both locations by 1940.

The same investigation that caused Hartzell to move also affected the lifestyle of Roy Fure, who lived on Naknek Lake at the southern end of the Bay of Islands portage. Fure, in response to his 1940 trapping arrest, sought a location just outside of the monument boundaries, and by 1941 he had relocated to a cabin along American Creek. Fure himself stated that he built the American Creek cabin. But based on both the size and location of Hartzell's American Creek cabin (as stated to an Interior Department investigator in the late 1930s), Hartzell may well have been the cabin's actual builder.

As has been alluded to elsewhere, Fure's move from his Bay of Islands cabin to his American Creek cabin was by no means permanent, and for the next two decades, Fure appears to have divided his time while in the lakes country between these two cabins. Fure (or possibly Hartzell) added a root cellar and sauna at the site. Fure continued to use this cabin, on at least a part-time basis, until his death in 1962. The cabin lay unused for the remainder of the decade.

|

| When NPS investigators in 1993 visited Agate Point, at the northwestern end of Nonvianuk Lake, they photographed this cache, which may have been constructed by prospector Billl Hammersly. LCS Katmai file, AKSO. |

In 1971 Naknek resident John T. Graham began to occupy it. Graham, who for obvious reasons soon became known as "Trapper Jack," spent the next several winters as a squatter there, using the two-room cabin as a fur-processing site as well as a dwelling. Graham, who was known to NPS officials throughout this period, added a trap shed and outhouse to the existing improvements. He continued living there until 1977, when NPS personnel told him that he would need to leave the property. The agency gave two reasons for its decision. First, he had no legal rights to the land, and second, because Congress was proposing to include the area surrounding the cabin as in an expanded park, it was unlikely that the cabin site would be open to trapping again. Given that ultimatum, Graham left the area and returned to Naknek, and the cabin has remained vacant ever since. [58]

The cabin complex, because of its relatively recent use, is relatively easy to locate (it is approximately seven miles upstream from Lake Coville) and has recently been recorded onto the List of Classified Structures (AHRS Site No. XMK-087).

29) Lake Grosvenor Cabin: Virtually nothing is known about any trappers, trapping cabins, or trapping activity that may have existed along Lake Grosvenor. The only suggestion of such activity is contained in a single item of government correspondence from the spring of 1940. In that memo, F. A. Davidson of the Bureau of Fisheries warned the NPS that "winter trap-line cabins are at present established on the northeastern shore of Grosvenor Lake" as well as other sites in the monument. No information was provided as to where along the shoreline a cabin site may have been located. [59]

Trapping in the Alagnak River

Basin

30) Marlette Cabin: Jim Marlette, a trapper and prospector, first came to the attention of NPS authorities in March 1948 when Fish and Wildlife Service agent Carlos Carson alerted the Mount McKinley National Park superintendent that Marlette had "a sizable illegal beaver cache in [the monument] and which he is expecting to get out soon. Of course they were caught in the park." Carson did not indicate where the cache was located, and there is no indication that Marlette (who had an airplane) had a cabin in or near the monument. Later that year, Carson also heard about Marlette's apparently successful prospecting activities inside the monument boundaries. Marlette, during this period, was apparently basing his activities along the mile-long Kulik River that connected Kulik and Nonvianuk lakes. In 1983, during the Melgenak hearings, Elmer Harrop testified that "During the 1950s, the Eskimo people were run off their land by Northern Consolidated [Airlines] and the NPS. I know that Jim Marlett [sic], who had a cabin on the Kuklik [Kulik] River, had his cabin destroyed in about 1950. He was the first person I know whose cabin was destroyed." [60]

31) Neilsen Cabin: Prior to the passage of the Alaska Native Claim Settlement Act, Johnny Neilsen established a Native claim along the north shore of Nonvianuk Lake, approximately six miles west of Kulik Lodge. A decade or so later (i.e., during the early 1980s, according to the List of Classified Structures report), Neilsen constructed a milled-log, 8' x 10' cabin and an adjacent outhouse in a protected cove on his allotment. After working out of his cabin for awhile, however, Neilsen came to the realization that the area was not good trapping territory, so he abandoned the cabin and let his allotment application lapse. The cabin and outhouse were evaluated by LCS personnel in 1993. The two buildings at that time were judged to be in good condition, and the report suggested that "the park would like to maintain the cabin as a cultural resource." [61]

32) Murray Cabin: Sam Murray was an early area trapper. He was apparently well acquainted with the Nonvianuk River and American Creek drainages. (Murray Lake, upstream from Hammersly Lake in the American Creek drainage, is named for him.) In June 1933, an Anchorage newspaper noted that he was "working as a cook for hunters flying into the Kulik Lake area for bear hunting." Four months later, he was flying along with another hunting party that narrowly escaped disaster; their plane was forced to land in a remote area, and Murray "struck out" from there and helped rescue the remainder of the party. [62]

Murray built a cabin along the southern shore of Nonvianuk Lake (AHRS Site No. XMK-086); its specific location is just west of the mouth of a small stream in T14S, R37W, Sec. 9, SE. As noted in a List of Classified Structures survey, the site consists of a log cabin (approximately 10' x 34'), two caches, and a lumber scatter. The LCS survey, conducted in 1994, does not suggest a date for the cabin; considering the additional historical data that has become available and general trapping trends, it is likely that the cabin dates from the 1930s or late 1920s.

|

| Above: Wedding photograph of Sam Murray and wife Annie. Photo courtesty of Alvin Aspelund, Sr. NPS-LACL Photo Collection. |

33) Agate Point Tent-Cabin Complex: In June 1983, an NPS ranger located "one old log cache and two tent cabin frames" along the north side of Nonvianuk Lake, just west of Agate Point. [63]

(This point, the name of which is not recognized by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, protrudes southward into the lake approximately four miles northeast of the lake's outflow into the Nonvianuk River.) The specific site of the cabins is T13S, R37W, Sec. 17, SW, while the cache is located in Sec. 18, NW of the same township. "Bill" Hammersly (see below) may have lived at this site prior to 1945, when he settled at the "Hammersly Cabin" site adjacent to where Northern Consolidated Airlines would later establish one of its concessions camps.

34) Hammersly Cabin Complex: Rufus Knox "Bill" Hammersly came to Alaska in 1926 and immediately settled in the Iliamna country. By 1933, he was known as an "Iliamna trader," in large part because he ran a store at the lower end of Iliamna Lake, at Igiugig. [64] For the next few years he trapped and prospected around the Bristol Bay country; during that period, in 1938, he discovered a new placer gold deposit along American Creek, near where Alex Grant had first found "colors" in 1918. In early 1945, he settled at a site on the right bank of the Nonvianuk River at the outflow of Nonvianuk Lake. According to the land records, he remained there for ten months each year until 1952. During that time he built a 12' x 20' cabin (later expanded to 20' x 20' dimensions), a cache, and a root cellar. [65]

|

| Bill Hammersly built a cabin in 1945 at the western end of Nonvianuk Lake. By 1993, the cabin had significantly deteriorated. LCS Katmai file, AKSO. |

In 1950, Northern Consolidated Airlines established a fishing camp just below his cabin complex. Beginning that year, the company hired him as a promoter of its fishing camps, a big-game hunting guide, and the Nonvianuk Camp manager. The following year, a guest at the camp noted that Hammersly had a "cozy log cabin ... and Bill had a barabara under construction. The log framework was already up and part of the sod in place." [66] Hammersly apparently severed his affiliation with Northern Consolidated after the 1952 season, but he continued living at his cabin at least a few months each year. He died at the Veterans' Administration Hospital in Los Angeles, California, in June 1959.

The establishment of the Nonvianuk concession camp, and the crowds it attracted, may have hastened the deterioration of Hammersly's cabin complex, particularly after his death. In the 1990s, the cabin (AHRS Site No. ILI-082) was visited by List of Classified Structures surveyors, who noted that the main building in the complex had dimensions of 8'6" x 26', to which was attached a 14'6" x 14'6" main living area. Portions of the cabin's roof and walls are missing.

|

| This guide camp building, photographed in 1984, was located toward the northern end of Barbara Peterson's Native allotment along the Alagnak River. NPS-LAKA Studies Center Collection. |

35) Peterson Cabin: Barbara Peterson has a cabin on the right bank of the Alagnak River. The cabin, locally known as a trapper's cabin, is located in the middle of her Native Allotment. NPS personnel visited and photographed the cabin in 1984 and 1987; those photos show that the cabin was constructed of rude logs and a corrugated metal roof. No information is available about who constructed the cabin or when that construction took place, although it probably predates 1950. The cabin is standing but is in deteriorating condition.

36) Guide Camp Cabin: Near the north end of Barbara Peterson's allotment is a plywood, shed-roof building that NPS personnel have described as being associated with a guide camp. Agency personnel visited and photographed the site in 1984 and 1987. No information is available about who constructed the cabin or when that construction took place, although its condition and construction style suggest that it was built in the past thirty to forty years.

37) Apokedak Cabin Complex: Nick Apokedak has a historic cabin and cache on his Native Allotment near the right bank of the Alagnak River. NPS archeologists visited, mapped, and photographed the site in June 1997 (see AHRS Site No. DIL-160). No architectural or historical details about the cabin are known.

|

| One of the major points of interest along the Alagnak River is the Agnes Estrada cabin complex, as shown in this 1984 photograph. NPS-LAKA Studies Center Collection. |

38) Estrada Cabin Complex: On the Agnes Estrada Native Allotment are located a cabin, boat house, shed, outhouse, trash pit, mound, and the "outlines" of previous rectangular buildings or other disturbances. Ms. Estrada's main cabin is clearly visible and is easily identified by those passing by on the Alagnak River. The complex was visited and photographed by NPS personnel in 1984. Thirteen years later, an archeological team surveyed the site (AHRS Site No. DIL-163) in search of prehistoric and historic resources. Neither visit, however, gleaned information about the history of the structural complex. An area guidebook notes that a "landmark" along the Alagnak River is "Agnes Estrada's rustic log cabin," where "you may see caribou antlers hung over the door." It stated that Estrada lived in the cabin for most of her life, snaring animals until she was nearly 90 years old. [67]

39) Andrew Cabin Complex: Two miles downriver from the Estrada Cabin Complex is a cabin on Wassillie Andrew's Native Allotment. This cabin, like Estrada's, is along the river's right bank and a sign on the cabin wall plainly identifies the cabin's owner. The cabin's walls are composed of rough-hewn logs, while its roof is corrugated metal. At least one outbuilding lies nearby. The cabin was visited and photographed by NPS personnel in 1983, 1984, and 1987. Nothing is known about the history of the structures on the property.

40) Lower Alagnak River Cabin Complex: In 1997, NPS archeologists located and identified a complex of historic and prehistoric items (AHRS Site No. DIL-161) along the right bank of the Alagnak River, near the lower end of the Alagnak Wild River. Historic resources included a cabin, two outhouses, a shed, collapsed sauna, and historic debris. This site, unlike the other five along the Alagnak, is not located on a known Native allotment. The investigators noted that the cabin "appears to have been built circa 1940 and has seen occasional use but is currently in a state of disrepair, and the outbuildings are in a deteriorated condition."

Historic Property Summary and

Recommendations

|

| NPS personnel visited the Wassillie Andrew cabin, along the Alagnak River, in 1984. NPS-LAKA Studies Center Collection. |

Because several of the listings above refer to more than one cabin site, the list gives reference to a total of some forty-nine trapping or subsistence cabins. Of that number, however, only nineteen of those sites have been visited and documented by cultural resources personnel, and the exact location of most if not all of the thirty remaining properties is unknown. Therefore, the first priority related to this theme is to rediscover as many of these sites as possible (either by additional historical research or by field investigation); once discovered, they need to be surveyed and evaluated by cultural resources personnel.