|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

INTRODUCTION

We could not avoid remarking that the whole of this exterior coast seemed to wear a much more wintry aspect than the countries bordering on those more northern inland waters we had so recently quitted. — George Vancouver, 1794 [1]

In 1967, on a flight between Anchorage and Seward, Bailey Breedlove of the NPS gazed out over the glaciated seaboard of the Kenai Peninsula. The coast reminded him of his World War II missions performed in the terrain of the Norwegian fjords. Moved by the striking resemblance between the two subarctic coastlines, Breedlove collaborated with an associate to pen the name Kenai Fjords. [2] Several years later, in 1972, an NPS photographer was asked to capture on film the "new world" of Kenai Fjords following the passage of ANCSA in 1971. Try as he may, however, the man was unable to find Breedlove's Norwegian-like coast on any map. In his published account of the adventure he demands, "...but where-the-hell is Kenai Fjords?" [3]

By the late 1970s, the definition and boundaries of an actual area called Kenai Fjords had evolved as a planning term for the glacial system of the Pacific coast of the Kenai Peninsula in the Secretary of the Interior's 1977 proposal for the Kenai Fjords National Park. In the words of Don Follows, the NPS "keyman" for the proposal, the contrived name identified a place "that collectively described the peninsulas, bays, island stacks, and deep water fjords between the Kenai mountain platform and the wave beaten coast thrusting into the Gulf of Alaska." [4] Follows scrutinized the coastline with the hope of locating some "place" associated with the fjords. After analysis of both USGS maps and bulletins and bibliographies, Follows conceded that he could not find "a single place name there" to generally describe the coastline in this area.

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter conferred national monument status to 652,000 acres of glacial fjord ecosystem on the southeastern flank of the Kenai Peninsula. In 1980 Congress, acting under Section 203 of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), Public Law 96-487, established Kenai Fjords National Park as a new unit of the national park system. The park boundaries were drawn to reflect geologic and topographic features resulting from the creation of a glacial ecosystem, and not for any significant archeological or historic resource. [5] Section 201(5) of the law specified that the park be managed "to maintain unimpaired the scenic and environmental integrity of the Harding Icefield, its outflowing glaciers and coastal fjords and islands in their natural state; and to protect seals, seal lions, other marine mammals, and marine and other birds and to maintain their hauling and breeding areas in their natural state free of human activity which was disruptive to their natural processes." The need to protect the area's cultural resources was not specifically mentioned; the presence of humans, as noted above, was specifically cited as being detrimental to the park's goals.

In 1984 the park's General Management Plan identified historic resources and created historic zones. As described, these zones "are designated for the preservation, protection, and interpretation of cultural resources." The plan specified the establishment of a historic zone around abandoned mining properties in the Shelter Cove area of Nuka Bay, which constitutes one concentration of historic properties in the park. [6]

Several towns and villages outside the park have long had a role in the use of park resources. Seward is the principal gateway to the park. Located at the head of Resurrection Bay three miles east of the park boundary, the town has approximately 3,100 residents. Situated to the west of Seward on the tip of the Kenai Peninsula are the Alutiiq villages of Nanwalek, formerly called English Bay, [7] and Port Graham. These two villages are close to parklands and have cultural and ancestral affiliation to lands within park boundaries. The village of Seldovia, on the peninsula's western coast, also has historic association with cultural patterns within park boundaries.

|

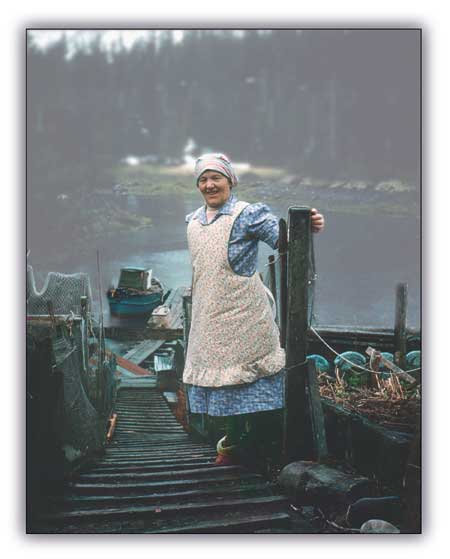

| Josephine Sather at her Home Cove residence. Anchorage Museum of History and Art. |

The predecessors to the residents of Nanwalek and Port Graham have been living in the area for hundreds if not thousands of years. Relatively little is known of the Unegkurmiut, an independent relation of the Alutiiq Pacific Eskimo, who inhabited the Kenai coast prior to and concurrent with early Russian period contact. At a later date the coast may have been settled by an amalgam of people from Kodiak Island, Cook Inlet, and Prince William Sound, in addition to the original inhabitants at the time of Russian contact.

Archeological evidence of Pacific Eskimo village sites in the outer protected bays of the peninsula indicates a pattern of habitation that was shattered by Russian acculturation and control. The fate of these villages likely followed a pattern of depopulation, disease, consolidation, and relocation that was also inflicted on the coastal village communities of Kodiak Island, the Alaska Peninsula, and Prince William Sound in the early and mid-nineteenth century. In the 1930s, American anthropologist Frederica de Laguna conducted archeological site surveys in the area; most were in Prince William Sound with general reference to the people of the Kenai Coast. In 1954, Danish ethnographer Kaj Birket-Smith collaborated with de Laguna to compile anthropological information on Prince William Sound.

Many sources have suggested that Native inhabitants of lands within the park moved away by the end of the nineteenth century. Others have indicated that the Kenai Mission of the Russian Orthodox Church supported the relocation of the last villages in Nuka and Aialik bays around the turn of the century to the more populated villages of Port Graham and English Bay. This initiative by the Russian Orthodox Church may have been aggravated by a collapse in fur prices and the consolidation of fur companies at Seldovia, English Bay, and on Kodiak Island, requiring hunters to pool resources. But summer and seasonal occupation of village sites, hunting and fishing grounds, and the use of trade routes continued. Local Native place names provide reference to land use areas. The same analogy holds true for Russian, English, Spanish, and American names of sites, landforms, passes, and waterways in and adjacent to parklands.

The exploration of the coast by Europeans is poorly documented. Russian, English, and Spanish mariners regularly shared information on the coastal areas of Alaska, especially those areas that were the most treacherous. As a result, many personal accounts are generalizations of what others had seen. Many who wrote about the outer Kenai Peninsula never actually saw it. Therefore, most accounts have little historical value because the date of a publication usually had little connection to when the information was originally recorded. This practice perpetuated what can only be called myths about the outer Kenai coast. Also, several original reports have been lost. Russian governor, surveyor, and cartographer Mikhail D. Teben'kov reported in the accompanying Notes to his Atlas of the Northwest Coasts of America [1852] that of the five Russian surveys conducted of the coast since the 1790s, three had already been lost. [8] These lost surveys may well have had more detail than the larger coastal descriptions that have survived.

In several accounts, rough seas and fog settled in as eastbound ships passed Nuka Island. The fog stayed until Montague Island and the waters of Prince William Sound appeared on the horizon. For those who dared to venture close to shore, hidden rocks seemed to lay in wait, ready to snag the hulls of the large wooden ships. Naturally wary of a coast that was difficult to navigate and formidable in appearance, George Vancouver in 1794 noted that the coast was colder and had a more "wintry aspect" than the surrounding areas. [9]

Settlement along the coast was sparse. The Pacific Alutiiq probably migrated to the area from neighboring regions; few of them, however, settled along the outer coast. The Russians built the Voskresenskii Redoubt in Resurrection Bay only after exhausting other possibilities in Cook Inlet and on Kodiak and Afognak islands.

With no established ports or villages along the coast, and with ice flow from tidewater glaciers a constant threat, Russian, European, and American traders depended on Native crews to hunt close to shore. These crews navigated the coast in fleets of small skin boats. Kodiak Island served as the primary headquarters. Many of the furs obtained from the outer Kenai Peninsula fell into Russian, European, and American hands by barter and trade.

Nineteenth century Russian fort settlements occupied the more temperate climates and harbors of Cook Inlet, and forested islands from Prince William Sound to southeastern Alaska. Although Grigorii Shelikhov's chief administrator, Aleksandr A. Baranov, supervised the construction of a fortified settlement and ship building yard in Resurrection Bay in 1793-1794, subsequent Russian governors ordered the dismantling of the artel and moved its residents to a site west of Cook Inlet, near Iliamna Lake. The move, made after 1820, reflected a change in Russian demographics and economics that favored a more centralized approach to settlement.

Since 1900 the Kenai coast has been influenced by a variety of cultural agents. Americans who traveled to the area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries endured many of the same challenges faced by the Natives and Europeans. Local traders and hunters, for example, continued to exploit land and marine mammals. In 1903 railroad speculators established the town of Seward, one of the first planned cities in Alaska. Mining and fur farming activities have had an important, if temporary, impact on the open and wild lands fronting the Gulf of Alaska. First in the mid-1850s, and then later in the early twentieth century, geologists and gold miners tenaciously explored the peninsula in the hopes of finding economically productive claims. They found little, however, and by World War II most activity had ceased. After the war, use of the peninsula remained opportunistic, and in many ways sheltered from view. Only in recent years have sport fishers, sightseers, and other outdoor recreationists brought a previously-unforeseen level of exposure to the area's coastal and glacial resources.

kefj/hrs/introduction.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002