|

Kings Mountain National Military Park South Carolina |

|

NPS photo | |

By 1780 the northern campaign of the American Revolutionary War had been fought to a stalemate, and England turned its military strategy toward the South. The tactic seemed simple: re-establish the southern royal colonies, march north to join loyalist troops at the Chesapeake Bay, and claim the seaboard. But a sudden battle in the wilderness exposed the foil of England's scheme and changed the course of this nation.

In late September 1780 a column of mounted Carolinians and Virginians headed east over the Appalachian mountains. They wore hunting shirts and leggings, with long, slender rifles of the frontier across their saddles. They came full of wrath, seeking their adversary of the summer—British Maj. Patrick Ferguson and his loyalist battalion. This time, they came to battle him to the finish.

These men hailed from valleys around the headwaters of the Holston, Nolichucky, and Watauga rivers. Most were of Scots-Irish ancestry, a hardy people who were hunters, farmers, and artisans. Years earlier they had formed settlements that were remote and nearly independent of royal authority in the eastern counties. Fiercely self-reliant, they were little concerned or threatened by the five-year-old war fought primarily in the northern colonies and along the coast.

Britain's Thrust to Regain the South

In early 1780 England turned its military efforts to the South. At first the British forces seemed unstoppable. In May Sir Henry Clinton captured Charleston, S.C., the South's largest city. The British quickly set up garrisons, using military force to gain control. Before 1780 only scattered incidents of torture and murder had occurred in the Carolinas, but with the return of the British army the war in the South became brutal. Loyalists (tories) plundered the countryside; patriots (whigs) retaliated with burning and looting—with neighbors fighting each other. The British believed that the southern colonies teemed with loyalists, and they were banking on those supporters to persuade reluctant patriots to swear allegiance to the Crown. Gen. Lord Cornwallis ordered Maj. Patrick Ferguson, reputed to be the best marksman in the British Army, to gather these loyalists into a strong militia. Ferguson recruited a thousand Carolinians and trained them to fight with muskets and bayonets using European open-field tactics. In the summer, as Ferguson roamed the Carolina upcountry, frontier patriots swept across the mountains to aid their compatriots of the Piedmont.

In August Cornwallis routed Gen. Horatio Gates and patriot forces at Camden, S.C. Learning of the defeat, the frontier militia went home to harvest crops and strengthen their forces. Taking advantage of their departure, Cornwallis mounted an invasion of North Carolina. He sent Ferguson, commander of his left flank, north into western North Carolina. In September Ferguson set up post at Gilbert Town. From here Ferguson sent a message to the "backwater men" (over-mountain patriots) threatening to kill them ail if they did not submit. Enraged, they vowed to finish Ferguson once and for all.

On September 26 returning over-mountain forces gathered at Sycamore Shoals under Cols. William Campbell, Isaac Shelby, Charles McDowell, and John Sevier. The next morning they began an arduous march through mountains covered with an early snowfall. They reached Quaker Meadows on October 1 and joined 350 local militia under Cols. Benjamin Cleveland and Joseph Winston. Ferguson, learning from spies that the growing force was pursuing him, headed toward Charlotte. The patriots reached Gilbert Town on October 4, but soon discovered that Ferguson had abandoned his camp. They rode on, reaching Cowpens on October 6, where they were joined by 400 South Carolinians led by Colonel Williams and Colonel Lacey. Ferguson's trail had been hard to follow, but now they learned that he was near Kings Mountain—only about 30 miles away.

Ferguson reached Kings Mountain on October 6, where he decided to await his enemy. Kings Mountain—named for an early settler and not for King George III—is a rocky spur of the Blue Ridge rising 150 feet above the surrounding area. Its forested slopes, sliced with ravines, lead to a summit, which in 1780 was nearly treeless. This plateau, 600 yards long by 60 yards wide at the southwest and 120 yards wide at the northeast, gave Ferguson a seemingly excellent position for his army of 1,000 loyalist militia and 100 red-coated Provincials.

Turning Point in the Carolina Wilderness

Fearing that Ferguson might escape again, the patriots selected 900 of the best riflemen to push on, with Campbell of Virginia as commander. They rode through a night of rain—their long rifles protected in blankets—and arrived at Kings Mountain after noon, Saturday, October 7. The rain, now stopped, had muffled their sounds, giving Ferguson little warning of their approach. They hitched their horses within sight of the ridge, divided into two columns, and encircled the steep slopes. About 3 pm Campbell's and Shelby's regiments opened fire from below the southwestern ridge. The loyalists rained down a volley of musket fire, but the forested slopes provided good cover for the attackers. The patriots, skilled at guerrilla tactics used on the frontier, dodged from tree to tree to reach the summit. Twice, loyalists drove them back with bayonets. Finally the patriots gained the crest, driving the enemy toward the patriots who were attacking up the northeastern slopes.

Surrounded and silhouetted against the sky, the loyalists were easy targets for the sharpshooters and their long rifles. Punishing his horse, Ferguson was everywhere, a silver whistle in his mouth trilling commands. Suddenly several bullets hit Ferguson. He fell, one foot caught in a stirrup. His men helped him down and propped him against a tree, where he died. Captain DePeyster, Ferguson's second in command, ordered a white flag hoisted but, despite loyalist cries of surrender, the patriot commanders could not restrain their men. Filled with revenge they continued to shoot their terrified enemy for several minutes, until Campbell finally regained control.

The over-mountain men accomplished their mission in little over an hour. Ferguson was dead. Lost with him was Cornwallis' entire left flank. This militia, fighting on its own terms and in its own way, turned the tide on England's attempt to conquer the South and so the nation.

Ferguson and His Rifle Design

Maj. Patrick Ferguson, the only Briton who fought at Kings Mountain, was born in Scotland in 1744 and began his military career at 14. Fascinated by firearms, he redesigned the breechloading flintlock rifle to increase firing speed and reduce fouling (clogging of the mechanism). In wind and rain he fired a series of four shots per minute while walking and six per minute while standing still. In 1776 his rifle received the Crown's patent. Of the 100 to 200 rifles produced (sporting, infantry, and officer's models), only a few exist today.

Ferguson Breechloading Rifle .65 caliber. Sporting Model Ennis of Edinburgh, maker Ferguson's breechloading rifle works simply. A plug screws into the breech perpendicular to the barrel. The triggerguard attaches to the bottom of the plug and serves as a handle. To open it turn the triggerguard clockwise one revolution until the top of the plug is flush with the bottom of the powder chamber. This opens a hole in the top of the barrel. Lower the muzzle of the barrel slightly and drop a ball into the hole. Next, pour a charge of gunpowder into the cavity behind the ball. Close and seal the plug by rotating the triggerguard one turn counter-clockwise. Prime, cock, and fire.

Musket vs. American Long Rifle

Kings Mountain was the only battle in the war in which the primary weapon of the patriot forces was the American long rifle. The flintlock muzzleloading musket, called the Brown Bess, was the standard issue for the British and Continental forces because it could be fired quickly—three to four times a minute—making it the rapid-fire-weapon of the 1700s. Soldiers typically carried prepackaged paper cartridges that held a measure of gunpowder and a ball. A skilled shooter could prime, load, and fire in seconds. The musket was wildly inaccurate and only a massed volley inflicted serious injuries. In open-field warfare troops lined up two ranks deep and volley-fired until one side could finish the job with bayonets. The patriot militia (citizen soldiers) used the American long rifles that they prized at home for protection and for hunting. They were accurate but took about one minute to load. Long rifles were best used when stalking prey—a bitter lesson learned here by the loyalists.

British Brown Bess Musket

.75 caliber, with bayonet

A 1780 military musket had a smoothbore .75-caliber barrel (inside diameter)

that fired a .69-caliber lead ball. The loose-fitting ball bounced from side to

side inside the barrel when fired, causing it to wobble in flight. This gave the

musket an effective range of about 75 yards. A 16-inch triangular bayonet

completed the weapon.

American Long Rifle

.50 caliber

Rifling, the spiral grooving within the length of a gun barrel, stabilized the

lead ball in flight by forcing it to spin on its axis like a gyroscope. The long

rifle's slender barrel (about 48 inches long with a .50-caliber bore) allowed

the gunpowder to fully combust. This extra energy thrust the spinning ball

faster and farther—up to 300 yards.

Southern Campaign in the Carolinas

May 12, 1780

After a month-long siege, General Clinton defeats American General Lincoln and

captures Charleston, S.C, America's fourth largest city and commercial capital

of the South. The only Continental Army in the South—18 regiments,

including the entire South Carolina and Virginia Lines and one-third of the

North Carolina Line—is lost. The loyalists capture 5,500 men (the largest

number of patriot prisoners taken at one time), seven generals, 290 Continental

officers, and several ships. It is the worst patriot defeat of the war. Patriots

and loyalists engage in savage partisan warfare. Both sides report burning,

looting, torture, and murder.

May 29, 1780

Near Waxhaws, S.C, Col. Banastre Tarleton attacks a column of about 400 Virginia

patriots. Overpowered, the patriots raise a white flag and ask for quarter (to

show clemency or mercy to a defeated foe). Tarleton ignores their plea. The

loyalists slaughter 113, maim over 100 who are left to die, and take 53

prisoners. The massacre earns Tarleton the nickname "Bloody Ban," and "give them

Tarleton's quarter" becomes a patriot cry for revenge.

August 16, 1780

Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, hero of the 1777 battle of Saratoga, N.Y., hopes to

surprise the British garrison at Camden, S.C. In late July Gates leaves

Hillsborough, N.C, with Continentals, untrained militia, and too few provisions.

At Camden on August 16, Gates deploys 3,000 troops against Cornwall's skilled

2,000. Ill-prepared for battle, Gates's left flank militia flees, and the right

flank is overwhelmed. Patriots lose 1,100—and their general who abandons

them and quickly returns to North Carolina.

September 1780

Cornwallis begins his invasion northward. He commands the center force; Tarleton

leads the right (eastern) flank; and Ferguson leads 1,100 men on the left

(western) flank. At Gilbert Town, Ferguson dispatches a message to Colonel

Shelby of the "backwater men"—"If they did not desist from their opposition

to the British arms, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their

leaders, and lay their country to waste with fire and sword." It is a challenge

the patriots cannot ignore.

October 1780

Forces hunting Ferguson meet at Sycamore Shoals. Handpicked sharpshooters head

for Kings Mountain. African Americans also join the chase. On October 7 Essius

Bowman, a freeman, is one of the men said to have shot Major Ferguson. After the

battle many men head home, but others march the prisoners to the Continental

Army post at Hillsborough. Feelings for revenge are high. On October 14 patriots

sentence 36 prisoners to die and hang nine. Colonel Shelby pardons the rest, and

the killings cease. All but 130 prisoners escape.

December 1780

With hindsight Clinton says, "The instant I heard of Major Ferguson's defeat, I

foresaw the consequences likely to result from it." He calls it "the first link

in a chain of evils that . . . ended in the total loss of America." Ferguson's

fate weighs heavily on Cornwallis. He retreats south to his winter quarters,

giving the Continental Army time to organize a new offensive. Gen. Nathanael

Greene replaces Gates as commander of the Continental Army's Southern

Department.

January-October 1781

Greene seizes the military initiative in the Carolinas.

• January 17—Cowpens: General Morgan's army of Continentals and

militia defeats Tarleton's force of British regulars.

• March 15—Guilford Courthouse: Cornwallis defeats Greene but at such

a cost that he stops fighting and retreats to North Carolina's coast.

• May 22 to June 19—Ninety Six: Greene lays siege to Britain's

important outpost; he fails to capture the fort, but loyalists soon abandon the

garrison.

• October 19—Yorktown: Cornwallis surrenders to George Washington.

Exploring Kings Mountain

From Wilderness Battle to National Park

As news of the patriot victory at Kings Mountain spread, Cornwallis' plan to pacify the Carolinas with the help of loyalist militia had no chance for success. Patriots began to enlist, while loyalists lost courage and refused to serve. For the patriots the news was exciting and desperately needed. For the loyalists this turn of events dealt the deathblow to their cause, leading eventually to the British surrender at Yorktown.

Word of the triumph spread quickly across the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia. But it took a full month for the news to reach the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On November 7, 1780, Joseph Greer—after walking from the Carolinas and finding his way with a compass—delivered the account of the "complete victory" at the battle of Kings Mountain to the Congress.

For years the battlefield lay neglected. In 1815 Dr. William McLean, a former patriot surgeon, organized the first commemorative ceremony at the battlefield. After directing the cleanup of the site, which included reburying soldiers' bones unearthed over the years by erosion and animals, McLean dedicated a monument to the fallen patriots and to British Maj. Patrick Ferguson. In 1855 about 15,000 people attended the battle's 75th anniversary celebration. In 1880 a centennial association unveiled a 28-foot monument. But local enthusiasm waned despite these celebrations, and the area again fell into neglect.

In 1899 a new caretaker stepped in—the Kings Mountain chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The women launched a campaign to restore local interest, acquire the battlefield and surrounding land, and obtain national recognition. The 83-foot U.S. Monument was dedicated in 1909, but the federal government remained largely indifferent to the significance of the battle site. Undaunted, the DAR, local officials, and community activists continued their efforts, culminating in the spectacular 1930 sesquicentennial (150th) anniversary. In 1931 Congress established Kings Mountain National Military Park, giving the battlefield—and the men who fought here—the recognition earned so dearly in 1780.

Exploring the Battlefield and Park

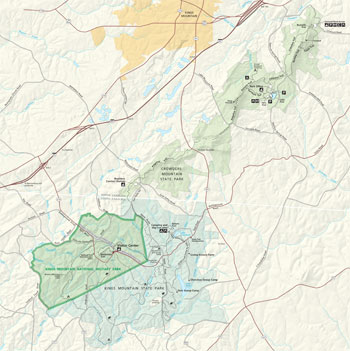

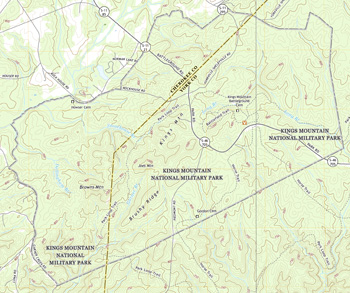

(click for larger maps) |

The Battlefield Trail The 1.5-mile self-guiding Battlefield Trail lets you see both the patriot and loyalist perspectives of the battlefield. The paved path winds along the slopes of the ridge, where the patriot forces attacked. The trail climbs and turns back across the top of the ridge, where the loyalist forces fought and surrendered. Along the way you pass markers for Major Chronicle and other patriot leaders, the 1930 Hoover Monument, the 1880 Centennial Monument, and the 1909 U.S. Monument. A granite memorial honors Ferguson of the 71st Regiment, Highland Light Infantry, as an officer of distinction. A cairn marks his grave. The trail's grade is moderate to steep. Allow about one hour to walk the loop.

Visitor Center Begin your visit here where you will find information about the battle and the park, a film, and exhibits. A bookstore offers publications about the area's military and cultural history, as well as its plants and animals. Rangers can answer questions and help you plan your visit. The visitor center is open 9 am to 5 pm daily, with extended hours in summer; it is closed on Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Accessible The visitor center, film, exhibits, and restrooms are accessible for visitors with disabilities. Although paved, the Battlefield Trail is steep in places, with severe cross-slopes: people with wheelchairs or strollers should use extreme caution. Service animals are welcome.

Activities In the summer, evening programs include concerts, ranger talks, and walks for all ages. Military encampments of the 1700s are presented on various weekends from March through November. On October 7 a ceremony commemorates the victory at the Battle of Kings Mountain.

Hiking Together the national military and state parks offer 16 miles of hiking trails and 16 miles of horse trails. Hikers should register at the visitor center before hiking on backcountry trails.

Camping The only camping allowed in the park is at a primitive backcountry site. Ask at the visitor center for information and a permit (free). The adjoining Kings Mountain State Park has a 116-site campground that is open year-round. The state park has tent, RV, and group sites.

Kings Mountain State Park The adjoining state park

offers camping, picnicking, hiking and horse trails, boat rental, and a

living-history farm with 19th-century buildings from the Piedmont area. For more

information, contact:

Kings Mountain State Park

1277 Park Road

Blacksburg, SC 29702

www.southcarolinaparks.com.

Safety and Regulations

For a safe and enjoyable visit, please observe these regulations: • Stay on

established trails to help prevent erosion. Watch out for uneven footing and

exposed tree roots. • Lightning strikes frequently on the ridge top; seek

lower ground during storms. • Drivers should look out for pedestrians; foot

traffic has the right of way. • Be alert for snakes, stinging insects,

ticks, and poison ivy. • Pets must be leashed at all times. • Horses,

bicycles (including mountain bikes), and off-road vehicles are not allowed on

hiking trails. • Applicable federal and South Carolina firearms laws are

enforced. See park website for details. • Scooters, roller blades, and

skateboards are prohibited. • Federal law protects all historical and

natural features. Metal detecting or digging for artifacts is strictly

prohibited. Do not collect, damage, or remove any plants, wildlife, rocks, or

artifacts. Please report any suspicious activity to a ranger.

In an emergency, contact a ranger or call 911.

Getting Here Kings Mountain National Military Park is on S.C. 216 in Blacksburg, S.C., just south of the North and South Carolina border. The park is 60 miles north of Greenville, S.C. and 39 miles south of Charlotte, N.C. From I-85 take N.C. exit 2; drive south on S.C. 216 and follow signs to the park.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

|

Establishment Kings Mountain National Military Park — March 3, 1931 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Socioeconomic Atlas for Kings Mountain National Military Park and its Region (Jean E. McKendry, Cynthia A. Brewer and Joel M. Staub, 2004)

Acoustical Monitoring 2012: Kings Mountain National Military Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NRR—2014/875 (Amanda Rapoza, Cynthia Lee and John MacDonald, November 2014)

Accuracy Assessment: Vegetation Information for the KIMO Vegetation Inventory Project (NatureServe, February 2010)

An Administrative History of Kings Mountain National Military Park (Gregory De Van Massey, 1986)

An Evaluation of Biological Inventory Data Collected at Kings Mountain National Military Park: Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUPN/NRR—2009/165 (Bill Moore, November 2009)

Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis, Kings Mountain National Military Park NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-97/136 (December 1997)

Bats of Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, Cowpens National Battlefield, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Kings Mountain National Military Park, Ninety Six National Historic Site Final Report (Susan Loeb, July 2007)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Kings Mountain National Military Park (2010)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: The Howser Farmstead, Kings Mountain National Military Park (2010)

Cultural Landscape Report, Kings Mountain National Military Park (Susan Hart Vincent, 2003)

Cumberland Piedmont Network Ozone and Foliar Injury Report — Kings Mountain NMP, Mammoth Cave NP and Ninety Six NHS: Annual Report 2013 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUPN/NRR—2015/1044 (Johnathan Jernigan, Bobby C. Carson and Teresa Leibfreid, October 2015)

Foundation Document, Kings Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina (July 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Kings Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina (January 2017)

General Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Kings Mountain National Military Park (October 2017)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Kings Mountain National Military Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/129 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2009)

Historic Resource Study: Kings Mountain National Military Park (Robert W. Blythe, Maureen A. Caroll and Steven H. Moffson, May 1995)

Historic Structure Report/Historical and Architectural Data: Howser House, Kings Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina (Edwin C. Bearss, June 1974)

Historic Structures Report for: CCC-Era Structures and Features at Kings Mountain National Military Park and Adjoining Kings Mountain State Park, Kings Mountain, North Carolina (Clemson University Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, March 2017)

Historical Statements Concerning the Battle of Kings Mountain and the Battle of the Cowpens, South Carolina 70th Congress, 1st Session, House Document No. 328 (1928)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Kings Mountain National Military Park, 2006 (Daniel J. Stynes, May 2008)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Kings Mountain National Military Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Kings Mountain National Military Park: Historic Handbook #22 (George C. Mackenzie, 1955, 1961)

Master Plan, Kings Mountain National Military Park and State Park, South Carolina (September 1974)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Kings Mountain National Military Park (James J. Anderson, December 16, 1974)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Kings Mountain National Military Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KIMO/NRR-2012/522 (Gary Sundin, Luke Worsham, Nathan P. Nibbelink, Michael T. Mengak and Gary Grossman, May 2012)

Non-volant Mammals of Kings Mountain National Military Park Final Report (Steve Fields, December 2005)

Re-Inventory of Fishes in Kings Mountain National Military Park (James J. English, W. Kyle Lanning, Shepard McAninch and LisaRenee English, 2012)

State of the Park Report, Kings Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina State of the Park Series No. 47 (2017)

The Howser Farmstead: Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Kings Mountain National Military Park (2010)

Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Kings Mountain National Military Park (NatureServe, January 2005)

With Fire and Sword: The Battle of Kings Mountain 1780 (Wilma Dykeman, 1991)

kimo/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025