|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park |

|

| PART II: MANAGEMENT OF THE ALASKA UNITS |

Chapter 8:

Administering the Dyea Area

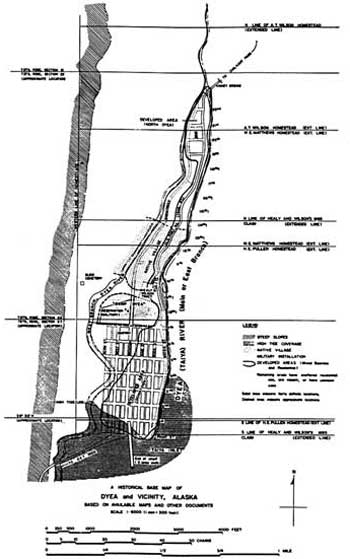

When Congress passed the act authorizing Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, the Chilkoot Trail Unit was one of the four newly-created, discontinuous park units. That unit, which is approximately 17 miles long and one mile wide, encompasses most of the Taiya River valley. At the southern end of the unit, south of West Creek and west of the Taiya River, is located the townsite of Dyea. For a short time during the winter of 1897-98, as noted in Chapter 1, Dyea boasted a population of several thousand. After the gold rush, however, it became a ghost town. Then, after World War II, the completion of Dyea Road and the desire for homesites opened the area to Skagway-area residents. The Dyea area, particularly that portion just south of West Creek and west of Dyea Road, has retained its residential character ever since.

East of the Taiya River and north of West Creek, however, the land has remained generally unsettled. As noted in Chapter 2, the lower Taiya River valley supported a timber cutting operation during the 1940s and 1950s. Otherwise, however, the only people to venture into the unit have been trappers, hunters, and Chilkoot Trail hikers.

Because the management problems of Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail corridor have been largely dissimilar, the author has decided to create separate chapters dealing with these two subjects. It is recognized, however, that some topics are equally applicable to both the Dyea area and the Chilkoot Trail corridor. For example, the various state-federal cooperative agreements and memoranda of understanding apply to the entire Chilkoot Trail Unit. In addition, several national register nominations and cultural resource surveys have pertained to both areas. In these and similar cases, the topics have been described initially in this chapter, and all material pertaining to the Dyea area has likewise been included. In Chapter 9, material has been added that specifically pertains to the Chilkoot Trail corridor.

The 1978 Cooperative Agreement

When the park bill became law in June 1976, the Chilkoot Trail Unit (which included Dyea) was controlled by a host of public and private interests. As noted in Chapter 2, most of the Dyea area was owned by private parties, and most of the land in Dyea was still composed of the same parcels that had been homesteaded prior to 1930. (The remainder, as noted above, was owned by Skagway- and Dyea-area residents, who used their land as either a primary residence or as a second home site.) Outside of Dyea, most of the land in the Chilkoot Trail Unit was owned by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. But as Chapter 3 has shown, the State of Alaska had selected most of the unit's public land in 1961. Having effective management control over the trail corridor, the state's Department of Natural Resources and Department of Health and Welfare constructed the recreational Chilkoot Trail in 1961-1963. During that period, corrections personnel constructed two cabins, near Canyon City and Sheep Camp.

Before 1976, the National Park Service was already playing a small but important role in managing the Chilkoot Trail Unit. As noted in Chapter 4, the NPS, the BLM, and the state's Department of Natural Resources had signed a cooperative agreement on August 11, 1972. That agreement had stated that the NPS "shall undertake to provide management and protection and do what may be necessary to administer, protect, improve, and maintain the lands and associated resources" in the Chilkoot Trail corridor. As a result of that agreement, Glacier Bay Superintendent Robert Howe hired two young men, Scott Sappington and Chuck Nelson, to serve as trail rangers beginning in 1973. Those men had no impact on the Dyea area; their only cabin was a shelter near Sheep Camp.

The NPS continued to employ trail rangers in succeeding years. They have, in fact, remained a summertime staple on the Chilkoot to the present day. In other ways, however, the passage of the park bill changed the management of the unit. As noted in Chapter 5, the park's authorization allowed the agency to begin purchasing land. In July 1977 the NPS bought much of the Patterson homestead, at the north end of the historic Dyea townsite. Then, eleven months later, it purchased the former Pullen and Matthews homesteads; that property, which totalled more than 335 acres, included most of the remainder of old Dyea. [1]

Regarding the remainder of the Chilkoot Trail Unit, the NPS made it known that it hoped to acquire as much of it as possible. The BLM, which owned a small parcel near the top of Chilkoot Pass, had already transferred the parcel to its sister agency. [2] The state, however, had been told in June 1974 that the BLM had approved the state's 1961 land selections, and it showed no immediate interest in divesting its interest in the trail corridor. (Given the language in the park authorization act, donation was the only transfer method possible.) Both the state and the NPS recognized that the 1972 cooperative agreement was scheduled to terminate "at such time as legislation is enacted to establish the proposed Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park or at such time as the parties hereto may hereafter agree." [3]

Given the state's continuing control over the trail corridor, both parties got ready to renew their agreement. The process that resulted in that agreement began in 1977 with Superintendent Richard Hoffman. By mid-February 1978 it had been signed by G. Bryan Harry, the Director of the NPS's Alaska Area Office, and on April 6 it became effective when signed by Robert E. LeResche, the Commissioner of Alaska's Department of Natural Resources. [4]

The new agreement was more comprehensive than the 1972 pact had been. While the initial agreement had been limited to Chilkoot Trail operations, the 1978 version gave the NPS management authority over the newly-authorized Dyea and White Pass areas as well. The agreement called on the Service "to do what may be necessary to administer, protect, improve and maintain the lands and associated resources" within the park. It demanded the permission of both parties to erect any new facilities or signs; to undertake any cultural excavations or object collecting; to provide law enforcement; to move the Dyea Cemetery (see section below); to transfer land parcels; and to prepare recreational or historical management plans. The agreement was valid for a three-year period. Consistent with the purposes of the park authorization act, the agreement decreed that lands could be transferred from the state to the federal government only by donation, and that any such transfer was subject to state legislative review. [5]

The scope of the cooperative agreement was soon broadened to cover a great deal of acreage outside of the park boundary. As noted in Chapter 4, the long-anticipated Haines-Skagway Area Land Use Plan was completed in June 1979. After the April 1978 signing of the cooperative agreement, state officials made it increasingly clear that such state-owned areas as the West Creek drainage, Nahku Bay, and the Nourse River Valley would be jointly managed by the state and the NPS. State officials apparently recognized that the federal government was better able to manage these areas than the state; as a result, they allowed the NPS to manage areas outside park boundaries so long as they first consulted with the Alaska authorities. [6]

The Dyea Cemetery Relocation

The first NPS management action undertaken after the signing of the cooperative agreement was the removal, in April 1978, of several graves from the edge of the Taiya River to less threatened ground.

The problem, which was a full-blown crisis in 1978, had been slowly incubating for years. During the gold rush, Dyea had had two major cemeteries. The Dyea cemetery, also called the town, old, or Native cemetery, had been established on a city block (between Sixth and Seventh avenues and between Broadway and West streets) when the town was laid out in October 1897. Both Natives and non-Natives were buried there. Then, in April 1898, an avalanche killed more than 60 stampeders between Sheep Camp and the Scales, and more than half of the deceased were buried in the so-called Slide Cemetery. (The bodies of the remaining victims were shipped Outside.) [7]

After the gold rush, the two cemeteries were largely forgotten. Maintenance activities at the sites were limited to a 1940 cleanup by a Civilian Conservation Corps crew, a 1950s cleanup by Skagway residents, and 1962 cleanup by a crew from the Youth and Adult Authority. (See chapters 2 and 3.) In addition, local resident William C. Matthews maintained the Dyea Cemetery. Matthews, the son of Dyea homesteader William E. Matthews, had lived in Dyea from the gold rush until the 1920s. He then moved to Skagway, where he lived until 1973. But he returned intermittently to Dyea and occasionally cleaned up the cemetery, in part because several relatives were buried there. [8]

Despite the cleanup activities, the cemeteries deteriorated. Headboards disintegrated or became illegible, grave fences were broken, and tree growth invaded. At the Dyea Cemetery, Matthews had erected a rude log fence that kept horses out, but at the Slide Cemetery, grazing and trampling took place. By the 1970s, relatively few headboards had been lost at the Slide Cemetery, but at the Dyea Cemetery, the deterioration was far worse. Only nine of the estimated 50 to 75 burials could still be identified. [9]

A worse threat was the Taiya River. During the gold rush, the river's western bank had been several hundred feet (and three city blocks) east of the Dyea Cemetery. But the Dyea townsite was laid on a relatively soft, sandy surface, and in the 1920s or 1930s a major meander developed, which resulted in the river eroding ever closer to the old burial ground. The construction of the "steel bridge" across the Taiya River, in 1947 or 1948, and the associated rip-rap installed to protect its piers permanently directed the river in a southwestern direction and toward the townsite. Major floods took place in the late 1940s, in 1953, and in 1967; each eroded portions of old Dyea. In just a few years in the 1970s, the west bank of the Taiya migrated even farther to the west, and in early 1977 it moved a full twenty feet, leaving one of the cemetery's nine remaining marked graves only eleven feet from the riverbank. The cemetery was clearly in jeopardy. [10]

Local residents had long been worried about the migrating river. In 1953, Bill Matthews had warned Governor Frank Heintzleman that the river was threatening the cemetery, three homesteads, and the newly-erected Taiya River bridge. [11] In March 1974, the problem resurfaced, and the river was reportedly "cutting dangerously close" to the city cemetery. NPS official John Rutter recognized that "the necessary rip-rapping of the river ... would involve little time and money." Until the park was authorized, however, his agency could do nothing. [12] He therefore contacted the Department of Highways, which had grading equipment, but that agency could not help because the erosion was not affecting state roads. The NPS then pressed the matter and convinced Natural Resources Commissioner Charles Herbert to talk to Highways Commissioner Bruce Campbell about the matter. In July, Campbell informed the NPS that he was requesting his department "to clean the river channel if the equipment, manpower, and funds are available later this year." Department personnel, however, were unable to respond to the commissioner's request. [13]

In 1975 Bomhoff and Associates, an Anchorage engineering and surveying firm, conducted a river engineering study for the Army Corps of Engineers. That study, completed in April, offered several alternatives for preventing further erosion damage. One called for 1,750 feet of riprap dike; the second, 900 feet of riprap plus two groins (i.e., embankments extending out into the stream); and the third, six groins. The various alternatives would cost $348,400, $375,000, and $416,000, respectively. The projected costs and the potential damage to the river's fishery resources posed by construction plans, however, prevented the state from adopting any of the study's alternatives. [14] The following year, several residents again expressed their concern about the eroding riverbank; in response, Alaska State Parks director Russ Cahill met with NPS officials and suggested that the endangered graves be moved. [15] Still, nothing was done.

A flood in 1977 further endangered the site, and that October, Senator Ted Stevens requested NPS Director William Whalen to investigate the situation. The Washington office contacted Alaskan authorities, who acted immediately. Melody Grauman, of the University of Alaska's Cooperative Park Studies Unit, was tasked to write a cemetery history. In addition, officials wrote a brief relocation plan. On January 4, 1978, Superintendent Richard Hoffman met with Terry McWilliams, the new state parks director, to discuss the situation. The two informally agreed that the best course of action would be to move the Dyea Cemetery graves to a location near the Slide Cemetery. [16]

By February 1978, the Area Office had agreed to fund the relocation project as an emergency undertaking, even though the project, being on state land, should have been the state's responsibility. (As noted above, the federal-state cooperative agreement had not yet been signed.) No decision on project specifics, however, would be made until the public had the opportunity to comment on it. [17] The public meeting took place in Skagway on April 10, four days after the signing of the cooperative agreement.

At that meeting, attended by 35 participants, the NPS proposed the removal of all of Dyea Cemetery's graves to an area just east of the Slide Cemetery. Of those that attended the meeting or submitted later comments, Steve Hites and David Hunz suggested that a far cheaper way to save the cemetery than moving the graves would be to dredge a new channel away from the cemetery; to further protect the site, they suggested that trees be cabled to the riverbank. NPS officials rejected that $6,000 idea, maintaining that it would provide only temporary relief, that it would require annual maintenance expenditures, and that it would eventually fail. All of the other meeting attendees agreed to the Park Service's proposal action except local resident Larry Jacquot. Jacquot, whose family had lived in the area for generations, claimed that a relative of his was buried in an unmarked grave; on the basis of that claim, he protested the removal of that grave from its existing site. [18]

In order to allay Jacquot's concerns, NPS officials decided to remove only the marked graves in Dyea Cemetery. Craig Davis, an archeologist in the Alaska Area Office, examined the site on April 22 and drew a rough sketch map. Davis returned to the area on May 19. He first staked out the site, near the Slide Cemetery, where the Dyea Cemetery graves would be relocated. On May 25, a backhoe dug out the new grave- sites. Meanwhile, he and a crew of local residents exhumed the remains of eight of the nine identified graves and moved to the newly-dug gravesites. (The ninth grave, of M. F. Henderson, lay under three fully-grown trees; Davis, therefore, decided to leave the grave in its place.) The project, which was completed on May 27, cost about $30,000. [19]

The grave removal project was intended as an emergency action, inasmuch as predictions had called for the river to cut 30 feet into the cemetery that year and for the entire cemetery to be washed away within three years. NPS officials, clearly alarmed at the river's impact on the historic townsite, measured the erosion rate from 1979 until 1981. Since then, erosion has been slower than expected. Even so, several graves (including the M. F. Henderson grave) washed away during the 1980s. Erosion measuring began again in 1989. In the fall of 1990, floods eroded to within ten feet of some of the major archeological features; as a result, the park's cultural resource specialist excavated a wood-lined privy the following summer. Floods in 1992 and 1994 caused additional problems, and by the fall of 1994 it was feared that the Taiya River would soon claim the gold rush-era McDermott Cabin, near the old Kinney Bridge site. [20] As of this writing, however, the cabin is still standing; a mile to the south, at the Dyea Cemetery, several unmarked graves probably still remain.

Chilkoot Trail and Dyea Landmark Nomination

As noted in Chapter 3, the Chilkoot Trail Unit was first considered for National Historical Landmark status in July 1961, when Charles Snell evaluated the area as part of the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. As part of his visit to upper Lynn Canal, he toured Dyea and then climbed the Chilkoot Trail to the top of the pass. In his trip report, he listed the "Chilkoot Trail and Dyea" site as having "exceptional value;" it was thus worthy to be nominated as a NHL. That determination, however, was left up to the Consulting Committee for the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. The committee, in turn, gave its recommendations to the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments. The advisory board, which met in April 1962, did not recommend Chilkoot Trail and Dyea as a potential NHL.

A decade later, and shortly before the first Congressional bill authorizing a national park unit was introduced, the state nominated the Chilkoot Trail (but not Dyea) to the National Register of Historic Places. The district nomination was submitted by Charles M. Brown, a staffer at the Alaska Division of Parks, on March 15, 1973. Brown's nomination was approved at the national level of significance by the National Register staff in Washington, and on April 14, 1975 it was entered onto the National Register. [21]

The National Historic Landmark designation followed shortly afterward. On December 30, 1975 and on January 3, 1976, Joan M. Antonson of the Alaska Division of Parks completed National Register forms for Dyea Site and the Chilkoot Trail, respectively. In a 1976 theme study, both the Dyea site nomination and the Chilkoot Trail district nomination were recommended as separate NHLs. The National Parks Advisory Board then combined the two nominations into one, and on June 16, 1978, the Secretary of the Interior designated "Chilkoot Trail and Dyea" as a National Historic Landmark. [22] Thereafter, officials with Alaska State Parks and the federal Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service worked to provide a site plaque. On January 25, Janet McCabe of HCRS's Anchorage office presented the NHL plaque to Rand Snure of the Skagway-Dyea Historical Society in a City Hall ceremony. Soon afterward, the NPS installed the plaque at the beginning of the Chilkoot Trail, where it remains to the present day. [23]

Preserving Long Bay

Long Bay (also known as Nahku Bay or Fortune Bay) is the only major embayment between Skagway and Dyea. The bay lies outside of the park boundary, but because of the cultural resources that lay in its waters and the scope of the recently signed federal-state cooperative agreement, NPS personnel played a prominent role in managing the cultural resources it contained.

The bay played a relatively minor role during the early months of the gold rush. On February 15, 1898, however, the bark Canada ran aground on the rocks near Dyea Point. As a result, the ship foundered and sank. During the years which followed, tides moved its hull to the bay's head, and in the 1970s it lay just below the low tide line.

Little interest was shown in either developing or protecting the bay until 1977, when Westours proposed a day boat service between Yankee Cove, north of Juneau, and Skagway. The large tour company first requested approval to moor its day boat, the Fairweather, in Smuggler's Cove, a small inlet located just north of Yakutania Point. The cove, however, was a designated city park. The city council, therefore, refused Westours' request and instead gave the company permission to dock at the small boat harbor, near the White Pass dock. It used that moorage the following summer.

Then, in November 1978, Westours announced its interest in mooring its day boat in Long Bay. Creating the moorage would require dredging by the Army Corps of Engineers; the company promised, however, that its facilities would not damage the bark Canada. Many in the city were in favor of the company's request, recognizing that Westours was responsible for funneling large numbers of tourists into Skagway. The city council, however, was opposed to the idea. [24] National Park Service historian Robert Spude, who was also opposed to Westours' plans, wrote an in-depth history of the Canada. Perhaps acting on the city's recommendations, Spude nominated the ship to the National Register of Historic Places. The city council met to discuss the matter on February 15, 1979, and despite the protestations of Westours personnel, who claimed that the dock and the boat hull were mutually compatible, council members supported the National Register nomination. [25] Westours thereafter gave up on Long Bay and instead made a second attempt to obtain a moorage permit at Smugglers Cove. The city's Planning and Zoning Commission held a hearing on the proposed action on April 2. Following the meeting, the council decided to submit the question to a public vote. On May 15, the Skagway electorate rejected Westours' request on a lopsided 161-69 vote. [26] Since that time, Westours has continued to moor the Fairweather at the small boat harbor.

Initial Planning Efforts

By the fall of 1978, the NPS had acquired the old Pullen Homestead and much of the former Patterson homestead, and it had signed a cooperative agreement with the state over management of its lands in Dyea and other areas. Given that degree of authority, Superintendent Hoffman set out to draft a Dyea area public management plan.

To Hoffman, the major problems in the Dyea area dealt with what economic and recreational activities would be allowed on the public lands. At that time, a host of activities took place there: hunting, camping, horse grazing, and the riding of such vehicles as motorcycles, four wheel drives, air boats, and snow machines.

The park's master plan gave the superintendent almost no direction on how to proceed, because it dealt only with the protection and interpretation of historic resources. The plan called for the agency to survey the historic street pattern, and remove brush from the original street alignments; to preserve, protect, and interpret the two historic cemeteries, the wharf, and the townsite; and to provide for the protection of the waterfront and tidelands, in cooperation with the state. [27]

Hoffman recognized that the Dyea flats, and the other public lands in the area, were some of the few open recreational areas available to Skagway residents. He therefore proposed to create a management plan that would allow the continuance of most existing activities. On November 26 and 27, 1978, he held public meetings in Dyea and Skagway, respectively; at those meetings, he noted that although most current land-use activities were forbidden under normal national park regulations, he hoped that local residents would be able to help determine what activities would be permitted. [28]

Following those meetings, NPS planners arrived in Skagway and began to draft a Dyea area management plan. By the following April, a draft plan had been prepared which proposed a number of land-use limitations on Dyea's public lands. The plan, laid out to twenty local residents at an April 6, 1979 public meeting, noted that the use of snowmachines would be allowed, as would in-season waterfowl hunting. In addition, the locally-organized "Dyea Country Club" would have access to the picnic area on the flats for their annual concerts. But airboats, for example, would be prohibited because of their noise, and general shooting would be eliminated as being too dangerous. Fires and camping would be restricted to designated areas, tree cutting would be limited to dead and down trees, and all park roads and vehicle trails would be open to vehicles unless closed for "pertinent reasons." [29]

Meeting participants accepted most of those restrictions. They decried, however, a proposal to restrict horse grazing. Hoffman noted that it was illegal to graze animals on the Dyea Flats; besides, he noted that the flats were severely overgrazed. In order to attract waterfowl back to the area and to "get a good stand of grass" again, he recommended that all animals in the valley be either staked or fenced on private land. Livestock owners protested the proposed plan, and suggested the implementation of a system of controlled grazing in specific areas. Hoffman, however, rebuffed their suggestions. He declared that the ban against grazing would go into effect soon. That ban, however, would not pertain to supervised grazing or to horseback riding. [30]

Despite Hoffman's prediction of the impending grazing prohibition, residents heard nothing more about that or other aspects of the management plan. As a result, residents were free to continue their traditional Dyea activities. The plan was dropped by Alaska Area officials, either because of more pressing business or because the agency, in the wake of Carter's massive December 1978 monument declarations, was in no mood to issue a plan that further restricted Alaskans' access to NPS lands. The only concrete action that followed from the plan was the construction of the Dyea Campground, noted below. By the following February, when NPS planning teams met in Skagway to plan the future of the park, officials were once again decrying the need for planning. Historian Bill Brown felt that what was needed was a Dyea townsite plan, while Wil Logan, aware that Dyea had been bare of trees during the gold rush, proposed clearcutting the Dyea site in order to obtain a full-scale inventory of local historical resources. [31]

Dyea NPS Improvements

Before Congress authorized the park unit, NPS officials recognized that improvements would be necessary in the Dyea area. The 1973 master plan noted that

Dyea needs only a small interpretive structure and a few onsite interpretive devices, to be used during the visitor season. This interpretive building should be manned, for it would also function as a trailhead ranger station for the Chilkoot Trail.

The plan also called for the establishment of two small walk-in campgrounds. [32]

Just before Congress authorized the park, city council members requested NPS officials to plan for, and fund, Dyea campground facilities. Glacier Bay Superintendent (and Klondike keyman) Tom Ritter responded by requesting that "a complete study of potential campground facilities in the Dyea area be conducted soon after the establishment of the park." [33] As noted in Chapter 7, Ritter inspected several facilities himself during an August 1976 reconnaissance. He urged, however, that the NPS go no further without consulting with the state. The state, for its part, was more interested in building a campground in Skagway than Dyea. (In its January 1978 campground study, one of the six proposed area campgrounds was located near the Dyea homestead area; its author, however, played down the site because of its remoteness.) The Alaska legislature that year allotted a token amount for campground improvements, but Senator Stevens failed to gain federal support for a campground as part of Alaska Lands Act legislation. By the end of 1978, the outlook for a Skagway-area campground appeared bleak.

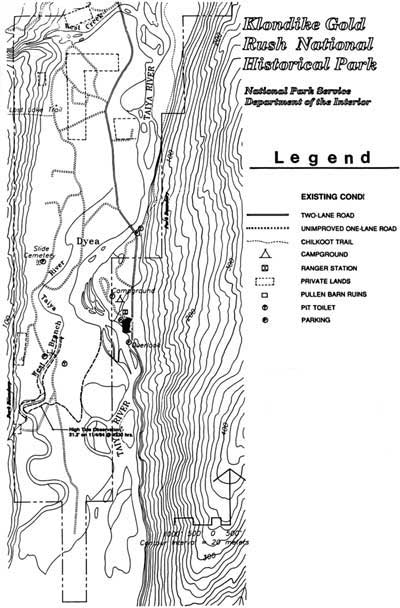

Local NPS officials responded to the rising need for campground space by creating the Dyea Campground complex during the summer of 1979. Chief Ranger Jay Cable and seasonal ranger David Hites-Clabaugh laid out the 22-space campground; adjacent to it, the park constructed small tent frames for the ranger station, two ranger cabins, a shower facility, and two outhouses. The entire campground complex was constructed on state land; its western end was within the park's boundaries but the entrance area, parking lot, picnic area, and ranger station buildings were not. Although the campground was situated on state-owned land, its construction was condoned by state officials because it was consistent with the intent of the recently signed federal-state cooperative agreement. [34]

The NPS made few improvements to the Dyea area during the 1980s. For one reason, Skagway Historic District rehabilitation was a higher priority than improvements in Dyea; this was because relatively few tourists visited Dyea and because local interests lobbied to keep funds at work in the historic district. In addition, Dyea's cultural resources were not completely known pending a thorough survey of the area, and NPS officials were unwilling to expend funds in Dyea without having a management plan in place. And regarding Dyea campground, NPS officials were less than enthusiastic about expending funds to improve an area that was on state-owned land and, in part, outside of the park. [35]

Despite those factors, the agency gradually improved the Dyea area. In 1980, rangers installed bulletin boards at Dyea campground and the Chilkoot Trail head. In 1981, the park improved the 1.5-mile road between the state-maintained Dyea Road and the Slide Cemetery, and in 1985 it made trail, fence, and restroom improvements at the cemetery. [36]

The 1979 Archeological Survey

Although Skagway residents had long considered Dyea as a popular site for bottle hunting and other informal excavations, the first formal archeological survey took place on May 29, 1975, when contractors for the Sealaska Corporation surveyed Native cemeteries and burial sites as part of a so-called 14(h)1 survey. Archeologists that day made a short visit to the Dyea Cemetery and vainly searched for nearby evidence of a Native settlement. [37]

Shortly after that survey was completed, Robert C. Dunnell, chairman of the University of Washington Anthropology Department, and Jerry V. Jermann, of the UW Office of Public Archaeology, prepared a scope of work to NPS officials for a parkwide archeological survey and inventory. (As noted in Chapter 4, the university had participated in several other studies during the mid-1970s.) That proposal, submitted on October 21, 1975, was accepted but put on hold pending the passage of the park bill. [38]

The UW proposal was discarded for the time being. But by the fall of 1977 the idea of an archeological survey had been revived, and park personnel hoped to sponsor a survey the following summer that would cover Dyea, Canyon City, and possibly Sheep Camp. [39] No survey, however, was made in 1978, and it was not until March 1979 that the NPS contracted with the UW Office of Public Archaeology for a survey. Jermann and Dunnell served as co-Principal Investigators, while Regional Archeologist Charles Bohannon represented the National Park Service.

The survey, headed by Caroline Carley, took place during the summer of 1979. Carley and her assistants, Robert Weaver and Robert King, surveyed Dyea and the major settlement sites along the Chilkoot Trail, and they made a cursory evaluation of major trailside features between Pleasant Camp and the top of Chilkoot Pass. In addition, the archeological team made a brief survey of the White Pass Unit and inventoried items at Porcupine Hill, along the Brackett Wagon Road, and in old White Pass City. [40]

During their season's work, which featured almost continuous rain, the three-person team inventoried and recorded an astonishing number of archeological features. In the Chilkoot Trail Unit, they located more than 40 collapsed or scattered structures, 27 foundations, 93 pits and 19 artifact concentrations, along with many associated artifacts. Some of those resources were located in Dyea, including 10 general features, 13 structures, two foundations, 79 pits, and two artifact concentrations. Scores of additional resources were found in the White Pass Unit. [41] The team concentrated first on those sites that were most vulnerable to visitor impacts, and made no attempt to complete a thorough inventory. The survey was completed in mid-September; a final report was completed in 1981. [42]

The same summer that Carley was at work, contract historian Robert Spude was gathering information on the Chilkoot Trail Unit's historical resources. Combining notes gathered from field work as well as from secondary source materials, he compiled historical diary and newspaper entries with an array of graphic materials to give a broad background of historical data about Dyea, Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and other sites along the U. S. side of the Chilkoot Trail. The results of his research, which included suggestions on how to preserve the trail's historical resources, were published in a 213-page volume entitled Chilkoot Trail; from Dyea to Summit with the '98 Stampeders, published in late 1980 by the University of Alaska's Cooperative Park Studies Unit. [43]

During the period which followed Carley's survey, the city of Skagway moved to annex the Dyea area and a vast area which surrounded it. Until February 1978, Skagway's city boundaries had been limited to a one square mile rectangle at the lower end of Skagway Valley, and for the next two years the city encompassed just 11 square miles, still within the Skagway Valley watershed. But beginning in mid-1978, officials recognized that if the city expanded its boundaries to encompass all of the area between Haines Borough and the Canadian border, it would be able to select state lands for its own purposes in the Taiya River valley. (It would also be able to fend off any annexation attempts by Haines Borough.) A vote to annex the area was defeated in the 1978 municipal election, but in July 1979 the city submitted a second annexation petition to the Alaska Local Boundary Commission. That petition, which was opposed by several Dyea residents, resulted in the annexation question being placed, once again, on the local ballot. More than 60 percent of Skagway's voters in the October election approved the measure, and on November 17, the commission held an annexation hearing in Skagway and accepted the city's annexation petition. [44]

The only remaining roadblock to the creation of an expanded boundary was the Alaska legislature, which had 45 days to reject the commission's action. The legislature convened in January 1980, and on February 29, the Senate Community and Regional Affairs committee held a hearing in Juneau to field public opinion on the subject. No one at that hearing, however, moved to deny Skagway's annexation petition, and soon afterward the annexation became law. Thereafter, the City of Skagway encompassed 431 square miles, and extended from the Haines Borough boundary to the Canadian border. [45]

The Dyea Land Acquisition Plan

By the beginning of 1980, as noted in Chapter 5, agency officials had completed the purchase of most of the private parcels that they had hoped to buy in both the Skagway Historic District and in the Dyea area. Then, in April 1980, Klondike Superintendent Richard Sims issued the park's first land acquisition plan. The plan, which was required for all parks that contained non-federal lands, stated that

In order to effectively prevent damage or adverse impacts to the Park's historical resources, and to properly develop and interpret the park for the public, the NPS must acquire the majority of the lands in the White Pass and Chilkoot Trail units.... Leases, zoning restrictions, cooperative agreements, scenic easements, purchase of development rights, and any other protective controls of less than clear, fee-simple ownership ... provide less than the best possible protection for the nationally significant park resources. Therefore, fee-simple title to all lands and waters except the privately owned property in the Chilkoot Trail unit of the park will be acquired. [46]

The document, which dealt with lands throughout the park, focused on lands in the Chilkoot Trail Unit. It made arrangements for a potential land exchange in order to obtain the large state-selected holdings, and it requested the transfer of BLM and Forest Service lands to the NPS. Regarding privately-held lands in the Dyea area, the document stated that

Private lands in the Chilkoot Trail unit of the Park will be acquired only on a willing seller/willing buyer basis. Normally, any private lands acquired will be purchased in fee simple. Scenic easements, development rights or other less than fee simple interests will be considered only in unusual or special circumstances.... There will be no priority system for acquiring private lands since such lands will be acquired only in instances where landowners express a desire to sell their properties to the National Park Service. [47]

The plan noted that "At least one private residence within the park appears to be located on public lands," and procedures were outlined on how such cases would be adjudicated. The plan also contained a section that outlined compatible and incompatible land uses for private landowners in the park. That section prevented "construction or development of any kind" on undeveloped land; it also prohibited "replacement of a major structure with one that is substantially different in size, location or purpose from its predecessor" on developed land. [48]

The plan was issued on April 11, and it immediately ran into a barrage of criticism, primarily in response to the "incompatible use" statement. On April 16, Dyea landowners Robert and Julie Burton wrote a lengthy protest letter to the mayor, the city council, Governor Hammond and the Congressional delegation, calling the restrictions laid out in the plan "unreasonable and unworkable." The basis for their protest was the plan's prohibition against new home construction, an activity the couple had hoped to begin in the near future. The Burtons noted that "subdividing, building homes, additions to homes and out buildings, and clearing of land for agricultural, fuel supply and safety purposes" were "rights that came to us with the deed of ownership." Each of those activities, however, were either restricted or banned in the draft plan. They further noted that since the Dyea homestead area was seldom visited by tourists and was separated by some distance from the historical townsite, "we view the regulations for inholders as set forth in the Plan as an invasion of privacy." [49]

The Burtons' cause was soon joined by Willard F. "Skip" Elliott, who had been active in the Dyea area since 1975 and was the co-owner of the Burtons' property. [50] At the April 17 city council meeting, Elliott asked the city (which by now included Dyea within its boundaries) to support the cause of the Dyea residents. The council agreed, and on April 24 Mayor Robert Messegee wrote Sims, asking for a public hearing on the subject. Jeff Brady, an editor of the local Lynn Canal News and normally a backer of NPS concerns, also railed against the plan's unfairness and called for a public hearing. Sims, who because of a bureaucratic snafu had had little time to prepare the plan, demurred on the idea of a public hearing; he claiming that there was insufficient public interest in the matter, and also noted, "What's more public than [written] comments?" Local residents, unsatisfied by his response, appealed to the Congressional delegation for help, and in early May, Acting Deputy Director Daniel Tobin was prevailed upon to schedule a public meeting. Sims dutifully repeated to a meeting of the Skagway city council that a meeting would be held soon, and as late as February 1981 he noted that the agency "fully plans to hold hearings" on the land acquisition plan. [51]

The superintendent, however, never set a date for a hearing despite repeated prodding from Elliott, and the draft plan was quietly shelved. It was not until March 1981 that an NPS official told local residents why the meeting was never held. According to Deputy Director Douglas Warnock, the delay was caused by pressing business related to the Alaska Lands Act, which cleared Congress in November 1980 and was signed by President Carter a month later. By that time Ronald Reagan had been elected president, and Reagan's appointees let it be known that a land acquisition plan was no longer required for each park. NPS officials, for their part, were glad to avoid having to finalize the plan; they certainly had no desire to face a hostile crowd at a public hearing. [52]

Meanwhile, and for several months to follow, Dyea landowners and the Park Service remained at odds on the subject. At least one Dyea resident hurried the construction of her house before any plan could go into effect. Worsening the situation was a series of policing actions by NPS officials. In April, for example, rangers conducted a series of contacts with Dyea residents concerning the legality of their land claims. [53] That summer, rangers made daily trips to the cabin of Al and Janeen Huntley, which the NPS claimed was on public land; in other cases, rangers allegedly drove onto private property and remained without asking permission. Chief Ranger Jay Cable photographed a free-ranging dairy cow belonging to John and Lorna McDermott. Finally, rangers ordered Dyea residents Lucinda Hites and Sue Hosford to stop work on a 10' x 50' community garden which was located on park land; soon afterward, the rangers took down the fence around the garden enclosure. The combined effect of those actions, trivial as they may have seemed to the NPS, caused local attitudes toward the agency to fester and sour. [54]

In the midst of this dispute, the city moved to obtain land in the Taiya River valley. The recent annexation had allowed the city to select 215 acres of land; that land was to be chosen from four parcels in the Dyea area that had recently been conveyed to the state. Once the city obtained the land, it hoped to sell it back to private owners. On August 5, city leaders met with Superintendent Sims and state officials on the matter, and two days later, the city council voted unanimously to select land from two of the four noted parcels. Area #1 was a 90-acre parcel on the north side of West Creek, while Area #2, which bordered Area #1 on the south, was a 138-acre parcel between West Creek and the mouth of the Taiya River. Area #1 was outside of the park, but Area #2 straddled the park boundary, 133 acres of it being inside the park. Mayor Messegee recognized the potential for conflict, and noted that "we're going to have a hell of a fight with the park service." [55]

The park service, as expected, protested the city's selections within the park boundary in a September 4 letter. It did so because it hoped, some day, to relocate the Chilkoot Trail in the Dyea area to its historic location on the west side of the Taiya River, and the city's selection was in the planned trail relocation area. Three weeks later, the state's division of lands acceded to the agency's request; it decided to convey only those lands in the two parcels that were outside of the park. The state sided with the NPS because the recently-completed Haines-Skagway Area Land Use Plan cited parklands as being reserved areas; it also supported the NPS because it had supported park legislation. (It may also have sided with the NPS because of the state-federal cooperative agreement, which had been in force since 1978. The agreement specifically stated that it would "in no way be deemed to be a transfer of title to any lands ... nor constitute in any way ... a relinquishment of any [title] by any of the parties." The state had no interest at that time in violating the agreement.) The city, angry at the state's decision, decided to appeal it; it also applied for an additional 153 acres farther up West Creek. [56]

As noted in chapters 6 and 7, affairs in Dyea had not been the only source of tension during 1980 between Skagway-area residents and the park service. Residents, for example, were becoming increasingly unhappy that the agency's downtown buildings were remaining unimproved, that the agency was not forthcoming about the pace of rehabilitation, and that buildings were not being leased back to private interests. Problems with the Arctic Brotherhood Hall and the administrative site exacerbated the situation. By the end of the year, the accumulated effect of problems in Skagway and Dyea had brought relations between the NPS and local residents to an all-time low.

In January 1981, Dyea resident Skip Elliott was appointed as the Skagway City Manager. Soon afterward, Dyea residents invited Charles Cushman, the president of the National Inholders Association, to share his views and expertise with them. Cushman, an inholder at Yosemite, had formed the association just three years earlier; he was invited to Mike and Sue Hosford's Dyea residence on February 15. The thirty or so inholders in the audience told Cushman, in short, that they did not like the way that the NPS had been treating them, and they cited as evidence the fiasco over the land acquisition plan, and the actions of the "gestapo" NPS rangers the previous summer. Others were upset that Richard Sims, the current superintendent, had discarded the promises that Richard Hoffman had made two years earlier during the formulation of the Dyea management plan. Cushman was able to offer a number of suggestions on how to deal with the NPS. In addition, the very fact that the meeting took place crystallized the inholders' need to react strongly to the agency's failings. [57]

Four days after Cushman's visit, Skagway city councilman Marvin Taylor reacted to the deteriorating situation by suggesting that the city write NPS Director Russell Dickenson, outlining the extent of residents' complaints and the basis for them. That same week, city manager Skip Elliott went to Juneau and testified to the Senate Resources Committee on SB 36, a National Inholders Association-supported bill that would have set up an Alaskan Citizens' Advisory Commission on Federal Areas to deal with state land management issues. Elliott used the occasion to describe the Cushman meeting and to complain of the NPS's management excesses in the Dyea area, noting that there was "not a single person in Skagway" who supported the way the agency was managing the park. The NPS, for its part, was nonplussed by all the activity. When a reporter asked Sims about his assessment of the Dyea land situation, he replied that he was unaware of any problems that existed, declaring that "I haven't had a single person in the last several months complaining about anything. I can't see that the park service has done anything detrimental." [58]

On February 27, as noted in Chapter 7, Elliott wrote Dickenson a lengthy letter detailing the concerns of local residents. He noted that "the tension that has been developing in the past several years between the city of Skagway and the National Park Service has become quite intense in the past few weeks." He noted that cooperation between the two entities still existed, but that "broken promises, inconsistencies in park policy, and poor public relations has made cooperation difficult, at best." He asked Dickenson to attend a public meeting in Skagway and

establish for the record the expected and intended level of NPS involvement in our community both politically and economically... Moreover, we would like to establish, in a legally binding manner, guarantees of specific traditional uses, guarantees that condemnation will not be used in this park, and guarantees that the Park Service will recognize the authority of the City of Skagway to plan and zone private properties within its municipal boundaries.

Elliott then proceeded to list problems that had taken place with the land acquisition plan, the use of NPS buildings along Broadway, the Dyea community garden, and the illegal placement of an NPS mobile home in the Skagway Historic District. In a dour closing note, he concluded that "These are the major issues.... Compare the mistrust and anger that exists in Skagway today to the open-armed friendliness that once existed between Skagway and the NPS. The honeymoon is over and it is time to negotiate in writing the terms of the marriage contract." [59]

While Dickenson and other NPS officials were mulling over Elliott's tome, local residents were prevailing upon their representatives in Juneau. They, in turn, prepared resolutions dealing with the Klondike situation. On March 4, 1981, the House Resources Committee introduced House Joint Resolution 26; the same day, the Senate Resources Committee introduced an identical measure, Senate Joint Resolution 25. The two resolutions listed a long litany of grievances, most of which had been expressed in Elliott's letter to Dickenson. The resolutions asked the Secretary of the Interior to "investigate promptly the charges made against the actions and policies of the NPS at the ... Park," and that the Secretary "direct the NPS to adhere to the commitments made by Congress to the people of Skagway in establishing [the] Park." Copies of the resolutions were forwarded to Interior Secretary James Watt, NPS Director Russell Dickenson, and the three members of the Alaska Congressional delegation. Neither resolution fared well; both died in committee. Their very introduction, however, alerted federal officials of the state's concerns over park management. [60]

The same day that the two resolutions were introduced, Deputy Regional Director Douglas G. Warnock flew to Skagway to resolve the issues that Elliott had addressed a week earlier. Warnock conferred for more than five hours with Skip Elliott, Robert Messegee and John McDermott in a meeting Warnock described as "extremely cordial." Warnock quickly learned that the agency's attitude toward condemnation was the trio's primary concern, and he was pleased to tell them that the NPS had no interest in acquiring land in that way. He did hope that there might be a visual buffer or screen between historic Dyea and the homestead area; given current developments, however, there was no danger of that buffer being threatened.

Warnock reiterated the city's legal right to zone private lands in the Dyea area. His agency had no plans to close off access to the beach or to close any other roads in the Dyea area; he noted, however, that hunting and trapping would henceforth be prohibited and that Superintendent Sims was correct in closing down the community garden. He hoped to lease the first downtown-area park buildings in the spring of 1982, and justified the park's use of the buildings because of the lack of seasonal housing. He admitted that the NPS violated the trailer ordinance when Superintendent Sims occupied the trailer in the historic district, and he promised that Sims would move "in the near future." He defended the ranger "snooping" in Dyea the previous summer, because the agency needed to be certain that the unoccupied cabins stayed that way.

Regarding the horse grazing situation on the Dyea flats, the city officials requested that grazing be allowed to continue under a permit system, perhaps with a reduced number of animals for the 1981 summer season. As a final note, Warnock proposed that Regional Director John Cook attend a public meeting in the near future. Warnock felt that his meeting was "very worthwhile;" he received like expressions from both Elliott and McDermott as the meeting concluded. [61]

As noted in Chapter 6, Cook flew to Skagway on March 26 and appeared before a public meeting in Skagway's city hall. A crowd of 45 heard Cook expostulate the agency's positions on a variety of topics, and meeting participants listed many of the same complaints that city officials had provided two weeks earlier. The regional director, to a large extent, backed up the statements that Warnock had made, and because of his position as regional director, many of the statements he made became the NPS's ad hoc policy as soon as they were uttered. Cook, for instance, allowed the city to manage the Dyea community garden, and he sympathized with those who wanted to remove dead and down timber from park lands for firewood. But he, like Warnock, continued to insist that subsistence hunting and trapping were illegal. Those in the audience liked Cook's open, offhand style; many openly admitted that they were pro-park, but disappointed in the way things were being handled, especially in Dyea. Cook was applauded at the end of the meeting. A reporter there noted that "It was the first time a federal official had received applause in Skagway since the park was dedicated in 1977." [62]

As a result of the hubbub that began with the April 1980 issuance of the draft land acquisition plan, the NPS learned--painfully--that it was unwise to demand land-use controls from Dyea residents, particularly from those whose property did not impinge on the historic townsite area. The agency learned a great deal about what activities were important to those residents. It tried to accommodate some of those activities, but agency rules prevented the acceptance of others. The visits, in March 1981, of Douglas Warnock and John Cook did a great deal to bridge the communications gap that had separated the NPS from local residents during the previous year. Thereafter, the antagonistic feelings between the NPS and Dyea residents began to dissipate.

The West Creek Hydroelectric Project

No sooner had the NPS extricated itself from the brouhaha surrounding the land acquisition plan than the agency became involved in another Dyea land use issue. To be decided was whether a hydroelectric dam and its associated powerhouse would be built along West Creek, at the western edge of the park's Chilkoot Trail Unit.

Portions of the West Creek drainage had been logged during the mid-1960s, and since that time the area had been popular for hunting, hiking, gathering firewood, cutting house logs, and berry picking. The Haines-Skagway Area Land Use Plan, finalized in 1979, urged a continuation of those activities. That same year, however, the Alaska legislature allotted $50,000 to the Alaska Power Administration for a study of potential hydroelectric sites in the Haines area. The CH2M Hill consulting company conducted the survey and revealed several promising sites in the vicinity of Haines and Skagway. Following that study was a more intensive feasibility study, by R. W. Beck Associates of Seattle. The Beck study, which was released in draft form in late 1980, noted that most area sites showed little economic promise. A dam and power plant on West Creek, however, would be able to provide power at 28 cents per kilowatt hour, a rate that compared favorably with that which Haines and Skagway residents paid for their diesel power. Skagway, at the time, was able to rely on relatively cheap hydroelectric power during the summertime, when copious quantities of water were available. (Skagway's water source was the reservoir adjacent to Lower Dewey Lake.) But Skagway required more expensive diesel generation during the winter months, and Haines depended on diesel for power on a year-round basis. A project along West Creek promised sufficient power to satisfy the needs of both Haines and Skagway all year long. [63]

The project that Beck (and its predecessors) proposed was to be located at the north end of the Dyea townsite. The dam, which was planned to be 107 feet high, would itself be of little concern to NPS officials; the spillway would be located three miles west of the creek's confluence with the Taiya River (and two miles west of the park boundary), and the accompanying reservoir would flood 500 acres west of the dam. Other aspects of the project, however, were more worrisome to the agency. The powerhouse below the dam was projected to be inside the park boundary, at the northwestern end of the Dyea homestead area and just south of West Creek. The proposed powerplant would be located within park boundaries, in or near a two-acre parcel owned by Skagway resident Duncan Hukill. In addition, such ancillary facilities as transmission lines, a penstock and tailrace would be located within the park. [64]

The issue flared into the open in December 1980, when Alaska Power and Telephone (a utility company which served Skagway) responded to the draft report by filing for water rights on West Creek. AP&T made its filing in hopes that it might build a relatively small-scale "run of the river" power project. But others had larger ideas and protested accordingly. Haines Light and Power, the Haines and Skagway city councils, and the Alaska Power Administration (APA) all protested the filing because they hoped to see a large project built. The draft study had concluded that cheap power could only be realized if both utilities worked together, and AP&T openly declared its refusal to work with HL&P on project development. [65]

For the next several months, officials and local residents could do little but await the completion of the Beck feasibility study. Soon after it was completed, its findings were presented in public meetings that were held in Haines on April 28 and in Skagway the following day. At those meetings, Beck representatives noted that there were actually three feasible projects in upper Lynn Canal: West Creek, Goat Lake (in the Skagway River Valley), and upper Chilkoot Lake (north of Haines). Each of the projects, if built, would serve both communities; Haines and Skagway would be connected by a submarine cable. Of the three, however, the $31.6 million West Creek project was the top choice. [66]

Representatives from R. W. Beck and the Alaska Power Administration concluded that they would next seek funding to conduct a more detailed West Creek feasibility study. The Skagway City Council agreed; at its May 7 meeting, it voted in favor of APA's feasibility study, and vowed that it would try to block AP&T's "run of the river" project on West Creek. Meanwhile, the bill that would authorize the $1 million study, SB 26, wound its way through the legislature. [67]

The passage of SB 26 that year, and the purported economic feasibility of the project, heightened the expectations of local officials. Those officials recognized that for the project to succeed, however, the powerplant would not be able to be located on NPS land. As Douglas Warnock had warned in March, "such a project or crossing of park land by any portion of a power development requires approval of Congress." [68]

The topography of the area did not allow the powerplant or the transmission lines to avoid crossing the park. In order to avoid the problem, therefore, local officials proposed eliminating the Dyea area from the park. Marvin Taylor, a pro-development member of the city council, proposed that the Chilkoot Trail Unit of the park be reduced to a 100-foot strip that stretched from the Dyea trailhead to the top of Chilkoot Pass. He based his resolution on the litany of inholder problems that had recently surfaced; he was also emboldened because his suggestion that the Chilkoot Trail unit be reduced, at the March 26 John Cook meeting, won the "unanimous approval of those in attendance." At its September 3, 1981 meeting, the Skagway City Council passed a resolution calling on Congress to reduce the Chilkoot Trail Unit to a 100-foot strip. The resolution also called for the elimination of the park's White Pass Unit. [69]

Following the vote, city officials forwarded the resolution to the Congressional delegation. Senator Frank Murkowski responded by asking the NPS's congressional liaison, Ira Whitlock, to prepare a draft bill that would carry out the council's wishes. The NPS prepared the bill, which would have transferred Chilkoot Trail Unit land to the BLM and White Pass Unit land to the BLM and the Forest Service. Neither Murkowski nor others in the delegation, however, introduced it. For the moment, the proposal to delete the majority of the Chilkoot Trail Unit was dead. [70]

The passage of SB 26, as noted above, authorized the Alaska Power Administration to spend $1 million on a detailed West Creek dam feasibility study. Soon after the bill's August 4 implementation date, a contract was awarded to R. W. Beck Associates, and by September, drillers and geologists were working in the Dyea area and attempting to determine whether the geological substrate could support the proposed 107-foot dam. The contract called for a completion date of March 1982. APA officials at the time predicted that dam construction could begin as early as 1984, with the dam complete and operating in 1986. [71]

Midway through the feasibility study, on January 14, 1982, an APA representative met with Skagway residents on the project. Brent Petrie reiterated that West Creek was "financially, geologically, and environmentally superior" to either Goat Lake or Upper Chilkoot Lake as a hydroelectric site. Petrie noted that after further studies, the project would cost $55 million. The size of the proposed West Creek dam would be anywhere from 50 to 105 feet high and between 300 and 1500 feet long. The consulting company, by this time, had found two alternative powerhouse locations; the NPS site, however, was financially and geologically superior to the other two sites. [72]

Upon completion of the Beck study, representatives of APA and the consulting company returned to Haines and Skagway, where meetings were held on April 20 and 21, respectively. The project's cost, by now, had risen to $63.5 million--high enough "to scare people," noted a local newspaper story, but still cheaper than either existing systems or other energy alternatives. Officials, by this time, were predicting that construction would begin in 1986. [73]

The APA next got ready to make a formal project application to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Before it could do so, however, the agency sought to determine the extent of the cultural resources that would be impacted by project development. In the summer of 1981, Beck had contracted with Environaid, Inc. of Juneau, which had provided them with baseline data; the following May, CSPU archeologist Harvey M. Shields spent a day in Dyea performing compliance work and located "nothing of any significance." Additional data were necessary, however, so in August 1982, Beck retained Ertec Northwest, Inc. of Seattle to conduct a more extensive investigation. By mid-August, a team of Ertec archeologists had travelled to Dyea and begun their work. [74]

Action was also taken that summer to clear the legal roadblocks posed by the existence of the park. As noted above, there was no technical alternative to siting the powerplant, the tailrace, and portions of the transmission line within the park boundaries, and to avoid restrictions placed by the park, the city council had tried to eliminate the Dyea area from the park. Until the spring of 1982, APA officials had also pressed for a Congressionally-approved redrawing of the park boundaries; they also hoped to exchange NPS land in the homestead area for state land located elsewhere in Alaska. That April, however, the APA met with Superintendent Sims and discovered that the state agency might be able to obtain a permit for the powerhouse and an easement for the construction of a transmission line through the park. Sims promised them that the permitting process might be completed within a year. [75]

During the next few months, the land difficulties surrounding the proposed dam reached the office of James G. Watt, Reagan's Interior Secretary. Watt learned that similar problems existed in other Alaska parks, so on September 1, he announced a plan to exchange NPS land for state land in four Alaska parks. A total of 26,000 acres in Denali and Glacier Bay national parks, as well as 22 acres at Klondike, were to be transferred to the state in exchange for 14,000 acres near McCarthy within Wrangell-St. Elias National Preserve. Watt noted that "none of the lands being traded to the state were essential to the parks involved," and state officials frankly admitted that "we will definitely be getting more value as well as more acres." Conservationists, however, attacked the plan, noting that it was weighted in favor of economic development and that it set a bad precedent. [76]

Several weeks after Watt's announcement, state Natural Resources officials announced that a public hearing on the proposed land trade would be held in late November. But on October 8, an event took place that placed the entire project in jeopardy and made moot all discussion of the proposed land swap. The White Pass and Yukon Route railroad ceased operating that day, and soon afterward, the White Pass announced that it might not operate passenger trains in the summer of 1983. Because the White Pass was Skagway's largest single power user, its discontinuance of service caused APA officials to withdraw $350,000 that had originally been earmarked for the West Creek project. [77]

Support for the project, and the land swap, deteriorated after that point. Due to the election of a new governor, state Natural Resources personnel did not hold a public hearing on the land swap. APA and Beck officials, however, met with local citizens in early December to amend their study. At that time, the APA's Brent Petrie pessimistically noted that "In absence of the railroad (power) load, it does not look like (West Creek) is feasible." [78]

The West Creek project was effectively abandoned at that point. Studies generated by the project, however, were completed long afterward. In March 1983, Ertec Northwest completed its cultural resources survey of the project. That report revealed a host of significant archeological and historical sites in Dyea and on the ridge between the Taiya River and Long Bay. [79]

One of the major sites discovered during the Environaid and Ertec surveys was a marine shell midden located adjacent to Dyea Road, south of Dyea Campground. Investigators considered it sufficiently important to recommend it potentially eligible to the National Register of Historic Places. They filled out no form at that time. Late in 1984, however, the state's Department of Transportation and Public Facilities contemplated a series of widening projects along Dyea Road. Because such actions had the potential to impact the marine shell deposit, the agency contracted with Alaska Archives and Records Management, headed by Glenda Choate. Choate and Nan Fawthrop completed a National Register nomination for the "Dyea Shell Midden" in January 1985. [80]

Interpretive and Ranger Activities

As noted above, the 1973 master plan had called for relatively little park interpretation in the Dyea area. The interpretive centerpiece was to be a combination ranger station and interpretive center; in addition, the agency would interpret the two historic cemeteries, the wharf, and the old townsite. [81]

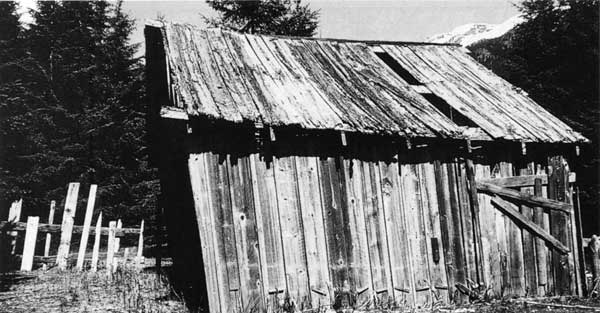

The plan was implemented slowly and spasmodically. The ranger station was built during the summer of 1979. The following year, rangers installed bulletin boards at Dyea campground and the Chilkoot Trailhead. In 1981, the park's Interpretive Prospectus proposed that a coordinated series of wayside exhibits be placed in Dyea and along the Chilkoot Trail. That plan, if implemented, would have resulted in the installation of historical markers along Dyea Road, at the Slide Cemetery, beside the Long Wharf pilings, and at the false front (the A. M. Gregg real estate office). The plan, however, was revised in 1983 because of cultural resource concerns, and for the time being, signs were installed at only the first two sites. To augment area signage, seasonal ranger Rosemary Libert, in 1984, created ad hoc interpretive markers at the Vining and Wilkes warehouse and the Pullen Barn, both of which had collapsed and were in danger of being looted for firewood. In the late 1980s, as noted in Chapter 9, the wayside exhibit package was completed and new signs were installed. [82]

The Dyea ranger station was an "interpretive center" in only a narrow sense. It offered few mounted photographs or display materials. It did, however, contain various brochures and booklets about the Chilkoot Trail, and its primary purpose was to inform hikers and potential hikers about the conditions that awaited them on the trip north.

In order to provide a broader scope of informational materials, park staff moved to establish a branch of the Alaska Natural History Association. The idea of establishing an independent cooperating association based in Skagway had been around for years, but pressure from local businesses had prevented its creation. It was not until 1981 that an ANHA branch was founded at the park. The branch, which operated only out of the Dyea Ranger Station, was overseen by the park's interpretive specialist. It sold books--both historical volumes and nature guides--and topographic maps. Sales totals were never large. Total revenues in 1981 were $270. Revenues rose to $285 in 1982 and to $353 in 1983. In 1984, only $119 in sales was recorded. Even that amount of sales, however, caused friction with local business owners, so at the request of the park's interpretive specialist, ANHA closed its Klondike branch. It did not reopen again until the spring of 1996, when an outlet opened in the visitor center. The branch sold books, maps, and the Chilkoot Trail hikers' guide. [83]

Because of the closure of the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad in October 1982, tour companies were eager to find tour destinations to replace the popular rail trips to Fraser and Bennett, B.C. In their search for an alternative tour destination, they found Dyea attractive, both for its scenic and historical resources. Beginning in 1983, therefore, Dyea began to attract a significant number of bus tours. Alaska Sightseeing Company patrons rode out Dyea Road to the Chilkoot Trail head, walked a few yards up the trail, and received a hiker's certificate for their efforts. They then rode to and ambled around the Slide Cemetery before heading south to the wharf pilings and the collapsed warehouse. Typically, the bus tours stopped here for a snack. NPS rangers often met the buses and gave a ten minute historical talk to the assembled patrons. Tours such as this remained popular through 1984. [84]

In 1985, the Dyea area hosted a new set of tour possibilities. Skagway business persons Duff and Carla Ray organized the Chilkoot Trail Float Tours, which offered float trips along the Taiya River from the West Creek confluence to the Dyea flats. That tour lasted for only one season. Alaska Sightseeing's new tour, however, proved more permanent. The company shifted its operations from the Dyea townsite to a makeshift tent camp adjacent to the McDermott cabin, where visitors were given the opportunity to pan for gold. Bus tours to the gold camp continued until the late summer of 1987. The following year, the restoration of train service truncated interest in the Dyea area, and organized tour groups did not return to the Dyea townsite until the mid-1990s. [85]

As the above paragraphs have suggested, rangers during this period pursued a variety of activities while stationed at Dyea. As a rule of thumb, rangers spent several days of their job rotation living at Sheep Camp and working along the Chilkoot Trail. Before or after their trail stint, they lived in Dyea and worked on a variety of assignments. Typical jobs included patrolling the park roads and the park boundary lines, answering inquiries, and responding to search and rescue, accident, or other emergency situations. [86]

Revising the Cooperative Agreement

In April 1978, the NPS and the state's Department of Natural Resources had signed a cooperative agreement that affected activities in Dyea, on the Chilkoot Trail, and in the White Pass Unit. That agreement should have been renewed in April 1981. The two parties, however, were unable to come to terms at that time, so they signed an interim agreement that terminated "at such time as a more comprehensive agreement is consummated or April 6, 1982, whichever comes first." That agreement was extended for another 45 days. Then, in May 1983, state and federal officials signed another extension that continued the agreement until the end of the year. [87]

It is not clear why the two parties could not agree on an updated cooperative agreement. The state, for its part, replaced its state park directors several times during this period, making progress difficult, and NPS management found it frustrating that conclusions reached in its meetings with state parks personnel were rebuffed by higher-ups in DNR. The NPS, for its part, was unhappy with having to manage the state's Chilkoot Trail Unit lands. It attempted, therefore, to exert whatever leverage it could in order to acquire fee simple ownership.

NPS officials made no secret of their desire to acquire the state's lands in the park, and in order to ease the process, they appealed to Congress for a new acquisition method. Section 1(b)(1) of the 1976 park authorization act had specified that the NPS could acquire state lands in the Chilkoot Trail Unit only by donation. But by December 1977, the Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus had suggested to Governor Jay Hammond that exchange become an additional transfer mechanism. The suggestion, which was apparently uncontroversial, was quickly forwarded to the Congressional delegation, and by 1979 an identical provision had been included in the committee bills of both the House and Senate versions of the Alaska Lands Act. The provision remained in the final bill passed by both houses, and it became Section 1309 in the Alaska Lands Act signed by President Jimmy Carter in December 1980. [88]

Given the new regulation, NPS officials requested the state to select other federal lands which would be acceptable for exchange purposes. DNR officials, however, were satisfied with the existing situation in the Chilkoot Trail Unit. They liked the idea of having another agency expend the funds to manage the state's lands; because of their ownership position, they liked being able to influence NPS policy regarding trail-related matters. But they had no interest in managing it again. As State Parks Director Neil Johannsen said, "The only way the state could come back in here would be at tremendous state expense. Years ago we managed the trail and we did not do as good a job as the NPS has done on the trail." [89] And they were equally reluctant to transfer their land to the NPS, so they dragged their feet in the selection of appropriate federal exchange lands. This conflicting state of affairs, as noted above, was partially responsible for the numerous delays and interim agreements that took place during the early 1980s.

In early 1983, as noted above, state and federal officials had signed an extension of the cooperative agreement that kept it in force until the end of the calendar year. By the time that agreement expired, officials were well on the way toward formulating a new, comprehensive agreement, and on February 3, 1984, Natural Resources Commissioner Esther Wunnicke signed a Memorandum of Understanding governing the management of state lands within the park. NPS Regional Director Roger Contor signed the MOU eleven days later. The memorandum, to a large extent, was a repeat of the 1978 cooperative agreement; like the earlier agreement, it pertained to state lands in Dyea, along the Chilkoot Trail, and in the White Pass Unit. The most substantive change, insisted upon by the NPS, was that park rangers would be commissioned as state Natural Resources Officers and would be given the authority to enforce federal park regulations (known as 36 CFR regulations) on state lands in the park. The MOU was scheduled to be effective for five years. [90]

The new MOU was presented to Skagway residents at a public meeting in the NPS visitor center on April 27. Chief Ranger Jay Cable led the meeting and laid out the differences between the 1978 and 1984 federal-state agreements. Under the new regulations included in Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the following rules would pertain to state land in Dyea within the park: no woodcutting, no hunting, and no camping outside of designated areas (either in Dyea or on the trail), no firearms on the trail, and no commercial trips on the trail without a permit. Cable also voiced objections to horse grazing and model-airplane activity on the flats. But remembering the fiasco related to the 1980 land acquisition plan, he did not attempt to mandate the removal of either activity. He was also careful to note that the agency, in its implementation of these regulations, would not be stepping on any private property. [91]

Several days before the meeting began, the park staff learned from several local residents that the MOU would not be well received. Perhaps for that reason, Sims was away from Skagway that day, leaving Cable to be the designated meeting leader. As expected, the crowd of 75 lashed out at the NPS because residents wanted to continue such activities as woodcutting, hunting, snowmachining, model airplane flying, motorbike riding, fishing, grazing and even golfing. As the local press noted, "Rarely have Skagway residents been so vocal and united in their opposition to something." Most of their rancor, however, was vented not at the Park Service but at Linda Krueger and Carol Wilson of the state Department of Natural Resources, who had negotiated the agreement without a public hearing. Both were present, and "were in for an earful" from those in attendance. They admitted their mistake, with Wilson telling the crowd that "it was unfortunate that we did not know your concern." Most of those who commented said, in effect, that they liked the NPS so long as its role was limited to the preservation of gold rush history and the attraction of tourists. They railed, however, at any attempt the agency made to impinge upon the lifestyle of local residents. [92]

Peter Goll, who represented Skagway in the Alaska House of Representatives, had been warned earlier, by several constituents, that the MOU had been signed without a public process. He therefore attended the April 27 meeting, and afterwards he attempted to work out a compromise. He first spoke to city officials about their concerns; he then spoke to a meeting of the Citizens Advisory Commission on Federal Areas, the body that had been created in 1981 in the wake of the Alaska Lands Act (see above). The commission forwarded its comments to state Department of Natural Resources personnel, who attended a May 4 meeting with Skagway officials. Goll also informed Governor William Sheffield, the Congressional delegation, and NPS officials in Washington about the problem. [93]