|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hard Drive to the Klondike Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush |

|

CHAPTER SIX

Historic Resources in the Modern Era

"Today we need not regret that the commercial center moved on, leaving the area to stagnate. This lack of interest and investment insured that a remarkable stand of urbanistically compatible buildings from the end of the nineteenth century would remain. Streetscapes like that from Pioneer Square south along First Avenue are rare in a modern metropolis forced to reuse the same downtown area over and over."- Sally Woodbridge and Roger Montgomery,

A Guide to Architecture in Washington State, 1980

Pioneer Square: Seattle's First Commercial District

When the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1897, the area now called "Pioneer Square" was a thriving commercial district. A variety of businesses served the stampeders, including outfitting, hardware, and grocery stores. Today, most of Seattle's historic resources associated with the Klondike Gold Rush are located within this commercial district, extending from Columbia Street south to King Street and from Third Avenue west to Alaskan Way S. In 1970, this 52-acre area was listed in the National Register of Historic Places (National Register). In 1978, the boundaries of the district were expanded to 88 acres, and an additional three acres along the district's southwest end were added in 1987. [1] The district's three National Register nominations are included in the Appendix. After Pioneer Square was listed in the National Register, the City of Seattle established its own preservation district to facilitate management at the local level.

Buildings within the Pioneer Square Historic District date from three periods between the years 1889-1916. The first period, lasting from 1889 to 1899, represents the city's redevelopment after the fire. In the following period, which lasted from 1900 to 1910, Pioneer Square experienced tremendous growth and underwent significant development projects including regrading and filling in the tide flats. Just prior to World War I, the district experienced a final surge of construction. [2] After the war, Seattle's retail district moved north of Pioneer Square along First and Second avenues.

Pioneer Square Historic District

The Pioneer Square Historic Distrcit Boundaries.

(Pioneer Square National Registration Nomination, 1987)

The City of Seattle's Pioneer Square Preservation District Boundaries.

(Courtesy Office of Urban Conservation, Seattle)

Over the years, this shift resulted in the abandonment of Pioneer Square. Buildings in Pioneer Square that once hummed with commercial activity were left vacant or used for storage.

In 1966, an "urban renewal" project proposed by a local planning group known as the Central Association threatened the area. Under the Central Association's plan, buildings in Pioneer Square would have been replaced by modern parking garages. [3] However, as architectural historians Sally Woodbridge and Roger Montgomery explained, "streetscapes like that from Pioneer Square south along First Avenue are rare in a modern metropolis forced to reuse the same downtown area over and over." [4] Recognizing the importance of this intact historic district, preservationists, led by the non-profit Allied Arts of Seattle, worked to raise awareness of Pioneer Square's historic and architectural significance. As a result of these efforts, Pioneer Square became the city's first National Register district in 1970. [5] Historic designation revitalized Pioneer Square by attracting the attention of private developers interested in rehabilitating buildings; businesses seeking commercial space; and individuals interested in the area's stores and colorful history.

In 1976, as Pioneer Square regained its foothold as an important commercial center, Congress established the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, which included a Seattle Unit, in the district. A copy of the statute that created the Park is included in the Appendix. Today, the Park's interpretive exhibits and tours of Pioneer Square allow visitors to envision Seattle during the gold-rush years of the late 1890s.

Seattle's Gold-Rush Era Properties Located Outside the Pioneer Square Historic District

Although most buildings associated with the gold rush in Seattle are located within the Pioneer Square Historic District, some properties lie outside the district's boundaries. This study involved the identification of gold-rush era resources that are located outside the district and which date from after the Seattle fire in 1889 until the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYP) in 1909. Seattle expanded rapidly during this period, in part due to the influx of miners and mining-related businesses. The study also includes properties associated with the AYP because it represents the culmination of Seattle's fascination with the Far North. The already familiar AYP properties located at the original fairgrounds on the University of Washington campus, however, have not been included in this study.

Historical Research Associates, Inc. (HRA) initiated the research for this project by contacting historical preservation agencies and organizations to inquire about their knowledge of gold rush resources located outside the Pioneer Square Historic District. Those contacted include the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Seattle Office of Urban Conservation, Allied Arts, and Historic Seattle Preservation and Development Authority. The latter assisted in identifying the house of George Carmack, who filed the first claim for Klondike gold.

HRA historians obtained the addresses of additional properties through research in Seattle City Directories. Using key words such as "Alaska, Klondike, Miner, and Yukon," HRA identified addresses of businesses located outside the Pioneer Square Historic District. A similar process was used to go through Klondike guidebooks, which advertised businesses associated with the gold rush. The National Park Service (NPS) is currently developing a database, which includes scanned gold-rush images from historic newspaper articles, advertisements, and photographs. HRA used the database to help identify the addresses of gold rush businesses.

HRA also used Seattle City Directories to determine the addresses of individuals who played an important role in the gold rush. HRA researched the residences of Seattle promoter Erastus Brainerd, Mayor William Wood, and miners Tom Lippy and George Carmack. Information relating to the architectural characteristics and history of the Wood and Carmack residences is included later in this chapter. HRA determined that the Brainerd and Lippy homes had been demolished. During the early 1900s, Brainerd lived in downtown Seattle at 1116 Fifth Avenue and in 1909 he moved to Richmond Beach. The YMCA building replaced Brainerd's downtown address in 1913. [6] From 1900 until 1931, Thomas Lippy lived in a grand house located at 1019 James Street. Constructed by Seattle Pioneer James Scurry in 1890, the house was demolished in 1966. [7]

HRA conducted further research on identified buildings by looking at their specific addresses in Sanborn Fire Insurance maps and obtaining King County Assessor's historic property cards for each building. Historians obtained information about the historic use of some properties by accessing articles and advertisements listed in the NPS database of gold mining businesses. HRA obtained available records associated with the early history of buildings from the Seattle Department of Construction and Land Use. HRA also consulted historic preservation records filed at the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation and Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. These records included National Register and City landmark nominations.

The nine gold-rush era buildings that HRA identified outside the Pioneer Square Historic District include the U.S. Assay Office (613 9th Avenue), the Colman Building (801-821 First Avenue), the Grand Pacific Hotel (1117 First Avenue), the Holyoke Building (1018 First Avenue), the Globe Building (1007 First Avenue), the Moore Theatre and Hotel (1932 Second Avenue), the George Carmack House (1522 East Jefferson Street), the William Wood House (816 35th Avenue) and the Woodson Apartments (1820 24th Street). Six of these buildings are listed in the National Register and as Seattle Landmarks. The nomination for each National Register property is included in the Appendix. The unlisted Carmack and Wood houses appear eligible for the National Register. Although the Woodson Apartment building possesses an association with the AYP as an example of residential development that occurred prior to the event, physical alterations have compromised its integrity making it ineligible for the National Register. A catalog at the end of this section provides current and historic photographs, along with a summary of each property's architectural characteristics, past uses, and potential eligibility for the National Register.

While the Pioneer Square Historic District's gold rush resources are located within a cohesive group of properties built soon after Seattle's 1889 fire, most of the buildings identified outside the district were constructed later. Six of the properties outside Pioneer Square are associated with two phases of development: the northward expansion of downtown along First Avenue (1889-1909) and Seattle's preparation for the AYP (1907-1909). The development of a commercial district along First Avenue began as early as 1889 with the construction of the Holyoke Building at the southeast corner of First Avenue and Spring Street. [8] It was not until the turn of the century, however, that a considerable amount of development occurred in this area. Construction associated with the AYP was limited to the years just prior to the event. Three properties, notably the U.S. Assay Office and the houses of George Carmack and William Wood, do not correspond to the above listed phases.

HRA determined that the Holyoke Building, the Grand Pacific Hotel, the Globe Building, and the Colman Building are associated with both the northward expansion of Seattle's retail district and the gold rush. During the 1970s, the Seattle Office of Urban

Conservation recognized the historic significance of buildings along First Avenue and worked to establish a First Avenue Historic District stretching from Pioneer Square (Columbia Street) north to the Pike Place Market (Union Street). The Office of Urban Conservation determined after numerous public hearings and the demolition of an entire block of these buildings that the historic First Avenue properties should be nominated individually rather than as a district. Several of the historic First Avenue properties, including the Holyoke and the Colman buildings, had already been listed in the National Register. Consequently, in 1980, the Office of Urban Conservation prepared a National Register nomination for the following seven buildings, referring to them as the First Avenue Groups: the Globe Building (1001-1011 First Avenue), the Beebe Building (1013 First Avenue), the Cecil Hotel (1019-1023 First Avenue), the Coleman Building (94-96 Spring Street), the Grand Pacific Hotel (1115-1117 First Avenue), the Colonial Hotel (1119-1123 First Avenue), and the National Building (1006-1024 Western Avenue). The Coleman Building is the only property from this group that was not listed in the National Register. A copy of the First Avenue Groups' National Register nomination is included in the Appendix.

According to the First Avenue Groups' National Register nomination, the Grand Pacific Hotel, the Globe Building, the Beebe Building, the Cecil Hotel, and the Colonial Hotel were constructed to house Seattle's large transient labor population, which had grown as a result of the Klondike Gold Rush. [9] Research indicated the Grand Pacific Hotel and the Globe Building also housed businesses associated with the gold rush. The Seattle Woolen Mill, which outfitted miners with clothing and blankets, was located in the street-level commercial space of the Grand Pacific Hotel from 1899 until 1914. From 1903 until 1912, the Globe Building housed the offices of the Alaska Gold Standard Mining Co., and from 1908 until 1909 the Treasurer's Office for the AYP was also located in the Globe Building. [10] Because HRA did not find additional information connecting the gold rush and the Beebe, Cecil, and Colonial hotels, these buildings were not included in the catalog.

The Holyoke Building, located at the southeast corner of Spring Street and First Avenue, is also part of the commercial district's northward expansion. In 1976, the Office of Urban Conservation nominated the Holyoke Building as a fine example of the Victorian Style. The nomination also noted that the Holyoke was the "first office building to be completed after

Seattle's disastrous fire of 1889." [11] HRA determined that during the gold rush the Northwest Fixture Company, a supplier of lighting equipment for Klondike miners, occupied the Holyoke from 1894 until 1900. [12]

Advertisement for Rochester Clothing Co., 1897, located in

the Colman Building at 805 First Avenue.

The Colman Building, located on the west side of First Avenue between Columbia and Marion streets, was constructed in 1889 as Seattle's commercial district spread northward. Architect Stephen Meany originally designed the Colman Building as a two-story Romanesque Revival building. In 1904, architect August Tidemand redesigned it into a six-story Chicago Style building. [13] It has been listed in the National Register as a fine example of the Chicago Style of architecture and for its association with James Colman an influential businessman in Seattle. [14] The Colman Building housed two businesses that catered to gold seekers. The grocer Louch, Augustine & Co. occupied the Colman Building from 1894 until 1907, and the Klondike clothing outfitter, Rochester Clothing Co. was located in the building from 1897 until 1899. HRA also determined that during the AYP years, the Colman Building housed the offices of the exposition's publisher and legal counsel. [15]

The Moore Theatre and Hotel and the Woodson Apartments were constructed in direct response to the AYP. Anticipating the event, land developer James A. Moore constructed his namesake Theatre and Hotel in downtown Seattle. When the theatre opened on December 28, 1907, its connection to the AYP was stressed by featuring a comic opera entitled The Alaskan. [16] The Moore is listed in the National Register because of its unique design, association with the AYP, and its role as a "leading cultural house in the city." [17]

Expecting an increased need for housing due to the AYP, Irene and Zacharais Woodson constructed the Woodson Apartments in the Central District. Although the Woodson Apartment building possesses an important tie to the AYP, it is not eligible for the National Register because physical changes have compromised its integrity.

The U.S. Assay Office and the houses of miner George Carmack and Mayor William Wood are not associated with either the commercial district's northward expansion along First Avenue or the AYP. Among the properties included in this study, the U.S. Assay Office is the most directly related to the gold rush. Although it was not originally constructed as an assay office, public demand for a federal assayist required that this entertainment hall be converted for government use as an assay office in 1897. According to this property's 1969 National Register nomination, it continued to be used for this purpose until 1932. [18]

When George Carmack first returned from the Far North, he lived in hotels in the Pioneer Square area. From 1905 until 1909, he lived in a house at 3007 East Denny, which no longer remains standing. [19] The house Carmack lived in from 1910 until his death in 1922 is still standing in Seattle's Central District. This property appears eligible for the National Register for its association with Carmack, who filed the first claim for Klondike gold.

As the mayor who left his post to try his hand at mining in the Yukon, William Wood played a significant role in Seattle's gold rush history. Prior to the gold rush Wood owned a large amount of land east of Greenlake, which he was responsible for platting. According to Seattle City Directories, from 1892 until 1900 he lived at the intersection of Woodlawn and Greenlake. Because historical maps do not show that Woodlawn and Greenlake intersect, HRA could not identify the location of Wood's house during this period. Between 1900 and 1904, Wood lived at two different addresses and from 1905 until 1915, he lived at 816 35th Avenue. [20] The latter property appears to be eligible for the National Register because of its association with him.

The following catalog includes the six National Register-listed and three unlisted properties that HRA identified as associated with the Klondike Gold Rush. For each building, the catalog includes a description of the property's design and its association with the Klondike Gold Rush. The map shows the location of each property.

Seattle's Gold-Rush Era Properties Located Outside

the Pioneer Square Historic District

Properties Associated with the Gold Rush Located Outside the

Pioneer Square Historic District.

U.S. Assay Office

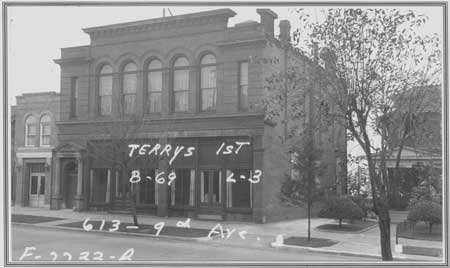

| Property 1 | U.S. Assay Office 613 Ninth Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No.: 859040-0796 Legal Description: Lot 3, Blk. 69, Terry's First Add. National Register Status: Listed on March 16, 1972 |

Architectural Description

The two-story U.S. Assay Office is an "excellent example of a 19th century commercial cast-iron and masonry building, typified with larger, open street level bays and narrow vertical window openings on other facades and on the upper street-front level." [21] The front facade includes two traditional style storefronts consisting of large windows, kick plates, and transoms. The arched entrance to the second floor space is surrounded by columns and a pediment. Five centrally located arched windows on the second floor are flanked by narrow rectangular windows. The protruding central portion of the parapet wall is decorated with a wooden cornice and brackets.

The U.S. Assay Office has undergone several minor alterations, including a narrow addition featuring arched windows similar to rest of the building added to the south side of the building. Many of the building's windows have been replaced or filled-in. Two first-floor windows on the north side of the building have been filled with brick. One south side window and all the second story windows on the rear (west) of the building have been replaced. A small wood sided addition has been added to the southwest corner of the building's second floor.

Historical Significance

The building that housed the U.S. Assay Office was erected in 1886 by Thomas Prosch, a secretary of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and owner of the Post-Intelligencer, for use as an entertainment hall and office building. Originally, the first floor was used as offices and the second floor was rented as a ballroom. During the gold rush, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce recognized the city's need for a federal assay office. The Chamber of Commerce, represented by Erastus Brainerd, successfully lobbied for the establishment of an assay office. In May of 1898, the federal government rented Prosch's building and on July 15, 1898, the U.S. Assay Office opened. The Assay Office included a melting department. During the early years of the Klondike Gold Rush, deposits in the office reached approximately $20 million. In 1932, the U. S. Assay Office moved to a government-owned building.

In 1935, the Deutsches Haus (German House) purchased this property and renovated it for use as a social center. During World War II it was used as an entertainment center. After the war, the Deutsches Haus again occupied the structure. [22] The building is currently owned by the German Heritage Society.

The U.S. Assay Office is historically significant as a fine example of commercial cast-iron and masonry architecture, and because of its association with the Klondike Gold Rush, an event that contributed to the economic growth of Seattle. [23]

U.S. Assay Office's east facade, 1998.

(HRA photo)

Historical photograph of the U.S. Assay Office, circa 1937.

(Courtesy Washington State Archives, Puget Sound Regional Branch)

Colman Building

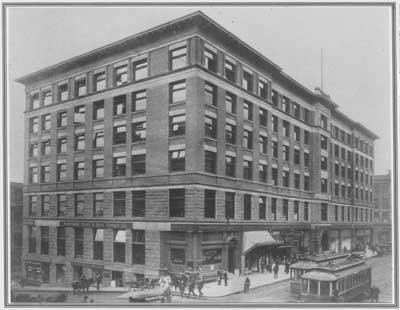

| Property 2 | Colman Building 801-821 First Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No.: 859140 0005 Legal Description: Lot 2 & 3, Blk. 1, Terry's Third Add. National Register Status: Listed on March 16, 1972 |

Architectural Description

The six-story Chicago Style Colman Building occupies the east half of the block located on the west side of First Avenue between Columbia Street and Marion Street. In a Seattle Landmark nomination form, the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation described the Colman Building as follows:

The Colman Building is a six-story concrete and brick office building with stone and marble trim that epitomizes the Chicago Style and its influence upon Seattle architecture.... The exterior of the lower floors was faced with rusticated stone and the additional floors with red brick. A central bay which, at the First Avenue ground level houses the main entrance to the building, protrudes from the rest of the facade and is faced in the same stone as the lower floors. On either side of this central section, the building facade is divided into four equal sections consisting of five structural piers and four window spandrels each. The outermost corner sections extend outward slightly from the adjacent sections, providing a subtle undulation of the surface. A narrow banding just below the top floor and a modestly extended copper cornice crown the building.... The ground level retail shops were embellished by small multi-paned transoms and pediment and column entrances. The building is also distinguished by a metal and glass awning, which stretches along the entire east or front facade. [24]

Historical Significance

The original two-story Colman Building was erected by James Colman, an influential businessman who arrived in Seattle in 1861. Colman's entrepreneurial tendencies involved him in a variety of businesses, including owning woolen mills, land acquisition, and railroading. Colman was one of the major promoters of the railroad to the Renton Coal mines. He operated this railroad for one year until Henry Villard of the Northern Pacific Railroad took it over. [25]

In 1890, the two-story Colman Building was constructed on the site of the old Colman Block, a wooden building that burned in the fire of 1889. The Colman Block had been built on the remains of the ship Winward, which had wrecked near Whidbey Island. Intending to salvage the boat, James Colman bought it and towed it to his dock in Seattle. When the Colman Block was constructed the ship was surrounded by land and buried under the foundation of the Colman Block. [26]

Architect Stephen Meany originally designed the Colman Building as two-story Romanesque Revival structure. In 1904, the Danish architect August Tidemand remodeled it into Seattle's "earliest example of the Chicago Style of commercial architecture." [27] All that was retained of the original facade were the cast iron columns between the storefront bays on First Avenue. The Colman Building has been recognized as historically important for its architectural style and association with James Colman. [28]

The Colman Building housed two businesses that catered to gold seekers. The grocer Louch, Augustine & Co. occupied the Colman Building from 1894 until 1907 and the Klondike clothing outfitter, Rochester Clothing Co. was located in the building from 1897 until 1899. HRA also determined that from 1908 until 1909, the Colman Building housed the offices of the AYP's publisher and legal counsel. [29]

Colman Building, 1998.

(HRA photo)

Colman Building prior to 1904.

(Courtesy Seattle Office of Urban Conservation)

Colman Building, circa early twentieth century.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

Grand Pacific Hotel

| Property 3 | Grand Pacific Hotel 1117 First Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No.: 197460-0050 Legal Description: Lot 3, Blk. C, AA Denny's First Add. National Register Status: Listed on May 13, 1982 |

Architectural Description

The Grand Pacific Hotel is part of a collection of turn-of-the-century commercial buildings north of Pioneer Square on First Avenue. In 1980, the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation prepared a National Register nomination for this cluster of buildings referred to as the First Avenue Groups. The Seattle Office of Urban Conservation described the Grand Pacific Hotel in the following way:

The former Grand Pacific Hotel exemplifies the Richardsonian Romanesque Style in the composition and detailing of its primary or First Avenue elevation. Beginning at the ground floor, the elevation incorporates a bold central entrance arch flanked by clerestoried storefronts. The arch is constructed of lightly rusticated limestone blocks and voussoirs, as are the two stone block piers at the extreme ends of the store front zone.... Above the store front area and the archway, the First Avenue facade is dominated by a rhythmic two story arcade composed of nine square-based brick piers and eight round, cut stone arches which spring from elegant and compact stone capitals. Deeply recessed between these piers, the second and third story windows are separated by slightly recessed spandrels, faced in small, square, rusticated blocks. The fourth story of the First Avenue facade begins above a stone dentil course and consists of eight rectangular windows framed between short piers aligned with those of the arcade below. A parapet wall rising above the fourth story is detailed with recessed panels and a corbelled cornice. [30]

The First Avenue Groups' nomination noted that the hotel's storefronts suffered from uncomplimentary signage and a boarded-up central building entrance. Although the original storefront windows have been replaced in recent years, the new windows are well suited for the building. The building's main arched entrance is currently in use.

Historical Significance

Although the architect for the Grand Pacific Hotel is undetermined, this building has been recognized as "one of Seattle's finest examples of Richardsonian Romanesque commercial architecture." It has also been identified as one of "the last major buildings in Seattle to be designed in this style." [31] Circa 1898, the Grand Pacific Hotel opened under the name "First Avenue Hotel." This hotel, along with others included in the First Avenue Groups, was constructed in part to cater to the needs of Seattle's growing transient laborer population. Growth resulting from the Klondike Gold Rush resulted in an "acute need for new structures to provide necessary retail outlets and hotels for the large number of transients, dock workers, lumber workers and ship's crews." [32] The Grand Pacific Hotel filled the growing need for both housing and commercial space.

From 1899 until 1914, the Grand Pacific Hotel also housed the office and salesroom for the Seattle Woolen Mill, an important outfitter for the Klondike. According to Seattle City Directories, this company moved its offices from a neighboring building at 1119 First Street. This earlier building was replaced by the Colonial Hotel in 1901. [33] During the gold rush, the Seattle Woolen Mill advertised "Llama underwear, heavy Mackinaw clothing and double woven blankets for the Arctic Regions" as well as, "Blanket Clothing for the Klondike." [34]

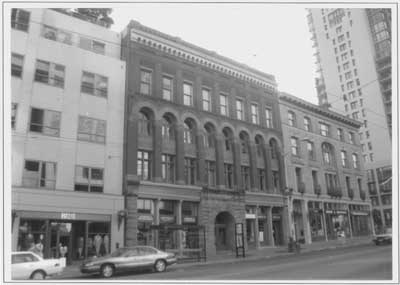

Grand Pacific Hotel, 1998.

(HRA photo)

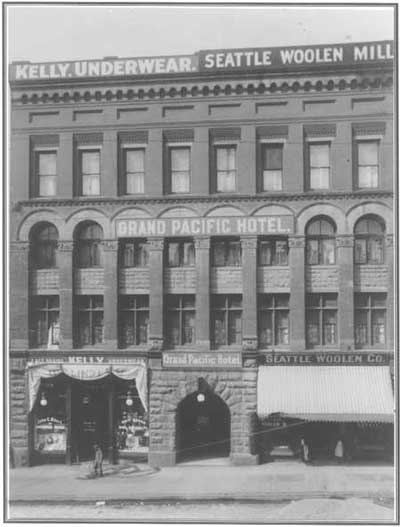

Grand Pacific Hotel, circa 1900.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

At the turn of the century, a banner across the top

of the Grand Pacific Hotel

advertised the Seattle Woolen Mill's office

and salesroom,

located at the building's street-level.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington,

Neg. No. Curtis2302)

Holyoke Building

| Property 4 | Holyoke Building 1018 First Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No.: 093900-0515 Legal Description: Lot 1, Blk. 12, Boren/Denny Add. National Register Status: Listed on June 3, 1976 |

Architectural Description

The five-story Holyoke Building is essentially Victorian in style. The building's emphasis on verticality evidenced in the tall narrow windows and closely spaced repeating piers is characteristic of Victorian buildings. It was framed with post and beam construction and clad in red brick. A continuous band of concrete runs across the top of the building and is repeated on the upper-stories in the form of interrupted concrete bands above each of the windows. These details off-set the strong vertical emphasis by providing distinct horizontal lines.

Concrete detailing compliments the gray-colored rusticated stone block first-floor facade. The Holyoke Building's principal facade faces First Avenue. Because the building is set into the hillside formed by Seneca Street, the stonework along this secondary street-facing facade is cut-off by the incline. The Holyoke Building's commercial store-fronts, complete with recessed doorways, kick plates, and large store-front windows are still intact. Few alterations have been made to the original design of this building.

Historical Significance

In 1890, lumberman Richard Holyoke constructed the Holyoke Building. Architects Thomas Bird and George Dornbach had planned the construction of the Holyoke Building prior to Seattle's 1889 fire. After the fire had occurred, the Holyoke Building was one of the first office buildings to be completed. [35]

This building represents the northward expansion of Seattle's downtown spreading out from Pioneer Square. In the late 1890s, the Klondike Gold Rush caused increased development activity resulting in the construction of hotels and commercial properties near the Holyoke Building. [36] During the gold rush, the Holyoke Building housed the Northwest Fixture Co. This company outfitted miners with electric motors and generators for mining and lighting. [37] This business was located in the Holyoke Building from 1894 until 1900. In the following years, the Northwest Fixture Co. moved to 313 First Avenue, where it was located until 1902. According to Seattle City Directories, it no longer existed after 1902. [38]

Holyoke Building, 1998.

(HRA photo)

Holyoke Building, circa 1900

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

Globe Building

| Property 5 | Globe Building 1007 First Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No.: 197460-0035 Legal Description: Lot 6 and 7, Blk. B, AA Denny's First Add. National Register Status: Listed on April 29, 1982 |

Architectural Description

The Globe Building is part of a collection of turn-of-the-century commercial buildings located just north of Pioneer Square and referred to as the First Avenue Groups. In 1980, the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation prepared a National Register nomination for the First Avenue Groups which provided the following physical description of the Globe Building's street-facing elevations:

The First Avenue facade is organized into three vertically ascending layers consisting of a continuous ground floor storefront zone, a two story body and an arcaded upper story. The storefront zone consists of large display windows and clerestories, many of which have been cosmetically altered with garish signage and other reversible accretions. Masonry walls above the storefronts are supported by a series of slender iron columns and horizontal girders encased within a terra cotta entablature. The walls are faced in tan-colored press brick and are penetrated by pairs of double hung windows at the second and third stories, and a nearly continuous arcade of round arched windows at the fourth story. Neo-classical detailing executed in ivory-colored terra cotta includes corner quoins, bracketed lintels above the second story windows, segmented flat arches above the third story windows and a terminating cornice detailed with an egg and dart motif. An arched entrance canopy, four iron balconies and a small roofline pediment originally incorporated at the center of the First Avenue facade no longer remain.

The Madison Street facade incorporates similar fenestration and detailing. The wall plane of this facade is interrupted at the center where a slight recess occurs beneath an elliptical terra cotta arch. The recess appears to have originally opened into an internal light court, which has since been enclosed. The wall surface now contains unadorned double hung windows. Openings at the basement level of this facade relate to the Arlington Garage, which occupied the lower floors of the building several decades after the building's initial construction.

Historical Significance

The First Avenue Groups National Register nomination indicates that the Globe Building was "constructed for developer J. W. Clise in 1901, and was originally occupied by retail stores, offices, and presumably lodgings." [39] This nomination indicates that the Globe Building, along with the Grand Pacific Hotel, housed the influx of transient laborers that arrived with the gold rush.

Among the offices housed in the Globe Building were two businesses associated with ties to the Far North that Seattle established during the Klondike Gold Rush. From 1903 until 1912, the offices of the Alaska Gold Standard Mining Co. were located in the Globe Building. Seattle's fascination with the Far North culminated in 1909 with the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition. From 1908 until 1909, the Treasurer's Office for this noteworthy event was housed in the Globe Building. [40] Today, this building houses the Alexis Hotel.

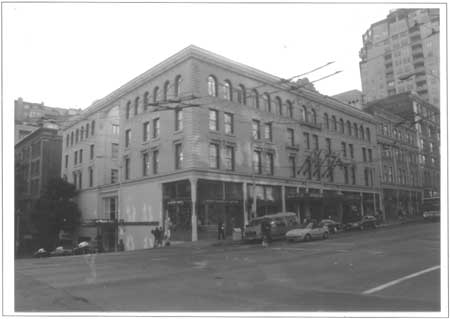

Northwest facade of the Globe Building, 1998.

(HRA photo)

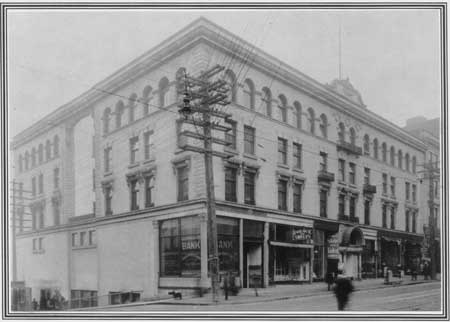

Globe Building, circa early twentieth century.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

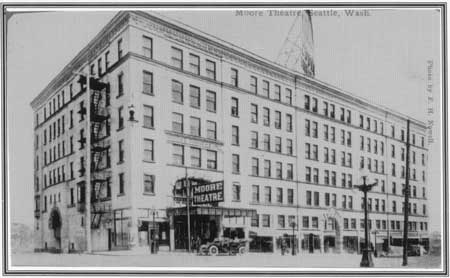

Moore Theatre and Hotel

| Property 6 | Moore Theatre and Hotel 1932 Second Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel Number: 197720-1035 Legal Description Lots 1,4,5, Blk. 46, Denny's 6th Add. National Register Status: Listed on August 30, 1974 |

Architectural Description

The seven-story Moore Theatre and Hotel building is located at the corner of Second Avenue and Virginia Street. The primary facade faces Second Avenue with another street-facing facade along Virginia. It is constructed of reinforced concrete with white glazed brick cladding. Accents of tan-colored terra-cotta appear over the main arched entrances, on the window sills, and on a panel which bears the name "Moore Theatre." These details along with a decorative cornice and freeze are the building's principal exterior embellishments.

In 1937, the building was reported to have 11 stores and 146 hotel rooms. [41] The building's commercial spaces along Second Avenue are still in use, although the original store fronts have been replaced with aluminum-framed windows and black siding. The theatre's original marquee has been replaced with a larger modern version. The windows throughout the building have been replaced.

Historical Significance

This building was constructed by James A. Moore, an early Seattle real estate developer who was responsible for erecting over 200 homes on Capitol Hill and platting Latona and part of what is now the University District. [42] In 1907, he opened the Moore Theatre and Hotel to accommodate anticipated crowds associated with the 1909 AYP. The building's design "was immediately noted nation-wide, and its use made it the leading cultural house of the city." [43] Moore Theatre and Hotel Architect E. W. Houghton designed a lavish interior which included onyx and marble in the theatre lobby and foyer.

The theatre opened on December 28, 1907, eight months after the hotel. James A. Moore had been convinced to open a theatre by the manager of the Northwestern Theatrical Association, James Cort. Cort became the manager of the Moore Theatre and attracted well-known entertainers to the theatre. Cort's successor Celia Schultz outdid him by regularly bringing a fantastic array of singers, dancers, and instrumentalists to the theatre until 1949 when she resigned. Until the 1950s, the Moore Theatre played a leading role in the Seattle entertainment industry. It continues to hold musical concerts today. The National Register Nomination for this building notes the following:

The Moore is significant not only for theatrical contributions, but also for its outstanding theatre architecture. From the expensive exterior construction, withstanding both climatic and earthquake stresses, to interior design features of exiting ramps, excellent sight lines, superior stage "life," and acoustics, the Moore is among the best example of theatre architecture and engineering ahead of its time, to be found in the country. [44]

The Moore Theatre and Hotel building was closely associated with the AYP. As noted, it was constructed in part to cater to AYP visitors. When the theatre opened, its first production was a comic opera entitled, The Alaskan. Journalist Jane Lotter explained that during that time period "Seattle was still in the midst of a love affair with the North that had begun with the 1897 gold rush and The Alaskan was a guaranteed crowd pleaser." As expected, the opening performance was a hit with 2,500 people- including the governor, the mayor, James A. Moore and John Cort-attending the performance.

Northeast corner of the Moore Theater and Hotel, 1998.

(HRA photo)

Historical postcard of the Moore Theater and Hotel, circa 1909.

(Courtesy Office of Urban Conservation, Seattle)

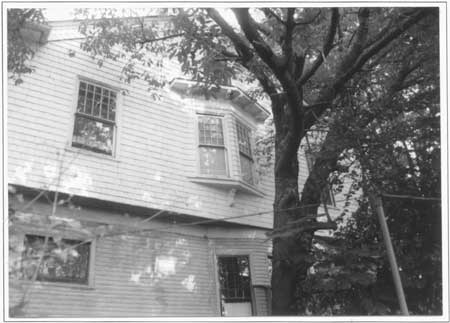

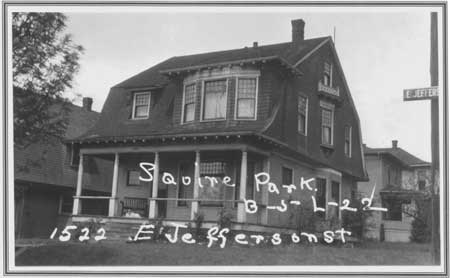

George Carmack House

| Property 7 | George Carmack House 1522 East Jefferson St. Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No. 794260-0795 Legal Description Lot 22, Blk. 5, Squire Park Add. National Register Status: Unlisted |

Architectural Description

The George Carmack (1910-1922) residence is located at the corner of East Jefferson and 16th Avenue. It is a two and a half-story Colonial Revival house with a rectangular plan and a side-gambrel roof. This wood frame building is clad with white-painted clapboards at the first floor and shingles above. Dense vegetation currently surrounds the property, making it difficult to view the house. The original porch, which stretches across the front of the house (facing East Jefferson), has been enclosed with corrugated plastic siding. On the second floor above the porch is a shed roof dormer with bay windows. At the first level on the 16th Avenue side of the house is a bay with three double-hung windows. Like most of the building's lights, these windows have multiple panes above and a single pane below. Another bay with two double-hung windows and a bracketed eve is located above the first-story bay. Over the years, this building has undergone few exterior alterations.

Historical Significance

George Washington Carmack, the "official discover of Klondike gold," lived in this house from 1910 until 1922. On August 16, 1897, Carmack discovered gold along Bonzana Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River. Carmack was married to a Tagish Indian woman named Kate. When he discovered the gold, he was accompanied by two Tagish men Skookum Jim Mason, and Dawson (Tagish) Charley. By filing a claim first, Carmack became credited with finding the Klondike lode. After Carmack arrived in Seattle on July 17, 1897, the stampede to the Klondike began. [45]

When Carmack and his wife disposed of their holdings in the Klondike, they moved to Seattle where they took residence at the prestigious Hotel Seattle. Kate Carmack did not enjoy living in Seattle and returned to her northern home. [46] Carmack soon thereafter married a woman named Marguerite. Carmack eventually left the Hotel Seattle, but continued residing in the Pioneer Square area. From 1905 until 1909, he lived in a house at 3007 East Denny Way, which has since been removed. By 1910, Carmack moved to 1522 East Jefferson. According to Seattle City Directories, Carmack lived at this address until he died in 1922. [47] Marguerite Carmack continued living in the house until the 1940s. A considerable amount of development has occurred around this house, which is still used as a residential structure.

East side of the George Carmack House, 1998.

(HRA photo)

George Carmack House, circa 1937.

(Courtesy Washington State Archives, Puget Sound Regional Branch)

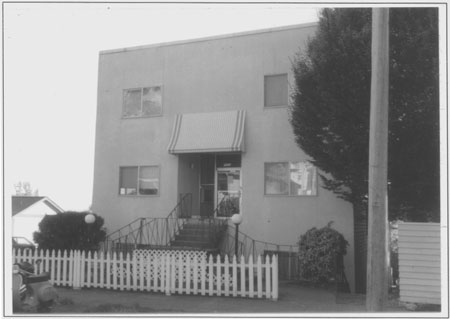

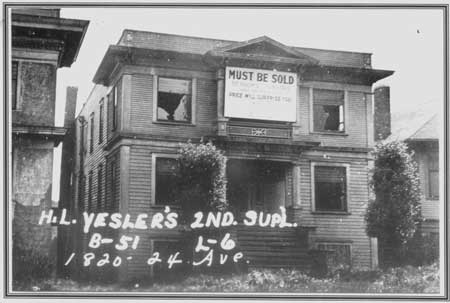

Woodson Apartments

| Property 8 | Woodson Apartments 1820 24th Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No. 982870-2660 Legal Description: Yesler's H. L. Second Addition Supplemental, Blk. 51, Lot 6 National Register Status: Unlisted |

Architectural Description

The Woodson Apartments, known today as the Cascade View Apartments, have undergone numerous alterations over the years. This two-story rectangular building is located on the east side of 24th Avenue and stretches from the street to an alley east of the property. The building originally had a two-story porch that protruded from the center of the east facade to shelter the main entrance on the first floor and a similar space at the second level. The second-story porch had a low-pitched gable roof supported by classical columns. The same style columns also supported the porch at the first level. A cornice once extended across the principle facade and around the building's north and south corners.

Today, the architectural details that once characterized the Woodson Apartments have been removed. The two-story porch has been replaced with a simple metal awning over the main entrance. A metal railing borders the concrete stairway leading to the entrance. The cornice has been removed and the original double hung windows have been replaced with aluminum frame versions. The east side of the building is covered in a composite concrete and the rest of the building is clad in vinyl.

Historical Significance

In 1908, Zacharias and Irene Woodson built this apartment anticipating that the AYP would increase the demand for housing in Seattle. According to Esther Mumford's Seattle's Black Victorians, the Woodsons came to Seattle in 1897 and operated rooming houses during the first three decades of the century. [48] Seattle City Directories list Zacharias as a "bootblack" in 1899. By 1903, however, Zacharias is listed as being the proprietor of a rooming house at 1216 Second Avenue In 1909, the Woodsons are listed as the proprietors of both the Woodson Apartments and a rooming house at 1530 Fifth Avenue. [49] This property represents the growth Seattle experienced due to the AYP.

Woodson Apartments (Cascade View Apartments), 1998.

(HRA photo)

Woodson Apartments, circa 1937.

(Courtesy Washington State Archives, Puget Sound Regional Branch)

William Wood House

| Property 9 | William Wood House 816 35th Avenue Seattle, WA |

Tax Parcel No. 918470-0715 Legal Description: Washington Heights, Blk. 7, Lot 14. National Register Status: Unlisted |

Architectural Description

This two-and-a-half story Classic Box house is located in Madrona, on the edge of a hill overlooking Lake Washington. The house is set back from 35th Avenue and is approached by an alley-like driveway that runs between two houses set closer to the street. The east facing principal facade overlooks Lake Washington.

The house has a hip roof with hip-roof dormers on the east and west elevations. The exposed rafter tails that once decorated the eaves have been removed. The clapboard walls of the second floor flare slightly before meeting a flat board that separates the first and second floors. The northeast corner of the house has an inset porch supported by classical columns. The railing surrounding the porch has turned balusters. Most of the house's original windows are one-over-one and double hung. On the north side of the house is a ribbon of three leaded glass windows. The principle facade has a one-story bay window on its north side. The north, south, and west sides of the house are unaltered. The south elevation is obscured by thick vegetation making it difficult to discern if alterations have occurred to this side of the house.

Historical Significance

Seattle City Directories indicate that Seattle Mayor William Wood and his wife Emma lived in this house from 1905 until 1915. Wood had many interests which included working as a realtor, lawyer, and businessman. As a realtor in 1888, Wood owned a large amount of land on the east side of Greenlake, which he platted. Prior to becoming mayor in 1897, he acted as the president of W.D. Wood & Co. lawyers. His business interests included serving as president for both the Seattle-Yukon Transportation Co. and the Antimony Smelting & Refining Co.

The year the gold rush began, Wood became the Mayor of Seattle. Unable to resist the temptation of striking it rich, he, too, went to the Yukon for a short period. In the years following his return from the Far North, he lived in several different houses for short periods. It is unknown if Wood commissioned the construction of this house; however, it is likely that he and his wife were the first people to live here. [50]

William Wood House, 1998.

(HRA photo)

William Wood House, circa 1937.

(Courtesy Washington State Archives, Puget Sound Regional Branch)

Recommendations

Research

An examination of the papers of the Alaska Commercial Company and Northern Commercial Company could reveal much about the development of transportation facilities in Seattle. As noted in Chapter 3, historian Clarence B. Bagley observed that an increasing number of Seattle-owned shipping companies emerged during the early twentieth century. Further analysis of the records of the Alaska Commercial Company -- based in San Francisco -- could help explain this trend. Also, these documents could yield additional information about San Francisco's interest in the Klondike Gold Rush. They are located at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford Library in Palo Alto, California. Further research could be conducted to compile a more complete list of gold-rush era businesses, their activities, and their current status. The Appendix includes a list of such businesses compiled by the Centennial Committee of Washington State. To enhance this list, the names and locations of additional businesses may be obtained through turn-of-the-century newspapers (listed in the bibliography) and Seattle City Directories. To determine the current status of the companies, the Articles of Incorporation for each company could then be obtained from Secretary of State records at the Washington State Archives in Olympia. New information obtained from this research could be added to the NPS database and used for interpretive purposes.

Interpretation

In coordination with the City of Seattle, the NPS could develop signs to interpret historic buildings within the Pioneer Square area. The Pioneer Square Historic District has been chosen as one of Seattle's 37 urban villages, where intensive planning occurs to accommodate growth and commercial development that is neighborhood friendly. In March 1998, the City of Seattle released the "Draft Pioneer Square Neighborhood Plan." One of the top seven projects proposed in the Plan was to "facilitate strong coordination and partnering among projects to strengthen the neighborhood's unique historic character and arts identity." [51] The City proposed the development of a "comprehensive public art and history program" through the creation of legends and public art gateways. Utilizing information provided in this report and the NPS's database of gold-rush era businesses, the NPS could contribute valuable information to the interpretation of historic resources for use in public exhibits.

National Register Nominations

This project identified the house of George Carmack, the discoverer of the Klondike gold, and gold-rush era Mayor William Wood. Both houses appear eligible for the National Register under National Register criteria A and B, due to their association with the Klondike Gold Rush and significant individuals from that period. HRA recommends that a determination of eligibility for both properties be requested from the Washington Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. If the properties are determined eligible for the National Register, the property owner, the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation, and or a non-profit dedicated to historical preservation, could nominate both properties to the National Register, using the information provided in this historic resource study. Local historic preservation organizations that could nominate the properties include, Historic Seattle Preservation and Development Authority, Allied Arts, and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation.

The NPS, in collaboration with the Seattle Office of Urban Conservation, could consider conducting additional research on historic properties located within the Pioneer Square Historic District. Because National Register requirements have changed over the years, important historical and architectural descriptions are missing from the original 1969 nomination, which listed the majority of Seattle's oldest post-fire commercial architecture in the National Register.

Today, new National Register historic district nominations are required to provide detailed information about individual structures within a proposed district. Revising the Pioneer Square National Register nomination would provide an opportunity to both bring the nomination up to current standards and conduct research on the historic use of properties included in the original nomination. Such research is not necessary for the buildings included in the 1978 and 1987 amendments to the nomination, because individual descriptions of the historical use and architectural characteristics of these buildings were included in the boundary extension nominations. The new information could be consolidated into a document that would be a more useful planning tool for both the City and preservation organizations. Furthermore, historical research on the buildings included in the original district nomination would provide the NPS with valuable interpretive information about gold-rush era structures. Utilizing preservation and planning studies created since the designation of the historic district in 1969, the NPS could consolidate information about the current status of the district and its resources. The NPS database could provide information about the historic use of many of the district's buildings and new information obtained in the course of preparing the nomination could be added to the database. This new research material could enhance the Park's interpretive and educational programs, which present the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush to the public.

End of Chapter Six

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003