|

Lava Beds

Modoc War Its Military History & Topography |

|

Chapter 12

GILLEM'S CAMP

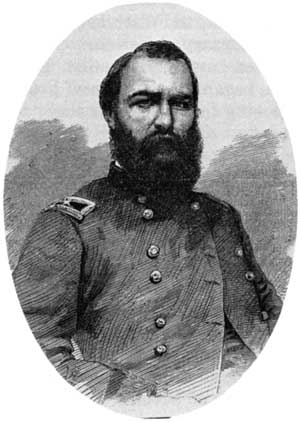

COLONEL ALVAN C. GILLEM

Special Report for a Self-guiding Trail

"When I first stood there, one bright day before sundown," wrote John Muir, "the lake was fairly blooming in purple light, and was so responsive to the sky in both calmness and color it seemed itself a sky." [1] The waters of the lake no longer brush the shore at Gillem's Camp. But to the viewer who today stands on the great bluff and looks down at the sea of lava and the distant shadows of the mountains, very little else has changed. If favored with imagination, one may readily visualize the teeming bivouc at the base of the bluffs that was Gillem's Camp for seven adventurous weeks in 1873. After the first battle of the Stronghold, in January 1873, Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton withdrew his command to Lost River, leaving the lava beds devoid of soldiers. Col. A. C. Gillem drew the line considerably closer when he moved his headquarters to Fairchild's, then to Van Brimmer's ranch in February. After early negotiations with the Modocs proved barren, Brig. Gen. E. R. S. Canby, now in the field, began his program of gradual compression, that is, moving the troops ever closer to the Stronghold with the intent of pressuring the Modocs into surrender.

As part of this policy, troops and pack trains left Van Brimmer's on April 1, marched eastward to the bluff, and scrambled down the narrow trail, which may still be identified today. Each man carried his own knapsack, haversack, blankets, and weapon. Mules eased their way to the small sward at the bottom, carrying the camp equipage and supplies and "before night everything was landed safely at the foot of the hill and camp established." [2]

It might have been called Canby's Camp, after the commanding general, or Green's Camp, after Maj. John Green who was in direct command of the troops on this, the west, side of the lava beds. However, Gillem, who was in charge of all the troops and of the campaign itself, contributed his name to the new establishment. Although he would experience a personal humiliation as a military commander at this new camp, his name would stick to the conglomeration of men, women, mules, horses, supplies, tents, and the history that this diversity made.

Top of Bluff

Slightly to the northwest of the camp the bluff reaches up to create a small knoll that is named on today's maps as Howitzer Point. The origins of this name are a mystery. While Keith Murray has questioned which particular area on the bluff should be called Howitzer Point, the answer is that the two mountain howitzers in Gillem's command were not emplaced on the bluff, neither were the mortars. [3] These two guns, received immediately before the first battle of the Stronghold, came to the lava beds on mules the day before that January battle, and they departed immediately afterwards with the defeated troops. They accompanied the troops to the camp at Lost River Ford. From there, Major Mason took them to the east side of the lava beds to his successive camp at Scorpion Point and Hospital Rock.

Mason employed these howitzers in his eastern attack during the second battle of the Stronghold, April 15-17. Immediately after occupying the Stronghold on April 17, the howitzers were placed in it so that their fire, if needed, could repulse the Modocs should they attack from their new positions from the south.

The Thomas patrol, April 26, had as its primary mission the task of determining whether the artillery could move into the lava beds to attack the Indians more directly. Whether or not the howitzers were moved from the Stronghold to Gillem's Camp at this time is unknown. If they were moved, there would be no reason to transport them all the way to the top of the bluff — Gillem's intentions were to move them into the lava beds, not away from them. It might be argued that Gillem moved the guns to the top of the bluff in the week of near-panic that followed the Thomas patrol and before Col. Jefferson Davis arrived on May 2. But there is no evidence to support this, and it is too much to be simply assumed.

It is equally unlikely that the four mortars, that were at Gillem's Camp, were placed on the bluff. The maximum range of these weapons was 1,200 yards, about three-quarters of a mile. From the bluff, their shells would have barely extended beyond the outer fringes of Gillem's Camp. More importantly, documentary evidence does not exist to support the contention that the mortars were taken up the bluff.

In 1961, the park personnel at Lava Beds conducted an interview with Kenneth McLeod, of pioneer stock and something of a history buff. In the course of the interview McLeod said he was certain that a hotel was situated on the bluff during the time Gillem's Camp was in operation. He believed it was a structure operated by the sutlers who had followed the army into the field, "This was their storehouse, warehouse, and also they took care of the visitors." He told the park staff that today one could see the remains "of a little main street of some sort." Although McLeod had run onto a source that there was a wooden building on the bluff at that time, he could not recall what the source was. [4]

Contrary to the mortars and howitzers, it is plausible that a hotel of sorts, canvas or wood, was erected on the bluffs. During the weeks the army occupied Gillem's Camp, hundreds of teamsters, camp followers, and others came eastward from Yreka on business or out of curiosity. It is possible that some entrepreneur did establish an overnight "hotel" on the bluff. But it must be added that no supporting documentary evidence has yet come to light.

Gillem's Camp

Gillem's Camp stood on an uneven swale located at the base of the steep, 400-600-foot bluff that overlooked the lava beds and Tule Lake. Paralleling the lake shore, running east and west, was the highest ground of the camp — a rise not quite high enough to be called a ridge. To the south of this rise was a considerable dip, low ground that would do for enlisted men's tents. Fingers of lava from the Devil's Homestead Flow marked out an uneven boundary on the east side, extending out into the lake to form a small unnamed peninsula that was the western border of Canby Bay. The water of the lake was shallow along the camp's shore. While it was suitable for both drinking and bathing, no evidence has come to light describing what arrangements were made to separate the two functions.

All the known facts that may be converted into symbols, such as troop dispositions, have been placed on the accompanying map of Gillem's Camp. There is in addition to that material certain historical evidence and interpretations that increase our understanding of the encampment.

One such source is the reminiscences of Peace Commissioner Meacham who recalled the first evening he spent in the new encampment, "Gen. Canby's tent was partly up when I passed near him. He said, 'Well, Mr. Meacham, where is your tent?'" When Meacham replied that his tent had not yet come down the bluff, Canby ordered his own tent prepared for the commissioners. The civilians finally talked him out of it. [5]

Meacham was also struck by the relative freedom given to such Modoc emissaries as Bogus Charley when they visited the camp during negotiations. They were shown the mortars; they watched the signal men communicate with the forces to the east. All these would, hopefully, impress the Modocs and perhaps frighten them. That they did not was confirmed by Captain Perry, "It was no unusual thing . . . to see an Indian appear on the top of Jack's Stronghold and mimic with an old shirt or petticoat the motion of our flags. [6]

Signal Rock was a simple outcropping of broken rock about 50 feet above the camp, on the side of the bluff. A photograph taken at that time may easily be related to the site today. From here, an alert signal officer, Lieutenant Adams, spotted the attack on the peace commissioners. Immediately north of Signal Rock is the peculiar outcropping known as Schonchin's Rock. Although this formation is not known to have played any direct role in the story of Gillem's Camp, it apparently attracted the soldiers' attention as a curiosity just as it attracts the visitors' today. The photographer who took pictures of the camp in 1873 was careful to include a shot of Schonchin's Rock.

Another 200 yards to the north, closer to the base of the cliff, is located Toby's Cave. This is a natural cave in a large red volcanic outcropping. The cave opening faces east and in 1873 would have overlooked Tule Lake. Today it is outside the park boundary. According to contemporary sources, it was here that Toby Riddle and her husband lived when they were interpreters for the peace commission. And it was here that the hostile Modocs would sometimes stay overnight when visiting the camp to arrange for future meetings.

As far as it is known, prostitutes did not make the journey to Gillem's Camp. But the persistent sutler did. Whether or not he sold liquor or beer to the troops is not clear; he did, however, a good business in tobacco (at one time, $1.50 per pound), soap, clothing, and other necessities. Edward Fox, correspondent for the New York Herald gave a glimpse of the merchandizing, "The squaws also brought in several bags of feathers the other day, which they traded to the sutler for provisions and clothing." Meacham records that the sutler's name was Pat McManus. [7]

Although morale was never very high for much of the time Gillem operated this camp, the troops did receive their mail. On February 26, the Yreka Journal announced "that a semi-weekly mail will be carried between Yreka and Gen. Gillem's Headquarters, leaving Yreka every Wed. and Sun. mornings." [8]

During the time Gillem's Camp was in existence, a photographer named Eadweard Muybridge came up from San Francisco to catch the scene for all posterity. As far as it is known, Muybridge was the only photographer present during the war. From his camera came the pictures that in a glance tell more about Gillem's camp than all the written records together.

Besides the officers and enlisted men, there was another army, a civilian one, at Gillem's Camp. Packers, teamsters, expressmen, guides, interpreters, boat builders, representatives of the press, even women and children milled about. When Maj . James Biddle led his troop to the Lava Beds he also brought his 6-year-old son, Dave. At Gillem's Camp, young Dave became the good friend of General Canby. He spent some time each day visiting the hospital and also "went to the funeral of every soldier who succumbed." According to his mother he and an Indian boy of the same age went fishing in the lake one day at the edge of the camp. Some Indians fired at the boys, but young Dave "coolly strung his fish before leaving." [9]

When she learned that her husband was wounded, Mrs. Alfred Meacham came down from Umatilla, Oregon, by rail, stage, and army ambulance to be with her husband. She arrived in the vicinity just as the second battle of the Stronghold was in progress. When the Army refused to let her come to Gillem's Camp itself, she waited at the mouth of Lost River. As soon as the doctors thought it advisable, Meacham was taken by boat across Tule Lake to join his wife. [10]

Another woman, equally determined, did arrive at Gillem's Camp. When Mrs. Harris of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, learned that her son, Lt. George M. Harris, had been seriously wounded in the disastrous Thomas patrol, she boarded a train for San Francisco, then traveled north toward the Lava Beds. An officer at Gillem's Camp wrote, "my attention was called to a strange object traveling down the trail, and which could not be made out properly until a gray lace streamer floating behind established . . . that it was a lady's veil." Mrs. Harris reached the Camp only one day before her son died. Sadly, she accompanied the remains back on the long journey home. [11]

It is somewhat surprising that none of Muybridge's photographs show the boats that were put on Tule Lake. The Yreka newspaper reported their presence as early as April 12, 1873, but it did not know if there were two or three. These small boats served a very useful function in providing communication between Gillem's Camp and Mason's Camp on the east side of the Stronghold. They were, too, a source of danger for on the "evening of May 12 Generals Gillem and Davis, and several others, crossed the lake from Colonel Mason's camp during a heavy gale and came near losing their lives, the boat becoming almost unmanageable." The boats also carried the wounded from the Stronghold after the April battle to the hospital at Gillem's Camp. This means of transportation was infinitely less painful than being bounced over the lava. [12]

The "general field hospital" was established under the direction of Asst. Surg. Calvin DeWitt. When he transferred to Mason's Camp on April 8, Actg. Asst. B. Semig replaced him. The chief medical officer for the whole expedition, Asst. Surg. Henry McElderry, was also at Gillem's Camp and took an active part in the hospital's activities. McElderry described the hospital:

The only two hospital tents at hand were put up for a ward; another ward was constructed of framing timbers, cut from the neighboring bluff: this frame being covered with paulins and having a door cut in front and rear. Five wall tents were put up and served as another ward. Bed sacks were filled with hay. A common tent, raised about three feet from the ground and stockaded, served for a kitchen. A hospital fly tent stretched from rear of one of the wards to the front of the kitchen tent, served for a convalescent mess tent. The dispensary and office were located in two wall tents joined together and opening into each other. The hospital steward on duty with the command also had his bed in the rear tent. [13]

As the casualties poured in, first from the attack on the peace commissioners, then the second battle of the Stronghold, and finally from the Thomas patrol, the doctors and the hospital steward found themselves busy indeed. McElderry was quite proud of his staff, especially of Cabaniss whom he considered to be a brave man when under fire. The infantry and cavalry officers of the command raised money among themselves to buy milk, eggs, and chicken to supplement the patients' diet.

Following the disastrous attempt to remove the wounded from the lava beds after the attack on Thomas, some unnamed person devised "a form of mule litter, something like a reclining chair, to be strapped on a packsaddle on a mule's back." McElderry reported that 12 of these mule litters were built and were quite satisfactory. However, there is no specific mention of their actually being used in a combat situation. [14]

Very little evidence of Gillem's Camp remains to be seen today. Among the few rock ruins is a large circular structure sitting on the higher ground about the middle of the camp sight. Its rock wall is three or four feet high today and it is 50 feet in diameter. Muybridge's photographs show that the structure had roughly the same dimensions in 1873.

This enclosure is today often called the "howitzer pit." However, as was discussed above, the howitzers were not at Gillem's Camp but at Mason's across the lava beds. The only evidence uncovered that might have a bearing on the purpose of this structure is found in Meacham. While he lay wounded in the hospital tent, his brother-in-law visited him and told him that a Modoc, Long Jim, was being held prisoner "in the stone corral." The guards had dreamed up a plan whereby they would pretend to fall asleep, Long Jim would try to escape, then the soldiers could justifiably kill him. The plan was put into effect with one guard sitting in the gateway, the others, outside. Long Jim played their game, leaped over the wall, and got safely away despite the guards efforts to shoot him. [15]

It is from Meacham's not-always-accurate pen that we get some information concerning the distribution of the companies. Although not present, Meacham believed that the various companies lined up in front of their own tents when the attack on the peace commissioners occurred. According to his description, the 4th Artillery batteries were in the tents at the northeast corner of the camp, while the cavalry troops occupied the southern part of the camp, in the depression. He did not make clear where the two infantry companies were situated. [16]

On the outskirts of the camp, the troops erected a series of small rock outposts. These were one or two-man shelters, undoubtedly thrown up by the regularly posted guards. A 1951 report said that as of that time there were 15 of these fortifications still [17]

One other stone structure remains at the camp today. Toward the south, close to the base of the bluff, stands the rock wall that enclosed the temporary cemetery established in April 1873. Two soldiers had already been buried there, on January 17, during the first battle of the Stronghold: an unknown soldier of the 1st Cavalry, and one Brown of the Oregon Volunteers. Probably their graves caused the command to use this same site.

No good report on the cemetery has survived from the time Gillem's Camp was actually occupied. Meacham, however, came forth with one small bit of macabre humor. When he looked out the tent flap from his hospital bed, he saw two soldiers heading toward the cemetery, "one carries a spade, the other a small, plain, straight box, in which is the leg of a soldier going to a waiting-place for him." Meacham was correct; Sergeant Gode, Company G, 12th Infantry, had his leg amputated, buried, and entered on the army records, April 19.[18]

In August 1873, after the war was over, Lt. George Kingsbury took a detail of six men and a guide from Fort Klamath to the lava beds to transfer bodies from different battle sites throughout the area to the cemetery at former Gillem's Camp. At the scene of the attack on the Thomas patrol, Kingsbury recovered thirteen bodies. From there he marched to the Stronghold where he located two more. These remains were taken to the cemetery, all but one were buried, and the graves carefully marked with headboards. The unburied body was Lt. Arthur Cranston's. Kingsbury sent it back to Fort Klamath and from there it was shipped to the Presidio, San Francisco, for final burial. In his report, Kingsbury did not say whether he carried out that part of his orders which directed him to enlarge the stone pile that marked the spot where General Canby had fallen. [19]

A report dated the next year, July 2, 1874, apparently prepared by someone who had recently inspected the cemetery at the lava beds, gives the only detailed record of the number of burials. Including seven unknowns and the leg of Sergeant Gode, the total number was 30. This figure agrees with the count made by John Muir the same year. The report also noted that the cemetery wall had broken down in four places. [20]

In 1875, the department commander ordered that the remains at Gillem's Camp cemetery be disinterred and reburied at Fort Klamath. He also directed "a crude monument of rocks and stones" erected at the cemetery and at the site of the Thomas patrol's fight and, finally, that the existing monument to General Canby be enlarged by the addition of rocks. [21]

In November, Lt. F. E. Ebstein reported on his efforts to accomplish the tasks. At the scene of the Thomas affair he found a few bones which he collected and buried in the cemetery. He also erected "a crude monument" at the site. From there he marched to the site of Canby's death. He erected a "monument of stones, four feet high, placing in the top of the same a wooden tablet inscribed as follows: 'Major General E. R. S. Canby U.S.A. was killed here by Modoc Indians April 11, 1873.'" The next day Ebstein sent a detachment to the camp sites at Land's ranch and the Peninsula. This detachment disinterred two remains at Land's but "found the bodies of the three men buried on the Peninsula in such state of decomposition that they could not be moved at present."

The lieutenant ran into the same problem at the cemetery. His men opened all the graves but was forced to leave 14 there. "The coffins, originally roughly constructed," he wrote, "had in all cases separated and the smell arising . . . was so offensive that the men turned sick." Ebstein recommended that the remainder not be removed for another year. Two wagons carried the fifteen coffins back to Fort Klamath. No mention was made of Sergeant Gode's leg. [22] One year was not enough. In the fall of 1876, a Fort Klamath corporal rode down to Gillem's camp, examined one grave, and grew ill. He also found the stone fence in very bad condition and repaired it. [23] The records of Fort Klamath do not disclose when the rest of the bodies were moved from Gillem's Camp. Only the cemetery wall, rebuilt many times, still stands.

On May 19, 1873, Capt. E. V. Summer, aide-de-camp to Colonel Davis, issued the order, "The enemy having left the lava bed it becomes necessary to break up the present encampment and put the troops more actively in pursuit." The pack mules made their way back up the bluff, carrying the tents and supplies. Soon there was only the wind, the call of birds, "the lake . . . fairly blooming in purple light," and the lava.

|

| Signal Rock on the bluff immediately above Gillem's Camp. The lower end of the trail down Gillem Bluff may be seen toward the left. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

thompson/chap12.htm

Last Updated: 11-Nov-2002