|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 1:

When Rivers Ran Free

|

This was our country. God created this Indian

Country, and it was like he spread out a big blanket, and he put the

Indians on it. The Indians were created here in this country, truly and

honestly, and that was the time our rivers started to run. Then God put

fish in the rivers, and he put deer and elk in the mountains and buffalo

upon the plains, and roots and berries in the field, and God made laws

through which there came the increase of fish and game. When the

Creator gave us Indians life, we awakened and as soon as we saw the fish

and the game we knew that they were made for us. For the men God gave

the deer, the elk and the buffalo to hunt for food and hides; for the

women God made the roots and the berries for them to gather, and the

Indians grew and multiplied as a people, and gave their thanks to the

Creator. When we were created we were given our ground to live on, and

from that time these were our rights.

--Statement of Colville and Okanogan Chiefs, 1925 [1] |

Native or aboriginal people have lived in the Upper Columbia region for over 9,000 years. Extensive archaeological excavations of several sites at Kettle Falls suggest seven distinct periods that show times of relative abundance alternating with periods of scarcity. The salmon fishery at Kettle Falls, so significant in historical times, varied in importance for these early people; during one prolonged period, heavy flooding interrupted the salmon runs, forcing people to depend on other available food sources. Approximately 3,400 years ago, however, after salmon reestablished their runs as far as Arrow Lakes and eventually to Columbia Lake in British Columbia, people once again exploited this resource at Kettle Falls. The activity increased dramatically about 2,600 years ago, and the fishery became a prominent gathering place where people from a wide region came to fish, trade, and socialize. By the time of contact (when Indians first encountered non-Indians), Salish speakers at the falls included the Shwayip (Colville), whose territory encompassed the Columbia River from the fishery at Kettle Falls upriver to the Little Dalles (south of Northport) and downriver to the Inchelium area; the Sinaikst (Lakes) people, with lands to the north; the Sanpoil, with lands to the southwest; and the Okanogan even farther west. Those speaking Flathead dialects of the Salish language included Spokane, Kalispel, Flathead, and Chewelah, while the Kutenai spoke a language unrelated to others in the region. [2]

Indians of the Upper Columbia region felt the impact of Euroamericans long before contact. Horses, first brought to the American Southwest by Spaniards, gradually moved north through inter-tribal trading and arrived in the Columbia Plateau region ca.1730-1750. These animals dramatically increased the mobility of many tribes and enabled some to travel east to the Plains region to hunt buffalo. A more insidious harbinger of Euroamericans arrived in the form of epidemics that decimated large numbers of native people. The first outbreak of smallpox in the Colville region hit in 1782-1783, prior to any direct contact with non-Indians. In the mid-nineteenth century, a rapid succession of both smallpox and measles epidemics between 1846 and 1853 killed many Indians and further weakened the tribes. [3]

Following early Spanish and Russian claims along the Pacific coast, American and British interests spent several decades vying for control of valuable lands and resources of the Pacific Northwest. The initial attraction was furs, especially for the lucrative sea otter trade with China. Farther inland, beavers were prized for their pelts; the soft underfur was felted and turned into top hats, a popular fashion accessory of the day.

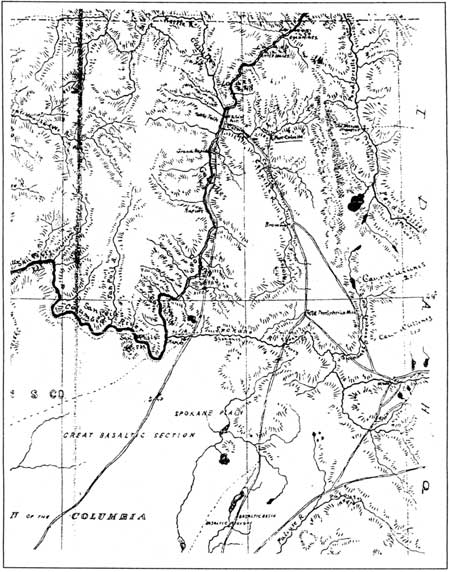

Fur traders approached the Inland Northwest from both east and west. The first to document his travels through the region was David Thompson, an experienced explorer, map maker, and trader with the Canadian-based North West Company. He had two primary objectives as he moved into the region: establishing a chain of trading posts and exploring the Columbia River to its mouth. Thompson and his small group of men built Kullyspell House on Lake Pend Oreille and Saleesh House farther up the Clark Fork River in the fall of 1809. Spokane House, near the junction of the Little Spokane and Spokane rivers, followed the next year. [4]

Thompson spent his limited time in the region exploring and mapping trails and river courses. His arrival at the Columbia River in June 1811 added Euroamericans to the diverse mix of cultures already found at Kettle Falls. The salmon season was about to begin, and Thompson was impressed with the village he found at Ilthkoyape (his transcription of the native name for Kettle Falls). He described sheds about twenty feet wide and from thirty to sixty feet long, made from boards hand-split from large cedar logs. These structures had a covering of boards and mats to protect the salmon being smoke-dried on poles inside. [5]

|

| Indians fishing from platform and rocks at Kettle Falls, no date. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3245). |

Later observers described the activities at the fishery. Artist Paul Kane visited in August 1847 at the height of the salmon run when the fish moved in "one continuous body . . . more resembling a flock of birds than anything else in their extraordinary leap up the falls, beginning at sunrise and ceasing at the approach of night." Father Pierre Jean DeSmet watched men catching up to three thousand salmon each day, using spears and J-shaped baskets placed in the falls. After cleaning and filleting the catch, the women hung the fish to dry in the sheds. Excess fish were used later for trading. [6]

Thompson built a canoe while visiting the busy fishery and then launched his voyage down the Columbia, reaching the Pacific Ocean in July 1811. To his great disappointment, he found that upstart Americans from the Pacific Fur Company already had established Fort Astoria. Two Astorians who accompanied him on his return trip up the Columbia built three posts, two of which competed directly with ones previously established by Thompson. These included Fort Okanogan (1811) at the mouth of the Okanogan River; Fort Spokane (1812), just a stone's throw away from Spokane House; and another post (1812) near Saleesh House. The rivalry was short-lived, however. The outbreak of the War of 1812 helped convince the Astorians to sell their assets to the North West Company, which in turn merged with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in 1821. [7]

Within a short time, HBC officials decided to cut expenses by moving the district headquarters from Spokane House to Kettle Falls. Sir George Simpson, HBC Governor in North America, preferred the new location for its easy access to the Columbia River as well as its agricultural potential. He negotiated with an Indian leader who gave a tract of land for a trading post but refused to share the Kettle Falls fishery. The Spokane Indians were unhappy with the loss of a post in their territory. "The Spokans [sic] will not be pleased at the removal of the fort," Simpson wrote to HBC employee John Work in April 1825. "You must secure the Chiefs with a few presents besides fair words." [8]

Construction of Fort Colvile began in August 1825 but proceeded slowly, due in part to the apparent ineptitude of some of the crew. The new quarters were ready by the following spring and provided a log stockade surrounding a number of log buildings, constructed in the post-and-sill style common to HBC posts. Simpson described Fort Colvile in the early 1840s as "cleaner and more comfortable" than any other fort between there and the Red River. [9]

Simpson's belief in the agricultural potential of the Colville Valley proved accurate. By 1841 the HBC farm spread over two hundred acres, two-thirds of which grew crops of wheat, potatoes, barley, oats, corn, peas, and garden produce. The company's cattle herd had increased from the initial bull and two heifers in 1825 to nearly two hundred by 1841. Farm facilities expanded in 1830 with the construction of a water-powered grist mill on the Colville River. In addition to supplying its own needs, Fort Colvile sold cheese, butter, and pork to the Russians at Sitka, Alaska, and sent flour, cornmeal, pork, and other products to HBC operations throughout the Pacific Northwest. [10]

|

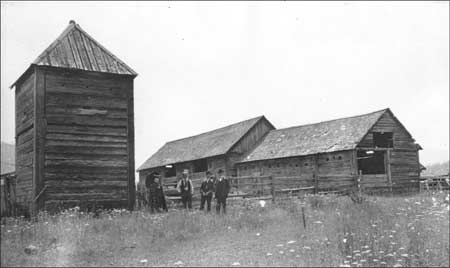

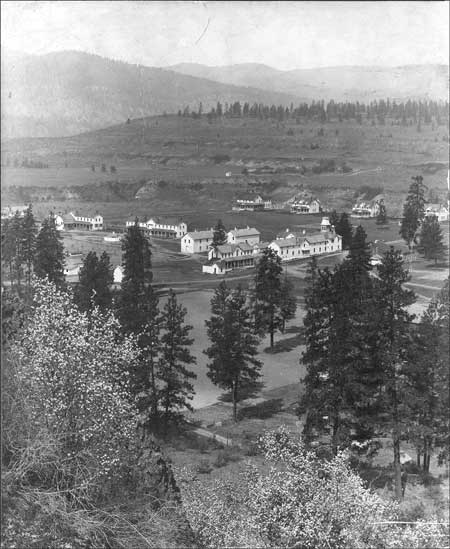

| Fort Colvile buildings, no date. Note the post-and-sill construction of the log structures. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2443). |

HBC's principal business was not farming, of course, but furs, and it enlisted the local Indian population in this endeavor. Indians did most of the trapping in the Colvile District, trading pelts from beaver, otter, muskrat, bear, marten, and other animals for weapons (knives, guns, and ammunition), tools (traps, axes, and firesteels), domestic items (wool blankets, cotton cloth, mirrors, and beads), and tobacco. HBC generated considerable money from this trade. "We made an enormous profit on the Indian trade," wrote HBC employee Ross Cox in 1832. Traders would exchange a gun, worth approximately $6, for twenty beaver pelts, worth $40 to $50 each. Similarly, a couple of yards of cloth, worth less than $1, traded for eight skins. [11]

The trade relationship altered many aspects of traditional native life. Indians quickly became dependent on traders for material goods, particularly ammunition and tobacco. Although Fort Colvile was not a traditional winter camp, it attracted Indians who began to winter nearby, taking food from the traders during hard winters such as 1830-1831. Gifts of food and tobacco to chiefs and other Indian leaders gradually eroded the power of traditional leaders until the HBC traders became authority figures in the region. HBC employees encouraged the men to trap during the usually sedentary winter months, with varying success. Prostitution, drinking, and gambling-induced poverty all had negative impacts on traditional culture. On a more positive side, intergroup warfare appears to have decreased after traders arrived. Paradoxically, the acquisition of guns and ammunition put the Interior Salish on a more even footing with the Plains tribes. [12]

When missionaries came to the Upper Columbia region, determined to change Indian lives, native people were somewhat prepared for their arrival. Many tribes had contact with French Canadian and Iroquois trappers whose Roman Catholic practices exposed Indians to a new set of beliefs. HBC Governor Simpson sent the sons of two influential chiefs to the Anglican missionary school on the Red River (now Winnipeg) in 1825; they returned four years later and began to teach about Christianity. One of these young men, Spokan Garry, taught hymns, prayers, and the practice of saying grace before meals, all of which appealed to Indians who had traditionally practiced a variety of rituals. [13]

The first missionaries came in direct response to a delegation of Flathead and Nez Perce Indians who traveled to St. Louis in 1831. Their request for religious instruction for their people resonated with Americans, fueled by a religious revival and interest in proselytizing. The first missionaries went to the Willamette Valley in Oregon Territory in 1834, and two years later others settled among the Cayuse near Walla Walla and the Nez Perce at Lapwai. Samuel Parker, an itinerant Protestant missionary, came to Fort Colvile in 1836 and is credited with giving the first church service there. When Elkanah Walker and Cushing Eells and their wives arrived at the fort in 1838, HBC trader Archibald McDonald suggested the site of Tshimakain (Chamokane), now Walker's Prairie, for their church. These missionaries soon had a congregation of two hundred Spokane Indians, but the numbers did not hold up. During their ten years there, Walker and Eells had little success in changing the nomadic lifestyle of the Spokane people or in converting many to Christianity. They closed the mission in June 1848, a few months after disillusioned Cayuse Indians had turned against their missionaries and murdered them at Waiilatpu. [14]

Catholics joined Protestant missionaries within a short time. Two Jesuit priests stopped briefly at Fort Colvile during the winter of 1838-1839 to minister to HBC employees and their families. One of them returned the following summer for a longer stay, resulting in many Indian baptisms and confessions. More importantly, the goodwill he generated laid the groundwork for a Catholic mission there. The indefatigable Father Pierre Jean DeSmet spent ten days at Fort Colvile in May 1841, continuing the pattern of short visits to baptize and preach. Father Anthony Ravalli built the first chapel for the Indians at Kettle Falls in 1845. This was followed two years later with the construction of the more permanent St. Paul's Mission on the hill above the falls. Catholic missionaries visited the Spokane people during this same period, coming from a mission among the Coeur d'Alenes. After Chief Baptiste Peone requested a permanent missionary for the Upper Spokane, Father Joseph Cataldo took up residence there in December 1866 and built St. Michael's Mission. Other Catholic churches in the region included the Church of the Immaculate Conception, near the U.S. Army post, and St. Francis Regis. [15]

Like the fur traders, missionaries had considerable impact on the culture of native peoples since they worked to totally change the traditional religious and social systems. They preached against the practice of polygamy, despite its important place in the native cultural, political, and economic systems. They urged men to take up farming and failed to understand their reluctance to assume what was considered women's work. They hoped to end the nomadic lifestyle of Indians and to have them settle in small cabins; such dwellings, however, were not suitable for the traditional extended family. Those Indians who did become Christians faced many problems: non-Indians still saw them as inferior while Indians often despised them for giving up the ways of their forefathers. [16]

|

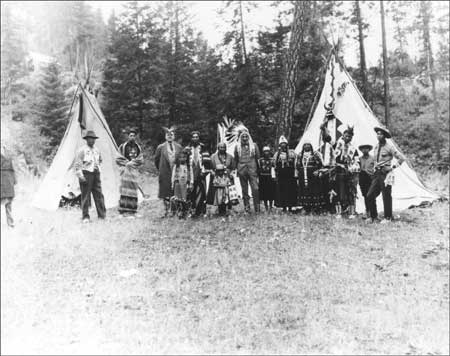

| Interior Salish Indians in camp, ca. 1935. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2506). |

Tensions between Indians and non-Indians increased dramatically during the 1850s. Following the creation of Washington Territory in 1853, Isaac Stevens was appointed both governor and ex officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs; it was in the latter position that he was mandated to take a census of the tribes and negotiate treaties for the United States. These treaties were key to the eventual construction of the transcontinental railroad since all Indian claims to land along the route had to be extinguished. Stevens called for a council in Walla Walla in 1855. Prior to meeting with the governor, leaders of several tribes, including Yakama, Walla Walla, and Nez Perce, met in the Grand Ronde Valley in Oregon to devise a strategy for outwitting Stevens. If each chief demanded his tribe's entire territory for a reservation, they reasoned, then non-Indians would be left without any land. Stevens had a spy among the Indians, however, Hollolsotetote (Lawyer) of the Nez Perce, who revealed the plan to Stevens. Lawyer's announcement at the council that he would sign the treaty upset the other chiefs, who were further were alarmed by Indian Agent Joel Palmer's explanation that non-Indian settlement could not be stopped. By the end of the council, the tribes had ceded sixty thousand square miles and reserved substantially less acreage for three reservations, an annual payment of $500 to the chiefs, and promises of agricultural equipment and provisions worth close to $650,000. [17]

Tribal resentment exploded that summer, fueled by clashes with miners trespassing on land reserved for Indians. In the fall of 1854, an HBC employee discovered gold on the sandbars of the upper Columbia River, in the vicinity of Fort Colvile. When the news leaked out a few months later, a predictable rush of miners flooded the region just as Stevens was concluding the treaty process. Colville chief Peter John closed his lands to non-Indians in August 1855, and the following month a number of miners and an Indian agent were killed by Yakamas. A state of war erupted, and both sides remained on high alert during the next three years. Stevens met with leaders of the Spokane, Coeur d'Alene, and Colville tribes late in 1855 in an effort to contain the war. They reached no agreements at that time, however, and a meeting planned for the following spring never occurred. [18]

While the Colvilles and their neighbors remained relatively aloof from the fray, the Spokanes allied themselves with the Coeur d'Alenes, Yakamas, Kalispels, and Palouse to protect their lands from further encroachment from non-Indians. A frightened group of settlers met at Fort Colvile in November 1857 and petitioned the government for a company of soldiers to protect them. Discovery of gold on the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1858 intensified the problem. Col. Edward J. Steptoe and his two hundred troops felt the full force of Indian wrath when they ventured out from Fort Walla Walla in May, only to be soundly defeated by a coalition force of between six hundred and sixteen hundred Indians. The victory, while sweet, was short-lived. Col. George Wright and his Army troops won two decisive battles later that summer and ended the war. In an effort to permanently cripple the Indians and ensure that they could never fight again, Wright ordered the killing of eight hundred horses, a devastating blow to a people whose welfare and wealth depended upon these herds. Troops also destroyed grain crops and stores of food in Spokane territory and then hung fifteen Indians for alleged murders. The war was over, but the memory lived on. [19]

Following the defeat of the interior tribes, the U.S. Army responded to the request for a post in the vicinity of HBC's Fort Colvile to monitor the border and help prevent future trouble between settlers and Indians. Two companies of the 9th U.S. Infantry, under the command of Pinkney Lugenbeel, arrived in the spring of 1859 to begin construction of Fort Colville, located about three miles east of the present town of Colville. Within four years, it encompassed forty-five buildings. Pinkney City, an occasionally wild settlement, grew up near the army post and came into prominence during the 1860s as a supply point for mines in the region. Supplies arrived from Walla Walla via pack trains, and later freight wagons, on a major trail through the Colville Valley. [20]

Miners initially concentrated on placer gold, found most readily in sand and gravel deposits in rivers and streams. The prospectors included many Chinese, who frequently worked claims abandoned by their Euroamerican counterparts. A store at Hawk Creek served nearly three hundred Chinese miners working along the river in the late 1870s. Within a few years, the region's Chinese population had grown to approximately one thousand, making more Chinese than white miners along the Upper Columbia. Their numbers dropped, however, as ore deposits decreased and restrictive laws increased. Some returned to China, while others moved to cities for more lucrative work. [21]

|

| Mining with a sluice box on the Columbia River, 1890s. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives 908). |

The mining boom stimulated the growth of agriculture in the region, particularly in the relatively temperate Colville Valley and in the Columbia Valley south of Fort Colvile. Some former HBC employees had taken up farms in this area, starting as early as the 1830s. They supplied food to the fur trade post and later sold agricultural products to the Army and the burgeoning mining population. In addition to the non-Indian farmers, many Colville and some Lakes Indians farmed their traditional lands in the same area. Some continued their semi-nomadic lifestyle at least part of the year. After planting their crops in the spring, they left for their annual cycle of root gathering and fishing. They then returned to their farms in the fall to harvest crops from their untended fields. Indian agent William P. Winans reported that Indians apparently had more success with garden produce than their non-Indian neighbors due to their warmer growing season at the mouth of the Colville River. "I purchased early in July peas, carrots, beets, onions, cabbages, etc.," he wrote, noting that the Indians "are the only ones that have so far successfully cultivated the tomato, the frosts not troubling them as early as those living further up the valley." [22]

Winans was one of a series of Indian agents who dealt with tribes on behalf of the government during this period. Pinkney Lugenbeel had taken on these duties as early as 1861 in connection with his role at Fort Colville. From 1868-1872, the agent was known as the "farmer-in-charge." His duties included encouraging agriculture in the belief that this would help Indians adapt to white culture. Once native people had settled on individual farms, the government planned to open "excess" lands for non-Indian settlement. [23]

By the early 1870s, Indians realized that it was in their interests to secure a reservation since settlers were taking over much of their traditional lands. The government also believed that it was important to move non-treaty Indians to reservations to finally establish which lands were available for white settlement. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Washington Territory, T. J. McKenny, recommended that the Colville reservation be an area at least forty miles square that included "the old fisheries south and west of the Hudson's Bay trading post." An Executive Order of April 9, 1872, set aside a reservation that included roughly all of northeastern Washington east of the Columbia River and north of the Spokane River, to accommodate Colville and neighboring tribes. [24]

Agent Winans had a different view, however. As a merchant, he perceived development of the Colville area proceeding more smoothly without Indians; this was a view probably shared by many settlers. Winans wrote to his Congressional delegate and recommended that the reservation be moved to the other side of the Columbia River. The Executive Order of July 2, 1872, accomplished his goal with a 2.8 million-acre reservation bounded on the north by Canada, on the west by the Okanogan River, and on the south and east by the Columbia River. Winans saw the proposition as a win-win situation. The earlier reservation was too small for the large Indian population, he claimed, and did not have enough grazing land for their herds. Further, since most of the good agricultural land was already taken by non-Indians, they would have to move before Indians could have the land. [25]

Colville leaders appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant in the strongest terms, saying that this move would deprive them not only of their farms and hay lands, but also their homes, villages, and mission that were all east of the Columbia. They feared being unable to rebuild if forced to move and worried that "the little progress in civilization we made already will be lost." [26] Special Commissioner John P. C. Shanks, assigned to investigate Indian affairs, reported on conditions in the Colville area in 1873. He noted the duplicity of Agent Winans and called the forced move to the new reservation "expensive, troublesome, dishonorable, and wicked." [27] Ultimately, the effort was futile and most Indians had moved to the reservation by the 1880s. The government reached agreement to move the Moses band of Columbia Indians to the reservation in 1883, followed by Joseph's band of Nez Perce two years later. [28]

The Spokane Indians were not happy with this new reservation, however, since the area north of the Columbia was outside their traditional territory. In addition, most Spokane tribal members considered themselves Protestants, but most Indians on the newly formed Colville Reservation were Catholics. They refused to move, claiming that they would starve in the barren land north of the river. Agent John Simms advised the government that these people would not move voluntarily and warned of potential war if they were forced off their lands. Members of the Lower Spokanes negotiated with Col. E. C. Watkins, an Indian Inspector, in August 1877, with the result that land known as "Lot's Reservation" was set aside for their use. They pushed for additional land to accommodate the whole tribe and achieved some boundary adjustments reflected in the Executive Order of January 18, 1881. This officially established the Spokane Reservation with 154,898 acres. The Middle and Upper Spokanes did not want to move to the new lands until they had been compensated for the loss of their traditional lands, by then occupied by the rapidly growing city of Spokane Falls. In an agreement signed in March 1887, tribal members ceded their lands and agreed to move in return for approximately $127,000 for building materials, cattle, seeds, and farm equipment. Most of the Upper Spokanes moved to the Coeur d'Alene Reservation in Idaho while the Middle Spokanes moved to the Spokane Reservation. [29]

|

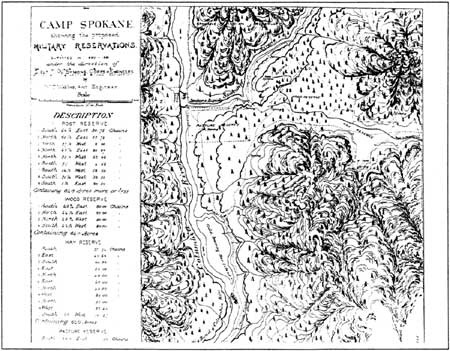

| Map of Camp Spokane and vicinity, 1880-1881. (Frame 774, RG 049, WSA-ERB, Cheney.) |

General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the Department of the Columbia, approved the site for a new military post, at the confluence of the Columbia and Spokane rivers, in 1880. The advantages of the new location included proximity to the new Northern Pacific Railroad line at Spokane Falls to facilitate rapid movement of troops if needed. Howard relocated a garrison of the 2nd Infantry from Camp Chelan to Camp Spokane in October 1880, and they were joined over the next five years by troops from Fort Colville. An Executive Order in January 1882 made the camp a military reservation, and the name changed to Fort Spokane a month later. The original tents and log cabins were replaced eventually with forty-five buildings suitable for a permanent six-company post. The fort's layout featured a large parade ground surrounded by frame and brick buildings. This was a time of relative peace in the Inland Northwest, however, and the troops at Fort Spokane saw little action aside from routine drills, parades, and patrol duty. In an effort at efficiency and economy, the Army decided to consolidate Fort Spokane with two other regional posts, with the new post to be built near the city of Spokane. Before this change was completed, troops left Fort Spokane for the last time in April 1898, heading to the Spanish American War. The Army did not reoccupy the post after this date. [30]

|

| View of Fort Spokane from the south, ca. 1903. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3014). |

The Secretary of War turned the abandoned post over to the Secretary of the Interior for an Indian School on August 28, 1899. At that time, the federal government had been funding Indian schools for nearly eighty years. A new off-reservation industrial school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, opened in 1879 and soon became the model for Indian boarding schools. The philosophy moderated ten years later, with increased emphasis on day schools for younger children, boarding schools for intermediate students, and off-reservation industrial schools to carry students through the eighth grade. [31]

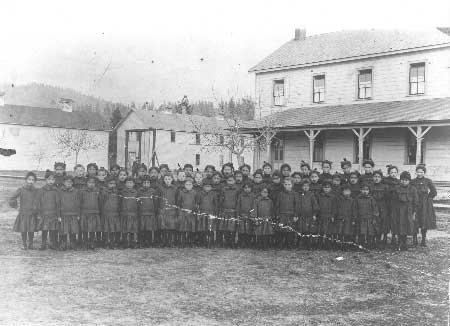

The Indian Service saw the abandoned buildings at Fort Spokane as a good site for a boarding school to supplement the day school at Nespelem. The school opened on April 2, 1900, serving up to two hundred Indian children. The underlying philosophy of all Indian schools was the destruction of Indian culture, which, it was believed, would lead to assimilation into American culture. The children at the Fort Spokane school attended classes only half a day, with the remainder of each day devoted to vocational training. The boys practiced farm skills, such as feeding chickens, milking cows, or working in the garden. The girls, on the other hand, learned domestic work such as cooking, laundry, ironing, and making beds in the dormitory. Children who ran away were returned to the school where they spent time in the former military guardhouse as punishment. Enrollment dropped and expenses increased, causing the school to close in 1908. A hospital that followed the school specialized in treating respiratory diseases in children from reservations throughout the West. Again, rising costs forced its closure after just two years. Another hospital operated there from 1918 until 1929, when the facilities were closed permanently. [32]

|

| Group of girls who were students at the Indian School at Fort Spokane, ca. 1903. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3016). |

The displacement of Indians continued as more non-native people settled permanently in northeastern Washington. Interest in the mining and agricultural potential of the Colville Reservation led to the cession of the north half in 1891, a move bitterly opposed by Sanpoil and Nespelem tribal members. This agreement allowed 1.5 million acres to return to the public domain for eventual settlement by non-Indians. The north half of the Colville Reservation was opened to mineral entry in 1896, followed two years later by the opening of the south half. This gave non-natives claims on even more Indian land. The final blow came with the allotment of both the Colville and Spokane reservations in the early 1900s. Such division of reservation lands was guided by the General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887, under the premise that encouraging farming on individual allotment parcels within the reservations would help break the traditional social order and hasten assimilation. After each family head was given 160 acres and other individuals lesser amounts, the remainder of the reservation was thrown open to settlement by non-Indians. Indians on both reservations took allotments along the rivers wherever there was flat land. This caused a local newspaper to complain in 1914, "The Indians have taken the cream of the reservation. Their allotments cover practically all of the valleys along the streams, including the rich irrigable lands along the west bank of the Columbia." The Spokane Reservation was opened for homesteaders in 1909 and the following year for mineral entry. Settlers began claiming Colville Reservation lands in 1916. [33]

|

| Indian hospital in former bachelor officers' quarters, Fort Spokane, 1920s. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2217). |

Railroads stimulated settlement along their routes in northeastern Washington. The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad through Spokane and Lincoln counties in the early 1880s brought an influx of new settlers. Later that decade, the Spokane Falls & Northern line initiated service from Spokane Falls to Colville and brought both residents and industries to this region; this line extended to Northport in 1892 and to the border a year later. The railroads not only brought new people but also provided a way for farmers and industries to get their products to market. By 1900, farming was the dominant land use in the Columbia valley, with particular emphasis on orchard crops. While many farmers pumped irrigation water from the Columbia, those associated with the Fruitland Irrigation District used water from the Colville River, which reached their farmlands with an extensive ditch and flume. Grain and livestock came to dominate the more arid lands of Lincoln County. [34]

The perceived potential for these arid lands stimulated investigations into ways to bring water to the Columbia Basin. Two plans were extensively examined, one to develop a gravity plan to bring water from the Pend Oreille River with a dam at Albeni Falls and one to pump water from the Columbia River. The pumping plan prevailed and called for construction of a dam at Grand Coulee and an equalizing reservoir to provide enough water to irrigate 1.2 million acres. This set the stage for a project that changed the face of northeastern Washington and generated ripple effects that reverberate today. [35]

|

| Town of Peach and some of the orchards that gave the town its name, ca. 1920. Both the town and the trees were flooded by Lake Roosevelt. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2930). |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003