|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 3:

A Long Road Lies Ahead: Establishing Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area

The gates on Grand Coulee Dam had closed by 1939, starting the impoundment of the Columbia River that became Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake. Although federal and state planners envisioned recreational development for the reservoir from the beginning, they faced many other pressing issues with the massive Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, a major development designed to benefit from the dam and reservoir. Recreation planning was hindered initially by indecision over which agency should guide and manage recreation for the area. Later planning and development efforts were retarded by a chronic lack of funding and marred by interagency disputes. This made the early years of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO), from the 1940s through the early 1950s, a constant struggle for basic existence.

| The issues studied by the Joint Investigations included types of farm economy (Problems 1-3); water requirements (Problems 4-5); size of farm units (Problems 6-7); farm layout and equipment (Problems 8-10); allocation of costs and repayments (Problems 11-14); control of project lands (Problems 15-16); rate of development (Problem 17); villages (Problem 18); roads and other transportation facilities (Problems 19-21); underground waters (Problem 22); rural and village electrification (Problem 23); manufactures (Problem 24); recreational resources and needs (Problems 25-26); rural community centers (Problem 27); and governmental organization: public works programming and financing (Problem 28). [1] |

As the waters rose in the new lake, government officials began comprehensive planning for the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) hired Dr. Harlan H. Barrows, head of the University of Chicago Geography Department, as a planning consultant to work with William E. Warne, Reclamation Director of Information, and Dr. Edward N. Torbert, an economic geographer with Reclamation. The outcome was the Columbia Basin Joint Investigations that divided the planning process into twenty-eight problems to study. Over the next several years, nearly three hundred people from forty local, state, and national agencies worked on the planning. [2]

Early Planning: Committee on Problem No.

26

Two of the study problems dealt with recreation. Reclamation headed up the committee for Problem No. 25 to locate and plan rural parks and recreation areas within the boundaries of the irrigation project. Other agencies on the committee included the National Park Service (Park Service), Washington Department of Highways, and the Washington State Planning Council. The Park Service was asked to lead the much larger Problem No. 26 committee with a mission "to formulate plans to promote the recreational use of the reservoir above Grand Coulee Dam and its shorelines, not in isolation but in effective inter-relationship with the other diversified recreational assets of the Inland Empire and of contiguous areas, from all significant local, regional, and national points of view." [3] The committee grew to include nine federal agencies, nine state agencies, two outdoor organizations, and four chambers of commerce. [4]

The Park Service moved rapidly to designate the investigation leader for the Problem No. 26 committee. "We believe that the best man to handle this work . . . will be Mr. C. E. Greider," advised Conrad L. Wirth, National Park Service Assistant Director. [5] At the time of his appointment, Claude E. Greider was a State Supervisor with the agency in Portland, Oregon, and he was later promoted to Associate Recreation Planner in the San Francisco office. Greider took charge of the Problem No. 26 investigations in November 1939, beginning an association with Lake Roosevelt that lasted nearly fourteen years and encompassed the initial planning, establishment, and early development of LARO. [7]

| The Problem No. 26 Committee, headed by the National Park Service, included eight other federal agencies (Reclamation, Army Corps of Engineers, Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Indian Affairs, National Resources Planning Board, Public Roads Administration, U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, and U.S. Forest Service), nine Washington state agencies (Department of Conservation and Development, Department of Game, State Planning Council, Department of Health, Department of Highways, Department of Public Lands, State Game Commission, State Progress Commission, and State Parks Committee), two outdoor organizations (Federation of Western Outdoor Clubs and Northwest Conservation League), three chambers of commerce (Seattle, Spokane, and Ephrata), and the Associated Chambers of Commerce of Washington. [6] |

Recreation planning for federal reservoirs was a new direction for the Park Service at this time. During the 1930s, the agency administered the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) at state parks around the nation. Since most states had no comprehensive planning for their parks, the Park Service supported the Park, Parkway, and Recreation Study Act of 1936 that enabled it to work with other agencies nationwide to coordinate planning for parks at local, state, and federal levels. By 1941, thirty-four states, including Washington, had produced detailed recreation reports. That same year, the Park Service published its comprehensive report, A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States, outlining the state of parks nationwide and recommending directions for the future. [8]

As part of its expanded duties during the 1930s, the Park Service began working with Reclamation to develop recreation plans for reservoirs administered by the latter agency. Although it did not intend to remain involved in reservoirs of lesser importance, the Park Service recognized the nationally significant recreation potential of larger reservoirs behind major dams, such as Boulder Dam on the Colorado River. Nonetheless, there was considerable disagreement within the agency for many years over adding reservoir recreation sites to the National Park System. Many questioned the national significance of such areas, and some agency stalwarts believed that Lake Mead, behind Boulder Dam, was essentially a commercial playground. The National Park System had never included parklands where recreation, not preservation, was the primary focus; purists were further dismayed with the acceptance of hunting inside the boundaries of these new areas. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes shared these concerns but also saw the potential increases in appropriations if the Park Service assumed responsibility for reservoir recreation. Reclamation also saw good potential in interagency collaboration, and when it announced major investigations in 1945 to expand development of western river systems, it asked the Park Service to do a systematic survey of the recreation potential for all proposed projects. [9]

As it undertook this new role, the Park Service looked to other recreational areas for guidance. Regional Director John E. White requested enough copies of "Recreation Development of the Tennessee River System" (House of Representatives Document No. 505) for each member of the Problem No. 26 Committee. White had seen the report and told an official of the Tennessee Valley Authority that "it appears that the problems you have solved at TVA are quite identical with those facing our committee." [10] Four years earlier, R. F. Bessey, a consultant with the Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission, heard about the recreational development being done at reservoirs along the Mississippi River and noted the parallels with Bonneville Dam and its reservoir. He requested information on the planning and administration of the proposed park system. [11]

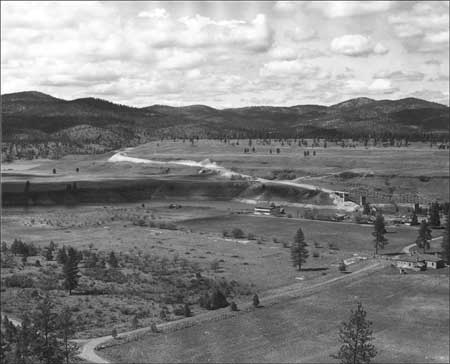

Before the committee could do much planning, its members needed to see the future reservoir area. Greider visited Grand Coulee Dam in January 1940 for a firsthand look, touring parts of the recreation area with Frank A. Banks, chief construction engineer for the dam. Later, members of the committee spent a day in mid-April traveling to several prospective recreation sites. They started up north at Kettle Falls, toured down to Hunters for lunch, and then ended with a boat trip to the dam. Despite their initial work, the committee made little progress during 1940 because the reservoir had not yet reached full pool. The terrain was rugged, and the only way to reach most of the potential recreation sites was by boat. The water was expected to reach close to maximum level early in 1941, leading to increased use of the area. Committee members recognized the need to develop policies as soon as possible to control this expected rise in visitation. Reclamation suggested using topographical maps, supplemented by a few field examinations, to develop a plan outline over the winter to coordinate both public and private developments. [12]

At this point, the committee recognized that it had gone as far as it could go by itself and could make no further progress without field investigations and plan preparations. Since neither the committee nor any of the cooperating agencies had funding for this work, all agreed to recommend that the Park Service be designated as the agency in charge of recreation planning, development, and administration of the reservoir. "They feel that the Service will undoubtedly have this responsibility eventually," wrote Greider, "so why not now at the beginning of planning and development work." [13] The suggestion was not unexpected, and the Park Service Regional Director forwarded the idea to Washington, D.C., with his full support. At its November 1940 meeting, the committee made its official recommendation that the Park Service assume responsibility for doing field studies and plans, but it held off designating any agency for future development and administrative work. The Park Service agreed to undertake field studies and Master Plans later that month. Banks immediately squelched any attempt to appoint Reclamation as the ultimate administrator for recreation at the reservoir because this was not a function of his agency and its personnel did not want the responsibility. [14]

The National Park Service Arrives at the

Columbia River Reservoir

|

Early in 1939, a Spokane newspaper was flooded

with suggestions for naming the lake that was beginning to form behind

Grand Coulee Dam. Possibilities included Lake Beautiful, Lake President

("in honor of the highest office of our nation and government"), and

Lake Reclamation ("That carries a world of possibilities"). Not all

were flattering, however. One man had a number of suggestions including

Devil's Lake or Bankruptcy Lake ("Either name would be appropriate").

For the "weak-minded idol worshipers," he proposed naming features such

as "Roosevelt bay, Ickes isle and Eleanor point . . . . Let us name the

dam [sic] lake right while we are about it."

In 1940, the Park Service followed Reclamation's less imaginative lead by referring to the lake as the Columbia River Reservoir. Reclamation suggested the change to Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake in April 1945, following the president's death. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes told Mrs. Roosevelt of the change. "The designation of this monument to the President's name has been done with a feeling of pride and yet with a deep sense of humility," he wrote, "recognizing that his greatest monument is in the hearts of the people." [15] |

Greider immediately began to prepare for the upcoming planning work at the reservoir area. He wanted two experienced planners, one with field experience in eastern Washington. They would need office space in either Ephrata or Coulee Dam, along with drafting materials, car and boat transportation, and the periodic use of a small survey crew. He estimated that these men, who probably could not start work until the weather warmed up in March, would need ten to twelve weeks in the field, followed by another six to eight weeks to prepare Master Plans. Greider appealed to Reclamation for help in meeting these needs. [16]

Help came not from Reclamation but from the CCC, which supplied Philip W. Kearney, Associate Landscape Architect, to the Park Service for the reservoir planning project. Kearney's appointment was approved on March 7, 1941, and he began work on site shortly thereafter. Despite urgent requests for additional help during the critical early period of work, apparently none was forthcoming from Washington, D.C., so Greider himself worked with Kearney for nearly two weeks in March. By mid-April, Kearney reported that he managed to have someone, probably from Reclamation, with him nearly half the time to assist him on site. [17]

The rigors of field work were the least of Kearney's concerns during his first six months on the job. Within a few weeks of coming to Coulee Dam, he was offered another position with Defense Housing in the Public Building Administration. Herbert Maier wired Kearney from the regional office, telling him that while it was Park Service policy not to object when a defense agency requested the services of an employee, that person did not have to accept the transfer. "We feel you are doing an excellent job on land use study and would very much regret [to] see this work interrupted or delayed," he wired. "Grand Coulee Land Use Study is a major undertaking which should bring considerable professional prestige to the one making it." [18] Kearney found that the proffered work would require an eventual transfer to Washington, D.C., and he decided to stay with the Park Service. "I hope that you will be successful in gaining me some stability in your department — at the desired grade," Kearney wrote to Greider. [19] He missed his family, who evidently lived in Seattle, and upon completion of the field work, he received permission to work on the final plans and drawings in Seattle. The regional office reminded him, however, that his official headquarters remained in Grand Coulee and thus he would receive no travel or per diem for this move. Within a few weeks of his return to Seattle, Kearney lost his job when the regional office terminated all CCC personnel. Kearney took the news "with a feeling of disappointment" that he was unable to have the satisfaction of finishing the job, and he forwarded his work to the San Francisco office for completion. [20]

|

| Bust of President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Visitor Arrival Center at Grand Coulee Dam, September 1957. The lake was named after the president following his death in 1945. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection (P 222 17 39522). |

The Park Service hired Kearney back in less than two weeks, but he approached the appointment with justifiable caution. Although he wanted to finish the project, he placed the welfare of his family first and noted that "the spring and summer was a distinct hardship for all of us." He refused to return to Coulee Dam, since that meant separation from his family, but he said that if the Park Service would let him complete the drawings in Seattle, he would be "willing to take the chance on the future but otherwise it is no dice." He had found the assignment interesting and appreciated the good treatment he received from Reclamation, but "the NPS has certainly kicked me around with very little consideration," Kearney wrote to Greider. [21] He was about to sign on with the Army Corps of Engineers when he received a wire from the Park Service confirming his appointment. "Now I will continue to hope that the NPS will need my services so that the career that I have chosen will continue uninterrupted." [22]

|

Crops are bumper and streams still high. So is

living.

--Phil [Kearney] to Claude [Greider], 12 July 1941. [23] |

During the spring and summer months of 1941, Kearney immersed himself in field work, getting to know the reservoir area well. His work was hampered by the difficult conditions he encountered. The water level was up to only 1,208 feet by late June, nearly inundating Kettle Falls and flooding the flats above Gifford and Inchelium. "For the first time the area assumes the character of a lake rather than a river," Kearney noted in his weekly report. Despite this rising water, it was still eighty feet below full pool, and Kearney was forced to examine potential swimming beaches and boat ramps at areas not yet touched by the lake's waters. [24]

The Committee on Problem No. 26 met in Olympia in May 1941 and listened to Kearney's report on his preliminary work at the reservoir. He discussed approaches to the reservoir, with the dam as the primary access point and the confluence of the Spokane and Columbia rivers as a secondary point. A new state highway ran north along the reservoir from this confluence, and he suggested that if Spokane interests developed a parkway from Riverside State Park to the mouth of the Spokane, it would bring tourists and boost recreational development on the reservoir. Kearney had concentrated his work on the three areas where there was enough federally owned land suitable for recreation: the dam, confluence of the Spokane and Columbia, and Kettle Falls. He recommended boat docks for all three areas but suggested that the most extensive development should occur at the confluence site due to its potential size and proximity to the Spokane urban population. In addition to the three major sites, he identified other sites suitable for picnicking, camping, boating, and summer home development. [25]

The potential for industrial development was considered part of the reservoir development from the beginning, so in addition to recreation sites, Kearney identified three primary areas for industrial use. The first extended from Spring Canyon to Plum and included four thousand acres acquired by the Columbia City Development Company. The second embraced the mouth of Hawk Creek where Lincoln Lumber Company operated its mill. The third encompassed the shore at the original Kettle Falls town site where up to two sawmills could be accommodated. "If proper land use principles are observed, industrial and recreational development in this district need not conflict," noted Kearney. [26] In an earlier report, however, he had cautioned that careful planning for industrial use was critical to ensure that "the industries do not make the area uninhabitable for those who are sensitive to their environment." [27] In addition to these three sites and the area north of Marcus, Kearney suggested that many industries would use the reservoir waters for transportation, necessitating coordination with recreational water use. After hearing Kearney's report, the committee decided not to make regulations for industrial use, but it stressed the need for standards to protect both public health and aesthetic values. After discussion, the members voted to designate fifteen miles of the south shore, starting at the dam, as primarily for industrial development. [28]

The committee also took up the matter of administration of the reservoir area. Reclamation reported many inquiries from individuals wanting to set up businesses on the lake, and the agency pushed for swift resolution of the question of future development and administration for the area. The committee considered several potential managers, including a private group ("not desirable"), Washington State Parks (no funding or personnel), Reclamation (also no funding or personnel to take on recreation in addition to irrigation), and a Columbia River Authority (not in existence). In the end, they reached the foregone conclusion: "The National Park Service has authority, has experience, personnel, has or can get funds, and its qualifications for the job are quite superior." Committee members saw other advantages to having the Park Service take over administration of the reservoir. Because the three agencies in charge of the area - the Park Service, Reclamation, and the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA, predecessor to the Bureau of Indian Affairs) - all were part of the Department of the Interior, they "could work out an agreement within a matter of a few days if the situation required it." The committee asked the Park Service to assume responsibility for the recreational development and administration of the Columbia River Reservoir Area, including developing Master Plans, constructing public facilities, supervising private development, cooperating with other governmental agencies, and providing funding for these responsibilities. In addition, the committee urged the Park Service to form an advisory committee to include representatives from the Problem No. 26 Committee. [29]

Reclamation was justifiably concerned about administration of the area as it continued to issue temporary licenses for both private and commercial use of the shore lands. Frank A. Banks recognized that such unplanned development was undesirable and could interfere with future public use. More worrisome were potential problems with commercial interests who spent money on private development and might later feel that they had vested rights in the land. Banks believed that if the Park Service refused to undertake development and administration of the reservoir, Reclamation needed to act quickly to find another agency to do the job. If necessary, he said that Reclamation could ask the Park Service to loan qualified advisors to the project. [30]

Instead, Reclamation offered limited support for Kearney's mapping and field surveys during the summer of 1941. The Park Service provided even less assistance. Aside from a brief two-day visit in early July from Thomas Vint, National Park Service Chief of Planning from Washington, D.C., and Ernest A. Davidson, Regional Chief of Planning, Kearney was basically on his own as the sole Park Service representative in the reservoir area. He ended his field work in late July. Following the interruptions in his employment, Kearney evidently finished the Land Use Study plans during the fall of 1941 in Seattle. The completed study was ready for review by the end of that year. After the success of the plans for the Columbia River Reservoir, the Park Service hoped to reassign the team of Kearney and Greider to work on the Central Valley Project in California, particularly the Shasta and Friant (Millerton) dam reservoirs. The men were not transferred, however. [31]

The Park Service did not immediately take over administrative responsibilities at the reservoir. The agency attempted to reach accord with Reclamation and the OIA, with representatives of all three signing an agreement in September 1941 (Greider signed for the Park Service). It never went into effect, however, because National Park Service Director Newton Drury wanted to wait for completed studies and a decision on the national significance of the reservoir. Reclamation was anxious to have the Park Service take charge of recreational development, however, so the two agencies signed a memorandum of agreement in July 1942 to have the Park Service assume general administrative and planning functions for the Columbia River Reservoir. Reclamation designated up to $10,000 to cover expenses for the first year, and the two agencies renewed this agreement annually until the Tri-Party Agreement was signed by Reclamation, Park Service, and OIA in 1946. [32]

While Park Service personnel proceeded with plans for recreational development at the new reservoir, agency officials continued to question the national significance of the proposed recreation area. Director Drury was hesitant to commit the Park Service to full involvement until he had a chance to visit the area and form his own opinion about its significance. If it were determined nationally significant, Drury hoped that Congress would recognize it with legislative authority. On the other hand, if it were determined less significant, the Park Service would not be the appropriate administrative agency. [33]

Not everyone within the Park Service agreed that the agency should take over the new reservoir area. In 1940, Regional Landscape Architect Ernest A. Davidson, who had lived in the Inland Northwest for thirty-one years, urged that the agency approach the new area with "great caution." Since the region had so many natural lakes, still largely undeveloped, he believed that campers and boaters would prefer scenic areas, like Lake Chelan, to the hot artificial lake behind Grand Coulee Dam. Greider refuted these claims, but within a year Davidson characterized part of the preliminary report on Problem No. 26, which compared the reservoir with other popular areas, as "propaganda . . . , incomplete or possibly one-sided." [34] Other Park Service officials urged civility and perspective. Raymond E. Hoyt, Chief of the Recreation Planning Division, decried the "unfortunate memorandum to Mr. Greider . . . which . . . tends to break down Service unity and the respect we should cherish for fellow workers opinions." After all, Hoyt reminded, "we are preparing a land use study and not an investigation of a potential national park." [35] Ironically, within a few years Davidson was sent to Coulee Dam to help with preliminary recreation planning. [36]

The release of Hoyt and Greider's report, "A Study of Land Use for Recreation Development of the Columbia River Reservoir Area above the Grand Coulee Dam, Washington," spurred further debate over the issue of national significance. The recreation area was definitely popular; in 1940, only Yellowstone National Park drew more visitors than Grand Coulee Dam, which attracted 325,000 tourists (100,000 more than Mount Rainier). Boulder Dam's 225,000 visitors in 1938 mushroomed to 800,000 three years later, the greatest growth for any recreation area in the west. One Park Service official believed that Grand Coulee Dam would continue to attract national tourists, but the small strip of federal land around the reservoir would attract regional residents only. "It is highly improbable that the so-called recreational resources of the Columbia Reservoir Area are of national significance," he concluded. [37] Drury, who became National Park Service Director in 1940, remained skeptical as well, partly because he thought the Park Service would need to acquire more land there in the future. "We had better try to define 'national significance,'" he cautioned late one night. "Don't let's fool ourselves about 'attendance' at Boulder Dam National Recreation Area." [38] Drury took a conservative approach to expansion of the National Park System. He believed in the concept of parks as the "crown jewels" of the country. "I was not particularly an advocate of adding areas of lesser caliber to the National Park System," he later recalled. [39]

The Director did not visit the area until July 1942 when he and Regional Director Owen A. Tomlinson were shown around the reservoir by Frank A. Banks and Phil Kearney. Drury was impressed with the beauty of the lake but remained concerned about the limited amount of public land. While the Director assured the group that he was keeping an open mind about the area, Banks later remarked to Kearney that "if this had been true he would not have been at such pains to remark on it." [40] Soon after the visit, Park Service officials edited a Reclamation press release about the Problem No. 26 report to "avoid any inference that the National Park Service is to be the permanent administrative agency for recreation on the Area," because Drury had not yet discussed the idea with Reclamation Commissioner Page. [41]

Kearney continued with his work on Master Plans during 1942. Reclamation assisted by providing detailed topographical drawings, while Park Service Regional Engineer Robert D. Waterhouse spent ten days in March helping Kearney with field examinations of potential recreation sites. The engineer recommended several months of intensive surveying to get data sufficient to meet Park Service standards. Because of this, Kearney realized that he would not be able to complete Master Plans that year and proposed doing less time-consuming preliminary plans instead. This would allow him time to advise Reclamation on boating permits, thus relieving pressure on that agency. [42]

The ten areas proposed for development were Rattlesnake Canyon near the dam (Crescent Bay), Spring Canyon, south approach to Keller Ferry, Hawk Creek, Fort Spokane, Gerome, Hunters, Kettle Falls, Barstow, and Sheep Creek. Kearney reported that some people from Spokane hoped that the old fort would be preserved as an historical site. He estimated that the brick buildings there needed just a small amount of work to "preserve them for all times," but he recommended removing some of the frame structures since they were not "of sufficient interest to warrant the great amount of work necessary for their preservation." Waterhouse found Kettle Falls a difficult area to design due to nearby houses, a new sawmill, the railroad, and abandoned roads. He and Kearney finally settled on an area for recreation "as far away from the commercial areas and the mess as possible." [44]

Prior to July 1942, Reclamation handled all permits for private development around the reservoir. The agency took a favorable stance toward industry and was fairly lenient in permitting businesses in the area. "You have to look out," Kearney found, since "private interests that mean business seem mighty attractive to the Bureau people." [45] For instance, a man under permit built a house at Fort Spokane where he planned to use some of the old WPA "shacks" for business operations. Kearney complained that the above-ground gasoline tanks there were unsightly. He was also concerned about a proposed magnesium smelter at Spring Canyon, even though Frank A. Banks assured him that they would find a site other than Hunters for loading ore. Developments at Kettle Falls were even more troubling since a sawmill had opened in a central location and loggers had cut timber around the bridges and mission site. When Kearney protested logging of federal lands, it "brought only mild surprise," but he hoped that the order to cease would be effective. Additional logging was going on between Hunters and the mouth of the Colville River, apparently on government lands. [46] Kearney predicted further problems and expressed his regret to Greider. "This is too bad as everyone here seemed quite willing to cooperate but cannot be expected to hold out indefinitely." [47]

Park Service operations at the reservoir were threatened by more distant events as well. Apparently Greider faced a potential call to service in the Air Corps on "short notice." Kearney worried that his colleague might be losing interest in the reservoir recreation project "with weightier things" on his mind, and he reassured him that the war might be over sooner than expected. [48] Later he mused about the war:

It still seems like fiddling — working on this job while things are in such a turmoil the world over but there is no place that I can see myself to better advantage wither [sic] for my personal welfare or for the good of the country. The situation seems to grow more and more confounding. I hope that the powers that be have a Master Plan. There is little evidence of the formulation of one in looking over the past events. [49]

Despite the turmoil of World War II, Park Service work at the reservoir area achieved a modicum of stability in 1942. Kearney moved with his family to Mason City in March. Funding became more predictable after the July 1942 interbureau agreement was signed providing the Park Service with $10,000 in Reclamation project funds to handle development and administration of the recreation area. After three years of working on preliminary plans for the reservoir, Claude Greider finally moved to the area at the end of the year, starting work as the Recreation Planner on December 26, 1942. Within a few months, the initial office staff was completed with the addition of Frances Fleischauer as clerk-typist. Greider reported to the regional office that Reclamation expected the Park Service "to assume rather broad authority" for planning and administration of the reservoir area, without depending on Reclamation staff. It believed that the area would be an important national recreation area (NRA), and Greider predicted, "Undoubtedly the best efforts of the Service will be put to the test over the next few years on this project." [50]

|

| View of Fort Spokane and the new bridge, 1942. The frame buildings near the bridge were removed before the Park Service gained administrative control of the property in 1960. The guardhouse, at right, remains. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3058). |

One test occurred in 1943 when Park Service and OIA officials disagreed over an issue at Sanpoil Bay. The Park Service identified the area near the old Keller town site as having good potential for recreational development. When Lincoln Lumber Company began using the site as a log dump in 1943, the Park Service, backed by the Colville Indian Agency, ordered the company to move its operations a short distance to the mouth of Manila Creek. Within a short time, however, the Colville Agency reneged, saying that the Keller site had greater value as a log dump than a campground. The Park Service, backed by Reclamation, stood firm, and the OIA joined the fray. Greider reiterated the Park Service policy of favoring industrial uses such as logging in areas where these interests were paramount. But, he continued, "It would not be considered in the best public interest to use valuable potential recreational sites for logging purposes when other sites of lesser recreational importance are available." The Park Service worried "that the loggers as a group have amply demonstrated that they have little if any regard for aesthetic or recreational values of the reservoir area." [51]

The disagreement soon escalated from a log dump to Indian rights. The OIA wanted to resolve the question of paramount use in one-quarter of the reservoir and wanted to take over management of freeboard lands (between high water and the 1,310 elevation) on the reservations. Greider suggested that the agency resented being left out of the interagency agreement between the Park Service and Reclamation. F. A. Gross, Superintendent of the Colville Agency, was less antagonistic than the OIA representative toward the Park Service operations, but he stood firm in what he viewed as best for the Indians. In particular, he did not want to restrict the potential development of the reservation timber resources, which he saw as the keystone of the Colville economy. He believed that unless the Indian Service or the tribes themselves spoke up for their interests, they would

be shoved into the background by more aggressive white interests along the reservoir shore. . . . When the Park Service officials speak of "the public interest" we fear that in their mind's eye they see primarily the motoring and boating public, the picnickers and the swimmers. [52]

Greider also stood firm in defense of the recreation area, and he told Lincoln Lumber Company that its use of the Sanpoil site would expire with its permit at the end of the year. It is unclear how the situation was finally resolved, but under the Tri-Party Agreement signed in 1946, the OIA specifically retained the right to issue and administer permits for log dumps within the Indian Zones at sites selected in consultation with the Park Service. The agreement likewise allowed the Park Service, in consultation with the OIA, to designate sites suitable for recreation in the Indian Zones. [53]

1944 Plans

The small Park Service staff continued its planning work during 1943 and 1944. Normally, the Branch of Plans and Designs produced the final site layouts and Master Plans for park units, but it did not become involved in the early planning for the Columbia River Reservoir since it was not yet a Park Service area and might not become one. Still, the Park Service felt an obligation under the interbureau agreement to give Reclamation workable development plans for each of the selected sites, especially since that agency was funding the Park Service work. Greider also believed that these detailed plans would be useful in case a "less experienced planning agency" were designated to take over recreation development. [54]

By mid-summer 1943, Greider and Kearney sent proposed layout plans for Spring Canyon and Hawk Creek to the regional office for comments, followed soon after by plans for additional areas. The comments they received were less about the specific designs than about the future of the recreation area itself. Herbert Maier, Acting Regional Director, worried that the plans should not be carried too far since the Park Service was not sure how much the general public would use the new reservoir. Greider disagreed. "Is it not true that this factor of future use is a problem in connection with any undeveloped area?" he asked. "It would seem that if exact knowledge of attendance and use is to be a prerequisite for park planning very little advance planning for any area would be justified." [55] He reminded the Regional Director that the Committee on Problem No. 26 had studied the recreational needs of the region and concluded that ultimately the area would need full development. While cautioning that the Committee was not party to the working agreement with Reclamation, Maier deferred to Greider for the final word on plans. [56]

|

| Log dump on the Sanpoil River, August 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Greider and Kearney finished the "General Report and Development Outline" for the Columbia River Reservoir in mid-1944. It not only outlined plans for specific areas but also laid out the Park Service approach to development, which was to maintain tight federal control of the entire reservoir area. The Problem No. 26 report had recommended that 80 percent of the shore lands were more valuable for recreation than any other purpose. Further study for the 1944 report showed that just 3 percent of the lands would be needed for recreation, but "in order to protect the full recreational values of this 3 percent, the preservation of at least 80 percent of the Area is essential." Greider and Kearney believed that federal standards were higher than those of private developers (whose standards were "only high enough to meet competition"), and thus the government needed to establish and enforce appropriate requirements for all phases of shoreline development, public and private. The plan proposed that the federal government construct and own all the basic facilities and utilities needed for public recreation on the reservoir, from boat docks and campgrounds to cabins and concession buildings. It also recommended that private resorts built on adjacent lands should be denied access to the reservoir unless these developments supplemented existing facilities and conformed to the overall program. [57]

Director Drury found the report excellent, but he requested a change in the section dealing with administration. He would not agree to have the Park Service assume jurisdiction and administration of the recreation lands at the reservoir, but he was willing to have the agency continue to advise Reclamation under the interbureau agreement. Reclamation also approved the report and reiterated its request to have the Park Service assume responsibility for the administration and development as soon as possible. After signing his approval of the report, Regional Director Maier penned the comment, "Thank God — that's over!" [58]

Agreements

Park Service Expenditures for FY1943:

|

Relief did not come swiftly for either Reclamation or the Park Service. An agreement to formalize the long-term administration of the entire reservoir area was pending clarification of Indian rights in the area. While awaiting final accord, the two agencies renewed the interbureau agreement described earlier, with Reclamation continuing to provide funding for Park Service operations. Banks defended this $10,000 appropriation in 1943, when emphasis was on winning the war. He argued that planning was needed to lay the groundwork for post-war development of the recreation area that would provide employment for returning servicemen. Reclamation funding enabled Phil Kearney to stay with the Park Service through the drafting of the "General Report and Development Outline." By April 1944, however, Banks decreed that Reclamation could not justify further expenditures for architectural plans until the agency in charge of recreational development and management had been selected. Banks thus requested that Kearney be transferred to Reclamation, leaving Greider as the primary Park Service employee until late October 1946 when he was joined by Robert D. Waterhouse, the Resident Engineer. Kearney had worked hard at maintaining good relations between the two agencies, and Greider benefited initially from this good will. [60]

The agreements between the Park Service and Reclamation were renewed several times as the agencies waited for a clear definition of Indian rights. Finally, in June 1945, the Solicitor set forth his interpretation of the 1940 Act for Acquisition of Indian Lands, including delineation of Indian rights to one-quarter of the area. Once this hurdle was crossed, the three Department of the Interior agencies negotiated the Tri-Party Agreement, signed on December 18, 1946. The Park Service, with so few employees, did not feel ready to assume full responsibility for the reservoir area, so it postponed this transfer of authority until July 1, 1947. [61]

Legislative Authority

LARO is one of only two units in the National Park System that lacks specific enabling legislation; the other is Curecanti National Recreation Area in Colorado. The Park Service gained authority at Lake Roosevelt in other ways, however. Initially, the Act of June 23, 1936 (49 Stat. 1894), authorized the Service to cooperate with other federal agencies, paving the way for the subsequent cooperative agreements with Reclamation at LARO. Congress passed more significant legislation with the Act of August 7, 1946 (Public Law 633), that authorized Park Service appropriations for "Administration, protection, improvement, and maintenance of areas, under the jurisdiction of other agencies of the Government, devoted to recreational use pursuant to cooperative agreements." [62]

A few months later, the Park Service, Reclamation, and OIA signed the Tri-Party Agreement to delineate administration of the recreation area. This occurred during the period when the National Park System excluded recreational areas, national parkways, and other non-traditional categories. Consequently, the agreement reflected this ambiguous relationship and stipulated that the Park Service's work at the recreational area

in no way implies that this Area is a part of, or intended to become a unit of, the National Park System or that the basic preservation policies under which the National Parks and Monuments are administered shall necessarily be applied in the planning, development, and management of the recreational resources of the Recreational Area. [63]

Park Service administration at LARO was strengthened on August 24, 1961, by a Deputy Solicitor's opinion concerning the Shadow Mountain NRA. It held that the Act of August 7, 1946, authorized the Park Service to apply its statutes and regulations to any recreation area, including LARO, that it administered through a cooperative agreement with Reclamation. Finally, the Act of August 18, 1970 (Public Law 91-383), amended the earlier Act of August 8, 1953, to define the National Park System as including "any area of land and water now or hereafter administered by the Secretary of the Interior through the National Park Service for park, monument, historic, parkway, recreational, or other purposes." This finally removed any lingering ambiguity about the status of NRAs such as LARO. The Act further stipulated that all authorities governing administration and protection of the National Park System applied to all units within the system, as long as they did not conflict with any specific provision. [64] These laws have provided the legislative authorization for LARO.

A recent District Court decision reinforced LARO's status within the National Park System. Torrison v. Baker et al., filed in 1997, disputed the Park Service's authority to require removal of previously permitted private docks within the NRA. In ruling against the plaintiffs, the Court wrote,

Since the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area is part of the National Park System, the Park Service must manage it in a manner "consistent with and founded in the purpose established by section 1 of this title, to the common benefit of all the people of the United States." 16 U.S.C. 1a-1 That purpose "is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." 16 U.S.C. 1 (emphasis added). [65]

Early Budgets and Staffing

Additional Congressional recognition of LARO came through line-item appropriations. Funding for work at the new reservoir came initially from Reclamation. Following the end of World War II, the agency increased its usual $10,000 request to $25,000 for FY1947. Greider hoped to step up the pace of recreation development and planning and requested an increase in personnel in May 1946 to include a recreation area supervisor, assistant supervisor, engineer, landscape architect or park ranger, clerk-typist, and clerk-stenographer. Banks supported the request, calling it a minimum, and suggested that Reclamation might be criticized if it did not provide sufficient recreation staff. The 1946 Tri-Party Agreement stipulated that Reclamation fund Park Service work at the reservoir. The agencies continued with this fiscal relationship through FY1948. All of the initial Reclamation funds came with strings attached and could be used only for administration and planning work. [66]

Despite the increases in funding, Greider was shorthanded much of the time during the early years. Following the transfer of Phil Kearney in 1944, Greider had primary responsibility for Park Service operations until late 1946, when he was joined by an engineer. The staff increased considerably in 1947 with the addition of a landscape architect, chief ranger, and clerk, but the work still exceeded available personnel. Greider complained about this situation, adding that he periodically had been forced to use engineer Robert Waterhouse for routine administrative matters, which cut into critical mapping and planning projects. "This staff is barely adequate to properly service the large number of current permits and applications," he reported. "It is wholly unable to function as an independent office in fiscal or personnel matters, or to adequately perform all desirable planning work." [67]

Reclamation equipment loaned to the Park

Service, October 1947:

|

The reservoir, known since April 1945 as Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake, and the adjacent shore lands, became Coulee Dam Recreational Area (LARO) with the Tri-Party Agreement. The signatory agencies discussed the name during negotiations in April 1946. They decided that the full name, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Lake National Recreation Area was "cumbersome" so Herbert Maier, Acting Regional Director, suggested that the area be named after the dam, which was the only one in the world while the country had innumerable Roosevelt lakes. Maier also opposed using the term "National" in the name since the Park Service did not have such a category. "We finally agreed upon 'Coulee Dam Recreational Area,'" Maier wrote. "The word 'Grand' was omitted since there is a Grand Coulee Area some miles below the Dam which is likely to become a state park." [69] The term national recreation area was applied to the reservoir by at least 1951 when the Park Service issued regulations governing use of the NRAs.

|

The projects carried on the current Coulee Dam

Recreational Area program total $1,694,200, so you can see what a long

road lies ahead of us before we can get up full speed.

--Claude E. Greider, LARO Superintendent, March 8, 1948 [70] |

Once freed from the budget restrictions imposed by Reclamation, the Park Service hoped to proceed with development of the new recreational area. The agency completed Master Plans in 1948 that spelled out development priorities. Greider estimated that it would take a major investment of nearly $1.7 million to get LARO up to full operations, ready to attract additional private investment in concession facilities. Despite the great need, Greider was a realist, and he hoped that LARO's small budget, including $30,000 for administration, protection, and maintenance and $12,500 for development, would not be cut. It was reduced, however, and LARO got $26,000 total in FY1949, with none for development — its first Congressional appropriation. [71]

Subsequent appropriations also fell far short of meeting LARO's needs. A similar situation occurred at other national park units across the country as the Park Service struggled to meet soaring attendance figures at parks where facilities had been neglected during the war years. By 1950, the Park Service had a backlog of work estimated at $500 million. Before it could make a dent in these needs, however, war broke out again, this time in Korea. National Park Service Director, Arthur E. Demaray, lamented that limited agency funding meant that there was not enough money to allocate large amounts to any one area, such as LARO, to complete major development work. "In fact," he wrote, "about all we can do with these limited funds is to take care of the most urgent needs on a Service-wide priority basis." While the funds spent at LARO were "not very impressive," they were typical of limited funds appropriated to the Park Service for several years. [72] Park Service budgets were cut again by 1952 and the following year the agency was subjected to a reduction in staff. [73]

|

As you know, there is likely to be a wide

difference between what we in the field think we can judiciously spend

and what Congress decides ought to be spent.

--Claude Greider, explaining the budget process to an interested party, 1948. [74] |

With federal budgets tight, Congress worked to balance competing demands. Washington Congressman Walt Horan was a staunch advocate of LARO and its plans for the area. He realized, however, that with large amounts of federal money pouring into Washington state for power and land development projects, he could not push for too much. "If we have to choose between recreational development and reclamation," he noted, "we would be forced to choose the latter." [75] He continued to push for funding, however, and LARO was one of just four areas nationwide to receive development funds during FY1950. He was unsure of additional money and explained to LARO supporters, "Unfortunately, we have a situation in which everybody wants to balance the budget in somebody else's back yard." [76]

Lack of funds to develop recreational facilities at LARO led to public relations problems for Greider and the Park Service. Money was just part of the problem, however. Another issue was the clash between the local population's desire for immediate development of any type and the Park Service's preference for orderly planning and development. Greider outlined the situation in 1947, advocating "a conservative and orderly program" and discouraging most recreational use until both the public and the resources could be properly protected. He planned to permit several concessions catering to boaters the following year. [77] Congressman Horan appreciated Greider's desire for careful planning, but he countered that "the demand for this development is becoming so strong and the Dam has been under construction for so many years that many visitors and residents in the area seem to feel this phase has been either neglected or unduly postponed." He urged looking into using private capital for some of the work. [78] Greider described Park Service plans for development of the new area to nearly 375 people at the Colville Chamber of Commerce meeting in December 1947. Those attending supported the Park Service and planned to lobby Congress to fund immediate development. [79]

Park Service Critics

After another year with little to show at the recreation area, the local mood turned angrier, fed by a small group of men in the Grand Coulee area who opposed the Park Service not only for its lack of development work but also for its attempt to restrict their use of the lake and shore lands. They charged that the Park Service was restricting permits on the lake and imposing such strict conditions on permittees that one man would have had to spend $20,000 for a dock, including $15,000 for surveys. Greider, who was seen as belligerent, needed to "get out from behind his miles and miles of plans and come down to earth" before the complainers would back his quest for funding. [80] Park Service officials defended their superintendent, and Greider decried "the aggressive campaign being staged by the Grand Coulee people to discredit the National Park Service program." [81]

The critics challenged both the lack of funding and how the Park Service spent what little money it received. The Spokane Chamber of Commerce urged rapid development to benefit private capital that was ready to invest in the region. It claimed that Lake Roosevelt's wonderful recreation potential was being held back by "the snail-like pace of development." [82] Another man looked at the three new houses built for Park Service employees and fumed at money being spent on administrative needs instead of public recreation. [83]

Many of the complaints centered around the perceived lack of industrial use of the reservoir area, even though all planning thus far had considered the needs of industries and agriculture. Indeed, Reclamation initially emphasized these non-recreational uses as an important part of the war effort and asked the Park Service to administer their permits, coordinating them with recreational plans for post-war development. The 1944 "General Report and Development Outline" provided guidelines for two categories of non-recreational development: essential public service utilities, such as municipal water systems and public ferries; and private industries including agriculture, logging, and mining. The report recommended that such uses be permitted where practical but never at the expense of the area's recreational values. By 1944, four sawmills and twenty log dumps operated along the lake shore, in addition to eighteen grazing leases, a passenger boat line, two freight lines, and two ferries. The 1946 Tri-Party Agreement gave further support to industrial uses by assigning the Park Service the function of issuing permits "for legitimate industrial and recreational purposes" along with agricultural and grazing leases on lands within the recreation area. As industrial use expanded after World War II, Greider and the LARO staff tried to satisfy demands for permits while protecting areas designated most important for future recreational use. For example, they redirected loggers away from the strip along Highway 25 as much as possible and tried to keep the Gifford area (across the river from Inchelium) entirely free of log dumps. By 1948, there were twenty-seven permitted uses related to logging, but the number of sites actually in use was probably much higher; Greider noted approximately forty log dumps used by fifteen companies or individuals. [84]

Despite these permitted industrial uses, a small vocal group continued to complain about the restrictive policies of the Park Service as well as what some saw as the uncooperative attitude of Superintendent Greider. One man suggested that the Park Service opposed private development in what was supposed to be a jointly operated area with 20 percent of the land set aside for industrial use. "If we are going to have those kind of regulations," he asked, "why not just call it a National Park?" [85] Greider defended his record, saying that by mid-1949 there were more than one hundred permits covering industrial uses on the lake, from log dumps and three sawmills to grazing and other agricultural uses. In addition, there was a tugboat transportation service and two railroad docks. Through his cooperation with industry, its value had grown to exceed several million dollars a year. Park Service planners continued to include industrial uses, such as sawmills, at LARO into the 1990s. The 1963 Master Plan even viewed such operations, especially tug boats, in a positive light: "We think these commercial uses add to the interest and enjoyment of the visitors and are to be considered an asset rather than an objectionable feature." [86]

Industrial uses eventually caused conflict between the Park Service and Reclamation at Lake Roosevelt. Reclamation, through all of its construction work at the dam, was inextricably bound with industry, and the dam itself was a major industrial site. In 1948, however, other Reclamation operations connected with the dam caused a serious inter-agency rift. Reclamation had closed its sawmill near the dam about a year earlier and planned to dismantle it, freeing the site for the long-awaited Park Service development of the South Marina. Then, without consulting the Park Service, Reclamation let a four-year contract for work on the pumping plant and feeder canal that included not only use of the sawmill but also construction of a concrete plant to be located at the proposed entrance to the South Marina, on the site of a planned Park Service headquarters building. A dismayed Greider told Reclamation officials that the contractor's use of this site would jeopardize Park Service plans for the whole area and would force the agency to revamp its six-year program. Frank A. Banks admitted his error and apologized to Greider. "It is regrettable that a misunderstanding has developed because our relations with you have been on such an amicable plane," he wrote, "largely due to your very cooperative and sympathetic efforts in discharging your responsibilities." He hoped that this incident would not delay plans for the South Marina. [87]

The issue was not easily resolved, however, and soon escalated to the regional level with both agencies. Park Service Regional Director Owen A. Tomlinson wrote to R. J. Newell, his Reclamation counterpart in Boise, to express concern for the situation and hope that it could be worked out without having to go higher. Within a short time, Newell telephoned Tomlinson and admitted "frankly" that the matter had been badly handled and vowed that there would be no such mistakes in the future. Despite this assurance, Tomlinson planned to ask the Director to talk with the Commissioner of Reclamation "so that definite instructions can be issued and every Bureau official will know [to] respect interbureau agreements with the Park Service." [88] Director Drury expressed his "regret and chagrin" that Reclamation did not follow the 1946 agreement but added, "Apparently the cement plant is now a fait accompli and nothing will be accomplished by crying over spilt milk." He asked if he could assure Tomlinson that the agreement would be followed in the future. The response from Michael W. Straus, Commissioner of Reclamation, was emphatic: "I can assure you that the Bureau of Reclamation will at all times attempt to carry out both the letter and the spirit of our inter-bureau agreement." [89]

Ironically, the Park Service gained some benefit from retaining industrial use at the South Marina site. Reclamation opened a rock quarry nearby as a source for riprap. In giving Park Service concurrence for this use, Greider asked Reclamation to set aside waste rock since LARO was looking for twenty thousand yards of material to improve the future boat dock area of the South Marina. Banks agreed to stockpile such material at the quarry site. Reclamation also agreed to locate the haul road so that it could eventually become an integral part of the proposed recreational plans. [90] The South Marina was not developed, however, and this was just the first of several cancellations or postponements of work at the site. Now known as Crescent Bay, the area still awaits development.

Rules and Regulations

The push for regulations provided another test for the Park Service as the agency sought to define its responsibilities and assert control over the lands and water of the newly established recreation area. The 1946 agreement required the Park Service to make and enforce rules and regulations concerning recreational use of the area as well as provide for the protection and conservation of resources. In a memo on July 11, 1947, the Secretary of the Interior set out departmental policy for the development and administration of recreational areas at reservoir sites. Greider was told to follow these guidelines while writing rules for LARO, using the regulations for Shasta Lake Recreational Area, approved in October 1947, as a guide. He completed his draft by September 1948. [91]

The draft rules and regulations for LARO dealt with all aspects of recreation. There was no fee for camping or swimming, but these activities were restricted to designated areas and common-sense rules, such as a prohibition on swimming without proper attire. Visitors could hunt, fish, and trap in accordance with applicable state and federal laws, but the superintendent could restrict these activities in areas of concentrated visitor use and could prohibit guns in certain areas. Boaters came under the most regulations and were the only ones required to pay a fee for use of the reservoir area. Annual permit costs ranged from $1 for a canoe or rowboat up to $10 for a boat over forty feet long. Boats were allowed to moor only at public docks or areas designated by the superintendent, and anyone planning a trip of more than four hours had to report destination and estimated time of return to a dock master. An initial legal review suggested that the Park Service might not have authority to regulate boat traffic on navigable waters, but Greider thought they could get around this since they controlled all the shore land and lake access and could essentially trade use of the land for reasonable control over boaters. [92]

Release of the draft regulations generated a mixed review. Much of Greider's concern centered on responses from the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club. The membership in 1949 seemed to support the need for some regulation, although a few members questioned the Park Service's authority to regulate boating on navigable waters. Greider was wary of the Yacht Club, however, since some of its more vocal members had been challenging other aspects of Park Service administration at LARO. Director Drury recognized by May 1949 that the proposed rules and regulations were "a major problem," and he urged that they be issued as soon as possible. [93] Greider did not want to rush, however, noting that "the importance of having complete control can not be over emphasized." [94]

|

| Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club picnic at Plum Point, July 1944. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection (12292-3). |

In the year following the release of Greider's draft regulations for LARO, the Park Service drafted a set of rules and regulations to govern all three National Recreational Areas: Lake Mead, Millerton Lake, and Lake Roosevelt. Greider found the new draft "wholly inadequate for this area" and suggested a rewrite. "Although we have already given the Washington Office our final advice on these regulations after two years of study of the problem," he groused, "we will prepare a new draft as soon as possible." [95] One of his particular criticisms concerned the addition of permit fees for the area, but he was overruled by the Regional Director who believed that Greider's concerns over collection difficulties and bad public relations would be overcome eventually. Greider countered that a greater problem was case law that held that all navigable waters in the country were to be considered common highways, free for all citizens to use. The Director, however, seemed less concerned with legal issues than public opinion, and he sided with Greider in ruling against imposition of fees. Frank A. Banks reviewed the draft regulations for Reclamation and complained that they did not recognize his agency's paramount rights in connection with the dam. He maintained that while Reclamation needed to keep the Park Service informed about its planned activities, its contractors could burn without permits, exceed weight limits on roads, and land boats wherever they needed. [96]

The new regulations met resistance from users of Lake Roosevelt. Initial comments from the Yacht Club were restrained. Greider had explained the changes to members and told them that the regulations would be issued by March 1950. Club members then requested that they be given a chance to comment prior to the new rules going into effect. The commodore described the club's divided opinion: some believed that new regulations were unnecessary since all the usual laws of navigation applied to the lake, while others did not object to sensible regulations to protect government lands. He stressed that members wanted to be reasonable and were not criticizing the Park Service. Although Department of Interior (DOI) officials believed they had fulfilled any need for public input, they decided to publish the proposed rules in the Federal Register to allow for additional comment. By late March 1950, Greider believed that the controversy had nearly run its course. He attributed the discord to a small group within the Yacht Club and suggested that other public groups were anxious to see the Park Service proceed with the more important work of developing the national recreation area. Greider emphasized the need to put the regulations into effect as soon as possible since "undoubtedly the long drawn out process of preparing them has permitted the dissenters to develop their case far beyond what the circumstances warrant." [97]

Despite Greider's wish for quick resolution, public comments became increasingly nasty. In general, people viewed negatively any restriction on their free use of the recreation area, whether it was the requirement for boat permits or the limitation of camping to designated areas. Congressman Walt Horan listened to his constituents and had harsh words for DOI's proposed regulations, calling many "unreasonably restrictive, some purely obnoxious and a few so downright silly as to be unenforceable." He approved proposed congressional legislation to give statutory authority for such rules, but he wanted to ensure that no regulation subject to punitive enforcement could be passed without a public hearing. Horan, interested in the development of the new NRA, warned that "the issuance and attempted enforcement of some of the regulations proposed in the current draft would raise a storm of protest so great as to retard indefinitely all hope of making this the first-class resort area it should become." [98]

The initially cooperative Yacht Club realized that the proposed regulations threatened free boating, and members began to question the Park Service's authority to restrict their pastime. The club had formed in February 1939 as the waters began rising behind Grand Coulee Dam. Its membership was primarily Reclamation employees, which strained relations between that agency and the Park Service. Greider believed that some Reclamation employees were unsympathetic toward the Park Service's responsibilities in managing reservoir areas, and he worried that such attitudes might cause the public to be concerned about cooperation between the two federal agencies. [99]

The controversy over regulations simmered for another year at LARO as the Park Service tinkered with the proposed rules and comments continued to trickle in. It heated up by early summer, following publication of the proposed regulations in the Federal Register on May 19, 1951. The Park Service intended to allow thirty days for comments before putting the new rules into effect. Once again, things did not go as planned. In an effort to quell the opposition, Superintendent Greider and "Red" Hill, Assistant Regional Director, held a public meeting at the Yacht Club on June 1. Approximately thirty-five people attended, representing a variety of sportsmen's groups. Greider began by giving some general information on the regulations, assuring the audience that the rules had been developed using suggestions from local residents as well as people who lived near the other two NRAs. The audience, however, was suspicious of any governmental control and concerned about what they saw as unnecessary restrictions. Frank A. Banks proposed a rewording of the camping section from prohibiting camping outside of campgrounds except in designated areas to permitting camping in all areas excepted those specifically closed by the superintendent. Greider seemed to agree. "Some feel it is written backwards," he admitted. "However, these are written by the best legal talent in the Department. That's the way they want it, to have the proper control where necessary." When people objected to the need for boat permits, Greider assured them that they would not be inconvenienced since permits would be readily available at main boating areas. [100]

Unquestionably, some of the animosity was aimed not just at the Park Service but also at Superintendent Greider personally. Clifford Koester, a regular critic from Coulee Dam, worried that "the Superintendent might get out of bed on the wrong side and it would be a tough day on the part of a lot of boat owners." Greider reminded Koester that the regulations were standardized and worked smoothly in other National Parks, as they would at LARO. Mr. Butler, commodore of the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club, was even more pointed: "Isn't it true, Mr. Greider, that any time that a group . . . figured that the Superintendent was getting out of hand they could get pretty fair recourse through the Regional Office?" he asked. "We could go to Mr. Hill and he would slap your ears down?" "I wouldn't be surprised," Greider responded. [101]

Comments increased, continuing to come in well after the June 19th deadline when the regulations were to take effect. While a few were unopposed, the majority had at least modest suggestions for change. The Park Service listened to the complaints and held up implementation to modify the regulations. For instance, it changed the camping section from a negative to a positive statement, permitting camping except where posted. Hunting and trapping restrictions were similarly altered. Boat permits were dropped and replaced with voluntary registration to aid in recovery of lost or stolen craft. The public may not have seen these changes immediately because protests escalated in the fall of 1951. Organizations began to call for cancellation of the Tri-Party Agreement and removal of Park Service authority at Lake Roosevelt. Some took their complaints to the Columbia Basin Commission (CBC) which, in turn, asked DOI to put the regulations on hold until the CBC and other groups had a chance to make their views known. Oscar Chapman, Secretary of the Interior, responded that the process had been going on for two years and he doubted that further public meetings would be of any benefit. He suggested an early meeting between the CBC and the Park Service to review the current draft since DOI wanted to issue the regulations soon. Instead, the CBC passed a resolution in early November asking DOI not to treat the area "as a national park, but as a sparsely inhabited recreational area," changing the regulations to give people "the greatest unrestricted use of the region." [102]

Before the end of 1951, Greider went to the regional office to rework the regulations with Superintendent Hugh Peyton from Millerton Lake NRA in California. National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth recommended approval in mid-May 1952, and several weeks later the Secretary of Interior issued the final regulations. "We believe . . . that every effort has been made to simplify them," he wrote, "and that an honest attempt has been made to meet . . . the objections received from the local people and organized groups interested in the Area." After living under the rules for a season, the Yacht Club's Commodore Butler, formerly a vocal critic, reassured Congressman Walt Horan that the regulations had been improved so that "the people of the area will be able to go along with them without feeling over-regulated to an irritating degree." [103]

Aftermath of the Regulations

Controversy

The controversy had run its course, but it left two legacies. The first was strained relations between Reclamation and the Park Service, still healing from the 1949 concrete plant controversy. While that conflict went to the heart of the interbureau agreement, the fight over regulations came down to personal relations between employees of the two agencies. Through the Yacht Club, many Reclamation employees had taken a stand against the regulations. Greider complained to Reclamation officials in mid-1951 about "the unusual activities of its employees" in opposing not only the rules but the Park Service's planning and development as well. He conceded that they had a right to their private opinions, but he emphasized that

when representatives of one government agency organize and carry on an intensive high-pressure public campaign . . . in which they misrepresent the purposes and policies of another agency with which they have a cooperative agreement, it is entirely another matter. [104]

A number of non-governmental people in the community had told Greider of being approached by Reclamation employees looking for support in their opposition to the Park Service. Greider finally met with the District Project Manager and his staff who agreed that Reclamation's propaganda campaign had gone to unjustifiable lengths. Reclamation agreed to draft a statement of support for the Park Service, and all believed that its release would reassure the public that the agency gave no official support to most of the complaints voiced by individual employees. [105]

The problem did not end there, however. The Park Service appeared vindictive later that fall when it requested transfer of the Yacht Club lease from Reclamation to Park Service control, less than two days after the club had taken a formal stand against the Park Service. The recently retired Frank A. Banks, former Reclamation supervising engineer, saw this move as retaliatory, and he also harshly criticized the Park Service for its lack of recreational improvements. He said that he had initially worked to attract the Park Service to the area but saw that the agency had done little to develop it or encourage recreational use. Instead, he believed the regulations and other rules discouraged and antagonized people, causing the Park Service's public relations to become "terrible." [106]

The second legacy from the fight over regulations led to the Park Service losing its bid to manage the Equalizing Reservoir, now known as Banks Lake. The reservoir formed after Reclamation constructed Dry Falls Dam near Coulee City and filled the formerly dry Grand Coulee with water from Lake Roosevelt. Water from the reservoir is used to irrigate the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project. The Park Service had studied this area in the 1930s for possible inclusion in the National Park System. While many believed it had unique geological and scenic values, a bill to establish the area as a national park received an unfavorable report in both 1918 and 1926, and National Park Service Director Horace Albright disapproved the idea in May 1933. Washington State acquired close to 470 acres at Dry Falls ca. 1922 for a state park. Construction of Grand Coulee Dam rekindled Park Service interest in the area, and a 1938 report suggested that the area south of the planned reservoir could be established as a national monument to showcase its outstanding geological features. The report also recommended that the Park Service consider the recreational development along both the Columbia River and the proposed reservoir to be formed in the North Coulee, with the combination of recreation and education offering "even greater appeal to the traveling public." [107]

Planning moved from the theoretical to the practical stage by the late 1940s as agencies and community groups tried to assess who could best manage the recreational aspects of the Equalizing Reservoir. The Grant County Recreation Committee, a subcommittee of the Grant County Chamber of Commerce, was concerned primarily with fast results. A secondary concern was development of a fishery program, and many on the committee felt that the state would be unable to produce results in a reasonable time. "Perhaps it is needless to say I did not say anything that would discourage . . . [this] line of reasoning," admitted Greider. [108] Before the end of the year, Washington State informed the Park Service that it would be unable to assume management and development of the reservoir, so Secretary of the Interior Oscar Chapman told both the Park Service and Reclamation to proceed with plans to add the reservoir to LARO. Five of the regional office staff spent several days the following spring conducting a preliminary study of the Equalizing Reservoir, and both agencies continued to plan for the Park Service to administer the new lake. [109]