|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 6:

Family Vacation Lake: Recreation Planning and Management

Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO) is primarily a place for people to play. A high proportion of its visitors has always been local residents, and in recent years more and more people are choosing to build homes adjacent to the recreation area boundary to take advantage of the many and varied opportunities for recreation on water and land. Recreation areas have sometimes been facetiously described within the National Park Service as "places to get wet," and even recent LARO Superintendents have viewed Lake Roosevelt in this way. [1]

LARO's recreational visitors focus on the water - on boating and swimming and on camping close to the lake shore during the short summer season. Land-based activities, too, have traditionally been aimed at outdoor fun. In the early years, playgrounds and horseshoe pitching areas were popular. Naturalists taught recreational skills such as snorkeling, and Disney movies were shown in the amphitheaters. Fishing has grown in popularity, and new opportunities such as rental houseboats and personal watercraft are increasingly popular with visitors.

Recreation planning and management at the national recreation area (NRA) have had to adapt to challenges such as low funding, jurisdictional disputes, and changing visitor activities over the decades.

|

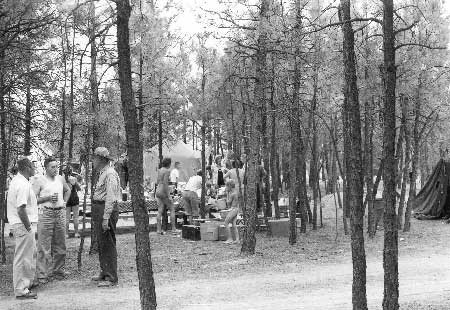

| Swim beach at Kettle Falls, 1965. Photo courtesy of Spokesman-Review archives. |

Who Visits Lake Roosevelt?

|

The people of no other country and no other age

had ever had anything like the leisure, the discretionary income, or the

recreational choices of the American people in mid-twentieth-century.

It was overwhelming. . . . Even though they might not always have used

this leisure to the best advantage, the American people had learned to

play.

-- Foster Rhea Dulles, History of Recreation, 1959 [2] |

Over the decades, LARO managers have initiated a number of studies to learn more about the "typical" visitor to Lake Roosevelt. What attracts people to the area, who are they, and what do they do once they arrive? The popularity of the nation's national recreation areas has grown significantly since the 1940s. By 1990, visits to NRAs accounted for 14 percent of total National Park System visits. [3]

After World War II, outdoor recreation increased tremendously nationwide, particularly water-based forms of recreation such as boating and water skiing. Causes of this growth included increases in the total population, per capita income, proportion of income spent on recreation, and leisure time, along with improved transportation. [4]

Visitation to Lake Roosevelt, however, was very light through the 1940s and the early 1950s, mostly because the reservoir was new, facilities were minimal, and area population was low. For example, in July of 1950 approximately 13,100 recreational visits were made to the NRA. About 90 percent of the use was by local people using simple temporary facilities constructed by the communities of Kettle Falls and Colville for picnicking and swimming. During the fall and winter months, hunters and float-plane pilots and passengers accounted for most of the recreational visits to Lake Roosevelt. Lake Roosevelt was simply overshadowed by Grand Coulee Dam, which was recording well over 300,000 visitors annually at that time. [5]

Visitation rose as Congress began to provide more funding for construction of visitor facilities. The area's population remained essentially rural, although in 1968 some 525,000 people lived within two hours of Lake Roosevelt. In the mid-1950s, Lake Roosevelt - promoted by the Park Service as the "Family Vacation Lake" - began to be discovered by travelers from outside the immediate area, sometimes by accident as they traveled through. In the north half, many of the visitors were from nearby Trail, British Columbia. In 1957, most of the visitors came from a fifty- to one hundred-mile radius, arriving on weekends by car. Day use remained primary; only 25 percent of LARO visitors remained more than one day. By 1962, over one thousand people per day were spending time at swim beaches. [6]

|

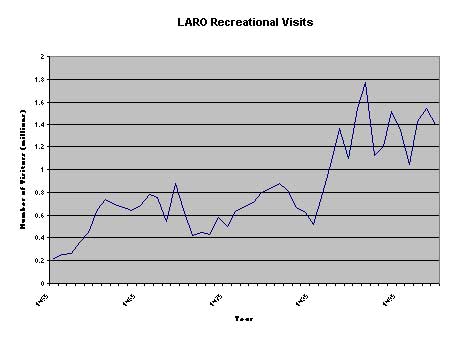

| LARO Recreational Visits (top), Grand Coulee Dam Visitors (bottom). |

|

Traveling through the Roosevelt Lake country,

in the northeast corner of Washington state, is enough to make a modern

motorist nervous. No view is blocked by a billboard, a hot dog stand or

a Kozy Kabin Kamp. He may cross two Indian reservations without a

chance to buy native beadwork from Japan. If he stops to eat lunch or

take a swim, nobody shows up to tell him he's on private property or to

collect for parking. Most travelers just aren't used to such treatment.

. . . As tourists discover Roosevelt Lake — and as the small towns

discover the tourist — the freshness of the country may disappear.

Meanwhile the sightseer finds himself in an anachronistic setting,

removed by many years from today's formal 'recreational area,' where he

can enjoy an uncluttered view and can stop to fish or camp where he

pleases.

-- Byron Fish, Ford Times, 1954 [7] |

LARO staff has tried to increase and regulate visitation through management actions such as construction of visitor facilities, removal of floating woody debris from the lake, and enforcement of regulations. In some years, visitation to LARO has been noticeably affected by events outside the control of the Park Service. Such events and circumstances include the 1962 Seattle World's Fair, opening of the highway through the North Cascades in 1973, Spokane Expo '74, eruption of Mt. St. Helens in 1980, value of the Canadian dollar, severe lake drawdowns, national gasoline shortages, improvement of the walleye fishery in the 1970s, overcrowding at other recreation facilities in eastern Washington, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) visitor facilities and attractions at Grand Coulee Dam, population shifts, and the weather.

In general, the majority of LARO's early visitors were day users, mostly family groups who lived in the vicinity of the lake. In 1962, park staff estimated that 10 percent of all visitors were in the area one hour or less, 50 percent spent one to four hours, 25 percent spent four to eight hours, and 15 percent spent one or more days within the recreation area. The peak period of use has always been from May to September. In more recent years, as the Spokane and Seattle-Tacoma populations have grown, a higher percentage of LARO visitation is drawn from these urban areas. [8]

A formal visitor survey conducted in 1978 through the University of Washington Cooperative Park Studies Unit helped LARO managers better understand the typical visitor. The study found that regional visitors chose to visit Lake Roosevelt in order to sightsee, visit Grand Coulee Dam, camp, and picnic. Family groups comprised 83 percent of the visitors. Most visitors had been to LARO six or more times and tended to visit the same site regularly. Thirty-two percent were from Spokane (and primarily used the central part of the recreation area), and 14 percent were local, but only 2.8 percent identified themselves as farmers or ranchers. About 13 percent were from Canada. At least half the campers and boaters fished during their visit. Only 15.7 percent camped in tents, and 17 percent of the boaters used non-power boats. In 1981, over half of LARO's visitors were children or teenagers, and 12 percent were Native American. [10]

|

Visitor Activities at LARO

|

A 1996 visitor use survey found similar patterns. Washington residents made up 74 percent of the visitors, with only about 7 percent from the United States outside of the Pacific Northwest. About 46 percent were repeat visitors. The most popular activities were camping, swimming, motor boating, and fishing, followed by family gatherings, picnicking, sightseeing, and water skiing. Nearly 75 percent of the use still occurs between June and September, and the late afternoon and evening hours are the busiest. [11]

Visitation to LARO has increased dramatically since the 1950s, when the Park Service first began to provide facilities and access roads along the shores of Lake Roosevelt. Keeping statistics on visitor use is important in every park unit: visitation figures identify trends that help in making management decisions such as planning visitor facilities and as justification for requests for budget increases.

At LARO, the lack of entrance gates makes obtaining accurate estimates of visitation difficult. From the early 1940s until 1955, LARO's visitation was estimated as a percentage (10 or 20 percent) of the visitation figures kept by Reclamation for Grand Coulee Dam. Since then, more accurate visitation figures have been obtained by counting vehicles (using a varying person-per-vehicle multiplier) combined with actual counts or estimates at places such as boat launches, concessionaire facilities, private docks and mooring buoys, and campgrounds. In recent years, reductions are made for nonrecreational users. The counting methods were modified in 1957, the early 1970s, and 1992. In 1988, traffic counters replaced the older tube counters park-wide. Park staff is "very, very confident," according to LARO Program Assistant Roberta Miller, that they are understating and not overstating the visitation to the recreation area. [12]

National Park Service Involvement in Reservoir

Recreation Planning

Beginning in the 1920s, the National Park Service played a leading role in recreational planning and development for state and local parks, many of which were later turned over to the states to manage. Because of the agency's experience with park planning during the 1930s, it often served as a consultant to new state park and recreation systems. [13]

In 1936, an important piece of legislation codified the cooperative relationship the Park Service had been enjoying with state parks informally since 1921 and through Emergency Conservation Work since 1933. The Park, Parkway, and Recreation Study Act of 1936 extended the Park Service's role in planning recreational areas and facilities at federal, state, and local levels throughout the country. As directed by the 1936 act, the Park Service in 1941 published a comprehensive study of public outdoor recreational facilities that outlined future needs for the nation, excluding areas already being managed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This plan was funded by Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) emergency conservation work appropriations, and it summarized the philosophy of New Deal recreational planning. The study noted the need for coordination among the federal agencies dealing with recreation and asserted that the Park Service was the logical agency to oversee the work. Four new kinds of national parks were being established or planned: national recreation areas, recreation demonstration areas ("submarginal lands" converted to recreational use, generally turned over to state or highway departments after development), national parkways, and national seashores. The 1936 act allowed the Park Service to plan for recreational uses of public lands in new areas such as these. [14]

The development of recreation facilities by the Park Service outside the traditional national parks became increasingly important to the agency in the 1930s. As the 1941 Park Service report on the nation's recreation facilities commented, "Artificial bodies of water in interesting settings, and man's ingenuity in creating them, have strong recreational appeal." Purists criticized Park Service involvement with recreational areas as a lowering of agency standards; they were uneasy about the consolidation of state and national park planning. Some also found it ironic that the Park Service was administering recreation at certain reservoirs while actively fighting dam proposals in areas where dams threatened national parks and monuments. The Park Service sidestepped the inherent contradictions in its actions by launching a new recreational program centered on large reservoirs. Some saw this expansion of recreational opportunities as a good way to relieve visitation pressure on the traditional national parks. [15]

The first recreational planning by the Park Service done in cooperation with Reclamation was the planning for Lake Mead, the reservoir created in Nevada and Arizona by Boulder Dam. In 1936, shortly after the dam was completed, Reclamation entered into a Memorandum of Agreement with the Park Service to create the Boulder Dam Recreational Area, the country's first NRA. The Park Service was also involved with recreational planning for reservoirs in the Colorado River basin and in other areas in the early 1940s. Between 1933 and 1964, five reservoir-based NRAs were added to the National Park System, including Boulder Dam (renamed Lake Mead in 1947) and Coulee Dam. The emphasis at these NRAs was on recreation, and consumptive use of park resources such as mining, hunting, and grazing were permitted. In 1997, even after some NRAs had been turned over to other agencies, the Park Service was managing twelve NRAs centered on large reservoirs. The reservoirs that the Park Service continued to manage, including Lake Roosevelt, were believed to have national rather than state or local significance. [16]

|

| Riding a surfboard on the rising waters behind Grand Coulee Dam, July 31, 1940. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection. |

Newton Drury, National Park Service Director from 1940-1951, believed that national parks should be limited to outstanding scenic landscapes; he was less than enthusiastic about the Park Service assuming responsibility for managing recreation on artificial lakes. He did not object to Lake Mead or Lake Roosevelt, though, because he felt the size of those two reservoirs made them significant to the nation as a whole. Just as World War II was ending, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Michael Straus asked Drury to examine the possibilities for Park Service management of smaller reservoirs expected to be created by future Reclamation dams. Drury openly objected to this concept, and in a 1952 speech he said that reservoirs like Lake Mead inevitably became dominated by local sportsmen and business interests, making them "local romping grounds." [17] Drury was overruled, however, by Straus and by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Ickes was attracted by the increased appropriations such recreation areas might bring the Park Service, and he also felt that NRAs would reduce the pressure on the system's other units. He and Straus felt Drury was attempting to back off from a serious responsibility of the Park Service and to retreat from the conflicts involved in recreation management. [18]

In the early 1940s, Park Service employees debated among themselves the merits of their agency's administration of Lake Roosevelt. Ernest Davidson, Regional Landscape Architect, for example, did not believe that the reservoir possessed national recreational significance. He argued that many natural lakes in the Spokane area were not being used to capacity and that Lake Roosevelt had much less recreational potential than Lake Mead. LARO's first Superintendent Claude Greider, on the other hand, remained "quite enthusiastic" about the possibilities of the area. He commented that the ultimate recreational use of the area was unknown, so planning should emphasize flexible development. [19]

Recreation Planning for Lake Roosevelt up to 1956

The Park Service became involved in planning for recreation on Lake Roosevelt in late 1939, when Reclamation organized the Joint Investigations of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project to provide an orderly program for the development and settlement of the project area. Problem No. 26 focused on the recreational development of Lake Roosevelt. The Park Service selected Claude Greider, a state supervisor with the agency based in Portland, Oregon, to head the committee. This was the start of Greider's fourteen-year involvement with Lake Roosevelt and the NRA that was eventually created around its shores. [20]

The committee's report, completed in April 1942, provided preliminary layouts of various recreational sites bordering the lake in order to facilitate rational coordination of private and public development. Ten sites were selected for priority development for general public use. General problems noted by the committee included the pollution of the Spokane River and the lack of shade trees at proposed development sites. [21]

For the next several years, Claude Greider and his small staff performed land use studies and formulated a development program for the NRA. Reclamation provided funds on an annual basis for the supervision of current uses. The Park Service was not allowed to initiate any development or protection of the area; its responsibilities were limited to administrative duties and planning. [22]

Finally, the decision as to which agency would manage Lake Roosevelt was made. In April 1946, representatives of the Park Service, Reclamation, and Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) drafted the tri-party interbureau agreement that designated the National Park Service as the principal administrative agency for the Lake Roosevelt area. The Secretary of the Interior approved this agreement December 18, 1946, and the area was designated Coulee Dam Recreational Area. Under this agreement, the Park Service assumed responsibility to plan for recreational facilities and arrange for their construction, operation, and maintenance; establish policies regarding the uses of the NRA; negotiate contracts for concessions; and designate (in consultation with the OIA) suitable recreation sites within the Indian Zones. The Park Service agreed to submit itemized cost estimates to Reclamation, which would advance the necessary funds as available. Reclamation agreed to provide facilities within the Reclamation Zone near Grand Coulee Dam for the Park Service to use in administering the area. [23]

Between 1941 and 1946, the years of temporary interbureau agreements and debates over which agency should manage recreation on Lake Roosevelt, a handful of Park Service employees worked on recreation planning for the reservoir in addition to administering its current uses. Philip W. Kearney, a landscape architect employed by the CCC, and Greider, with help from the Regional Office, completed a Master Plan for Lake Roosevelt in 1944 that superseded the report of the committee on Problem No. 26. [24]

Landscape park planning and design had matured in the late 1920s, and the Park Service hired many talented landscape architects during the 1930s. Master Plans represented an attempt to prepare plans for orderly development of an area. Individual layout plans for sites to be developed provided details concerning the location of individual features. Master Plans were intended to protect parks from excessive or poorly coordinated road construction and other development. They detailed multi-year programs of prioritized construction activity and were intended to be flexible to allow for changing conditions. Following this general program, Greider and Kearney classified the reservoir shore land according to zones for "best social and economic uses"; located sites for development of various resources; determined additional private lands for the federal government to acquire; prepared general layout plans for development of each recreational site; and coordinated all uses of the area. In 1943, Greider stated that the aim of the recreation program for Lake Roosevelt was to "provide wholesome recreation at the lowest possible cost to the individual." [25]

The Master Plan completed by Greider and Kearney in 1944 delineated a number of sites appropriate for recreational development. The report emphasized the need to provide a balanced program for the area as a whole, planning for full development but understanding that development would be made in phases only as required by public use. Post-war development, the report stated, should cover the estimated requirements for the first five years, guarding against over-development. The federal government (agency not yet determined) should develop and administer free public recreational facilities and boating. Private concessions should provide facilities for which a user fee was charged, such as boat docks, boat service facilities, concessionaire and lodge buildings, and cabin camps. [26] The plans prepared for this report generally provided the basis for the development of LARO that was finally funded in the 1950s.

The 1944 development plans for a number of sites included provision for one- and two-room cabins, shelter kitchens, softball fields, summer homes, and tennis courts, plus more traditional Park Service facilities such as swimming and picnicking areas, campgrounds, and restrooms. The "rustic" style of architecture popular during the 1930s was now seen as outmoded and too costly since the CCC program had been discontinued. The 1944 plans correlated nicely with recommendations made in Frank A. Waugh's 1935 book, Landscape Conservation: Planning for the Restoration, Conservation, and Utilization of Wild Lands for Parks and Forests. This work recommended that park structures should be in harmony with the setting, lacking in ornamentation, and arranged in clusters. Waugh stressed the need to plan for and select the best locations for a variety of sites, even if they were not to be developed initially. These included administrative, service, hotels and accommodations, water conservation and supply, sewage disposal, clubhouses, group campsites, tent campsites, playing fields, tennis courts, golf courses, bathing beaches, and fishing sites. [27]

|

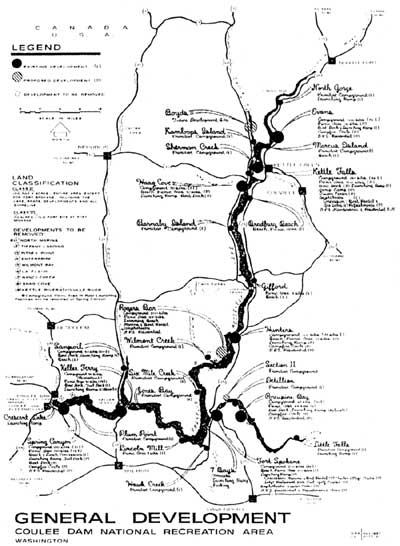

Proposed development sites, 1944 Master Plan:

1. Coulee Dam Marina (adjacent to Reclamation's Visitor Access Center, most needed, administrative headquarters) 2. Spring Canyon 3. Keller Ferry Park 4. Keller Wayside (only site on Colville Reservation) 5. Lincoln Canyon 6. Hawk Creek Harbor 7. Old Fort Spokane (important site, but river pollution will limit development) 8. Hunters Landing 9. Old Kettle Falls Park (on original townsite) 10. Marcus Island (major development) 11. Kettle River Camp 12. various remote overnight campsites for fishermen and boaters and also summer home sites -- Park Service, "Columbia River Reservoir Area," 1944 [28] |

Like other Park Service units established soon after World War II, LARO's earliest facilities were designed to be functional and relatively easy to maintain. For example, in 1954 Superintendent Hugh Peyton described the optimal comfort station design for Fort Spokane as having a concrete floor, pitched roof with composition roofing, steel windows, metal partitions and stall doors, and plumbing and storage space in the center between the men's and women's sections. [29]

Once rationing of gas and rubber was lifted at the end of the war, and as leisure time, disposable income, and mobility increased, millions of Americans took to the highways for vacations. Outdoor recreation grew tremendously popular. In 1941, swimming was the most popular outdoor sport in America, and boating was eighth. But on newly formed Lake Roosevelt, industrial uses dominated, especially uses related to the timber industry. In 1944, for example, only eight out of the sixty special-use permits granted by Greider's office were for recreation. For several years, the only public boating facilities on the reservoir were boat slips built by the Works Projects Administration in 1938 or 1939 and then leased by Reclamation to the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club. In 1940, a commercial outfit known as the Grand Coulee Navigation Company began providing passenger service on Lake Roosevelt, and soon Reclamation granted a few permits for boat fueling and fuel and mechanical service for seaplanes. [30]

By 1941, some fifty or sixty private "pleasure boats" were maintained on Lake Roosevelt (this number dropped dramatically, however, during the war). One of the influential promoters of boating on Lake Roosevelt was Reclamation engineer Frank Banks, whose thirty-four-foot cruiser was the largest pleasure craft on the lake. Many promoted the 328-mile waterway between Revelstoke, British Columbia, and Grand Coulee Dam, and in 1946 a Reclamation employee took eight days to paddle the full length in a homemade kayak. [31]

During the ten years between 1946, when the Park Service officially took over the administration of recreation on Lake Roosevelt, and 1956, when the Mission 66 program began, LARO staff concentrated on recreational planning, administering current uses, and constructing the first facilities for the public on the reservoir. Three districts were established: Coulee Dam, Fort Spokane, and Kettle Falls. By the late 1940s, a private float plane base that also provided storage and service for boats was established at the North Marina. This first public facility along the entire reservoir was located on land managed by Reclamation, not the Park Service. Initial Park Service planning concentrated on developments such as roads, water and sanitation systems, utilities, boating facilities, beaches, and picnic grounds at the major sites of Coulee Dam and vicinity, Fort Spokane, and Kettle Falls. NRA staff expected Kettle Falls to become the most important recreational site in the area, and they hoped for boating, float plane facilities, bathing, picnicking, camping, tourist cabins, and other facilities at that location. Secondary development sites included Keller Ferry, Sanpoil, Hunters, and North Gorge. Problems facing the Park Service, however, were significant. They included the poor fishery; woody debris floating on the lake and along the lakeshore (especially after the 1948 floods); pollution of the Spokane River, South Marina, Hawk Creek, and Colville River; and land acquisition (including much land needed at Fort Spokane). [32]

Private development by concessions began at LARO before the Park Service was able to begin construction projects. In fiscal year 1947, the Coulee Dam Amphibious Aircraft Company established a float plane and sightseeing boat operation; Grand Coulee Navigation Company initiated scheduled and chartered boat rides; and Stranger Creek Grange constructed a recreation site at Gifford. Over the next few years, concession facilities concentrated at North Marina, Fort Spokane, and Kettle Falls. [33]

Local groups did some development on their own, with Park Service approval. For example, the towns of Grand Coulee and Kettle Falls developed swim beach facilities in the 1940s, and the Red Cross provided swimming instruction at these and at the Reclamation beach at Coulee Dam. The Park Service tried to provide simple development such as hand pumps, beach improvements, pit toilets, tables and fireplaces, shade trees, and even boat launch ramps at some sites, often in cooperation with local groups such as the Wilbur Boat Club (Sanpoil campground), Wellpinit 4-H Club, and Greenwood Park Grange (Hunters). Superintendent Greider worried about public use of the area without adequate facilities and area regulations, but local communities successfully organized events such as a 1949 Fourth of July celebration at Kettle Falls that attracted seven thousand people for boat races and salmon barbecues. [34]

|

| Swimming class at North Marina, August 1946. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives 1346). |

Greider spent much of 1948 working on a new Master Plan for LARO that included drawings, a Development Outline, and proposals for construction projects for 1950-1951. The plans included a number of minor boat landings and picnic grounds at more remote sites to help meet the needs of area residents. Park Service Acting Director A. E. Demaray approved this plan in the fall of 1948. The proposed Park Service program for LARO involved spending $1.7 million over the next six years to develop Lake Roosevelt for recreation, with an anticipated $1 million in private funds expected to be invested by concessionaires. LARO staff felt that priority should go to facilities to make boating available, such as boat slips, fueling stations, docks, repair facilities, and the removal of hazardous floating debris on the lake. [35]

Development of a couple of the areas targeted for intensive development proved problematic early on in the planning process. One of these areas was South Marina (known today as Crescent Bay). In the late 1940s, this area was dropped from consideration as a development site because Reclamation needed to use it for a concrete manufacturing plant and because of dangerous slide conditions. Similarly, much of the development of Fort Spokane was reworked and then delayed because of new information on possible hazardous landslide potential and because the Park Service needed to acquire additional land there. [36]

The 1948 Master Plan contemplated a total of $2.226 million to be spent for physical improvements at LARO, of which $1.851 million was earmarked for the three districts' major development and minor areas. Development was planned to take place evenly throughout the area as the need for facilities was seen to be "equally acute" in each district. LARO, like other areas administered by the Park Service, prepared Project Construction Plans (PCPs) that allowed the Park Service to justify budget requests for development projects to the Bureau of the Budget and to Congress. At the end of 1949, the PCP priority list for LARO included three headquarters residences; an administrative building; dredging the channel at Kettle Falls to make it suitable for the concessionaire; a residence, warehouse, water and power system, sewer, beach and picnic area, and comfort stations at Kettle Falls; warehouse machine storage and partial water and sewer systems at Fort Spokane; a warehouse at headquarters; and a fence at North Marina. [37]

The planning for LARO's recreational development did not always go smoothly, partly because many offices and individuals were involved in the process. In 1954, the Acting Chief of the Western Office, Division of Design and Construction, commented to the Park Service Director that there had been "considerable disagreement on planning for Coulee Dam." [38] As an example, in 1954 and 1955 the Regional Office and LARO Superintendent Hugh Peyton conducted a prolonged argument over proposed layouts for Fort Spokane. Peyton wanted the approved plan revised, eliminating a motel that he did not believe likely to be built soon, so that some public service could be established that year. The Regional Office emphasized that any permanent development had to conform to the approved plan or be delayed until the Park Service Director approved a new drawing. Finally, in 1955 the Director approved the tenth version of the Fort Spokane drawing, one that eliminated both the proposed motel and concessionaire cabins and made other changes requested by Peyton. [39]

Once South Marina/Crescent Bay had been rejected for development, attention turned to Spring Canyon as the principal developed area at the lower end of Lake Roosevelt, an important site because Grand Coulee Dam received so much visitation. The Regional Office urged LARO to install a temporary boat ramp at Spring Canyon (along with picnic tables and fireplaces at North Marina) to relieve the public pressure. An access road to Spring Canyon was estimated to cost $123,000; Greider suggested that this expensive road be replaced with a gravel road because "it would not be good advertising to build a $123,000 road to Spring Canyon and then provide no means of using Spring Canyon beach at the end of this road." [40]

One of the challenging issues facing Greider was the acquisition of tracts of private lands that he believed "vital" for the recreational program proposed for Lake Roosevelt. In 1946, he recommended that the federal government acquire 1,600 to 1,700 acres. This included tracts totaling 325 acres along Highway 25 (Bissell to Evans) that might be developed in undesirable ways. The desired acreage also included land adjacent to sites proposed for intensive recreational development, about sixty acres to be donated for the Spring Canyon development, and about 370 acres in the Fort Spokane Military Reservation. In 1949, Reclamation began the process of acquiring some of the tracts considered essential for the development of key recreational areas. [41]

One land-acquisition case that took much time and effort to accomplish and resulted in difficulties in later years was the acquisition of some seventy acres in the Spring Canyon area. This land, located just a few miles above the dam, provided access to a proposed recreation site at Spring Canyon. The land was owned by the Columbia City Development Company, organized by residents of Grand Coulee to develop a city to replace the "shanty town" of Grand Coulee and to provide a site for a smelter at the mouth of Spring Canyon. The developers, seeing the advantage of a recreational site adjacent to the new town, in 1943 agreed to donate land to Reclamation contingent on future recreational development of the site. The Columbia City Development Company and Julius Johnson, who held principal interest in the company, signed an agreement giving the government five years to develop the recreational site. Some of the land to be donated was state land withdrawn for the Grand Coulee Dam project in 1934 and later sold by the state to the private company. The land donation did not actually take place until the summer of 1952, when Raymond and Vesta Johnson donated eighty-eight acres next to the Spring Canyon site. The land included a right-of-way for a two-mile entrance road and land needed for a beach, campground, and picnic facilities. This donation allowed the Park Service to request funds for the development of the site, and the campground, bathhouse, and swimming beach opened for visitors in June 1955. Almost twenty-six thousand people visited Spring Canyon that first summer. [42]

|

| Launching a boat at Kettle Falls, no date. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

|

I feel that everyone understands the urgency of

the current rearmament program and that much of the development we

considered so necessary a year ago should properly give way to this

greater emergency. We therefore feel it might be presumptious [sic] on

our part at this time to urge [Spokane Chamber of Commerce] efforts

toward appropriations for recreation developments for this area.

-- Claude E. Greider, LARO Superintendent, 1950 [45] |

The recreational development of LARO was severely hampered by budget restrictions. National Park Service appropriations were cut more than 50 percent during World War II. Funding levels remained low around the nation until 1950. In 1949, for example, the total Park Service operating budget was barely $14 million, and LARO at that time estimated that it needed some $2 million to complete enough development work to attract private capital to supply concession facilities. As Greider noted, "[the] little driblets of appropriations for this area such as we are to receive this year will accomplish exactly nothing." [43] Until 1949, all funds advanced to LARO were for administration purposes only, not for protection, development, or maintenance. Finally, in fiscal year 1950, LARO was appropriated $180,345, which allowed the Park Service to begin work on access roads, reservoir clean-up, and the construction of employee residences. It was one of only four recreation areas in the nation to receive such funding that year. [44]

|

LARO's existing buildings and buildings under contract, December 1953

Coulee Dam district: 3 residences, Coulee Dam garage, Coulee Dam paint storage building, Coulee Dam bath house, Spring Canyon comfort station, Spring Canyon Fort Spokane district: residence, Fort Spokane office-warehouse, Fort Spokane shop-garage, Fort Spokane 2 pit toilets, Fort Spokane residence, Gifford 2 pit toilets, Gifford 2 pit toilets, Keller wayside 2 pit toilets, Hawk Creek Kettle Falls district: shop-warehouse, Kettle Falls warehouse, Kettle Falls ranger station, Kettle Falls paint and oil building, Kettle Falls pump house, Kettle Falls bath house, Kettle Falls comfort station, Kettle Falls 6 pit toilets, Kettle Falls (beach, picnic area, campground) Concessionaire (Coulee Dam): residence duplex hangar boat repair shop -- Robert H. Coombs, LARO Acting Superintendent, 1953 [48] |

The first construction projects at LARO included work on approach roads to Kettle Falls, Fort Spokane, and North Marina and a boat launch ramp at Fort Spokane, all built in 1950 with the intention of enabling the Grand Coulee Navigation Company to install boat docks and to begin other developments. No money, however, was appropriated for fiscal year 1951 because of the Korean War. In 1952, on the principal that limited funds should be concentrated in one area to make it usable, all the development funds were spent at Kettle Falls, and the ranger office there was constructed. By 1956, the Spring Canyon and Kettle Falls beaches and campgrounds were essentially completed and landscaped, and a few small areas had minimum facilities (tables, fireplaces, and pit toilets), partly just to reserve the sites for public rather than private use. By 1955 Kettle Falls, for example, had a ranger station, bathhouse and comfort station, lawns, irrigation system, diving raft, and an improved beach. The picnic area at North Marina, built primarily for locals, was landscaped and outfitted with tables, fireplaces, and pit toilets. The development of Fort Spokane lagged behind somewhat because of the controversy over the layout for proposed development. [46]

LARO planners made provisions for permitting summer home sites and recreation sites for organized groups. The selection of summer home sites was delayed somewhat, partly to ensure that no sites were set aside that would have better served as campgrounds or other public use areas. In the 1940s it was decided that organized camping groups of "character building agencies," including statewide religious organizations, could obtain camping sites if their use did not conflict with general public use. In the early 1950s, ten sites at Sherman Creek and seventeen sites at Rickey Point, both in the Kettle Falls vicinity, were leased for summer cabins on a fee permit basis. [47]

One of Greider's major concerns during his tenure at LARO was Lake Roosevelt's poor fishery; he knew that improved fishing opportunities would greatly increase the area's recreational appeal. Rainbow trout could be caught at the northern end of the lake, but "scrap fish" such as carp, sucker, and squawfish predominated. The Washington Department of Game said it could not conduct a fisheries improvement program, but in 1947 Greider requested that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service undertake a limnological study of the reservoir to determine ways to improve sport fishing, and the agency complied. Meanwhile, many visitors to the area (including the family of Park Service Regional Director O. A. Tomlinson) stayed at fishing resorts at Twin Lakes on the Colville Reservation or fished at other small regional lakes. [49]

Development of Regulations to Govern the Use of LARO

During World War II, the Coast Guard established a patrol base on Lake Roosevelt in order to enforce motorboat and navigation regulations and to aid the federal guard in protecting the dam and other government property. By the end of 1942, the Coast Guard's forty men and four motorboats were doing regular patrols upriver to the mouth of the Spokane River, with occasional trips to Marcus and Northport (National Guard personnel did boat patrols for a few years after the war). The Coast Guard also installed directional lights as navigation aids. In 1949, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey completed a standard navigation chart of Lake Roosevelt. No markings, however, were placed on the water to designate the Indian Zones established by the 1945 Solicitor's Opinion. [50]

|

| Coast Guard patrol base about half a mile upstream from Grand Coulee Dam, December 1942. The former Camp Ferry barge served as quarters. Reclamation later leased this facility to the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives 559). |

In 1946, when the National Park Service was finally selected to manage recreation on Lake Roosevelt, no regulations had yet been established to govern the use of the lake. The only restrictions on small boats were those that normally applied on navigable inland rivers and lakes. Of particular concern to Superintendent Greider and his staff was the need for more stringent boating regulations. By the spring of 1946, before the Tri-Party Agreement had been approved, the office of the Park Service Director had asked the Regional Office to submit a draft of the rules and regulations for public use of the reservoir. On the national level, the Park Service started working on legislation that would give the Department of Interior authority to regulate recreational use of both navigable and non-navigable waters within recreation areas. [51]

Many public comments on the proposed regulations focused on particular aspects of recreational use of the reservoir. One of the questions most debated within the Park Service was whether or not to charge a fee for private boat permits. Greider supported permits but not an accompanying fee, partly because of the "difficult public relations situation" locally and because of the lack of rangers to enforce fee collection. The September 1948 draft regulations stated that a permit issued by the Superintendent, with a fee, would be required; the 1951 regulations mentioned a required free permit; the final regulations said that boat operators may register their boats with the Superintendent to aid in recovery of lost or stolen boats. This progression from quite restrictive to much less restrictive also occurred with other recreational issues, such as camping (from being allowed only in designated areas to anywhere except areas posted by Superintendent), and swimming (from being allowed only in designated areas to anywhere except in areas prohibited). The regulations were amended many times between 1948 and 1952. The Department of Interior finally approved and issued them on June 27, 1952. Claude Greider was transferred a year later. Hugh Peyton, former superintendent of the Millerton Lake NRA, replaced Greider at LARO. [52]

|

| Boaters from Wenatchee and Ellensburg starting off on a trip to the Arrow Lakes in British Columbia, June 1947. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection. |

During the sometimes acrimonious debate over the proposed regulations for LARO, the Park Service was also maneuvering to be selected as the managing agency for the twenty-seven-mile-long equalizing reservoir south of Grand Coulee Dam now known as Banks Lake. The Park Service proposed constructing recreation facilities and administering the recreational uses of the Upper Grand Coulee as an extension of LARO. The plan, predictably, met with strong opposition. Despite what Greider called a "propaganda campaign," until 1953 LARO staff assumed that the equalizing reservoir would become either a fourth ranger district of LARO or a separate NRA under Park Service administration. District headquarters were planned for the town of Coulee City. These plans were cancelled, however, in the spring of 1953. [53]

The Mission 66 Period, 1956-1966

The Park Service and LARO entered a new era in 1956 with the establishment of the Mission 66 program on the national level. This program resulted from the combination of delayed maintenance of Park Service facilities and increasing visitation to the parks throughout the country. Conrad Wirth, Park Service Director from 1951-1963, conceived of Mission 66 as a ten-year reinvestment and development program, timed to end with the agency's fiftieth anniversary in 1966. Congress responded generously with funding substantially increased over the annual Park Service budget. Wirth was a strong supporter of recreation in the national parks. Mission 66 projects included increased staffing, new interpretive facilities, campgrounds, roads, utilities, administrative and service buildings, restoration of historic buildings, employee residences, comfort stations, marina improvements, and visitor centers. The general emphasis was on improving the quality of the visitor's experience; Mission 66 emphasized use over preservation. [55]

|

In 1966 the Park Service would be celebrating

its fiftieth anniversary. What a God-given target to shoot for! Why

not produce a ten-year program, which would begin in 1956, aimed to

bring every park up to standard by 1966 — and call it MISSION 66? .

. . The entire organization went into action, regional office and park

staffs developing individual project plans and supplying cost estimates

for each park. Morale rose steadily as mouth-watering details were

passed along that old grapevine. In Washington, the park packages were

reviewed every weekend, until the total plan, containing the management

and budget requirements for each of 180 parks, had been completed. And

yet, the final tab seemed far beyond the limits of reality for those who

had been on short rations for so long. The total MISSION 66 program was

projected at $800 million. That the actual expenditure would pass $1

billion was not realized until much later.

-- William C. Everhart, The NPS, 1972 [54] |

Park structures of the early 1950s reflected modern architectural and landscape design and the use of modern construction materials such as concrete, glass, and steel. This type of design for Park Service buildings continued throughout the Mission 66 program. The Washington Office Division of Landscape Architecture commented that each area to be developed at LARO should be designed to have a "first class appearance," noting that "until this is done, Coulee Dam N.R.A. will remain neglected, rundown, and lost in the Master Plan files!" [56] In 1968, LARO staff proposed three architectural themes for the area, ones that were appropriate to the desert character of the southwest shoreline, the wooded northeast shoreline, and the historic features at Fort Spokane. [57]

As part of Mission 66 planning, every park prepared a Mission 66 prospectus, with assistance from the Regional Offices. The LARO prospectus, authored by Superintendent Hugh Peyton, emphasized two types of proposed development at LARO. One was the provision of facilities currently needed. The other was a program to set aside and save for future public use the Lake Roosevelt shoreline and recreational resources and to resist summer home sites, individual group development, and other such uses. He proposed many "pioneer" developments with minimum facilities to establish public rights to various sites. The overall program was quite ambitious: 132 new developed areas, varying from the "pioneer" or wayside areas with two table-fireplace units to campgrounds with 120 campsites, with a total of sixteen major areas. By 1963, more than halfway through the Mission 66 decade, LARO's facilities for visitors (not including those provided by concessionaires) consisted of fourteen bathhouses, twelve comfort stations, two picnic shelters, and seventy-six pit toilets. The most popular sites were Coulee Dam, Fort Spokane, Porcupine Bay, Kettle Falls, and Evans. [58]

|

One of the principal reasons for putting

minimum facilities at various spots along the lake in the form of minor

development areas is to "homestead" and keep these areas in public

ownership for future generations and to resist the eternal pressures of

groups and individuals to acquire Government land for private use, which

would exclude practically forever the vacationist who will need this so

desperately in the future. With the completion of MISSION 66 all of

these areas will receive proper attention and they will be preserved for

the use of future generations. The constant increase in the use of

present facilities in the area indicates that there is an urgent need

for the type of recreation which can be afforded by Coulee Dam National

Recreation Area.

-- Hugh Peyton, LARO Superintendent, 1957 [59] |

Peyton promoted LARO in the Mission 66 prospectus as the "Family Vacation Lake." He noted that NRA staff expected a tremendous increase in visitation during the coming decade. Their proposals for Mission 66 involved setting up low-cost minimum facilities to handle present and anticipated future needs. Peyton wrote, "Our area, in effect, is bypassing the normal slow gradual development, and passing from a pioneer stage into complete development." He continued, "We are confident that this quickening course is necessary and we welcome its coming." [60] LARO's Mission 66 prospectus was approved in April 1957. The total cost of proposed physical improvements, including roads, trails, buildings, and utilities, came to an optimistic $2,572,600, about 1/3 of which was earmarked for Fort Spokane. [61]

LARO never was flush with money, however. Even during the Mission 66 period, when Homer Robinson was Superintendent, much of the work was still done on a shoestring with much donated labor and scrounged materials. For example, all the LARO staff, plus Superintendent Robinson's wife, spent several Sundays at Keller Ferry clearing rocks and brush and trees to develop a small recreation area near the ferry landing. The ferryman allowed them to attach a pipe to his garden hose to provide water for the site. Next a pit toilet was built there, and then trees were planted. Sis Robinson felt the improvements were "VERY primitive," and LARO maintenance foreman Don Everts agreed that because little money was available, "we did it ourselves." Everts referred to some of these small campgrounds as "hatched," because he would fly over Lake Roosevelt and map the areas where people were already camping without facilities; the Park Service would then develop them. [62]

|

| Visitor facilities constructed at Keller Ferry, 1959. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Mission 66 and its special funding sources represented a turning point for LARO's development. Throughout the Mission 66 period (1956-1966), LARO made great progress in its visitor facilities, although nowhere near the proposed improvements. By 1968, the NRA had thirty campgrounds (nine of which were accessible only by boats), sixteen boat launching ramps, twenty-two fixed docks, and twelve developed swimming beaches (six with lifeguards). Many campgrounds had been expanded, and a few boat launch ramps had been built. Concessions, however, still played only a minor role at LARO. [63]

Recreation Management at LARO, 1966-1974

Park Service Regional Office and LARO staff prepared a new Master Plan for LARO in 1968. Like previous plans, it analyzed LARO's present and future needs and drew up general plans for development. The Superintendent prioritized the development projects, and the Regional Office assigned each proposal a regional priority. The Washington Office then consolidated the regional programs based on the nationwide needs of the Park Service. If Congress did not approve the funding request, then the programs were altered to fit available funds. The passage of the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970 led to greatly increased opportunities and requirements for public involvement in recreation planning. [64]

|

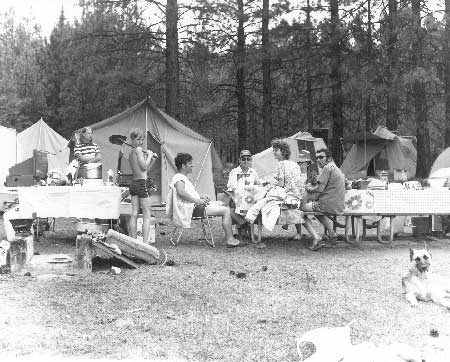

| Camping at Fort Spokane campground, July 1972. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

The Regional Office and even LARO staff still had difficulty singing the praises of the NRA during this period, however, although they did continue to emphasize the significance of the international waterway connecting Coulee Dam, Washington, with Revelstoke, British Columbia. The 1968 draft Master Plan, for example, contained this apologetic statement:

Surrounded as it is by a region outstanding for its lakes, rivers, mountains, forests, and wildlife, Roosevelt Lake suffers by comparison. . . . The lake's generally deep, cold, and murky water, enclosed by usually steep — often eroding — shores, relegates it to second choice after the numerous natural lakes of northeastern Washington and northern Idaho. This body of water is, nevertheless, notable for its length which makes it suitable for long-distance boat touring. [65]

After Mission 66, LARO staff worked with other agencies to accomplish some relatively minor development goals. For example, the Job Corps from Moses Lake installed a concrete launch ramp at Spring Canyon in the late 1960s as part of an expansion program at that site. Group campsites were established at Spring Canyon, Fort Spokane, and Kettle Falls (Locust Grove) in the late 1960s. Apprentices participating in a 1972 Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) training program built a portable entrance station for the Spring Canyon campground using Park Service plans in 1972, and Reclamation built a three-slip floating boathouse to serve both its needs and those of the Park Service. [66]

Ever since the early 1940s and the report of the committee on Problem No. 26, the Park Service had hoped to place all of the former military reservation of Fort Spokane under LARO administration. LARO staff found that the long process of transferring title to the land from the BIA to the Park Service created difficulties in planning for the recreational use of the area. The Solicitor's Office determined that Congressional approval was required for the transfer, and this was accomplished in 1960. The Park Service immediately announced plans to build a visitor center, bathhouse, maintenance shops, warehouses, equipment storage buildings, comfort station, and employee residence on the property, and to improve the road system and utilities. [67]

The construction of the third powerhouse by Reclamation in the late 1960s to increase the power-generating capacity of Grand Coulee Dam directly affected LARO operations. The Park Service had developed a campground and picnic area at North Marina in 1955 that was very popular with locals. It was located not far east of the Reclamation facilities near the dam that included a swimming beach and the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club facilities. Construction work for the new power plant required that the North Marina site be used as a fabrication site for heavy equipment. So, the Park Service decided to expand Spring Canyon in order to compensate for the loss of the North Marina developed site. Park Service operations at North Marina terminated in September 1967; North Marina (260 acres) was added to the Reclamation Zone in 1968; the Spring Canyon campground was enlarged in 1969; and plans were made to put in a boat ramp and boat dock. [68]

Another recreation-related development issue that LARO staff dealt with in the late 1960s was the establishment of a housing development known as Seven Bays between Hawk Creek and Miles that had two miles of common boundary with the NRA. LARO staff preferred having a plan in hand for the entire project before it issued permits to the developer, Win Self. LARO gave approval for the corporation to begin work on a beach and a small launch ramp with parking in 1968, with periodic inspections. When it was found that the launch ramp was not feasible in the chosen location, Self expanded his concept to include a concession-operated marina. [69]

|

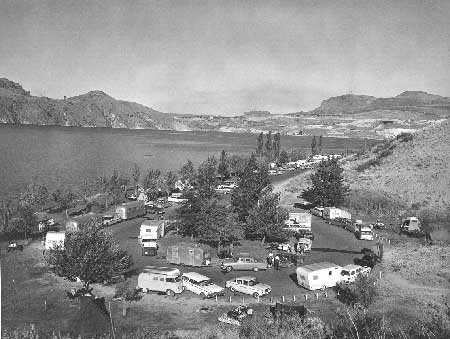

| North Marina Campground, 1962. Visitation to LARO increased this year because of travelers to the 1962 World's Fair. This campground was very popular until it closed in 1967 because Reclamation needed the site as a staging area for construction work. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Outdoor recreation planning continued on the national level in the 1960s, and some decisions affected the Park Service role in outdoor recreation. In 1958, Congress established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission. Its final report on the nation's outdoor recreational needs to the year 2000, published in 1962, resulted in a new Department of Interior bureau separate from the Park Service that was charged with overseeing a sweeping program to address the nation's recreation needs. The new Bureau of Outdoor Recreation's mandate essentially took away from the Park Service its responsibility for recreation planning, neglected in recent years, that had been given to it by the Parks, Parkway and Recreation Act of 1936. The 1962 report found that water was a focal point of outdoor recreation for Americans and that swimming, boating, and fishing were among the top ten activities. The Recreation Advisory Council, established in 1962, declared that the primary purpose of national recreation areas was outdoor recreation and that they should be areas "offering a quality of recreation experience which transcends that normally associated with areas provided by state and local governments." [70]

Reclamation contracted with Spokane architect Kenneth Brooks in 1967 to prepare a master environmental plan for the Grand Coulee Dam vicinity. The wide-ranging report included recommendations for sites managed by LARO, such as improvements at Spring Canyon and ferry cruises on Lake Roosevelt. Brooks also proposed fairly extensive recreational development on Banks Lake (including a water-taxi system to take families to campsites); two scenic highways offering vistas of Lake Roosevelt; a Columbia River Valley Parkway between Portland and the Canadian headwaters; and a week-long tour that included Fort Spokane, Grand Coulee Dam, water skiing on Hawk Creek Cove, boating on Lake Roosevelt, a camp-out on Banks Lake, and a helicopter trip to the Hanford facility. LARO Superintendent David Richie found Brooks' ideas exciting and commented in detail on the plan. He mentioned that a new "Grand Coulee Dam national park" could be created that would encompass "the world's greatest dam and its surrounding environment" and could be administered by Reclamation or a new agency. According to historian Paul Pitzer, however, Brooks' elaborate plan "briefly raised eyebrows and then quickly disappeared from view"; the proposed developments were far too extensive to be practical. Most of the changes made as a result of the plan were minor, such as landscaping and beautification projects. [71]

All of the foregoing issues of the 1960s and early 1970s paled before the very complex and contentious issue of tribal rights on the waters of Lake Roosevelt and on the freeboard lands within the two reservations. Tribal jurisdiction over campgrounds within the Indian Zones and hunting, fishing, and boating on Lake Roosevelt came to the forefront during this period as an important issue that needed resolution. [72]

In June 1974, the Solicitor's Office issued an opinion on the boundaries and status of title to lands within the two Indian Zones created by the 1945 Solicitor's Opinion. This opinion had far-reaching implications for LARO, as it held that the two tribes had reserved rights preserved by Congress in the Act of 1940 and that these rights were exclusive of any rights of non-Indians there. Thus, each tribe now had the legal authority to regulate hunting, fishing, and boating by non-Indians in its own Indian Zone. The 1974 Solicitor's Opinion also effectively nullified parts of the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement. [73]

The following month, the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) and the Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI) agreed to enforce their fishing ordinances in the existing Indian Zones but to leave regulation of boating, water skiing, and swimming to the Park Service. The enforcement of the fishing regulations proved difficult, however, because the Indian Zones had never been marked by buoys or signs, so the public had difficulty determining their boundaries. The Indian Zones consisted of approximately 45% of the land and water of LARO. In 1982, the CCT made arrangements with the state for reciprocal licensing so that the general public did not have to buy tribal fishing licenses to fish in the waters under their jurisdiction. [74]

Recreation Management at LARO, 1975-1998

On May 19, 1975, the Park Service transferred the responsibility for the operation of five campgrounds within the Indian Zones, giving the CCT responsibility for Sanpoil, Three Mile, Wilmont, and Barnaby Island and the STI responsibility for Pierre. The transfer was made pursuant to a provision of the Tri-Party Agreement of 1946 that authorized such transfers to the state or to other political subdivision. Some LARO employees resented the takeover because they perceived the tribes as not maintaining the facilities to Park Service standards. That first summer, the STI charged a fee at Pierre and visitation dropped considerably. Sanpoil had the most facilities, including a comfort station, launch ramp, potable water, and fifteen sites with tables and fireplaces, a playground, and a small boat pier. The others ranged from having no facilities (Three Mile) to being well equipped (Pierre). Sanpoil campground is still maintained, but the other four transferred from LARO were not being maintained as of 1987. Both tribes have added new campgrounds within the Reservation Zone, however. [75]

During the 1970s and 1980s, LARO recreation planners faced several new challenges, including vastly increased visitation to Lake Roosevelt. Between 1985 and 1989, visitation to the NRA increased by 171 percent (visitation to Park Service units nationwide only increased 7 percent during this period). The increased use during this period was due to gasoline shortages that caused people to travel closer to home, the availability of rental houseboats on the lake, and the lake's growing reputation as an excellent fishery. Overcrowding at campgrounds on weekends became a common problem at several of the larger developed sites. The most popular campground was Porcupine Bay, and Keller Ferry campground experienced the most overcrowding. [77]

|

It is hard not to reach the conclusion that at

Coulee Dam National Recreation Area we are, in effect, operating a

lake-oriented network of local "parks." Indeed, facilities at a number

of sites appear to be of the "county park" variety and one is led to

question whether we might be overdeveloped at a number of recreation

sites. Superintendent Dunmire and I discussed this question, i.e.,

"should the National Park Service, as it does at Coulee Dam, provide at

national taxpayer expense such amenities as 'changing houses' for

bathers, broad expanses of well groomed lawns and overnight docking

facilities for boaters?" Such questions, we concluded, were points that

specifically need to be surfaced and dealt with in the development of a

general management plan.

-- Temple A. Reynolds, Park Service Associate Regional Director, 1978 [76] |

The CCT in 1988 established a Tribal Parks Department to serve the recreating public and to protect the resources of the reservation. The following year, the tribes proposed building campgrounds with boat launch ramps at Inchelium Ferry and Sanpoil Bay. In the late 1970s, the STI developed the Silpinpitkin campground on Lake Roosevelt for tribal use only. The STI's tribal park rangers work in the natural resources department. [78]

Back in 1967, LARO staff had begun developing construction standards and policies for community docks to replace individual docks provided for under individual permits. The Park Service felt that private facilities such as docks on government land near the shoreline created the impression that public use within those areas was not welcome. As Kelly Cash, LARO Assistant Superintendent, commented in 1986, "It simply is not fair to the visiting public to let their shoreline be nibbled away by private development." [79] Over the years, many individual docks whose permits had expired were removed from the lakeshore by their owners and replaced by community docks. [80]

In the 1970s, LARO tried to meet the increasing pressure of boaters on Lake Roosevelt by widening or building new boat launch ramps. The Denver Service Center was responsible for the design and planning of the ramps, and Reclamation for their construction. LARO received $730,000 under the federal Land Heritage Program for ca. 150 floating facilities, including concessionaire fueling facilities, docks, moorage, gangways, and swim platforms. [81]

Work on expanding LARO's floating facilities continued in the 1980s. To provide boating facilities that were usable during summer drawdowns of Lake Roosevelt, Reclamation and Park Service worked out an agreement to modify existing boat launch ramps and other facilities to function when the reservoir was drawn down well below 1,290 feet. During this period, LARO also added a number of boat-in campgrounds to the recreation area (most of the earlier ones had been located within the Indian Zones). Since the 1980s, boaters have been allowed to camp wherever they like if they have a portable toilet on board. [82]

The negotiations over the division of management responsibilities for Lake Roosevelt were essentially resolved by the April 5, 1990, signing of the Lake Roosevelt Cooperative Management Agreement (the Multi-Party Agreement). This new agreement confirmed the Colville and Spokane tribes' management authority over the reservoir and related lands within the boundaries of their respective reservations. It required the five signatory parties — Park Service, Reclamation, BIA, and the two tribes - to coordinate their management efforts and to standardize their policies as much as possible. The agreement created the Lake Roosevelt Coordinating Committee to facilitate coordination of such issues as visitor safety and law enforcement, concessions, and radio communications. [83]

In essence, the 1990 agreement reaffirmed the status quo since 1974, that the tribes managed the lands and waters bordering their reservations and the Park Service managed the rest of the federally owned land and water (except for the land managed by Reclamation). Since 1990, the Park Service has managed approximately 61 percent of the land and 58 percent of the water in the management area. The tribes and the Park Service occasionally work together on recreational projects. For example, there are current plans for joint construction of a launch ramp on the Sanpoil River. [84]

By 1988, LARO's recreational facilities were rather extensive. They included twenty-seven campgrounds, twenty-nine picnic areas, fourteen launch ramps, ten swim beaches, and five concession operations. A Concession Management Plan for Lake Roosevelt was prepared by the tribes, Park Service, Reclamation, and BIA and approved in 1991. But overcrowding of campgrounds, parking lots, and other facilities continued to be a pressing issue for LARO management throughout the 1990s, along with the lack of some needed facilities such as a marina on the south end of the lake or facilities to serve the residents of new communities along the lake. [85]

The 1978 National Parks and Recreation Act contained a provision requiring the Park Service to prepare and revise General Management Plans (GMPs) for each unit. The GMP prepared for LARO in 1980 proposed four alternatives for managing the NRA. Plans for each major developed area included various visitor and administrative facilities. The selected alternative allowed for expanding current developments as the need arose while preserving the "low key atmosphere" desired by visitors. All new and improved facilities were to be fully accessible to handicapped visitors. Low-energy forms of recreation would be emphasized, and moderate upgrading and expansion at major developed areas was planned. The Indian Zones were not included in the recommendations in response to CCT comments that the GMP should not be prepared until the management roles of the tribes and various agencies had been clarified consistent with the 1974 Solicitor's Opinion. [86]

In 1998, LARO prepared a new GMP to replace the first one approved in 1980. The preferred alternative, approved January 2000, called for increasing the capacity of existing facilities where feasible and redirecting some visitation to less-used areas. Proposed management changes included allowing community launch ramps and docks where there is a need for local access to Lake Roosevelt (these would be available to the public, unlike existing community docks); increasing "protected waters" areas for canoeing; developing concession facilities at Crescent Bay and Hunters; and establishing a deep-water moorage facility in the Kettle Falls area. LARO was zoned into new management areas according to intensity of use, with each zone to be managed according to its character. [87]

One of the issues addressed in the 1998 draft GMP was the need to expand the Kettle Falls marina because of increased visitor use and impacts on the concessionaire due to the low drawdown levels. The Park Service examined deepening the existing harbor at Kettle Falls and/or establishing a new location for deep-water marina facilities in that area (Lion's Island and Colville Flats were both considered and rejected in the 1990s because of environmental impacts and highway access issues). The need to dredge the Kettle Falls harbor had been recognized as early as the 1940s; it was dredged in 1951 and then again in 1985 and 1990 in cooperation with the Washington State Department of Transportation. [88]

In 2000, the Park Service banned personal watercraft such as Jet Skis at all but ten of its units. LARO is one of the NRAs where they are still allowed. During the scoping for the 1998 GMP, many members of the public expressed concern about the noise of the watercraft and the perceptions of their increasingly irresponsible use on Lake Roosevelt. LARO and the tribes agreed to monitor the situation closely and to establish regulations if necessary. [89]

The 1990 Special Park Use Management Plan addressed Park Service concerns that public lands along Lake Roosevelt were being privatized. The plan directed LARO to begin phasing out special uses that were found to be in conflict with applicable laws and Park Service management policies, including private lawns, private docks, and grazing and agricultural permits. The phasing out of livestock grazing permits (not yet completed) has had a positive impact on public recreation in the NRA. LARO staff also began building fences around a few of the popular developed areas to keep out livestock. [90]

In the 1990s, as more and more people began to build homes near Lake Roosevelt, the Park Service recognized that previous management plans did not provide sufficient facilities for people living along the lake. Also, between 1985 and 1991, years in which LARO visitation and boat launchings on Lake Roosevelt increased dramatically, only one new launch ramp had been constructed at LARO. The Park Service contended that lake access suffered during summer drawdowns. LARO and BPA staff prepared documentation supporting their request for funds to build new launch ramps and to extend existing ramps on Lake Roosevelt, working with Congressman Foley's office. Beginning in 1991, LARO received special Congressional appropriations totaling $1.9 million to build six new boat ramps at locations determined through public input and to retrofit and expand nine existing ramps so they could be used at lower lake levels. These new and improved facilities, built 1991-1993, allowed adjacent landowners to access the lake more conveniently, and they also helped relieve crowding at some of the developed areas. Today, some of LARO's multi-lane boat ramps handle as many as 125 launches per day during the busy season. [91]

A partnership that LARO hoped would be a "model for the future" was developed in 1991 to build a boat ramp and parking area at the Lincoln Mill site near Fort Spokane. The construction was funded by Lincoln County, the Park Service, the Interagency Committee for Outdoor Recreation, and private sources, and the Park Service agreed to maintain and operate the ramp. [92]

By 1998, LARO had 22 boat launch ramps (8 more than in 1988). Other visitor facilities included twenty-eight campgrounds (ten of which were boat-in only) with 640 individual sites plus several group campsites and three concession-operated marinas that provided moorage, boat rentals, fuel, supplies, sanitary facilities, and other services. The two tribes operate ten campgrounds along the shores of Lake Roosevelt. [93]

User Fees

Because of the many access roads to Lake Roosevelt, it has never been feasible to collect park entrance fees at LARO. User fees, however, can be charged for the use of specific facilities such as campgrounds and boat launch ramps. During the 1940s, LARO Superintendent Claude Greider argued against instituting boat permit fees at the NRA, and this was confirmed in the regulations approved in 1952 for Lake Mead, Millerton Lake, and Coulee Dam national recreation areas. Fees for government-operated campgrounds, however, were prohibited in the National Park System until 1965 and were not systematically instituted until 1970. The money collected from these fees was placed in the general treasury and made subject to congressional appropriation. The funds did not return to the parks in which they were generated, although after 1972 they did at least return to the Park Service. The use of the collected fees was authorized for resource protection, interpretation, research, and maintenance activities related to resource protection. [94]

The institution of campground fees within the Park Service was initiated by the 1962 Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission report, which called for user fees for federal recreational facilities such as campgrounds. The report led to bills that contained authority for federal agencies such as the Park Service to set entrance and user fees, and this policy became effective in 1965 with the passage of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act. By 1968, earlier than most other Park Service units, LARO was charging a camping fee at its largest and most developed sites (Spring Canyon, Fort Spokane, Porcupine Bay, Kettle Falls, and Evans). Its $2 camping fee was higher than the local Forest Service fee of $1, and some members of the public complained about the discrepancy. By the late 1970s, LARO was collecting some $30,000 each year in camping fees. In 1976, for example, the NRA collected about $5 for every $1 spent in fee collection. In that year, LARO staff increased the fee to $3 per night, numbered campground sites, and set up registration bulletin boards. [95]

During the 1980s, LARO continued to improve its fee collection system and to increase the camping fees. In 1982, the fee jumped to $5 per night for sites in the six most highly developed campgrounds. Despite local controversy, fees were instituted at Marcus Island campground in 1987. In 1989, a courier system was established to provide better control over the counting of collected funds, and soon a local bank was counting the monies. In 1989, over $130,000 was collected in user fees. [96]

The fee collection program at LARO changed significantly in 1994 and 1995 because of Congressional legislation mandating the collection of fees for some facilities and services that previously had been free. As a result, LARO began charging fees at all seventeen vehicle campgrounds. Beginning in June 1995, a boat launch fee was charged to the general public. Tribal members were exempt from this charge at all LARO ramps, as were Lincoln County taxpayers through 2005 for the ramp they had helped fund. The fees charged were based on fees for similar facilities at Washington state parks and private sites. LARO was the first Park Service unit to enforce the charging of fees for boat launch ramps, and the NRA received little public support for this action. The campground and boat launch fees collected in 1995 increased considerably over previous years to more than $311,000. Today, a fee is charged at all the launch ramps managed by the Park Service at LARO. The two tribal ramps at Inchelium and Two Rivers do not charge (the tribes charge for camping only). [97]

The Park Service instituted a three-year Fee Demonstration Program in 1996. LARO was selected to participate. Under the program, 80 percent of the revenues collected were returned to LARO for use on approved projects. The remaining 20 percent were distributed Servicewide. This program provided significant funds to LARO. Projects funded by the program have included solar lighting at various visitor facilities; accessible restrooms; launch ramp extensions; and shore anchor and courtesy dock improvements. In general, the monies fund minor construction, rehabilitation, and cyclic maintenance projects. [98]

User fees are sometimes used to distribute visitors throughout a park. Another method of controlling crowding at campgrounds is the reservation system. The Park Service instituted a campground reservation system in 1973. By the late 1980s, group campsites at LARO could be reserved. The reservation system has not yet been extended to individual campsites, although this may be considered in the future to reduce problems with overcrowding at popular areas. Other measures may include installing signs at key junctions along the highways telling visitors that certain campgrounds are full and offering additional information. The CCT instituted a reservation system for non-member camping at four campgrounds on Lake Roosevelt - Inchelium Area AA Camp and the Keller Park, Sanpoil Bay, and Wilmont Creek campgrounds - and they also began charging a user fee for camping throughout their reservation, including sites along the shores of Lake Roosevelt. [99]

Visitor Protection and Law Enforcement

|

We consider the visitors as our guests, and try

to solve most violations in a one on one situation. In unusual

incidents we issue citations which carry a monetary fine, and sometimes

we are forced to make arrests.

-- Gordon D. Boyd, LARO Acting Superintendent, 1985 [100] |