|

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Montana |

|

NPS photo | |

A Clash of Cultures

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument memorializes one of the last armed efforts of the Northern Plains Indians to preserve their ancestral way of life. Here in the valley of the Little Bighorn River on two hot June days in 1876, more than 260 soldiers and attached personnel of the U.S. Army met defeat and death at the hands of several thousand Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. Among the dead were Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and every member of his immediate command. Although the Indians won the battle, they subsequently lost the war against the military's efforts to end their independent, nomadic way of life.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn was but the latest encounter in a centuries-long conflict that began with the arrival of the first Europeans in North America. That contact between Indian and Euro-American cultures had continued relentlessly, sometimes around the campfire, sometimes at treaty grounds, but more often on the battlefield. It reached its peak in the decade following the Civil War, when settlers resumed their vigorous westward movement. These western emigrants, possessing little or no understanding of the Indian way of life, showed slight regard for the sanctity of hunting grounds or the terms of former treaties. The Indians' resistance to those encroachments on their domain only served to intensify hostilities.

In 1868, believing it "cheaper to feed than to fight the Indians," representatives of the U.S. government signed a treaty at Fort Laramie, Wyo., with the Lakota, Cheyenne, and other tribes of the Great Plains, by which a large area in eastern Wyoming was designated a permanent Indian reservation. The government promised to protect the Indians "against the commission of all depredations by people of the United States."

Peace, however, was not to last. In 1874 gold was discovered in the Black Hills, the heart of the new Indian reservation. News of the strike spread quickly, and soon thousands of eager gold seekers swarmed into the region in violation of the Fort Laramie treaty. The army tried to keep them out, but to no avail. Efforts to buy the Black Hills from the Indians, and thus avoid another confrontation, also proved unsuccessful. In growing defiance, the Lakota and Cheyenne left the reservation and resumed raids on settlements and travelers along the fringes of Indian domain. In December 1875, the commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered the tribes to return before January 31, 1876, or be treated as hostiles "by the military force." When the Indians did not comply, the army was called in to enforce the order.

The Campaign of 1876

The army's campaign against the Lakota and Cheyenne called for three separate expeditions—one under Gen. George Crook from Fort Fetterman in Wyoming Territory, another under Col. John Gibbon from Fort Ellis in Montana Territory, and the third under Gen. Alfred H. Terry from Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory. These columns were to converge on the Indians concentrated in southeastern Montana under the leadership of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other war chiefs.

Crook's troopers were knocked out of the campaign in mid-June when they clashed with a large Lakota-Cheyenne force along the Rosebud River and were forced to withdraw. The Indians, full of confidence at having thrown back one of the army's columns, moved west toward the Little Bighorn River. Meanwhile, Terry and Gibbon met on the Yellowstone River near the mouth of the Rosebud. Hoping to find the Indians in the Little Bighorn Valley, Terry ordered Custer and the 7th Cavalry up the Rosebud to approach the Little Bighorn from the south. Terry himself would accompany Gibbon's force back up the Yellowstone and Bighorn rivers to approach from the north.

The 7th Cavalry, numbering about 600 men, located the Indian camp at dawn on June 25. Custer, probably underestimating the size and fighting power of the Lakota and Cheyenne forces, divided his regiment into three battalions. He retained five companies under his immediate command and assigned three companies each to Maj. Marcus A. Reno and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen. A twelfth was assigned to guard the slow-moving pack train.

Benteen was ordered to scout the bluffs to the south, while Custer and Reno headed toward the Indian camp in the valley of the Little Bighorn. When near the river, Custer turned north toward the lower end of the encampment. Reno, ordered to cross the river and attack, advanced down the valley to strike the upper end of the camp. As he neared the present site of Garryowen Post Office, a large force of Lakota warriors rode out from the southern edge of the encampment to intercept him. Forming his men into a line of battle, Reno attempted to make a stand, but there were just too many Indians. Outflanked, he was soon forced to retreat in disorder to the river and take up defensive positions on the bluffs beyond. Here he was joined by Benteen, who had hurried forward under orders from Custer to "Come on; Big village, be quick, bring packs."

No one knew precisely where Custer and his command had gone, but heavy gunfire to the north indicated that he too had come under attack. As soon as ammunition could be distributed, Reno and Benteen put their troops in motion northward. An advance company under Capt. Thomas B. Weir marched about a mile downstream to a high hill (afterwards named Weir Point), from which the area now known as the Custer battlefield was visible. By now the firing had stopped and nothing could be seen of Custer and his men. When the rest of the soldiers arrived on the hill, they were attacked by a large force of Indians, and Reno ordered a withdrawal to the original position on the bluffs overlooking the Little Bighorn. Here these seven companies entrenched and held their defenses throughout that day and most of the next, returning the Indians' fire and successfully discouraging attempts to storm their position. The siege ended finally when the Indians withdrew upon learning of the approach of the columns under Terry and Gibbon.

Meantime, Custer had ridden into history and legend. His precise movements after separating from Reno have never been determined, but vivid accounts of the battle by Indians who participated in it tell how his command was surrounded and destroyed in fierce fighting. Northern Cheyenne Chief Two Moon recalled that "the shooting was quick, quick. Pop-pop-pop very fast. Some of the soldiers were down on their knees, some standing. . . . The smoke was like a great cloud, and everywhere the Sioux went the dust rose like smoke. We circled all around him—swirling like water around a stone. We shoot, we ride fast, we shoot again. Soldiers drop, and horses fall on them."

In the battle, the 7th Cavalry lost the five companies (C, E, F, I, and L) under Custer, about 210 men. Of the other companies of the regiment, under Reno and Benteen, 53 men were killed and 52 wounded. The Indians lost no more than 100 killed. They removed most of their dead from the battlefield when the large encampment broke up. The tribes and families scattered, some going north, some going south. Most of them returned to the reservations and surrendered in the next few years.

Touring the Battlefield

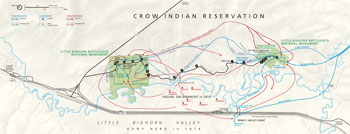

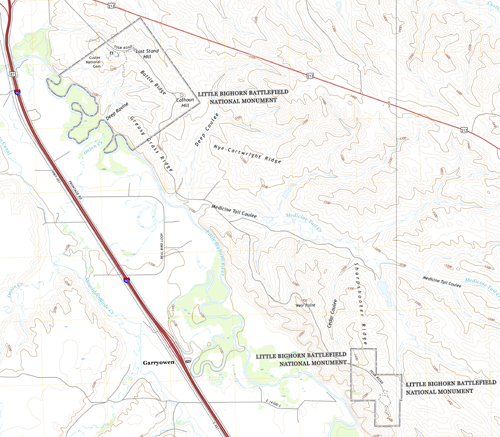

(click for larger maps) |

The Battle of the Little Bighorn continues to fascinate people around the world. For most, it has come to illustrate a part of what Americans know as their western heritage. Heroism and suffering, brashness and humiliation, victory and defeat, triumph and tragedy—these are the things people come here to ponder. Before starting your tour, stop at the visitor center, where park rangers can answer your questions and help plan your day. Museum exhibits and literature also help to explain these historical events.

Indian Encampment On June 25, 1876, approximately 7,000 Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, including 1,500-2,000 warriors, are encamped below along the Little Bighorn River. Led by Sitting Bull, they refused to be restricted to their reservation, preferring their traditional nomadic way of life.

Custer's Advance From the Crow's Nest, Custer's Crow and Arikara scouts see evidence of an Indian encampment. Convinced that he has been discovered, Custer divides his command to strike the camp before it can scatter. He orders Maj. Marcus Reno's battalion to attack the encampment. Custer, with approximately 225 men, veers to the northwest in pursuit of mounted warriors and appears on the ridge to your left for the first view of the camp.

Valley Fight After fording the Little Bighorn, Reno's battalion charges the encampment. Convinced that he is vastly outnumbered, Reno dismounts and forms a skirmish line across the valley, firing into the lodges. Warriors rush forward to defend the camp and outflank Reno's command, forcing it into the timber.

Retreat Forced to withdraw, Reno's retreat becomes a rout as pursuing warriors ride in among the troopers, killing about 40 soldiers as they attempt to reach the safety of the bluffs beyond the Little Bighorn River. Warrior casualties are few.

Hilltop Defense Major Reno's shattered battalion takes up positions here and is soon joined by Capt. Frederick Benteen's battalion. The surrounded troops make a determined stand until the next afternoon, when the Indians withdraw.

Sharpshooter Ridge From the ridge on your right, Custer watches Reno's attack in the valley. In this vicinity Custer sends back a messenger with orders for the pack train to reinforce him. Custer's five companies descend Cedar Coulee and march northward, trying to locate the lower end of the encampment. After Custer's defeat, this promontory is occupied by Lakota and Cheyenne warriors who pour a deadly fire into Reno and Benteen's companies, thus the name Sharpshooter Ridge.

Weir Point Late on the afternoon of June 25, Capt. Thomas Weir leads his company to this hill in an attempt to locate Custer. The Lakota and Cheyenne, returning from destroying Custer's immediate command, force these troops to abandon this position in favor of their hilltop defense one mile south.

Medicine Tail Coulee After leaving Cedar Coulee, Custer descends Medicine Tail Coulee. Near here, Custer sends back a message for Captain Benteen to join him and "be quick." Most warriors are still engaged with Reno in the valley, yet some are aware of Custer's advance.

Medicine Tail Ford The Miniconjou, Sans Arc, and Cheyenne camps are on the western bank. Indian accounts indicate that at least part of Custer's battalion came to the ford. Perhaps as many as three of the companies (C, I, and L) remain on Nye-Cartwright Ridge, probably to attract Benteen. At first only a small number of warriors defend the ford from the west side. They are soon reinforced, and pursue Custer's command to Battle Ridge.

Deep Coulee After the brief encounter at the ford, two companies (E and F) withdraw up the ravine to your right. The other three companies skirmish with warriors on the high ridge ½ mile to your right and soon reunite with the other two companies on Battle Ridge.

Greasy Grass Ridge After pursuing Custer's command, warriors position themselves along the ridge to your left. Indian cartridges found here indicate overwhelming fire directed at soldiers on the high ridge to your right front.

Lame White Man Charge Indian warrior accounts indicate that soldiers from Company C charged into the coulee on your left to break up the massed warriors. Coming under heavy fire, they were forced back to the ridge, where most were killed. Lame White Man, a Southern Cheyenne, led the attack but fell a short time later.

Calhoun Hill Custer's command briefly reunites here. Company L, under Lt. James Calhoun, skirmishes with Gall, Crow King, Lame White Man, Two Moons, and other warriors. Lakota and Cheyenne soon overrun this hilltop and stampede cavalry horses held in the ravine to your left.

Keogh-Crazy Horse Fight The markers to your right represent soldiers killed during the retreat toward Capt. Myles Keogh's Company I. A devastating charge led by Oglala Lakota Crazy Horse and White Bull cut down retreating soldiers of Companies C and I, who are attempting to join Custer's command on Last Stand Hill.

Deep Ravine Custer's command deploys in the current national cemetery area and advances into the basin across the road to your left before it is forced to withdraw to Last Stand Hill. Toward the end of the battle, some soldiers charge or flee toward Deep Ravine but are quickly overwhelmed and killed.

Last Stand Hill On this knoll Custer and approximately 41 men shoot their horses for breastworks and make a stand. Approximately 10 men, including Custer, his brother Tom, and Lt. William Cooke, are found in the vicinity of the present 7th Cavalry memorial. Other soldiers are found within the enclosure area below the knoll.

Memorial Markers After the battle, Lakota and Cheyenne families remove their dead, estimated between 60-100, and place them in tipis and on scaffolds and hillsides. On June 28, 1876, the bodies of Custer and his command are hastily buried in shallow graves at or near where they fell. In 1877 the remains of 11 officers and two civilians are transferred to eastern cemeteries. Custer's remains are reinterred at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. In 1881 the remains of the rest of the command are buried in a mass grave around the base of the memorial shaft bearing the names of the soldiers, scouts, and civilians killed in the battle. In 1890 the Army erects 249 headstone markers across the battlefield to show where Custer's men had fallen. In 1999 the National Park Service began erecting red granite markers at known Cheyenne and Lakota warrior casualty sites throughout the battlefield. These unique markers are an important addition to the historic cultural landscape, providing visitors with a balanced interpretive perspective of the fierce fighting that occurred here in 1876.

About Your Visit Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument lies within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana, one mile west of I-90/U.S. 87. Crow Agency is two miles north. Billings, Mont., is 65 miles northwest, and Sheridan, Wyo., is 70 miles to the south.

No camping or picnicking facilities are in the park. Federal law prohibits the removal or disturbance of any artifact, marker, relic, or historic feature. Metal detecting on park land or adjacent Indian lands is prohibited. Remember, you are in rattlesnake country; stay on the pathways while walking the battlefield. Rangers will offer prompt assistance in case of accidents, but you can prevent them by being cautious.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

Documents

1876-1976 Centennial Commemoration: Battle of the Little Bighorn (June 24-25, 1976)

A Survey of the Vascular Plants and Birds of Little Bighorn National Battlefield Final Report (Jane H. Bock and Carl E. Bock, July 2006)

Acoustic Monitoring Report: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR—2014/877 (Misty D. Nelson, May 2014)

Alternative Transportation Feasibility Study — Volume II: Options and Criteria for Evaluation, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (November 2012)

An Environmental History of Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Gregory E. Smoak, December 30, 2015)

Archeological Mitigation of the Federal Lands Highway Program Plan to Rehabilitate Tour Road, Route 10, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 94b (Douglas D. Scott, 2006)

Cheyennes at the Little Big Horn — A Study of Statistics (Harry H. Anderson, extract from North Dakota History, Vol. 27 No. 2, Spring 1960, ©State Historical Society of North Dakota)

Final General Mangement Plan and Development Concept Plans, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (August 1986, updated May 1995)

Foundation Document, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana (March 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana (January 2015)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2011/407 (K. KellerLynn, June 2011)

Historical Handbook Series No. 1: Custer Battlefield National Monument, Montana (HTML edition) (Edward S. and Evelyn S. Luce, 1949)

Historical Handbook Series No. 1: Custer Battlefield National Monument, Montana (HTML edition) (Robert M. Utley, 1969)

Junior Ranger Program: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Ron Thomson, March 2011)

Mark Kellogg Telegraphed For Custer's Rescue (Oliver Knight, extract from North Dakota History, Vol. 27 No. 2, Spring 1960, ©State Historical Society of North Dakota)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Custer Battlefield National Monument (Scott W. Loehr and Bruce Westerhoff, May 1985)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR-2014/891 (Kimberly Struthers, Mike Britten, Donna Shorrock, Robert E. Bennetts, Nina Chambers, Heidi Sosinski and Patricia Valentine-Darby, December 2014)

Newspaper: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Date Unknown)

"Peace Through Unity": Indian Memorial Dedication (June 25, 2003)

Proper Functioning Condition Assessment of the Little Bighorn River, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/WRD/NRR-2013/707 (Mike Martin, Joel Wagner, Jalyn Cummings and Mike Britten, August 2013)

Rocky Mountain Network News and Highlights, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Spring 2008)

Spinning Custer: A Pennsylvania Editor's Assessment of Little Bighorn (John M. Lawlor, Jr., extract from Federal History, Issue 10, ©Society for the History in the Federal Government, 2018)

Small Mammal Surveys on Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Final Report (Dean E. Person, Kathryn A. Socie and Leonard F. Ruggiero, January 20, 2006)

Soil Survey of Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana (2013)

Uncovering History: The Legacy of Archeological Investigations at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 124 (Douglas D. Scott, 2010)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR—2012/590 (Peter Rice, Will Gustafson, Daniel Manier, Brent Frakes, E. William Schweiger, Chris Lea, Donna Shorrock and Laura O'Gan, October 2012)

Vegetation Composition, Structure, and Soils Monitoring at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument: Data Report 2010-2014 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR—2016/1210 (Erin M. Borgman and E. W. Schweiger, May 2016)

Vegetation Composition, Structure, and Soils Monitoring in Grasslands, Shrublands, and Woodlands at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument: 2009 Annual Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/ROMN/NRDS—2010/088 (Donna Shorrock, Isabel Ashton, Michael Britten, Jennifer Burke, David Pillmore and E. William Schweiger, September 2010)

libi/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025