|

Lincoln Boyhood

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER II:

Environmental Overview

The historical record is as much a product of natural forces as of human endeavors. In much the same way, the extant landscape displays the interwoven influences of cultural and natural components in an ever-evolving relationship. In order to understand patterns of prehistoric human occupation in Spencer County, the natural environment of southern Indiana must be considered. Human societies at all levels of complexity are linked to the natural environment in a systemic or ecological relationship. This relationship can best be understood as the differential use of available resources, coupled with the strategies employed for exploitation of those resources. Environmental constraints work to define the set of settlement and subsistence options available to a particular social group. These include proximity to water, climactic patterns, access to lithic resources, and the presence of game and edible plants. Parameters such as these further affect site selection for settlements and influence the likelihood of the site's subsequent preservation. Only sites preserved through a combination of environmental, locational, and geographic factors remain sufficiently intact to yield information concerning prehistoric peoples. Consequently, the information available about patterns of human occupation in a given area is shaped both by the types of societies occupied the area and the contemporary and subsequent environmental conditions present at the site.

PHYSIOGRAPHY-GEOMORPHOLOGY

Spencer County is located in southwestern Indiana, approximately 150 miles south of Indianapolis and 40 miles east of Evansville. It is bounded on the west by Warrick County, on the north by Dubois County, and on the east by Perry County. The 37-mile southern boundary is formed by the Ohio River. Spencer County is approximately 400 square miles in area. [1]

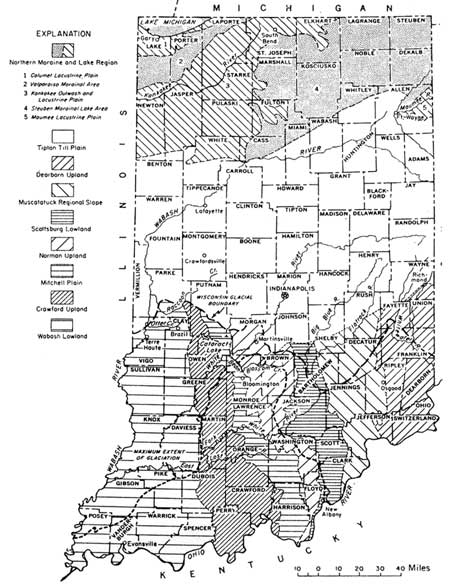

This county lies within the Wabash Lowlands physiographic unit, the largest and westernmost unit in southern Indiana (Figure 2). It is situated south of the Illinoian and Wisconsin glacial boundaries. During the Wisconsin Age (Late Pleistocene), the tremendous volume of water carried by the Wabash River created a lake that covered much of southwestern Indiana. Depositions dating from this era are responsible for the present topography of broad aggraded valleys separated by low, rolling hills. As a result, with the exception of the northeastern section, topographic relief in Spencer County is not great, with elevations generally ranging between 338 and 660 feet above sea level. In these unglaciated areas, the soil is thin and easily worn away, particularly in comparison to the soil stratigraphy in the northern half of Indiana. [2]

|

| Figure 2: Map of Indiana Showing Physiographic Units and Glacial Boundaries (Schneider, 1966: 41) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In southern Indiana, the Ohio River is bordered by bottom lands and floodplains as much as three-and-a-half miles in width. During prehistoric times, extensive swamps and marshes paralleled the river. Fully one-quarter of Spencer County's area historically was dominated by marshy bottomlands and floodplains. A few shallow lakes were present as well, with the largest being Willow Pond, located in east-central Luce Township. Sand and silt ridges were interspersed among the swamps, and likely were dry except during periods of flooding. Kellar's archaeological survey of Spencer County suggests that many of these ridges were locales for aboriginal occupation. [3]

Presently, with the exception of the Ohio River, Spencer County does not have any major waterways. Little Pigeon Creek and Anderson River form the western and eastern boundaries, respectively, of the county and both are comparatively modest streams. A number of small brooks exist, such as Big Sandy, Little Sandy, and Crooked creeks, but these often are dry during summer months. Dredging and draining are believed to have altered a number of stream courses. Deforestation of the area during the nineteenth century and subsequent agricultural practices also are likely to have contributed to changes in drainage patterns. [4]

BEDROCK GEOLOGY

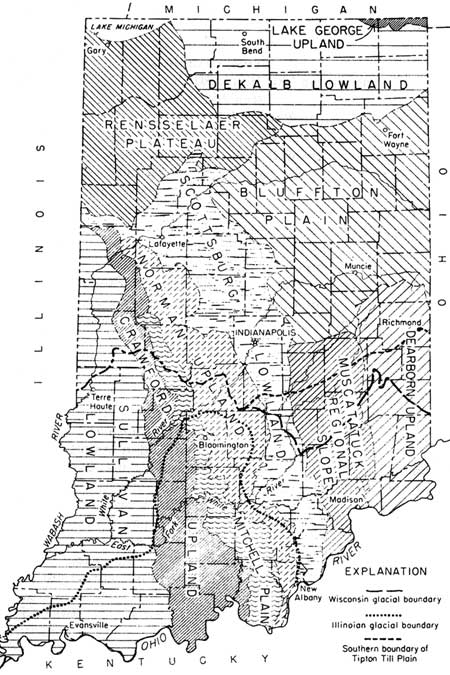

Spencer County is underlain by rocks of Pennsylvanian age (late Paleozoic Era), the youngest bedrock formations found in Indiana (Figure 3). The dip in the rock beds is generally to the west from the Cincinnati Arch. The stratigraphy is dominated by siltstones and shales, interbedded with limestone formations and coal beds. [5] Bedrock geology determined the various lithic resources available for utilization by Paleoindian cultures, the types of soils in the area (which were significant to agricultural activity), and topography. In more recent times, the proximity of the coal beds to the surface has resulted in the strip mining of much of the county.

|

| Figure 3: Map of Indiana Showing Bedrock Physiographic Units (Gutschick, 1966:54) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

LITHIC RESOURCES

Several limestones crop out within and near Spencer County that contain chert. These cherts include Holland and Lead Creek. Holland chert is a high quality blue-gray chert that crops out in southcentral Dubois and northern Spencer Counties. It was utilized by prehistoric peoples during all cultural periods for use as tools, blades, and spear points. Lead Creek has also been known as Lieber and "the black chert beneath the Mariah Hill coal seam." It is a poor to medium quality fossiliferous chert found in residual contexts in much of Spencer County. Other chert resources in the vicinity include Ditney chert in Warrick County, Haney chert in Perry, Crawford, and Orange Counties, and Derby chert in Perry County. All of these are of medium quality. The high quality Wyandotte chert crops out some 35 miles to the east, along the Crawford and Harrison County border. [6]

SOILS

|

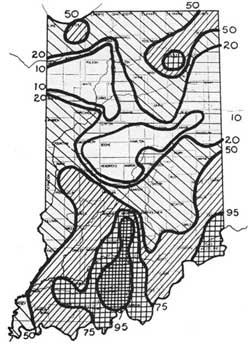

| Figure 4: 1935 Map Showing Percent of Sheet Erosion and Gullying by County (Sieber and Munson, 1994: 86) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In the northern two-thirds of Indiana, soils are generally deep, silty, light-brown loams that are the result of glaciation. The unglaciated southern portion of Indiana has thinner, less fertile soil that consists of heavy clays, brown silt loams, or yellowish silty to sandy deposits. Their fertility was greatly depleted by pioneer farming practices that relied on a succession of corn crops without any crop rotation. Over the course of the nineteenth century, deforestation further contributed to problems with erosion and also led to increased instances of flooding and drought. During the 1930s, 100,000 acres in southern Indiana were assessed to be in serious stages of erosion (Figure 4). [7]

Soils in Spencer County are formed in the Ohio River floodplain and terraces, from sands derived from Pleistocene glacial outwash and related lacustrine deposits, from fine-grained windblown (loess) deposits, and from weathered sandstone and shale bedrock. The Silvan-Alford-Hosmer Association consists of silts and loess derived from windblown deposits on the eastern edge of the Wabash River Valley. These soils are found on gently rolling hills and ridges, and are generally well-drained. The Zanesville-Gilpin-Montevallo Association soils form in dissected sandstone and shale uplands in the northern half of Spencer County. These soils are moderately to poorly drained. The rugged character of this area of the county historically has not lent itself to profitable agricultural pursuits. [8]

The alluvial terrace soils along the Ohio River, primarily of the Wheeling series, are developed in silty and sandy alluvium. The well-drained Wheeling soils provide a rich basis for agricultural endeavors, an asset important to Paleoindian cultures, successive Indian tribes, and Euroamerican settlers. In comparison, related alluvial terrace soils such as Sciotoville soils are moderately well drained, Weinbach soils are somewhat poorly drained, and the Giant soils are poorly drained. The Bloomfield-Princeton Association formed in the sand dune belt along the eastern edge of the Wabash Valley. The Bloomfield and Chelsea soils are well drained fine sandy loams that also were conducive to crop cultivation, while the Ayrshire and Lyles soils are somewhat poorly drained loamy fine sands. [9]

CLIMATE

Pollen studies conducted in areas adjacent to southern Indiana indicate several climatic shifts occurred in Indiana during the Holocene Period. As the glacial ice sheets retreated across North America, spruce-dominated boreal forests occupied areas adjacent to the ice margins, including northern Indiana. Open subarctic grasslands were also present, probably in a complex mosaic on the landscape defined by local conditions. [10] Gradual warming occurred after 10,000 B.C. and spruce forests were replaced by northern oak and pines. [11]

A dryer, warmer climatic interval occurred from 5000 to 2000 BC. This resulted in a significant retreat of grasslands from northern Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota. [12] The effects of this warming are unknown for the oak and pine forests of southcentral Indiana but, presumably, there was some shift of localized prairie areas. Subsequent to 2000 BC, a climate much like the present prevailed, with occasional cooler and wetter episodes, and a modern deciduous forest.

As the southernmost portion of Indiana, Spencer County presently has a continental climate with cold winters and warm, humid summers. The average temperature is 37 degrees F. in winter, and 78 degrees F. in summer. During the summer, however, temperatures above 90 degrees F. are not unusual. The total annual precipitation is around 45 inches, of which 23 inches fall from April through September. Average seasonal snowfall is 10 inches. Brief droughts are not uncommon during summer, and can negatively affect agricultural yields. The prevailing wind is from the south/southwest. Tornadoes and severe thunderstorms occur occasionally in spring and summer. As such, severe climactic conditions presently are an exception, rather than the norm for Spencer County. The relatively warm temperatures, combined with the extensive bottomlands and adequate rainfall, contributed to the establishment of varied and extensive flora and fauna in the county. [13]

FLORA AND FAUNA

The Federal government's General Land Office initially surveyed Indiana between about 1799 and 1834, providing some documentation of the climax forests. [14] Bearing trees were recorded during the survey, providing information on the vegetation as it existed prior to Euroamerican settlement. Upwards of seven-eighths of the state's land area was forested during this period, with walnut, ash, poplar, elm, hickory, maple, and oak constituting the predominant species.

A wide variety of animal resources were available to the aboriginal and early Euroamerican inhabitants of Spencer County. In the Indiana of 1816, it is estimated that as many as 66 species of mammals existed, including bison, elk, black bear, mountain lion, gray and red wolf, porcupine, eastern spotted skunk, wolverine, river otter, and lynx, as well as current inhabitants, such as white-tail deer, red and gray fox, eastern cottontail rabbit, striped skunk, opossum, beaver, raccoon, and groundhog. [15] Federal surveys also recorded over 300 edible plants in Indiana, including nuts, fruits, berries, roots, and tubers, that would have provided a significant source of food for prehistoric inhabitants. In southern Indiana, the marshes and swamps created by the Ohio River and its tributaries provided a habitat for aquatic birds, while the waterways themselves were sources of turtles, freshwater fish, and mussels. [16] Archaeological investigations undertaken in Spencer County in the early to mid-twentieth century discovered several Archaic-period shell middens that attested to the reliance of some prehistoric peoples on rivers as a source of food. [17]

The ready availability of a variety of food sources and the relatively temperate climate combined to make southwestern Indiana an area of intensive occupation during the prehistoric period. As previously noted, deforestation throughout Indiana, and particularly in southern Indiana, had a profound effect on the natural environment by promoting soil erosion and altering drainage patterns. With approximately 100,000 acres of land in southern Indiana experiencing severe erosion by the 1930s, remedial reforestation programs were initiated to counter this environmental degradation. [18]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003