|

Lincoln Boyhood

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER VIII:

Post-Lincoln History of Property

As previously noted, the Lincolns sold their original quarter-section farmstead to Charles Grigsby in February, 1830, for the sum of $125. Grigsby owned the property for five years, then sold it to Edley Brown in December, 1835. Ownership changed hands twice more in the next three years, from Brown to James Sally in 1837, and from Sally to Joseph Gentry in 1838. Gentry retained the property until 1850, then sold the north forty acres to Elijah Winkler. Three years later, Gentry sold the south forty acres to William Oskins. Within six years, the latter parcel again was acquired by the Gentry family when James Gentry, Jr., purchased it from Oskins. [200] Throughout these exchanges of ownership, it is presumed that the land continued to be cultivated or at least used for pasturage. No one is believed to have lived at the Lincoln farm, however, as the 1817 cabin had been removed by 1865 and later descriptions of the 1829 house indicate it had been left to deteriorate for a number of years.

LINCOLN CITY

Like much of the rest of the country, Indiana experienced an astonishing burst of railroad construction during the middle decades of the nineteenth century. The majority of the state's rail lines traversed central and northern Indiana, particularly around the growing industrial centers of Indianapolis and Gary. In southcentral Indiana, only a few rail lines existed by 1880, including the Lake Erie, Evansville & Southwestern, the Evansville & Terre Haute, and the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago. In Spencer County, the Board of Commissioners accepted a petition signed by more than 100 local residents who requested an election on the issue of local aid to the Rockport & Northern Central Railway Company for construction of a route through the county. Spencer County voters approved provision of 2 percent of the county's 1868 tax levy (a total of $97,891) for the project. Residents of neighboring DuBois County approved a similar levy and construction on the road bed between Rockport and Jasper began in 1869. Around 1872, the Rockport & Northern Central Railway and the Cincinnati & Southwestern Railway companies consolidated to form the Cincinnati, Rockport & Southwestern Railway Company. [201] Financial shortfalls plagued the company and halted construction for a time. Eventually, the Rockport Banking Company came to the struggling company's aid, agreeing to advance $10,000 for each five miles of track. Construction resumed at a more rapid pace and in May, 1874, the first excursion train left Rockport bound for Coal Hill Station at the Spencer/DuBois county line. Construction of the rail line continued at a fitful pace through the late 1870s, finally reaching Jasper in February, 1879. A few months later, the Cincinnati, Rockport & Southwestern Railway sold its assets to the Evansville Local Trade Railway Company. In 1881, this consolidated company became the Evansville, Rockport & Eastern Railway Company, but within the year it had been absorbed by the Louisville, New Albany & St. Louis Railway Company, which in turn was soon renamed the Louisville, Evansville & St. Louis Company. Such convoluted reorganizations and consolidations were typical of railroad companies during this period. The various mergers meant that the short line from Rockport to Jasper ultimately became connected to a much larger rail system that extended from Louisville to St. Louis. [202]

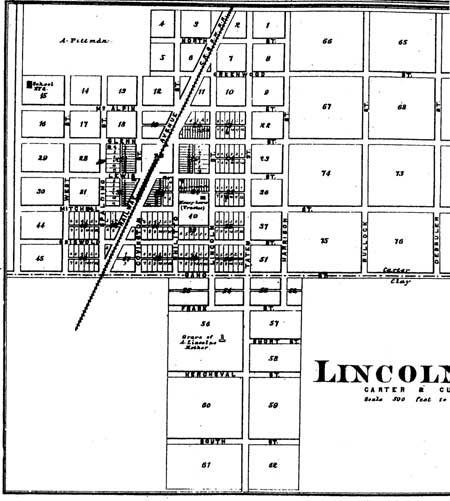

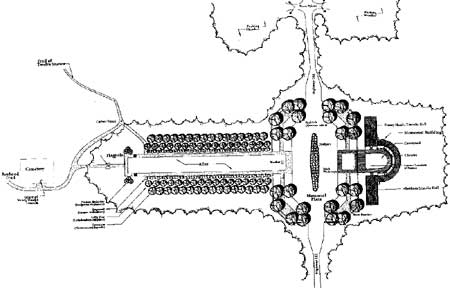

Construction of railroad routes almost invariably prompted land speculation and development along the proposed routes. The rail line through Spencer County was no exception. In 1871, James Gentry sold the former Lincoln farmstead to John Shillito, Henry Lewis, Robert Mitchell, and Charles West. These four speculators from Cincinnati intended to plat a community along the Cincinnati, Rockport & Southwestern's new line (Figure 19). The post office originally was called Kercheval, undoubtedly after R. T. Kercheval, who had rescued the company in 1874. By 1881, the town's name had been changed to Lincoln City, in recognition of its proximity to the old Lincoln farm. The community had several stores, including those maintained by James Gentry, Jr., William Gaines, W. J. Chinn, and Walter Howard. S. N. Hilt operated a blacksmith shop, while T. N. Robinson kept a hotel. The village also had a saloon and train station. [203]

|

| Figure 19: 1879 Map of Lincoln City (Griffing, 1879) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The community prospered for a time, with as many as twelve passenger trains passing through on a daily basis. Three rounds trips were made to Cannelton and Rockport, and six to Evansville. The railroad company constructed a fourteen-acre lake to furnish a water supply and the site also was used for recreational activities, but few traces remained of the forest that had covered much of the area when the Lincolns arrived in 1816. At its height, Lincoln City supported two hotels, four stores, two restaurants, a livery barn, and a tavern. In 1904, a brick schoolhouse was erected just southwest of the Lincoln cabin site. [204]

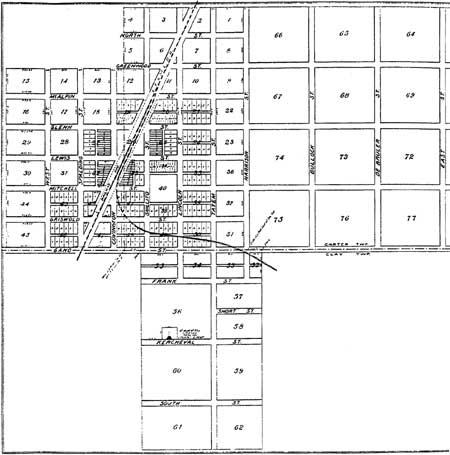

Published plat maps from the late-nineteenth century identified the site of Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave, on the south side of Lot 56, a short distance south of the town center (Figure 20). In 1879, the town founders donated a half-acre around the Lincoln grave to the Spencer County Commissioners to preserve the site. Around the turn of the century, the cemetery was enlarged with the addition of several new graves. Several efforts also were undertaken to mark Nancy Lincoln's grave and to commemorate her role as the mother of the nation's sixteenth president. [205] The reasons that this previously abandoned grave began to be transformed into a shrine are rooted in the popular culture of the late nineteenth century.

|

| Figure 20: 1896 Map of Lincoln City (Wright, 1896) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

MEMORIALIZING THE LINCOLNS

By the 1870s, the popular perception of Abraham Lincoln began a gradual process in which the slain president was elevated to an almost mythic status. Sites associated with his life grew to be popular destination points for tourists and souvenir seekers. The farmstead where he spent his formative years became one of many memorials, along with that of his birthplace in Hodgenville, Kentucky, and his law office in Springfield, Illinois, that were established in the half-century following his death. The Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial commemorates the period Abraham Lincoln spent in southern Indiana and also includes the final resting place of his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. The memorial has passed through three interpretation phases. It began as a shrine to Nancy Hanks Lincoln and, by extension, the cult of motherhood that characterized the Victorian era. During the 1930s, the memorial was transformed to commemorate Lincoln and his lifetime of accomplishments. Thirty years later, the site's programs were expanded to include a parallel interpretive theme with the construction of the Living History Farm.

THE FIRST MEMORIAL TO NANCY HANKS LINCOLN

From the 1830s to the 1870s, the Lincoln homestead was transferred from landowner to landowner. The dwellings the Lincolns constructed during their tenure fell into disrepair. Many of the area's original settlers moved away or died, leaving fewer and fewer people to visit and care for the cemetery where Lincoln's mother lay buried. By the time Lincoln was assassinated on 15 April 1865, the cemetery had been all but forgotten. His death rekindled a local interest in the Lincolns' Indiana connections, however, and efforts began to locate the family homestead and cemetery. By this date, the 1817 cabin had disintegrated, while the remnants of the 1829 cabin, which the Lincolns never occupied, became a popular spot for tourists to be photographed, at least until it was literally pulled to pieces by souvenir hunters. [206]

A group of twenty-four local residents reportedly convened to determine the correct location of the pioneer cemetery. They included John Richardson and descendants of Nancy Brooner, who died shortly before Nancy Hanks Lincoln. After gathering at the former Lincoln farmstead, this group agreed that the cemetery was situated in a corner of a field then owned by John Carter. In July 1874, a story appeared in the local newspaper stating that the grave of Nancy Lincoln was unmarked. Moved to redress the shortcoming, Professor Joseph D. Armstrong, editor and superintendent of schools, placed a sandstone marker at the grave in the fall of 1874. [207] This marker, however, was destroyed within only a few years by souvenir hunters who chipped away pieces to take with them. The vandalism made it apparent to local leaders that the site was becoming a popular memorial site and thus prompted the first efforts at preservation.

In 1879, P.E. Studebaker, vice president of the Studebaker Corporation, presented a contemporary marker to the site (Plate 1). This marble marker remains the official marker of Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave. It stands approximately two feet in height on a marble base. The lancet-shaped monument is made of Italian marble and inscribed with "Nancy Hanks |Lincoln | Mother of President | Lincoln | Died Oct 5, A.D. 1818 | Aged 35 years | Erected by a friend of her martyred son 1879." Around this same time, Civil War General John Veatch of Rockport coordinated a local fundraising effort to pay for an ornamental iron fence around the graves of both Nancy Hanks Lincoln and Nancy Brooner. [208]

Preservation efforts such as these were akin to similar undertakings associated with other former American presidents, including Ann Pamela Cunningham's work to save George Washington's Mount Vernon and the Ladies' Hermitage Association's acquisition of Andrew Jackson's home, The Hermitage. These movements were part of a larger search for national identity taking place in the United States, with Americans focusing on the deeds of great leaders for inspiration. [209] The establishment of historical associations ranked among the first manifestations of this process. On an ad hoc basis, the organizations also established the first guidelines concerning the types of sites considered worthy of preservation, who should be responsible for their maintenance, and how they should be interpreted. A critical underpinning to these directives was the assumption that private citizens, rather than government, should undertake the care of historic sites. Equally important was the notion that sites associated with military and political figures properly must be treated as shrines or icons. The initial efforts to preserve the Nancy Hanks Lincoln site clearly falls within this period of preservation theory.

|

| Plate 1: 1959 Photo of Nancy Hanks Lincoln Grave Marker and Ornamental Iron Fence |

The gravesite became symbolic of motherly devotion to one of America's greatest political leaders. The emphasis on a "sainted mother" also played into the cult of motherhood that was popularized in the literature of the early and mid-nineteenth century. A central tenet of the cult of motherhood was that women were responsible for perfecting an alternative to the commercial world and providing children (especially sons) with a moral education. [210] Domestic writings and sermons across the country popularized these ideas. Collected decades after the fact, oral histories concerning Nancy Hanks Lincoln's death clearly show the influences of this movement. With her supposed dying words, she asked her children "to be good and kind to their father, to one another, and to the world." She also reportedly expressed a hope that the children would live as they had been taught by her, to love, revere, and worship God. Many of the oral histories taken in the late nineteenth century describe Nancy Hanks Lincoln as "a woman of great good sense and morality." Her nephew, Dennis Hanks, offered this description in 1865: "Mrs. Lincoln always taught Abe, goodness, kindness, read the good Bible to him, taught him to read and to spell, taught him sweetness and benevolence as well." [211]

ESTABLISHING NON-PROFIT ASSOCIATIONS

By the late nineteenth century, the emotional power of the cult of motherhood had begun to fade and popular interest in the grave of Abraham Lincoln's mother waned. By 1897, the gravesite again was neglected, although the adjacent cemetery remained in use by local residents. In response, Governor James Mount helped form the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association (NHLMA), which was charged with raising money for the site's maintenance. Initial fundraising efforts were less than successful, with only $56.52 raised by 1900. That year, however, the Spencer County Commissioners deeded 16 acres of land to the NHLMA, giving the organization full control over the site, while Robert Todd Lincoln donated $1000 toward the maintenance of the grave. Other changes included the addition of a second memorial stone in 1902. The stone was donated by J. L. Culver of Springfield, Illinois, and stood outside of the 1879 iron fence. The inscribed stone rested on a substantial stone base and measured approximately three feet tall and one foot deep. Its inscription is illegible from the available photographs. [212]

In the early 1900s, the NHLMA also began plans to turn the site into a park. NHLMA constructed a large picnic shelter near the cemetery and drilled a well to supply fresh water. Local citizens soon complained that the site was not being maintained properly, with visitors leaving picnic trash and carelessly walking on graves. In 1907, the General Assembly responded by creating a Board of Commissioners to care for the site. Some of the first steps to improve the site included construction of a new fence around the entire sixteen-acre site and establishment of a monumental driveway between the grave and the nearby road, which was then known as Lincoln Trace. Landscape architect J. C. Meyerburg of Tell City designed a gated entry featuring an eagle and lion statuary to highlight the driveway. Dead trees also were removed and ornamental plantings were added. [213]

In 1917, preservation efforts began to expand beyond Nancy Lincoln's grave, when local residents attempted to locate the site of Thomas Lincoln's cabin. Preceding these efforts had been much discussion concerning the actual location of the cabin and whether the dwelling remained standing in 1865, when tourists began making pilgrimages to the site. [214] This alleged site was located in the schoolyard of the Lincoln City graded school, which was erected in 1904. Approximately twenty people gathered here in 1917, at which time they located three or four stones and some bits of crockery, thus substantiating in the popular mind that the actual hearth from the cabin had been located. On April 28, 1917, a stone marker was erected in the schoolyard and read "Spencer County Memorial to Abraham Lincoln who lived on this spot from 1816-1830." [215]

DESIGNING THE LINCOLN STATE MEMORIAL

The enlarged commemorative project, now known as Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Park, continued to attract visitors, and local citizens remained displeased with the behavior of visitors. Finally, in 1923, Col. Richard Lieber, who served as Director of the Indiana Department of Conservation, determined that designation of the memorial site as a state park was in keeping with his department's plan for developing a statewide system of parks. The State legislature created the Lincoln Memorial Commission to replace the park's Board of Commissioners as administrators of the site. The organization received a $5000 appropriation to erect a suitable memorial. In 1925, the State acquired the cemetery and a surrounding tract of land, totaling 60 acres; this was augmented in 1929 when Frank C. Ball of Muncie, Indiana, bought an additional 29 acres and donated it to the state. [216] Indiana Governor Ed Jackson also appointed 125 people to the Indiana Lincoln Union (ILU), which was to be responsible for raising funds to create a new memorial to Abraham Lincoln. The group was led by some of the most prominent professionals in Indiana, including Anne Studebaker Carlisle and Paul V. Brown. Thus began the second phase in the site's interpretive development, as this board represented the instigation of corporate philanthropy in the maintenance and interpretation of historic sites, a trend that was occurring nationwide at numerous historic sites.

During this phase of development, the park began to be transformed into a carefully designed landscape intended to convey a specific emotional experience. In December 1926, the ILU invited nationally known landscape architect Fredrick Law Olmsted, Jr., and architect Thomas Hibben to the site. Olmsted's services were contracted to assess the existing commemorative landscape and to create a preliminary plan that would clearly define future development. [217] The two architects intended to simplify and rationalize the park's plan while remaining true to the original mission of developing a monument to Abraham Lincoln's greatness. In so doing, they created the foundation for the memorial's development throughout the remainder of the twentieth century.

Olmsted's first assessment of the site concluded that it contained too many distractions. He stated that the combination of utilitarian structures, such as the road, railroad, and picnic shelter, along with the cast iron fences, gilded lions, and exotic shrubs distracted attention from the peaceful surroundings of the cabin site and Nancy Lincoln's grave. To remedy the situation, Olmsted sought to simplify the site and create what he termed "the Sanctuary." [218]

Olmsted's plan removed most of the elements that had been added to the park over the preceding fifty years. The project was strikingly similar to preservation activities elsewhere in the United States, such as at Colonial Williamsburg, in which major elements of the existing built environment were stripped away to create a visitor's experience that would satisfy contemporary tastes. The result was a divorce of the park site from its historic context and the creation of a frozen moment in time that seemed to represent an experience visitors would accept as authentic. Such a selective vision of the past is characteristic of efforts to interpret historic events, with the popular audience and scholars alike engaging in a deliberate selection and evaluation of past events, experiences, and processes. [219] At the Lincoln park, this process of "reconstructing" the past included removal of most of the structures associated with the small town of Lincoln City that stood near the cabin site, as well as the removal of ornamental shrubs and other plants located at the cemetery. The only monument not removed was the Studebaker grave marker. Other efforts under the direction of Olmsted included the Lincoln Memorial Commission's acquisition of 428 acres, which they reforested with native trees and shrubs, and the ILU's plans to move the old Lincoln trace that bisected the cabin and gravesite. All of this work resulted in the creation of a blank slate from which to begin a new effort at memorializing Abraham Lincoln. Olmsted sought to create a landscape that was monumental and would stimulate visitors to have "their own inspiring thoughts and emotions about Lincoln." [220]

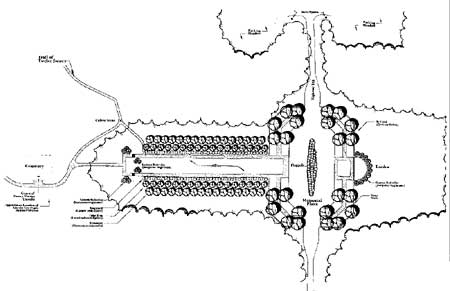

Olmsted's landscape design for the Lincoln park was derived from the City Beautiful Movement of the early twentieth century. This movement evolved out of a relationship between architects, landscape architects, and urban planners and involved creating picturesque landscapes with carefully controlled views framed by naturalistic features that were either part of the original landscape or man-made. A central element of the Olmsted plan was the creation of a primary vista known as the allee, with a cruciform arrangement that had the United States flag at its center (Figure 21). The cruciform arrangement provided for east-west and north-south traffic along with a strong spiritual image. Although religious symbolism imbued Olmsted's plan, his only overt reference to this was in the use of the religious word "Sanctuary." [221]

|

| Figure 21: Allee and Plaza Site Plan, 1927-1938 (McEnaney, 2001: 15) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The ILU added additional elements that emphasized the religious context of the site, especially through references to Nancy Lincoln as the "sainted Mother," while the site itself was "sacred soil." Another aspect of commemorating this sacred quality was the effort to preserve the cabin site in a way deemed appropriate by the ILU. The Lincoln City schoolhouse had been constructed near the site in 1904 and thirteen years later, a marker was erected that identified the location as the cabin site. Following a major fundraising drive, the ILU purchased the school property and demolished the building and other surrounding structures. After deciding a cabin reconstruction would be inappropriate, the organization hired architect Thomas Hibben to design an appropriate marker. The extant bronzed sill logs, fireplace, and hearthstones were the centerpiece of his design; these were accented with masonry retaining walls built of Bedford limestone, stone benches, and flagstone walkways. The symbolism of the hearth, as the "altar of the home," was in keeping with the ILU's predilection for treating the Lincoln Memorial as holy ground. [222]

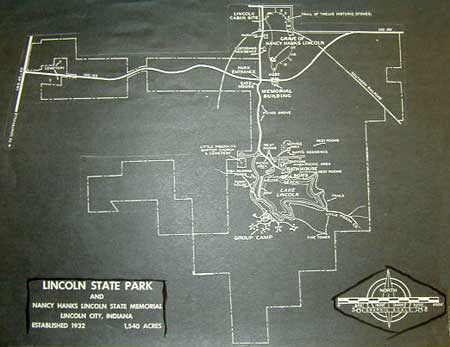

Also during the early to mid-1930s, a state park encompassing the Lincoln site was established (Figure 22). In order to undertake the state park plan and Olmsted's landscape design, Donald Johnston, the state landscape architect, was appointed to oversee implementation of these two separate but interconnected projects. Between 1929 and 1933, much of the memorial was constructed according to Olmsted's plan, although Johnston slightly revised the designs for the allee and plaza. The allee consisted of a central lawn flanked by gravel walks, which were lined on the outside by dogwood trees, tulip poplars, and sycamore trees. Furthermore, much of Lincoln City's built environment was razed. In addition to the schoolhouse, a restaurant, garage, hotel, church, 11 houses, 7 barns, and 20 outbuildings were removed from the community during the first phase of development. The 1909 ornamental fence and statuary around Nancy Lincoln's grave also were removed. Further work at the memorial included grading the site, constructing a boundary fence, relocating state highway 162, adding a drainage system and reservoir, and reforesting the grounds based on notes taken during the 1805 Federal land survey. Working with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the State planted 22,441 native trees and 15,218 shrubs at the memorial. CCC Camp 1543 also was responsible for developing the nearby Lincoln State Park, where they planted 57,000 trees and 3,200 shrubs between July 1933 and June 1934. [223] In 1931, the concept for a Trail of Twelve Stones was developed, and installation of the stones was completed in 1934. The state also integrated the cabin site into the rest of the memorial by constructing a "Boyhood Trail" that led to the family cemetery.

|

| Figure 22: Site Plan of Lincoln State Park and Nancy Hanks Lincoln State Memorial, c. 1932 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

THE TRAIL OF TWELVE STONES AND THE CABIN SITE MEMORIAL

(1931-1938)

The Trail of Twelve Stones was not part of the original Olmsted plan nor was the final plan for commemorating the cabin site. The one-mile Trail of Twelve Stones was suggested by J.I. Holcomb, president of the ILU. Holcomb proposed that a collection of stones from places associated with Abraham Lincoln should be gathered and placed along a trail linking Nancy Lincoln's grave and the cabin site. These stones were installed in 1934 and ILU members added bronze plaques in 1935. The stones include one from Lincoln's birthplace in Kentucky and another from the William Jones store in Jonesboro. Another stone came from the Western Sun and Advertiser building in Vincennes, Indiana, and a stone was taken from the Berry-Lincoln Store in New Salem, Illinois.

There are two bricks from Lexington, Kentucky, a marker commemorating his first Inaugural address, and a stone from the Old Capitol in Springfield, Illinois. Additional relics include a rock from Gettysburg and stones from the White House, the Anderson Cottage Soldiers Home, and the Petersen House where Lincoln died. The introduction of this Trail of Twelve Stones marks a change in the interpretation of the site, as the park's mission evolved from acting as a shrine to motherhood to a memorial to Lincoln himself. Nevertheless, the underlying religious tones that had characterized the park also continued to be expressed. A 1934 newspaper article entitled "Stones Taken from Scenes Vitally Linked with Life of Lincoln Made into Shrines at Nancy Hanks Park" described the stones as "shrines" where "pilgrims" could rest. [224]

The introduction of an element such as the Trail of Twelve Stones was in keeping with early twentieth century preservation practices, which often involved creating a monument for the sake of the monument, instead of focusing on actual historic events at a site. The trend continued with the development of the cabin site. In 1931, the site had no landscaping and was located in a clearing. It featured only the exposed hearthstones and the simple plaque placed at the site in 1917 by the Spencer County Commissioners. In 1931, the plaque was moved to the Trail of Twelve Stones. The Indiana Lincoln Union had previously decided that reconstruction of the cabin was not an option since there were no records of the cabin's actual appearance. Instead, architect Thomas Hibben and ILU president Colonel Richard Lieber developed a variety of models for creation of a memorial from the existing elements. The model selected was described by Hibben as follows:

The log sill is chosen as appropriate to mark the outline of the cabin; the hearth and fireplace are chosen because they have been, since time immemorial, the altar of the home, the center around which all life moved. The entire conception is cased in bronze in order that it may be durable and that it may not in any way seem a reconstruction of the original cabin. [225]

|

| Plate 2: 1959 Photo of Cabin Site Memorial |

Although the final design was accepted in 1931, the bronze-cast sill logs were not placed in situ until 1935. Paul V. Brown, who served as the Executive Secretary for the ILU, began soliciting bids for the construction work in early 1933. Edwin Pearson's New York City firm submitted a winning bid to manufacture a fireplace, hearth, and five logs for $5,400. The fireplace measured 10' x 4.5' x 5', and the hearth was 10' x 4.5'. Two of the sill logs were 20' x 8" x 9", one was 17'8" x 12" x6", and two were 3'7" x 16" x 6". They were manufactured in Munich by Pressmann Bauer & Company using the French sand method. [226]

To further memorialize the site, a 42' x 42' limestone wall and plaza with benches were added (Plate 2). The wall measures 1 foot, six inches thick by 4 feet, six inches in height and is constructed to enclose the cabin site. The wall and plaza were meant to enhance the cabin site. Another element was a large bronze sign that explained the memorial in Hibben's words. It read:

This symbol of the sills and hearthstone of a pioneer cabin is placed here to mark and set aside this bit of Indiana soil as more hallowed than the rest. Here lived for a time, Abraham Lincoln, and here died his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. For countless generations mankind has held the hearthstone as the altar of his home, a place of joy in the times of his prosperity, as a refuge in adversity; a spot made sacred by the lives of those spent around it. This is the hearth set here to mark the place where Lincoln at his mother's knee learned that integrity and strength, that kindliness and love of all beauty, which have made the memory of his life and work a priceless heritage to all the world. [227]

Such a display technique was common at many early twentieth century historic sites. The introduction of a wall, tower, or building to house an artifact, however, often overwhelms the artifact and distracts from its setting. Sites where this phenomenon can be seen include Lincoln's Birthplace in Hodgenville, Kentucky, where a small log cabin is located within a massive limestone, Greek Revival temple, or at Plymouth Rock, where the rock is located in a stone box approximately 5 feet below the viewing platform. [228] While the cabin memorial's limestone walls, plaza, and plaque are not as obtrusive as some examples, the wall serves to encapsulate a remnant of a single structure without reference to its surroundings. Prior to its removal, the Hibben plaque interpreted the site as a shrine to both Lincoln and the virtues he learned from his mother. A different interpretive approach was undertaken with the construction of the Memorial Building and Court.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE MEMORIAL BUILDING AND COURT (1938-1945)

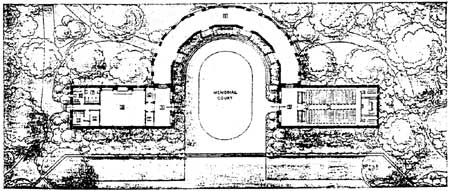

The ILU members proposed the Memorial Building and Court as an anchor for visitor activities. In 1931, Thomas Hibben offered an elaborate design consisting of a 150-foot tower and a pipe organ, but by May 1939, his scheme was deemed to be inappropriate. Initial plans also considered locating the Memorial Building close to Nancy Lincoln's grave, but this idea, too, was discarded. Therefore, Colonel Richard Lieber, president of ILU, sought the advice of Olmsted for both the building's design and its location on the completed landscape. Olmsted responded to the ILU in 1939 with five options that revolved around placing the building at various locations. The plan that was selected involved placement of two small buildings joined by a semi-circular cloister on the south side of the plaza, where a landscaped exedra was situated (Figure 23). [229]

|

| Figure 23: Allee and Plaza Site Plan, 1938-1944 (McEnaney, 2001: 27) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Plate 3: 1959 Photo of Cloister in Memorial Building |

In 1940, the ILU hired National Park Service architect Richard Bishop to finalize the plans for the Memorial Building and to supervise the on-site work. Bishop reviewed the many suggestions taken from ILU members and Olmsted and combined these with his own thoughts. Bishop's plan evolved out of the design ethic that proliferated during the New Deal era. The design's emphasis on native Indiana materials, use of local craftsmen, and simplified and stylistic Classical architecture are characteristic of Federal public works projects from the 1930s. The final design and construction included two buildings, the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall and Abraham Lincoln Hall, which were connected by a semi-circular cloister with five, life-sized, demi-relief sculptured panels depicting the life of Abraham Lincoln (Figure 24; Plate 3). The Nancy Lincoln Hall measured thirty feet by forty-five feet, and the Abraham Lincoln Hall measured thirty feet by sixty feet. Ground was broken in 1940, the cornerstone was laid in 1941, and construction was completed in 1943. The building was set back with a hierarchy of steps, and landscape designs emphasized its place within the landscape. Edson Nott, a landscape architect with the Indiana Department of Conservation, contributed to the final landscape designs and Indiana sculptor E.H. Daniels designed the five panels. As part of this project, the 1931 flagpole was relocated from the plaza to a terrace at the north end of the allee, and stone benches that originally were relocated at the cabin site memorial were moved to the corners of the plaza. Nott also prepared several plans for plantings and landscaping at the memorial, but these were implemented on an ad hoc basis. For example, a circular walk he planned for the north end of the allee was never constructed, and the present rectilinear configuration was in place by 1936. [230]

|

| Figure 24: Floor Plan of the Memorial Building (Outdoor Indiana, 1941: 1) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The sculptural panels and halls changed the symbolic character and interpretation of the site. Although the building was designated as the "Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Building," published descriptions of the site begin to change following its construction. Earlier newspaper articles described the site as "sacred soil" and the memorial as the grave of the "sainted mother." The introduction of the Memorial Building and Court was seen as a memorial to the lives of Nancy Hanks and Abraham Lincoln, as well as the time they spent in Indiana. During Governor Henry F. Schricker's commemoration of the site he described it as follows:

Surely we may feel that we are on sacred ground. It contains the mortal remains of Nancy Hanks Lincoln and it was pressed for fourteen years by the bare feet of Abraham Lincoln. From it grew the bread that formed his bones as a growing boy. Surely we may feel that we are in spirit associating here with Nancy Hanks and Abraham Lincoln. We are erecting here a shrine to Motherhood and to the family hearthstone. We are memorializing democracy and religion. Here we pledge ourselves anew to freedom and union, to the cause of popular government and the American way of life and refresh ourselves anew with the principles of life that formed our pioneers. [231]

Governor Schricker's comments indicate that the shrine was increasingly being viewed as a patriotic memorial. It was common in the post-World War I and Great Depression years for both the Federal government and private organizations to commemorate the spirit of America.

At the Lincoln memorial, this was manifested in part by the Federal government's increasing role in the site's preservation, which ultimately led to the initiation of a study in 1959 to determine if the park merited inclusion in the National Park system. Among the sites photographed for the 1959 report were the railroad tracks that passed through the park (Plate 4), Lake Lincoln (Plate 5), State Route 162, which accessed the park entry (Plate 6), the allee (Plate 7), and the Memorial Building (Plate 8). Both the railroad tracks and the road were felt to detract from the park's setting, even though both elements actually predated the park's existence. The railroad tracks were laid during the 1870s, while the state highway followed an alignment that dated to the early nineteenth century.

|

|

|

|

|

| Plate 8: 1959 Photo of Interior of Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Hall |

DESIGNATION AS A NATIONAL MEMORIAL

The 1959 study concluded that the park should remain under state ownership and control. The State of Indiana, however, recognized the status assigned to parks controlled by the National Park Service and spent the next two years lobbying for its designation as a national memorial. Congressman Winfield K. Denton was especially instrumental to persuading the National Park Service to reconsider its position. In 1962, these efforts were rewarded with the passage of P.L. 87-407, 46 Stat. 9 (P.L. 87-407), authorizing the establishment of the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. [232]

In June 1963, the State of Indiana transferred ownership of 114.49 acres to the Federal government. An additional fourteen acres were acquired the following year. Only twenty-five acres of this tract, however, were part of the original Lincoln farmstead. Once the boundaries of the memorial were established and transferred to the Federal government, the National Park Service considered several changes, many of which were never completed. Among the proposed alterations actually implemented were construction of a larger parking lot, paving of the walks that paralleled the allee as well as trails through the woods, and relocation of state highway 162, which extended between the allee and the Memorial Building. The Memorial Building was adapted for use as a visitor's center, which required enclosing the cloister and adding a wing to the south side of the structure. A maintenance area and employee housing were constructed to the west of the allee and an exhibit shelter was placed to the north. [233]

In 1968, a Living History Farm also was introduced to the interpretation program (Plate 9). This feature was representative of a nationwide effort undertaken by museum professionals who were dissatisfied with the static displays and dioramas that were found in most museums. Using "living history," museums sought ways to create a dynamic picture of a historic period. They trained interpreters in period customs, provided period dress and tools, and developed structures that were as historically accurate as was feasible. [234]

|

| Plate 9: View of Living History Farm |

The Living History Farm at the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial was developed by the National Park Service under the direction of the agency's director, George B. Hartzog, Jr., who wanted to develop a series of farms in national parks. This effort was separate from the 1960s-era joint venture involving the National Park Service, Department of Agriculture, and Smithsonian Institution to establish a nationwide system of living history farms. The addition of this feature to the park was not without controversy, as some officials felt that the living history farm would distract from the visitor's experience of the rest of the memorial. In its original conception, the farm also would have had a deleterious effect on other aspects; the 1970 Interpretive Prospectus proposed removing the cabin site entirely and relocating the Trail of Twelve Stones. Neither of these measures, however, was implemented. [235]

The Living History Farm was constructed using historic agricultural buildings from throughout Indiana. Each building was disassembled and moved to the park for reconstruction. Once in place, the buildings functioned as an outdoor museum with guides dressed in period costumes and performing typical chores of a nineteenth century farm. The farm continues to perform its educational mission to the present day.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/hrs/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003