|

Lower Delaware National Wild and Scenic River New Jersey-Pennsylvania |

|

NPS photo | |

Introduction

As the largest free-flowing river in the eastern United States, the timeless Delaware River flows through forests, farmlands and villages, and majestically links the most densely populated region in America with its storied past. The lower non-tidal portion of the Delaware River stretches 67 miles unbroken from south of the Delaware Water Gap to Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and serves as the boundary between the two states. Key segments that lie between the Water Gap and Washington Crossing, including three Pennsylvania tributaries, the Paunacussing, Tinicum and Tohickon Creeks, were designated into the National Wild and Scenic River system in 2000. The more developed industrial parts of the river corridor were excluded from consideration into the National System.

The lower Delaware River is situated within two hours drive of the New York City and Philadelphia metropolitan areas. By the time the river empties into the Delaware estuary, nearly 10% of the nation's population has tapped into it. These water diversions, coupled with increases in river corridor development and drought, have stressed the fragile shortnose sturgeon population, shad, great blue herons, ospreys, eagles and other threatened and endangered species. But through the partnership between the National Park Service, the two states, counties and local municipalities, the lower Delaware River's resources are better protected for the enjoyment of future generations.

Naturalists, river recreators and history buffs will find river activities to suit their interests. The lower Delaware River has something for everyone. Breathtaking scenic vistas of forested bluffs, farms, hamlets, undeveloped islands and 19th century canal buildings greet lower Delaware visitors and recreators. Along the shoreline, beavers work, otters frolic and white-tailed deer forage, while skyward, masses of migratory birds mysteriously follow their primordial paths along the Atlantic Flyway.

Fertile farm lands adjoin complex canal networks on both sides of the river. The river corridor's canals, mil1s and towpaths tell the story of a bygone era of water-borne commerce. Riverside villages and towns mark the routes of George Washington's ill-clad army during America's desperate struggle for independence. 19th-century bridges still connect towns along the Lower Delaware River's tributaries.

Today, locals and visitors alike fish for striped bass and shad, and gamefish like walleye pike and muskellunge thrill anglers of all ages. Recreational boaters, tubers and paddlers ply the lower Delaware's broad, calm waters. Picnickers and campers enjoy the solitude of riverside public parks, and birders wonder in amazement at the numbers and diversity of local and migratory birds that feed and nest along the river's banks, in its wetlands, and on its undeveloped islands. The lower Delaware River truly has something to offer to everyone.

Management Goals and Approach

The Lower Delaware River Management Plan provides a vision for the future of the river and context for future actions that emphasize local control and home rule. The heart of the vision is expressed in the following six management goals that were crafted by the Lower Delaware Wild and Scenic River Task Force prior to national designation.

Goal 1: Water Quality. Maintain existing water quality in the Delaware River and its tributaries from measurably degrading and improve it where practical.

Goal 2: Natural Resources. Preserve and protect the river's outstanding natural resources, including rare and endangered plant and animal species, river islands, steep slopes and buffer areas in the river corridor and along the tributaries.

Goal 3: Historic Resources. Preserve and protect the character of historic structures, districts and sites, including landscapes, in the river corridor.

Goal 4: Recreation. Encourage recreational use of the river corridor that has a low environmental and social impact and is compatible with public safety, the protection of private property and with the preservation of natural and cultural qualities of the river corridor.

Goal 5: Development. Identify principles for minimizing the adverse impact of development within the river corridor.

Goal 6: Open Space Preservation. Preserve open space as a means of maximizing the health of the ecosystem, preserving scenic values, and minimizing the impact of new development in the river corridor.

A cooperative approach to management is envisioned with the National Park Service and the existing Delaware River Greenway Partnership, assisting the existing institutions and authorities and local communities with the implementation of the plan and outreach to the public.

Wild & Scenic River Background

In the 1960s, the country began to realize that our rivers were being dammed, dredged, diked, diverted and degraded at an alarming rate. To lend balance to our history of use and abuse of our waterways, Congress created the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. In October of 1968, the freshly penned Wild and Scenic Rivers Act pronounced,

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural and other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations. The Congress declares that the established national policy of dams and other construction at appropriate sections of the rivers of the United States needs to be complemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof in their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes.

The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System now protects many of the rivers of our history, our literature, and our nation's youth. John Muir's Tuolumne River and his famous, losing battle to stop the flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley; Zane Grey's famous flyfishing river the North Umpqua; and the Missouri of Lewis and Clark's journeys. Great rivers from our past, now guaranteed to be great rivers in our future.

Designation as as wild and scenic river is not designation as a national park. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act does not generally lock up a river like a wilderness designation. The idea is not to halt development and use of a river; instead, the goal is to preserve the character of a river. Uses compatible with the management goals of a particular river are allowed; change is expected to happen. Development not damaging to the outstanding resources of a designated river, or curtailing its free flow, are usually allowed. The term "living landscape" has been frequently applied to wild and scenic rivers. Of course, each river designation is different, and each management plan is unique. But the bottom line is that the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System is not something to be feared by landowners.

The benefits of Wild and Scenic River designation are numerous. First, because designation provides sustained staff support and a modest budget for conservation work, new information about river's important resources are collected and made available for local use. Designation also helps unite communities and state government as they tackle regional water quality, flow protection, recreation management and land conservation issues. Finally, the river management plans can help guide decisions by agencies, municipal governments, conservation organizations and landowners as they work to protea a valued community resource.

Outstandingly Remarkable Resources

The lower Delaware River possesses a great diversity of significant resources. A high density of population and recreational opportunities combine with a wealth of natural, cultural, and historic features of national significance.

Natural Resources

The lower Delaware River corridor is filled with dramatic contrasts. High, rocky gorges, steep bluffs and dry ridgelines contrast in sharp relief with dense forests, wetlands, and river islands, producing diverse and unique landscapes within a relatively small geographic region.

Four geologic provinces running in a generally east-west direction shape the Lower Delaware River corridor's varied landscapes. The topography of the northern end of the corridor is broken by rocky and mountainous terrain. The middle river corridor is comprised of hills and clay soils, which contrast markedly with the southernmost province — the flat, marshy coastal plain.

Cliffs as high as 400 feet above the valley floor provide a desert-like environment for the eastern red cedar. At Milford Bluffs, in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, Prickly Pear can be found, as well as he endangered Green Violet and Smooth Veiny Peavine Rare northeastern U.S Roseroot, an arctic-alpine herb, grows on shelves and in crevices at Pennsylvania's Nockamixon Cliffs — the plant's southernmost reach.

Lush areas willow, spirea, silk dogwood and alder shrubs can be found in the river corridor's floodplain. This riverside vegetation provides valuable habitat for birds, mammals. and shades the water for fish. The riverside vegetation varies correspondingly with the geology and soils in the river corridor. In the upper reaches large-toothed aspen and gray birch can be found. Throughout most of the river corridor area, red maple, red oak, walnut, black cherry, sycamore and hemlock trees are present.

The many land and vegetation communities of the lower Delaware River corridor not only provide for diverse landscapes, but also provide diverse habitats for fish and wildlife.

Wildlife diversity is inextricably linked to habitat diversity in the lower Delaware River corridor. Dependent on river corridor habitats and fisheries are mammals. reptiles and amphibians — some of which are listed as threatened or endangered. Among mammals, white-tailed deer populations have increased dramatically in the latter 20th century, nearly to the point of threatening certain plant species and the herbivores dependent upon them. Beaver and river otter are active along he Delaware, and four threatened bat species — Keen's, Small-footed, Northern Long-eared, and Indiana — inhabit the river vicinity in Upper Bucks (PA) and Hunterdon (NJ) counties. Reptiles and amphibians such as bog turtles, coastal plain leopard and New Jersey chorus frogs can be found in wetlands, and serve as important links in the local food chain.

Dozens of varieties of spawning and resident fish are supported by the Delaware River. Resident species like smallmouth bass, channel catfish, hybrid muskellunge, bullhead. wh1te perch, and walleye pike thrive in the river. The river's tributaries maintain stocked trout. Due to improving water quality, large schools of striped bass, shad and herring are again making their seasonal, upstream migration to their spawning areas. The federally listed endangered Shortnose Sturgeon can be found in river segments between Philadelphia and Treton, and the globally rare At1ant1c Sturgeon swims as far upriver as Treton.

The skies above the river follow the Atlantic Flyway, one of the four major flyways through North America. Riparian forests and grasslands, particularly in floodplain wetlands and river islands, provide food and shelter for a variety of resident and migratory birds. Federally listed endangered Osprey and state listed Bald Eagle can be seen nesting atop riverside perches, and Peregrine Falcons inhabit the highest bluffs overlooking the Heron, Upland Sandpiper, Northern Harrier and Red-headed Woodpecker also inhabit the river corridor.

Historic Resources

For thousands of years before and after European settlement, the lower Delaware River served as a resource, linking people, ideas, and commerce. The Lenni Lenape fished, hunted and traded along the lower Delaware River corridor, long before Europeans arrived in the 17th century. The stories of the Lenni Lenape, immigrants, farmers, canal and millworkers can still be heard along the lower Delaware River. Visitors to the river w ill find history in every town, canal and towpath. The lower Delaware River's role in connecting people, ideas and commerce will emerge at every stop along the river's edge.

European settlers changed the landscape by clearing forests for agriculture, building mills to process grains, and to manufacture textiles and paper. Around these mills sprang towns like Lambertville, Stockton and Milford in New Jersey and New Hope, Riegelsville and Easton in Pennsylvania.

Through the summer and autumn of 1776, the Continental Army under George Washington suffered a string of defeats in New York and northern New Jersey, necessitating the army's retreat across the Delaware River to Pennsylvania. Faced with expiring enlistments and plagued by inadequate supplies, on Christmas Day, 1776, Washington led 2,000 troops in a bold crossing of the Delaware River. Early the next morning, the Continental Army attacked the surprised Hessian garrison. Nearly 1,000 Hessians were captured, along with their cannon and supplies.

Washington then returned to Pennsylvania. A week later he again crossed the Delaware River and struck Trenton. The next day, January 3rd, 1777, Washington gambled and attacked British regulars at Princeton — sending them in retreat to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, to wait out the winter.

Washington's resourceful use of the Delaware River, both as a moat to protect his troops and as a springboard to attack the enemy, buoyed the Continental Army and garnered the young nation new respect from France. The riverside towns experienced occupations by both armies, and the war left an indelible mark on regional culture — and American folklore.

By the early 19th century, the nation needed a better transportation network to transport goods, food, and fuel. By this time coal was replacing wood to fuel America's industrial production, and milled grains were in demand by nearby cities, that were experiencing tremendous growth. To improve commerce, the Delaware Canal, the Delaware and Raritan Canal, and the Morris Canal were built along the lower Delaware River. With the canals, Anthracite coal could be transported from the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania to New York City and Philadelphia.

Just decades after the canal was completed, transportation by rail replaced it. But the canals still exist, and at New Hope, Pennsylvania, and Stockton, New Jersey, and along the canal state parks, visitors can learn about an era of transportation that changed the river and the region. In 1988, Congress recognized the Delaware and Lehigh Navigational Canal National Heritage Corridor and the key role of the lower Delaware River's historic canals.

Scenic/Recreational Resources

The lower Delaware River and its tributaries are dotted with watercraft from innertubes to canoes and kayaks to pontoons, speed boats, and personal water craft. Hikers, joggers, and bicyclists crowd the canal paths and trails on both sides of the river. Fishermen, bird watchers, and naturalists seeking a serene landscape are drawn in great numbers. There are many state and local parks in the corridor. The Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park in New Jersey and the Delaware Canal State Park in Pennsylvania offer linear recreation corridors along the canals.

The river corridor also offers spectacular autumn foliage, dramatic natural ice sculptures in the winter, and spring's natural migration of birds. Beautiful views of the river and canals are complimented by the scenery of the historic riverside towns and mills. Both Pennsylvania and New Jersey have designated the routes that flank the river as scenic byways.

About Your Visit

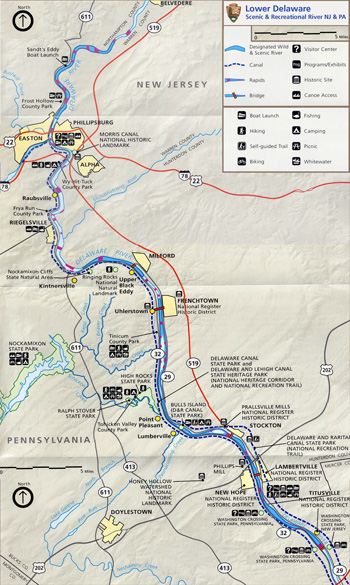

(click for larger map) |

To help ensure a safe and enjoyable trip on the lower Delaware and to the surrounding communities, the National Park Service strongly recommends that all river uses observe local laws and the following rules and regulations:

Fishing and Boating

Valid fishing licenses are required everywhere on the Delaware River. Special fishing regulations for the interstate waterway involving licensing, seasons, size, and creel limits should be obtained from State sources. Proper boat registration is required.

Safety

Always wear a properly fitted, Coast Guard-approved life jacket while boating, swimming, wading, or tubing on the river. A life preserver is useless unless you wear it. Guard against hypothermia by wearing protective clothing when the water is cold. Even in late spring when the air temperature is warm, the water is still frigid. Loss of body heat is 25 times greater in cold water than in air of the same temperature. Wear a wetsuit or clothing made of wool or propylene. If you go on the river, you should know how to swim.

Never canoe alone. A minimum of two canoes is recommended, with one as lead canoe and another as sweep or drag canoe. Stay in view, but keep a safe distance between canoes. If you capsize, keep upstream from the craft. A current of 3 mph can hold a swamped canoe against a rock with a force of more than a ton. If conditions worsen and you must leave your canoe, float with your feet pointed downstream and near the surface, to cushion yourself against large rocks and to prevent a foot or leg from getting caught on submerged branches or between rocks.

Carry a throw line and first aid kit with you. Do not drink alcoholic beverages before or during boating. Alcohol consumption and drug abuse have contributed to many drownings. Tie a plastic bag into the boat, and carry out your trash. Guard again sunburn with sunscreens and appropriate clothing.

More Information

Most towns along the river are small with varying degrees of visitor services. New Hope, Lambertville, Stockton, Frenchtown, Milford, Easton, Phillipsburg, and Belvedere are the most developed portions of the river with a range of visitor facilities.

Source: NPS Brochure (undated)

|

Establishment Lower Delaware National Wild and Scenic River — November 1, 2000 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Annual Report: 2020

Historic Site Master Plan & Feasibility Study: Lock 2 East of the Morris Canal (HJGA Consulting, February 4, 2008)

Junior River Ranger Activity Booklet, Lower Delaware National Wild and Scenic River (2014; for reference purposes only)

Lower Delaware River Management Plan (undated)

Lower Delaware River National Wild & Scenic Info Sheet (2021)

Lower Delaware River National Wild & Scenic River Study Report (1999)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Frenchtown Historic District (Ellen Fletcher, July 31, 1993)

Lambertville Historic District (David Gibson and Steven Bauer, rev. James Amon, November 1, 1980)

Historic Resources of New Hope Borough (Ann Niessen and Stephen G. Del Sordo, September 13, 1984)

Titusville Historic District (David Gibson and Steven Bauer, rev. Candace Peck and Terry Karschner, November 1980)

The First Fifteen Years: Accomplishments of the Lower Delaware National Wild & Scenic River Program: 2000 to 2014 (April 2015)

lode/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025