|

LONGFELLOW

Papers Presented at the Longfellow Commemorative Conference April 1-3, 1982 |

|

LONGFELLOW, HIAWATHA AND SOME 19TH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTERS

By Rena N. Coen

Dr. Coen received her Ph. D. at the University of Minnesota, where her dissertation topic was "The Indian as the Noble Savage in Nineteenth Century American Art." She is the author of numerous books and articles on American art both for adults and children, and is presently Professor of Art History at St. Cloud State College, St. Cloud, Minnesota.

When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow began to write Hiawatha in June of 1854, he was giving expression to an idea that had been in his mind for some time. He was also voicing an interest, common to the nineteenth century, in the fast vanishing Red Man, the savage but noble Indian of its plains and woodlands. In his literary and visual personification as a noble savage, the Indian represented for white America, a nostalgia for the past, a longing for a primitive innocence that embodied all that was good and pure in nature. Ultimately deriving from eighteenth century moral philosophy, especially but not exclusively that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the idea of the noble savage focused the social idealism and taste for exoticism of the age of enlightenment on the utopia which it thought it had discovered in the New World. Here corrupt governments and the evil ways of European society had not yet interfered with the natural order. Here, that child of nature, the savage Indian, could live out his life in innocent virtue and in simple harmony with his primitive surroundings. By the mid-nineteenth century, this idealized savage had become a familiar figure in American literature and art. James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, on the one hand, and George Catlin and Seth Eastman on the other, are examples of a symbiotic relationship between the written and the painted word as it focused on images of the native American. In these artists, and others, the Indian represented the return to nature, the admiration for simple virtues, and the interest in the remote, the sentimental and the picturesque, all of which constitute a current of thought and feeling that is summed up in the term, romanticism.

Longfellow, as a poet and man of letters, sensitive to the cultural nuances of his time, could hardly have been unaware of the romantic interest in the noble savage that forms such an important component of the intellectual atmosphere of his time. He was well read, and, in a mild, gentlemanly way, was interested in art and artists. [1] It was their descriptions that supplied him with the setting of The Song of Hiawatha, for Longfellow himself never visited the upper Midwest and the locale of his poem. And, as far as his interest in the Indians was concerned, that had begun as early as his college years, when, under the date of November 9, 1823 he had written to his mother that he had just read the Rev. John Heckwelder's Account of the History, Manners and Customs of the Indian Nations of Pennsylvania and the Neighboring States. He remarked that, paradoxical as it might seem, he believed that the Indians were "a race possessing magnanimity, generosity, benevolence and pure religion without hyprocrisy." [2] This impression was strengthened and his interest quickened is reading of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's Algic Researches in 1839. [3] It was from Schoolcraft that Longfellow learned the legends of the Iroquois on which The Song of Hiawatha as based. In the poem the tribal legends are transferred from the Iroquois to the Ojibway of Saulte Ste. Marie and Lake Superior because Schoolcraft himself was more familiar with that particular group of Indians. [4] It was, of course, both Longfellow's and Schoolcraft's hope that their images of the Indian as nature's hero would compel a change in the superficial Indian stereotypes still prevalent in the popular mind—that of the Indian as a bloodthirsty savage always looking for a white man's scalp. Their deeper knowledge of Indian character and customs led to a mutual admiration and respect, and in 1856, encouraged by the immediate success of The Song of Hiawatha, Schoolcraft reissued his Algic Researches in an expanded edition with a new title: The Myth of Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythological and Allegoric, of the North American Indians. The volume was dedicate to Longfellow.

In view of Longfellow's relationship with Schoolcraft and his acknowledged debt to Schoolcraft's writings, it is interesting to note Schoolcraft's relationship in turn to Seth Eastman, soldier, artist, and commandant of Fort Snelling in the Minnesota Territory in the 1840's. Trained at West Point, where he later returned to teach art, Captain Eastman was a landscapist in the tradition of the Hudson River School when he arrived at Fort Snelling in 1841. There he began to paint the Sioux Indians of the area for military affairs as this frontier outpost left him plenty of time to indulge his passion for paintings and drawing. Indeed the seventy-five or more oils and scores of drawings and water colors constituted one of the most important bodies of pictorial documents on Indian life at that time. It made Eastman Schoolcraft's choice for illustrating his monumental work on the Indian tribes of the United States, commissioned by Congress in 1847. [5] In a letter of June 30, 1854, Schoolcraft wrote to Charles E. Mix, Acting Commissioner for Indian Affairs, that Captain Eastman's "peculiar fitness . . . for the work arises from his skill and talent as an artist which is believed to be superior to any other within my knowledge. His long service on the frontier . . . enables him to apply his skill to the particular manner and customs and arts of the Indians with a truthfulness which a strange artist, whatever his talents, could not do." [6] Eastman received the commission, was temporarily relieved of his other army duties, and completed the oils, water colors and drawings which were engraved for Schoolcraft's book.

Eastman, as Schoolcraft's illustrator, and therefore one indirect source for Longfellow's visual image of the Indians, is important in another connection as well. Mary Henderson Eastman, his wife, was among the first to write down the legends of the Indians during the time she spent on the Minnesota frontier with her husband in the 1840's. Her first book on Indian lore, Dahcotah; or Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling, was published in New York in 1849. [7] This and subsequent collections of Indian legends were illustrated by her husband, some of the illustrations using the same plates that were engraved for Schoolcraft's work. And though a direct connection between Mary Eastman and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow has yet to be discovered, the mere coincidence of both of them writing about Indian legends within a five year period, and the connection of each of them in turn with Schoolcraft, points to a strong probability that they were, at least, aware of each other. [8]

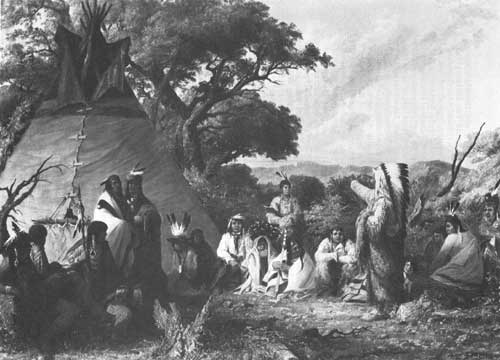

In any event, a number of Eastman's works reproduced in Schoolcraft's book may well have served as visual models for the poet. The nineteenth century was, in fact, a period when literature and art were closely tied, writers frequently describing scenes in precise pictorial terms and artists often painting in a literal and descriptive manner. Thus, for example, Eastman's Indian Council (Figure 6), engraved as Plate 27 in Volume II of Schoolcraft's work, sets the stage, so to speak, for Longfellow's description of Hiawatha counseling his people. Ceremonially dressed in his feathered bonnet and wrapped in a great fringed robe, Eastman's hero seems to be declaiming with the same sense of solemn dignity typical of Hiawatha's addresses to his people.

|

| Figure 6. Indian Council by Seth Easthman (1808-1875), 1840's. Oil on canvas. The Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma. |

The famous tribal council in Longfellow's poem in which Hiawatha preaches unity among the warring tribes: "All your strength is in your union, / All your danger is in discord" is actually laid in the Pipestone Quarry country of western Minnesota, painted by George Catlin in 1835 (Figure 7). The Indians associated this area with the coming of peace for the calumet, or peace pipe, was fashioned from the soft, reddish stone quarried there. Catlin, the great painter of Indians, had visited Pipestone and its sacred quarrying ground in the summer of 1835, one of the first white men permitted to do so. He not only painted it, but described it in some detail in his own monumental work on the Indian tribes of North America which was published in 1841. [9] From the description of the quarry alone, one gets the clear impression that Longfellow was familiar with Catlin's book as well as with Schoolcraft's.

|

| Figure 7. Pipestone Quarry, on the Coteau des Prairis by George Catlin (1796-1872), 1836. Oil on canvas. 19-1/2 x 27-1/4 inches. National Museum of American Art (formerly National Collection of Fine Arts), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.; gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison. |

There are other similarities as well between Longfellow's and Catlin's images. The monumental portrait of Mah-toh-to-pa, or Four Bears (Figure 8), second chief of the Mandan Indians among whom Catlin spent the winter of 1834, is the very model of picturesque and savage nobility. It aptly fits the description of the young Hiawatha about to leave the lodge of his grandmother, Nokomis, to seek his father, Mudjekeewis:

From his lodge went Hiawatha,

Dressed for travel, armed for hunting;

Dressed in deer-skin shirt and leggings,

Richly wrought with quills and wampum;

On his head his eagle-feathers, . . .

In his hand his bow of ash-wood,

Strung with sinews of the reindeer;

|

| Figure 8. Four Bears, Second Chief by George Catlin (1796-1872), 1832. Oil on canvas, 29 x 24 inches. National Museum of American Art (formerly National Collection of Fine Arts), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison. |

In both the poetic and the painted images the emphasis is on strength, courage and the colorful and primitive natural man.

If the paintings of Catlin and Eastman were among the many influences on the imagery of Longfellow, the poet, in turn, especially after The Song of Hiawatha was published in 1855, exerted at least as strong an influence on two generations of American artists. Sometimes this influence was direct, in the sense of inspiring visual artists to attempt a portrayal of Hiawatha or to illustrate various passages from the Longfellow poem. Frequently, however, the influence was less tangible, leading not to visual quotations from the poem but rather to a desire to visit its locale and to record its scenery and its native inhabitants. Thus, from about 1855 to about 1885 the steamboat trip on the upper Mississippi River became a popular tourist pilgrimage, important for artists as well as for pilgrims of other talents. [10] The route went past Winona and Maiden Rock (from which, it was said, the Indian maiden, mother of Hiawatha, had thrown herself into the river far below) to the Falls of Minnehaha. [11] Among the artist pilgrims was John Kensett, who first visited the area in 1854, the same year that his friend Longfellow began to write The Song of Hiawatha. As a product of his visit he painted, in 1856, a view of Lake Pepin, a widening of the Mississippi River above the town of Winona, and also, possibly, a view of Minnehaha Falls as well (Figure 9). Though some question has been raised as to the identity of the latter picture, for the falls seem narrower and steeper than in other representations of them, nevertheless, an inscription on the verso of the frame in Longfellow's own hand reads: "Waterfall by Kensett, 1856." In view of the date, and also the fact that of the many paintings of waterfalls by Kensett, it was this particular one that the artist presented to his friend, the author of Hiawatha, I am inclined to believe that the Falls are correctly identified as Minnehaha. It is possible that Kensett, using perhaps quick sketches of the site made during his visit to it, merely excercised artistic license and deliberately exaggerated some aspects of the scene in order to dramatize its "wilderness" locale.

|

| Figure 9. Waterfall by John Kensett (1816-1872), ca. 1856. Oil on prepared board, 11-3/4 x 9-3/8 inches. National Park Service, Longfellow National Historic Site, Cambridge, Massachusetts. |

There were many other artists who made similar trips up the mighty Father of Waters "to the forests and the prairies and the great lakes of the Northland," finally reaching their destination at the Falls of Minnehaha, those laughing waters that:

Flash and gleam among the oak-trees,

Laugh and leap into the valley . . . .

Gleaming, glancing through the branches,

As one hears the Laughing Water

From behind its screen of branches?

Among these artists certain names stand out. They include Alfred T. Bricher, who got at least as far as Red Wing in 1856, and Ferdinand Reichardt, who painted the steamboats on the upper Mississippi in 1857. Others who painted the falls celebrated in Hiawatha include Gilbert Munger in 1860, Robert Duncanson in 1862, Jerome Thompson in 1870, Joseph Meeker in 1879 and Albert Bierstadt in 1886.

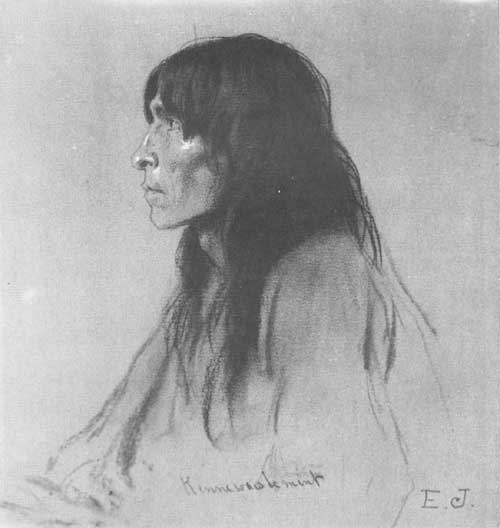

In the case of at least one young friend of the poet, Eastman Johnson, who, in 1846 had been engaged by Longfellow to draw portraits of himself and his family, the romantic appeal of the Hiawatha legend resulted in a trip to Minnesota in the summer of 1856 and a long sojourn there through the following winter. Johnson's brother and sister lived in the Duluth-Superior area, but one feels that it was more than family sentiment that drew the artist to this pioneer settlement. For, in 1857 Johnson travelled 150 miles beyond Duluth to the upper reaches of Lake Superior to live among the Ojibway along the shores of "Gitchee Gumee." At the village of Grand Portage, he drew their portraits, their settlements and their way of life (Figure 10). His series of drawings done in crayon and charcoal are striking studies of a proud and dignified people, vivid embodiments of the noble savage and typical of both Longfellow's and Johnson's image of idyllic primitivism. Their combination of the real and the ideal follow closely, in fact, on the poet's own analysis of the two schools of thought which he discerned in contemporary poetry, the "Ideal and the Actual." "The first," wrote Longfellow, "endeavors to invest ideal scenes and characters with truth and reality; the second, on the contrary, clothes the real with the ideal, and makes actual and common things radiant with beauty." At the same time he felt that simplicity and directness were also required for "every work of art should explain itself." If it required commentary, it had failed as a work of art. [12] Just so do the Johnson drawings fit into Longfellow's esthetic criteria for they are honest, direct, and able to "make actual and common things radiant with beauty." It is interesting that Johnson felt a particular attachment to these drawings for he kept them for himself, and though he showed them to friends, he never exhibited them during his lifetime.

|

| Figure 10. Kenne Waw Be Mint by Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), 1956-1857. Charcoal on paper, 8 x 8 inches. St. Louis County Historical Society, Duluth, Minnesota. |

There were, of course, artists who addressed the Hiawatha theme directly, not as an excuse for scenic paintings of the Falls of Minnehaha or the Indians of Lake Superior, but for the Hiawatha subject itself. This was so even when the Hiawatha figure was treated subjectively as a personal symbol of the romance of primitive life. Thus, in Ralph Albert Blakelock's Hiawatha (Shooting the Arrow) (Figure 11), a standing figure is seen drawing on a bow, as he emerges from the darkness of an undifferentiated background. The Indian, nude except for loin cloth and moccasins, is vague, but still individualized. Like Eastman Johnson's images, it combines Longfellow's criteria for the ideal and the actual, for as has been aptly said, the Indian "is real enough, but he is also somewhat unreal, wrapped in the emotion of an ideal concept, very close indeed to the concept of the 'noble savage.'" [13]

|

| Figure 11. "Hiawatha" (Shooting the Arrow) by Ralph Blakelock (1847-1919), 4th qtr. 19th century. Oil on canvas, 8-3/16 x 6-3/16 inches. Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts. |

Blakelock's painting entitled There Was Peace Among the Nations (Figure 12) seems close to Hiawatha in terms of the literary implications of the title. It shows a western scene in which two Indian women sit in the shade of an overarching tree. In the background figures move about among the tepees of an encampment. Nothing else happens. The Indians exist in a remote, romanticized setting that has more to do with a remembered dream than it does with ordinary life. This impression is heightened by the passivity of the women, the empty space of so much of the foreground, and the deep recession to a vast and distant horizon. It is again a picture of the idyllic primitivism which the artist remembered, or thought he remembered, from his travels in the west as a young man. His admiration for Longfellow's poem merely invested that memory with a new immediacy.

|

| Figure 12. There Was Peace Among the Nations by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919), possibly the 1870s. Oil on canvas, 20-1/18 x 36-1/2 inches. The Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma. |

None of these painters were more imbued with the very spirit and soul of Hiawatha than Thomas Moran. From the time of its publication, The Song of Hiawatha was his favorite poem and its pictorial possibilities were more fully exploited by him than by any of his contemporaries. Its celebration of nature's nobleman amidst the scenic wilderness of his surroundings, its elements of myth and legend, its picturesque characters, both animal and human, led him, in the summer of 1860 to invade the haunts of its hero. On July 29th of that year, Moran began sketching by "the shores of Gitchee Gumee / By the shining big-sea water," less poetically known as Lake Superior. [14]

Moran's best known painting on the Hiawatha theme is a large oil entitled The Spirit of the Indian (Figure 13). Painted in 1869, it bears little resemblance to the actual home of the Ojibway described by Schoolcraft and sketched by Moran himself. Instead, like parts of Longfellow's poem, it conjures up a romantic fantasy in which towering crags and murky waters set the stage for dramatic action. It shows Hiawatha's arrival at the home of the great Pearl-Feather, Megissogwon, the Magician and spirit of wealth and wampum, who had, many years before, slain the father of Nokomis. The hero has steered his birch canoe through the waters infested with Megissogwon's guardian serpents:

The Kenabeek; the great serpents,

Lying huge upon the water,

Sparkling, rippling in the water,

Lying coiled across the passage, . . .

Breathing fiery fogs and vapors,

So that none could pass beyond them.

|

| Figure 13. Spirit of the Indian by Thomas Moran (1837-1926), 1869. Oil on canvas, 32-1/4 x 48 inches. Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa, Oklahoma. |

On the upland, above the beach appears the gigantic yet ghostly form of the Manito, the evil spirit, half hidden in the mountain mists:

Tall of stature, broad of shoulder,

Dark and terrible in aspect, . . .

Crested with great eagle-feathers,

Streaming upward, streaming outward.

Then, with "bow of ash-tree" ready, Hiawatha engages the magician in

. . . the greatest battle

That the sun had ever looked on.

That the war-birds ever witnessed.

The section in Hiawatha on the Pearl Feather seems to have held a special appeal for Thomas Moran for it is particularly rich in purple mists and brilliant sunsets. Such spectacular effects of fiery glory were a favorite motif of a painter who described the American West in precisely such terms. In 1875 Moran painted Fiercely the Red Sun Descending to portray the outset of Hiawatha's journey westward:

To the purple clouds of sunset.

Fiercely the red sun descending

Burned his way along the heavens,

Set the sky on fire behind him,

As war-parties, when retreating,

Burn the prairies on their war-trail; . . .

It was probably this painting, referred to in the Longfellow literature as "a sunset by Thomas Moran" that was used as an illustration in some later editions of Hiawatha. [15]

In the same year that he painted Fiercely the Red Sun Descending, Moran also began to work on a series of Hiawatha illustrations—about twenty wash drawings, that his brother, Peter Moran, undertook to reproduce as steel engravings. These engravings were intended as a subscription project, and, though it was never completed, the Morans had Longfellow himself on their subscription list. When the Aldine ran a picture from the series, that of Hiawatha's friend, Kwasind, the Strong Man, the editor remarked that "Moran has caught the spirit of the original—the wild and primitive feeling in which the old Indian traditions originated. His characteristic excellences—power and imagination—are represented as well as they can be without color, in which he excels. For what he is, he has no master in America." [16]

As a footnote to the relationship between the poet and contemporary artists, it is worth pointing out that in that same year of 1875, Moran sent his large and spectacular painting, The Mountain of the Holy Cross, to the Gallery of Elliot and Co. in Boston. There it was exhibited for several weeks with other western scenes Moran had recently completed. Longfellow may very well have seen it there and remembered it some years later when he wrote the sonnet, The Cross of Snow, memorializing his dead wife, Fanny.

Perhaps the best known of all the Hiawatha illustrators is Frederic Remington who, in 1890, was commissioned to execute twenty-two full page plates and nearly four hundred text drawings for the illustrated Edition of The Song of Hiawatha. The commission fulfilled a long standing ambition of the artist's for, as his wife wrote to Remington's uncle on Dec. 3, 1888, "Fred has just left for Boston . . . to see Houghton Mifflin and Co. about illustrating Hiawatha and hopes to make satisfactory arrangements. Ever since he has done any illustrating he has dreamed of doing that, and now he hopes he can." [17] The drawings were duly commissioned and they did much to establish the young artist's reputation, for the Illustrated Edition was enormously popular. It is even possible that Remington's drawings helped to give the poem the cherished place it holds in American literature.

The Death of Minnehaha (Figure 14) is the best known of the illustrations for the 1891 series. It is, besides, typical of Remington's style. Where Moran delighted in brilliant color effects and luminous, far receding landscapes, Remington concentrates on the telling of the story, using a sharp and linear style that is more suited than Moran's painterly one to an illustrator's purpose. The picture is direct, vivid and unambiguous. Minnehaha has succumbed to famine and fever and lies on her death bed. Hiawatha has returned from a desperate search for game in the forest, "empty handed, heavy hearted," and, with his snowshoes hanging above him, he sits at the feet of his beloved, his "lovely Minnehaha / Lying dead and cold before him." Around them hover the spectral forms of the ghosts of the departed who had appeared to Hiawatha previously to warn him of impending doom: Their prophecy is fulfilled for Hiawatha.

And his bursting heart within him

Uttered such a cry of anguish,

That the forest moaned and shuddered, . . .

With both hands his face he covered,

Seven long days and nights he sat there,

Speechless, motionless, unconscious

Of the daylight or the darkness.

|

| Figure 14. The Death of Minnehaha by Frederic Remington (1861-1909), 1888-1890. Photogravure, from an original Remington design. First published in the 1890 edition of The Song of Hiawatha (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin and Company). |

If Frederick Remington was the quintessential illustrator of The Song of Hiawatha, Albert Bierstadt, like Thomas Moran, was the painter of its scenic locale. Bierstadt's vast, panoramic landscapes of the American west include several smaller views of the land of Hiawatha. He painted Minnehaha Falls at least twice once as a regular studio piece and once, in 1886, as a gift to the young son of his friend and Minneapolis patron, Thomas Barlow Walker. This is a small sketch of the Falls painted with a looser brush and broader color areas than are usually found in the artist's more grandiose pictures of the West. Three year old Archie Walker, his patron's son, appears as a small straw hatted figure, at the foot of the Falls, facing away from us toward the tumbling waters. It is a casual, almost genre view of the site Longfellow made famous as the home of the Dacotah arrow maker and his beautiful daughter, Minnehaha.

The same genre quality characterizes Bierstadt's View of Duluth at the western tip of Lake Superior. By now the big sea water beyond the shores of Gitchee Gumee has shed its wilderness aspect and the shining waters lap instead at the feet of a prosperous pioneer town. There are no picturesque savages here roaming through dense, primeval forests evoking a sense of the remote, romantic West. Instead, there is a sense of everyday life that describes the real rather than the ideal. Nevertheless, the scene is illuminated in the bright sunshine of a new day that reflects the cheerful optimism of a pioneer community.

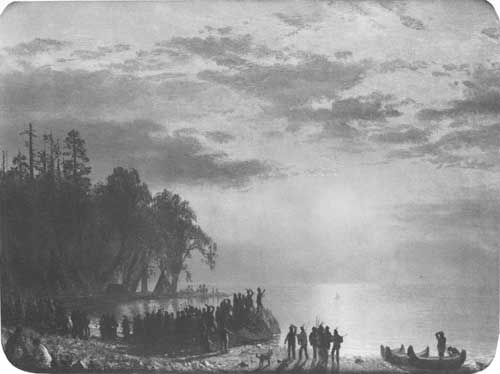

Another painting by Bierstadt, however, is a specific illustration for the Hiawatha story. The small oil painting, The Departure of Hiawatha (Figure 15) has a history that is unique in Longfellow's association with visual artists. On July 9, 1868, Bierstadt and his wife gave a dinner at the Langham Hotel in London in honor of Longfellow, who was also in England at the time to receive an honorary degree from Cambridge University. The dinner was a star-studded affair for the guests included a number of members of Parliament in addition to Robert Browning, Edwin Landseer, the Duke of Argyll and even Gladstone himself. After an elaborate feast that included corn as a compliment to the American guests and George IV pudding as a compliment to the English ones, speeches and toasts paid tribute to Longfellow and to Bierstadt himself. During the evening, Longfellow was given the small painting by Bierstadt of The Departure of Hiawatha. [18]

|

| Figure 15. The Departure of Hiawatha by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), ca. 1868. Oil on paper, 6-7/8 x 8-1/8 inches. National Park Service, Longfellow National Historic Site, Cambridge, Massachusetts. |

The painting is similar to Moran's pictures in its spectacular use of color. In a blaze of sunset, Hiawatha embarks in his canoe "On a long and distant journey, / To the portals of the Sunset." Bidding farewell to his people, Hiawatha,

Turned and waved his hand at parting;

On the clear and luminous water

Launched his birch canoe for sailing,

Sailed into the fiery sunset,

Sailed into the purple vapors,

Sailed into the dusk of evening.

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as the consequences of westward expansion became obvious, a new and bleaker view of the Indian began to prevail. Henry Farny, for example, one of the last visual recorders of Indian life as it was lived before the coming of the white man, undertook, like Moran and Remington, to illustrate the Hiawatha story. Only ten of the illustrations of a much larger project were ever completed. In one of them, By the Shores of Gitchee Gumee, Hiawatha is portrayed as a doomed hero. Wrapped in his own gloomy thoughts and with his back turned toward the observer, the Indian figure is small in the context of the painting emphasizing his vulnerability in the vast and limitless power of nature. As in Remington's picture, Farny's ink wash technique creates a sharp contrast of light and shadow and the suggestion of dreary coldness achieves an effect of sad resignation. The image is far indeed from the proud and stalwart Indians depicted in the earlier part of the century by Eastman Johnson or George Catlin. Like some of Farny's other Indian paintings which bear such titles as End of the Race or In The Valley of the Shadow, By the Shores of Gitchee Gumee symbolizes the end of the noble savage and white America's awakening to the realization that the romantic dream of a primitive idyll no longer existed in the frontier west.

One final picture completes the story of 19th century artistic response to Longfellow's poem. This is Thomas Eakins's oil study of 1874 entitled Hiawatha (Figure 16), Here the tragedy of Indian life is suggested by the isolation of the figure in a landscape that is bare and featureless except for the cloud formations that march across the picture plane, vaguely assuming the animal forms of the Indian's primeval environment. The dispirited pose of the figure suggests his loneliness and dejected retreat into his own somber thoughts. Though he is identified as Hiawatha in the title, the Indian is portrayed as a simple human form, without feathers, beads or fringed garmet. Without the identifying elements of Indian costume, he is, therefore, Everyman. Moreover, seen from the back facing inward, he pulls the spectator, too, into the picture, forcing him thus to participate in the final drama. It is as though neither the Indian hero nor the white artist can bear to confront us directly with the end of Indian life and the vanished idyll of the American West.

Then a darker, drearier vision

Passed before me, vague and cloud-like;

I beheld our nations scattered,

All forgetful of my counsels. . . .

Saw the remnants of our people

Sweeping westward, wild and woful,

Like the cloud-rack of a tempest,

Like the withered leaves of Autumn!

|

| Figure 16. Hiawatha by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), ca. 1874. Oil on canvas, 14-1/8 x 17-5/8 inches. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. |

NOTES

1 Longfellow counted many visual artists among his friends. He was also involved in a minor way with the art establishment of his day. When the first exhibition of the New England Art Union opened on Tremont Row in 1852, he was included among the vice presidents. See Neil Harris, The Artist in American Society (George Braziller: New York, 1966), p. 278.

2 Quoted in Albert Keiser, The Indian in American Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1933) p. 190. See also Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Algic Researches, Comprising Inquiries Respecting the Mental Characteristics of the North American Indians New York, 1839).

3 Keiser, The Indian in American Literature, p. 191.

4 Charles S. Osborn and Stellanove Osborn, Schoolcraft, Longfellow and Hiawatha (Lancaster, Pennsylvania: The Jacques Cattrell Press, 1942), p. 11.

5 Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, 6 Vols. (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co., 1851-57).

6 John Francis McDermott, Seth Eastman, Pictorial Historian of the Indian (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), p. 83, n. 17

7 Mary H. Eastman, Dahcotah; or Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling (New York: John Wiley, 1849).

8 Mrs. Eastman's later works on Indian life and legends, illustrated by Seth Eastman, included, The Romance of Indian Life, With Other Tales, first published by The Iris in 1852 as An Illuminated Souvenir, and subsequently reissued by Lippincott, Grambo and Co., Philadelphia, in 1853, The American Annual, Illustrative of the Early History of North America, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, n.d., and Chicora, and Other Regions of the Conquerors and Conquered, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co., 1854.

9 George Catlin, North American Indians, Being Letters and Notes on Their Manners and Customs, Written During Eight Years Travel Amongst the Wildest Tribes of Indians in North America, 2 Vols. Edinburgh: John Grant, 1841.

10 See Rena Neumann Coen, Painting and Sculpture in Minnesota, 1820-1914 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976), Ch. IV, "Tourists and Travelers", pp. 32-50.

11 Though the original Indian name was "Minnehaha" (Laughing Waters), the white settlers called the Falls "Brown's Falls" (probably for Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown) as early as 1823, and also "Little Falls". By 1852, however, they too were calling the Falls by the Indian name, "Minnehaha". See John Francis McDermott, "Minnesota 100 Years Age," Minnesota History (Autumn, 1952), p. 112.

12 Edward Wagenknecht, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Portrait of an American Humanist (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 106.

13 Norman Geske, Ralph Albert Blakelock, 1847-1919 (Lincoln: Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, 1975), p. 15.

14 Moran was traveling in the company of Isaac N. Williams, a portrait painter and later landscape painter. See Thurman Wilkins, Thomas Moran, Artist of the Mountains (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), pp. 29-30.

15 Newton Arvin, Longfellow, His Life and Works (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1963), p. 172.

16 Wilkins, Thomas Moran, p. 55. The set of Hiawatha drawings proved very popular. In 1876 six of them were exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and in 1882 the series was shown at the Bromley Art Gallery in Bradshawgate, near Bolton, England where Thomas Moran and his wife were visiting that summer.

17 Harold McCracken, The Frederick Remington Book, A Pictorial History of the Old West (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1966), p. 89.

18 Gordon Hendricks, Albert Bierstadt, Painter of the American West (New York: Harry N. Abrams and Fort Worth, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1974), p. 182.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

symposium82/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 23-Nov-2009