|

Lowell National Historical Park Massachusetts |

|

NPS photo | |

Lake Winnepesaukee combines with the Pemigewasset River high in the White Mountains of New Hampshire to form the Merrimack River. One hundred and ten miles long, the Merrimack drops ninety feet in elevation over its final forty-eight mile course through northern Massachusetts to the city of Newburyport on the Atlantic. Over a third of the river's drop in elevation occurs near its junction with the Concord River at a one-mile stretch known as the Pawtucket halls. It is here that the city of Lowell would eventually grow.

Before the arrival of white settlers, the Pawtucket Falls area served the Pennacook Confederacy, a group comprising the Pennacook, Pawtucket, Wamesit, Nashobah, and Souhegan tribes. In the spring, the area was rich in its supply of fish, and it became an annual tradition for the tribes of the Confederacy to meet at the falls, and while doing their yearly fishing, attend to tribal affairs.

The Indian way of life was maintained until the seventeenth century when white settlers first appeared in the area. Pennacook leaders were soon converted to Christianity, and the Indians were granted a parcel of land known as Wamesit for their own use in 1653. As relations with the whites deteriorated, however, the fortunes of the Pennacooks did as well. Wannalancit, Chief of the Confederacy, turned Wamesit over to the English in 1686, and the Pennacooks left their traditional homeland for more hospitable land in Canada.

Wamesit became known as Chelmsford Neck and was incorporated into the town of Chelmsford in 1725. By the nineteenth century, development of the area had proceeded at a slow pace, and the section of town now known as East Chelmsford consisted of a dozen or so family farms, a few grist mills and saw mills, a woolen mill, and, not insignificantly, the Pawtucket Canal.

Shipbuilders and merchants from Newburyport, incorporated as the Proprietors of Locks and Canals on Merrimack River, one of the nation's earliest corporations, began work on the Pawtucket Canal in 1792. When completed in 1796, the canal bypassed Pawtucket Falls and increased the flow of timber and agricultural products from New Hampshire to the sea. The canal's early success, however, was short lived. When the ship-building industry at Newburyport fell upon hard times after 1815, traffic on the Pawtucket Canal decreased with the dwindling demand for New Hampshire timber. In addition, the Middlesex Canal, which was completed in 1803, linked the upper Merrimack with the Charles River and diverted much of the Pawtucket Canal's trade from Newburyport to the larger market at Boston.

THE NATIONAL SETTING

The Middlesex Canal was well under construction when Thomas Jefferson became president in 1803. It was a time when America's economy was predominantly agricultural. Jefferson, like many of his countrymen, felt that America's strength lay in its agricultural heritage, and that industrialization, as evidenced by the squalor of European industrial cities, was morally reprehensible. Nevertheless, he modified his views in the following years and came to the rather Hamiltonian conclusion that a certain amount of industrial development was required to maintain economic independence from Europe. This change in attitude came at a time when a curtailment of trade with Europe had sharply reduced the amount of manufactured goods in America. Recognizing the need for such products, Jefferson and his followers decided that the objectionable aspects of the European industrial experience could be avoided by the dispersal of manufacturing centers throughout the American countryside.

FOUNDING FATHERS

It was under these conditions that Francis Cabot Lowell, a Boston merchant, travelled to England and Scotland in 1811. He toured British textile factories and was impressed with the advanced state of English technology, though he was also deeply affected by the impoverishment of the working classes. Lowell returned to America hoping to perfect his own power loom, with the intention of using it in a factory system of his own. His plans for the power loom, based on his observation of English looms, were developed in 1813 by mechanic Paul Moody. The power loom proved to be a major innovation in American textile manufacture, since it made possible the transformation of raw cotton into finished cloth within a single factory.

The need for the large amounts of capital required to finance the project came at a time when American merchants were frustrated by Jefferson's embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812. Businessmen were looking for new areas of investment. Lowell found willing investors in the "Boston Associates," a group of businessmen that included Lowell's fellow merchants, Patrick Tracy Jackson and Nathan Appleton. The group formed the Boston Manufacturing Company and began their operation on the Charles River at Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1815.

After Lowell's death in 1817, Jackson and Appleton continued to guide the growth and development of the Boston Manufacturing Company. Jackson, Lowell's brother-in-law and the company's largest stockholder, assumed company leadership. Appleton oversaw the sale of company products. Eventually, he would become a prominent spokesman for the textile industry, and as a congressman (1831-33), would work for the passage of higher tariffs, which, when passed, protected the growing industry from foreign competition.

The Waltham experience proved the viability of Lowell's manufacturing system. The physical limitations at Waltham. however, prompted Lowell's associates to look elsewhere for a site with a greater source of power—a source they would discover at East Chelmsford.

A PLANNED INDUSTRIAL COMMUNITY

"Our first visit to the spot was in the month of November, 1821 and a slight snow covered the ground. The party consisted of Patrick T. Jackson, Kirk Boott, Warren Dutton, Paul Moody and myself. We perambulated the grounds and the remark was made that some of us might live to see the place contain twenty thousand inhabitants. At the time there were, I think, less than a dozen houses on what now constitutes the city of Lowell..."

Nathan Appleton

from Introduction of the Power Loom and Origin of Lowell, Lowell,

1858.

Within a year after they gathered at East Chelmsford in this scene described by Appleton, the "Boston Associates" had acquired the four hundred acres lying between the Pawtucket Canal and the Merrimack and Concord Rivers by purchasing the controlling stock of the Proprietors of Locks and Canals. When the Merrimack Manufacturing Company was chartered in 1822, East Chelmsford witnessed the rapid construction of textile mills and a series of new power canals under the supervision of the agent of the "Boston Associates," Kirk Boott. Boott's role in turning a farming community into a model manufacturing center cannot be overstated: he dictated company policy, controlled the lives of his employees, and played a major role in the early town planning. Growth of the community was nothing short of spectacular. By 1826, construction of new mills was continuing unabated as the former agricultural village grew into a town, renamed Lowell, consisting of over twenty-five hundred residents. Ten years later, Lowell became the third city incorporated in Massachusetts. The new city, at that point, had a population of seventeen thousand and included eight major textile mills employing seventy-five hundred workers.

THE CANAL SYSTEM

Lowell's future was dependent on the efficient utilization of water power. The system of power canals constructed between the Pawtucket Canal and the Merrimack and Concord Rivers used the power of Pawtucket Falls to provide each company with the power required to run the machinery in their mills. The first mills were built along the Merrimack River and the Merrimack Canal in order to make maximum use of the "head" force generated by the river's drop in elevation. Later mills were served by additional canals.

Having purchased the controlling stock of the Proprietors of Locks and Canals, the Boston investors reorganized the company in 1825. The company was granted ownership of the canals and their power, and was put under the supervision of Paul Moody.

In 1837, James B. Francis became chief engineer, a position he held for forty years. Throughout his tenure of office, Francis was primarily concerned with meeting demands for increasing amounts of water power. He purchased the control of a number of the Merrimack River's water sources in central New Hampshire in 1846 in order to guarantee a year-round supply of water to Lowell. Two years later, Francis completed work on the Northern Canal, Lowell's largest and most complex waterway. It ran over four thousand feet from the head of Pawtucket Falls to the upper level of the Western Canal, and it greatly increased the power potential of Lowell's canal system. The more intricate canal system, however, increased the possibility of a flood in the city. Realizing this, Francis, in 1850, erected a huge wooden gate termed "Francis Folly" by his critics, at the Guard Locks on the Pawtucket Canal. "Francis Folly" proved its usefulness in the flood of 1852 when it prevented serious damage to Lowell and its canal system. In his forty years of service, James B. Francis had made major contributions to the science of hydraulics. His achievements have helped to provide Lowell with an efficient energy source for over a hundred years that can be appreciated in the present age of energy consciousness.

LOWELL'S FEMALE OPERATIVES

In their search for model workers and a reliable labor source, the "Boston Associates" recruited the daughters of Yankee farmers. Lowell's mills provided young New England farm women a respectable way to earn money and an opportunity to improve their lives. Hired by company agents, women came to earn dowries for future husbands, to help support their family's farm, or to become self-sufficient and independent.

Living in company boardinghouses, their lifestyles were controlled by strict company codes. A twelve-hour day and a six-day work week were normal. Every waking hour was regulated by a bell. Wages for female operatives were set at a rate of $2.25 to $4.25 per week with $1.25 deducted for room and board. The female operatives became an intrinsic part of the new community. They supported churches, schools, banks, lyceums, concerts and libraries; and from 1840 to 1845 the operatives edited and published The Lowell Offering, an early women's literary magazine.

Lowell became a major visitor attraction in the early nineteenth century. Numerous Americans, including Andrew Jackson and Davy Crockett, commented favorably on the factory system and its work force, as did a variety of European travelers ranging from Charles Dickens to political economist Michael Chevalier.

LABOR MOVEMENT

Although the manufacturing system at Lowell originally combined economic profit (for the mill owners) and agreeable working conditions (for the workers), improved technology and increased competition within the industry would later change the system which had once seemed ideal. By 1845, operators were working longer hours under deteriorating conditions and turning out more cloth at less pay than when the mills first opened.

Lowell witnessed its first strike in 1834, when women workers objected to a fifteen percent wage reduction. Though unsuccessful, it laid the foundation for the formation of such groups as the Factory Girls Association in 1836 and the Lowell Female Reform Association in 1847. Local and regional newspapers were also published grievances. The best of these papers, The Voice of Industry, was edited by Sarah Bagley and published by the Lowell Operatives.

In 1853, increasing workloads, hazardous conditions, improving technology, and decreasing wages led to a series of walkouts which resulted in the reduction of the work day from thirteen to eleven hours at Lowell and nearby Lawrence. Generally, however, walk-outs and other protests were unsuccessful in the face of the nearly inexhaustable labor supply provided by the number of immigrants in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

The first city-wide strike of textile workers was unsuccessful in 1903; though in 1912, the Industrial Workers of the World led workers to the achievement of a six to eight percent increase in wages. Lowell's labor problems declined along with the textile business itself after a revival following World War I. Some of Lowell's labor force was able to make the transition to working in other industries, but since newer industries could not employ workers on the scale Lowell had known previously, the labor force was generally dispersed.

ETHNIC DIVERSITY

Throughout its history Lowell has attracted successive waves of immigrants, who upon coming to Lowell, found unskilled jobs in abundance and companies eager to hire them at low wages. A pattern evolved. Each group would establish a community, erect a church, and build commercial and social institutions.

Irish workers were the first to arrive in Lowell. Led by Hugh Cummiskey in 1822, they walked from Boston in order to dig Lowell's canals and build its mills. They established a camp on an acre of land donated by Kirk Boott. The area quickly became known as the "Acre", and it was here that the first Catholic church, St. Patrick's, was built. It was in this area, too, that the first publicly financed parochial school was opened. As new opportunities developed, Irish families moved out of the "Acre" into the social and economic mainstream of the city.

In the 1860's and 1870's, increasing numbers of French-Canadians came to Lowell and began to fill many of the unskilled positions in the mills. Large tenements were soon erected in order to accommodate their housing needs in an area near the "Acre" known as "Little Canada." Lowell's first French-Canadian church, St. Joseph's, was located near the factories and downtown Lowell, The French-Canadian community established many civic, social and cultural institutions including a French newspaper, L'Etoile.

The first Greek people arrived in the 1880's. Over the course of the next twenty years, thousands of Greeks immigrated to Lowell. The "Acre" once Irish, became one of the largest Greek communities in the country. The Greek Orthodox Holy Trinity Church, a Byzantine styled Church completed in 1908, contained the first Greek parochial day school in America. Surrounding their church, the Greeks built a self-sufficient community, which included numerous schools, shops, and coffee houses.

Other significant groups of immigrants coming to Lowell included the Portuguese during the 1850's, an Afro-American community in the 1870's, European Jews in the 1880's, Poles a decade later. Armenians during the first part of the twentieth century, and Asians and Hispanics over the course of the last twenty years. Each of these groups has added to Lowell's ethnic diversity and each has enhanced the city's cultural heritage immeasurably.

BIRTH OF A PARK

As Lowell struggled with its declining economy in the middle of the twentieth century, "modernization" and urban renewal threatened to destroy the city's historic districts. Late in the 1960's though, a community based federal program, Model Cities, proposed to revitalize the city through the rediscovery of its heritage. The Lowell City Council adopted a resolution in response to this proposal in 1972 which designated an "historical park concept" as the focal point of future urban development.

The state, the city, and the local community strove to gain national support. In response to their efforts, Congress created the Lowell Historic Canal District Commission in 1975 which, in turn, prepared a plan for the "preservation, interpretation, development, and use of the historic, cultural, and architectural resources of the Lowell Historic Canal District."

Subsequent to Congressional approval, President Carter signed the law establishing Lowell National Historical Park and the Lowell Historic Preservation District on June 5, 1978. The National Park Service administers the Park and working in cooperation with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the City of Lowell, and other local and private organizations, is responsible for the preservation of certain historic structures and the interpretation of Lowell's history. The Lowell Historic Preservation District borders the Park and is administered by the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior.

INDEPENDENT WALKING TOURS

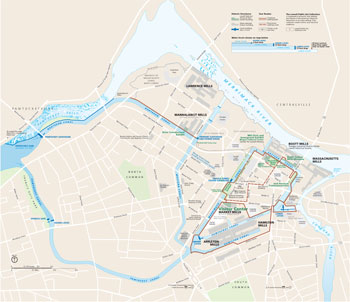

(click for larger map) |

While walking this tour route, please keep individual and family safety in mind, particularly when crossing streets. The tour involves ¾ of a mile (1 km.) walking and takes about an hour to complete.

LOWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

Founded in 1828, this corporation was one of the country's leading carpet manufacturing companies throughout the 19th century. The turn-of-the-century buildings which today house the National and State Park Visitor Center were recently rehabilitated to serve the city's present commercial and residential needs. Begin your tour here by viewing the Park's multi-image slide show and exhibits in order to orient yourself to the city and its past. Keep the five Park themes in mind as you walk the tour route.

SHATTUCK STREET

Located here you can see outstanding examples of the 19th century commercial architecture which evolved as Lowell diversified and grew up around the mills. The MACK BUILDING, built in 1886 as a pipe and stove manufacturing company, is now the home of the Lowell Heritage State Park's offices and exhibit areas. Built in 1844 and modified considerably since then, the WENTWORTH BLOCK was an important early commercial structure. The LOWELL INSTITUTION FOR SAVINGS was organized by the city's mill interests in 1829 to encourage thrift among Lowell's women workers; the bank has been located on this site since 1845. The LOWELL GAS LIGHT BUILDING, built in 1859, presently houses the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission's offices. The J.C. AYER BUILDING, nearby on Middle Street, was constructed in the 1890's and is a reminder that Lowell was once a mecca for the patent medicine business; the J.C. Ayer company was one of the industry's leading manufacturers.

MERRIMACK STREET

Along Lowell's major thoroughfare, you can see structures representing the many forces that shaped America's pioneering industrial city. Especially noteworthy is OLD CITY HALL, which served the community from 1830 until 1893, after which time its facade was rebuilt as it presently exists to serve downtown commercial interests. The building's scale contrasts dramatically with the present CITY HALL, which when constructed in 1893, represented the emergence of a mature city and strong municipal government free from the control of the textile corporations. The YORICK CLUB was built by the Merrimack Manufacturing Company in the 1860's and later became an exclusive men's club. Nearby are the Merrimack Canal and MOODY STREET FEEDER GATEHOUSE. The canal was dug by hand in the early 1820's to supply waterpower to the city's first great mill complex. The gatehouse was constructed 25 years later as part of a canal system improvement project that virtually doubled the amount of waterpower in Lowell. LUCY LARCOM PARK, located across the canal, is the site of weekly ethnic festivals and farmers' markets in the summer. The park is named after a "Mill Girl" and popular author and is the location of the BOSTON AND LOWELL RAILROAD MEMORIAL, a tribute to an industry which not only served Lowell's mill interests, but which Lowell's founders helped launch in the 1830's. ST. ANNE'S CHURCH was built in 1825 by the mill owners to ensure a proper moral environment for their workers—a key factor in the success of the Lowell experiment.

KIRK STREET

Once one of the most fashionable streets in Lowell, Kirk Street has changed noticeably over the years. Indicative of the street's (and city's) changing character is the 1881 primary school that became home for the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association. The Association served the Greek immigrants, who like other ethnic groups, came to work in Lowell's mills. Located at the end of the street, the KIRK STREET AGENTS' HOUSE remains from the neighborhood's earliest days. Constructed in 1845, this duplex was the home of the agents of the Boott and Massachusetts Mills and is an example of the conservative dignity in which company officials were once housed.

BOOTT MILL

One of the last of the major textile corporations to be organized in Lowell (1835), the BOOTT MILL, with its distinctive 1864 bell tower, is probably the best surviving example of mill architecture in the city. You can still see the main components of the Lowell factory system here, including the BOOTT MILL BOARDINGHOUSE, one of the 8 original buildings which housed the company's "mill girl" labor force; the EASTERN CANAL, the source of the company's water power; and the mill complex itself. Originally consisting of four simple mill buildings and a few smaller structures, the Boott Mill complex grew over the course of the next 80 years.

DOWNTOWN LOWELL

Located throughout the downtown are a number of historic structures, many of which have been rehabilitated as part of Lowell's recent revitalization. Please note the PAWTUCKET CANAL vista off of Central Street, which includes a view of the LOWER LOCKS, one of three control structures on the canal, and a dramatic view of the HAMILTON (1825), and the APPLETON MILLS (1828).

POINTS OF INTEREST

A. Bank Block (1826)

B. Whistler House (1825)

C. Old Market House (1837)

D. Corporation Boarding Houses (1839-1841)

E. St. Paul's Methodist Church (1826)

F. First United Baptist Church (1826)

G. Eliot Church (1830)

H. Holy Trinity Hellenic Orthodox Church (1908)

I. St. Patrick's Church (1854)

J. Guard Locks & Francis Gate

K. Suffolk Manufacturing Company (1831)

L. Lawrence Mfg. Company Agents' House (1833)

M. Old Stone Tavern (1824)

N. Frederick Ayer Mansion (1876)

0. Josiah Spalding House (1761)

P. Pawtucket Gatehouse (1848)

Q. St. Jean Baptiste (1892)

R. St. Joseph the Worker (ca. 1856-1878)

S. Mechanics Block (ca. 1840)

T. Massachusetts Mill (1839)

U. Hamilton & Appleton Mills (1826, 1828)

V. Lawrence Mill

W. Lower Locks

X. Auditorium

Source: NPS Brochure (undated)

|

Establishment Lowell National Historical Park — June 5, 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Proposal for an Urban State Park in Lowell, Massachusetts (August 1974)

A Proposal to Prepare: The Lowell National Urban Cultural Park Comprehensive Plan (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Anderson Notter Associates, Inc. and Economics Research Associates, October 15, 1975)

Boott Mills Exhibit Plan (June 29, 1987)

Canal Development and Hydraulic Engineering: The Unique Role of the Lowell System (Patrick M. Malone, April 26, 1974)

Details of the Preservation Plan (Lowell Historic Preservation Commission, 1980)

Ethnicity in Lowell: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Lowell National Historical Park (Robert Forrant and Christopher Strobel, March 2011)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Lowell National Historical Park, Massachusetts (August 1981)

Foundation Document, Lowell National Historical Park, Massachusetts (September 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Lowell National Historical Park, Massachusetts (January 2017)

Future Directions, Lowell National Historical Park (Michael Creasey, September 20, 2005)

Historical Data Section: Jade Pagoda and Solomon Sites, Lowell, Massachusetts (Robert Weible, Winter 1980)

Historic Districts Study Committee Final Report, Lowell, Massachusetts (1973)

Historic Landscape Assessment for Eastern Mill Yard, Boott Cotton Mill No. 6, Lowell National Historical Park (March 1995)

Historic Structure Report-History Portion: Building 6; The Counting House; The Adjacent Courtyard; and the Facades of Buildings 1 and 2, Boott Mill Complex, Lowell National Historical Park, Lowell, Massachusetts (Laurence F. Gross, 1986)

Historic Structure Report: Kirk Street Agents' House, Lowell National Historical Park, Lowell, Massachusetts (Maureen K. Phillips, 1997)

Historic Structure Report: Lowell Old City Hall, Historic Data Section (Harlan D. Unrau, January 1982)

Historic Structure Report: United First Parish Church (Unitarian) Church of the Presidents, Quincy, Massachusetts (Peggy A. Albee, Richard C. Crisson, Judith M. Jacob and Katharine Lacy, April 1996)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Lowell National Historical Park (2011; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book (Book A), Lowell National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Lowell: The Early Years 1822-1840 (Thomas Dublin, April 26, 1974)

Lowell: The Spindle City — Historic Resource Study, Lowell National Historical Park (Stephanie Fortado and Emily E. LB. Twarog, September 2023)

Lowell: The Story of an Industrial City NPS Handbook 140 (1992)

Mister Magnificent's Magical Merrimack Adventure! (©Ingrid Hess, 2016)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

City Hall Historic District (Christine Boulding and Bob Malavich, February 24, 1975)

Lowell Locks and Canals Historic District (George R. Adams, June 1977)

Lowell National Historical Park (Robert Weible, June 1985)

Old City Hall, Lowell, Massachusetts, and Its Surrounding Properties (Robert Weible, Spring 1979)

Preservation Plan (Lowell Historic Preservation Commission, 1980)

Preservation Plan Amendment (Lowell Historic Preservation Commission, 1990)

Proposal for a Comprehensive Plan: Lowell National Urban Cultural Park (Sasaki Associates, Inc., Benjamin Thompson and Associates, Inc., Gladstone Associates and Research and Design Institute, 1975)

Report: Lowell National Historical Park and Preservation District Cultural Resources Inventory (Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott, 1980)

The Lowell Park Trolley, Development and Implementation (Nancy Bellows Woods, April 18, 1986)

The Power Cannels of Lowell, Massachusetts (Larry D. Lankton and Patrick M. Malone, October 1973)

The River and Its City: An Outline of the History of Lowell, Massachusetts (1980)

The Working People of Lowell, Oral History Collection, Oral History Collection, Lowell National Historical Park

Esther Alfano (interviewed by Paul Page, November 5, 1985)

Madeline Bergeron (interviewed by Pat Coble, November 1, 1985)

Dana Quinones (interviewed by Sylvia Contover, August 1, 1986)

Florie Hamm (interviewed by Suzette Jefferson, October 26, 1985)

Edward Huntley (interviewed by Joan Walsh, October 27, 1985)

Elmer Rynne (interviewed by Paul Page, June 16, 1986)

Roland Larochelle (interviewed by Olga Spandagos, December 10, 1985)

Irene Desmarais (interviewed by Sylvia Contover, November 12, 1985)

Mary Podgorski (interviewed by Olga Spandagos, November 14, 1985)

Edward Harley (interviewed by Paul Page, October 29, 1985)

Henry Pestana (interviewed by Olga Spandagos, October 26, 1985)

Lucy Rivera (interviewed by Paul Page, June 26, 1986)

Joseph Golas (interviewed by Suzette Jefferson, November 21, 1985)

Leona Pray (interviewed by Juliette Bistany, October 25, 1985)

John Graham (interviewed by Sylvia Contover, August 8, 1986)

Edward Huntley (interviewed by Joan Walsh, October 27, 1985)

Elmer Rynne (interviewed by Paul Page, June 16,1986)

Roland Larochelle (interviewed by Olga Spandagos, December 10, 1985)

Anita Wilcox Lelacheur (interviewed by Sylvia Contover, October 22, 1985)

Grace May Burke (interviewed by Suzette Jefferson, November 7, 1985)

Paul Page and Donna Mailloux (interviewed by Mary Blewett, August 6, 1986)

Alexandra Freitas (interviewed by Olga Spandagos, October 30, 1985)

John R. Falante (interviewed by Paul Page, November 20, 1985)

Sylvia Contover (interviewed by Pat Coble, October 10, 1985)

Cornelia Chiklis (interviewed by Sylvia Contover, January 16, 1986)

Urban Design Study, Lowell Community Renewal Program (October 1970)

Visitor Use Patterns and Interpretive Effectiveness in Two Urban Historical parks: Boston and Lowell, Massachusetts (April 1986)

Water Power in Lowell, Massachusetts (Patrick M. Malone and Larry D. Lankton, April 26, 1974)

lowe/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025