|

MAMMOTH CAVE

Hovey's Hand-Book of the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky |

|

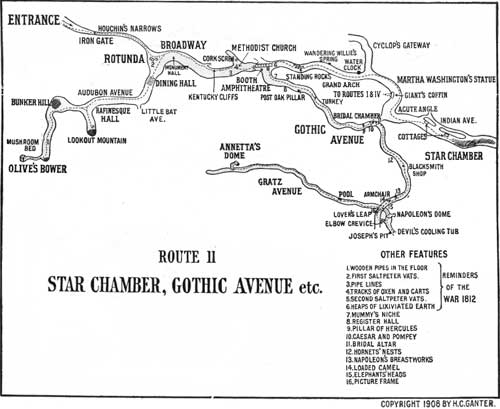

ROUTE II

Olive's Bower, Star Chamber, and Gothic Avenue

After a suitable period of rest and refreshment at the Hotel we resume our way along the same path taken for the first route, but presently deviate to explore Audubon Avenue, of which we had only seen the beginning. It is related that when the great ornithologist visited Rafinesque, the former smashed a fine violin in his eagerness to capture a unique specimen of the bat family. As a kind of amicable revenge the latter affixed Audubon's name to this avenue, where so many myriads of bats annually hibernate. It is fitting that the great branch to the left, sweeping for three hundred and fifty feet and suddenly ending in a tumble-down, should be named Rafinesque Hall. Unless our visit is in late fall or winter, we find but few clusters of bats; but in cold weather they gather here from near and far and hang head-downward till somehow, by a sense not explained, they know it is warm weather out-of-doors, and then fly forth to the forests. Dr. Call boasts of a single catch that gave him six hundred and seventy bats, of many varieties, most of which were sent to the National Museum.

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

Advancing through Audubon Avenue, we soon find the roof and floor approaching to form what is called Bunker Hill, around which we pass by a narrow defile. The Mushroom Beds attract our attention, to which we have already referred as having cost far more than they ever returned by way of profit, although the idea itself is feasible.

Above a floor encumbered by debris hang formations needing an explanation. Limpid drops trickle through the roof, saturated with bicarbonate of lime. The supply of water is constant, but so meager as to drip instead of flow; and as the dripping goes on each drop lays down its load as a ring slight enough for a fairy's finger. Ring follows ring till a pendant is formed like a pipestem. The pipestems thicken to the size of candles, and often grow as large as tree-trunks. Occasionally they broaden into elegant drapery, or are twisted into fantastic shapes. All these stone icicles are called "stalactites."

Such lime-laden drops as fall splash about and on evaporation deposit, not rings, but films thin as tissue-paper, building up stalagmites that are solid from their base upwards. Often these downward and upward growths meet as stately shafts, like the pillar named the Sentinel, which guards Olive's Bower a few steps beyond it.

The general term "dripstone" is conveniently applied to all these deposits, and their finer varieties are known to the mineralogist as "oriental alabaster." A central stalactite in Olive's Bower is very large and cone-shaped, amid many smaller ones. Below is a rampart, looking over which we see, some twenty feet below, a limpid pool that reflects the overhanging formations. Before leaving the subject of dripstone it should be remarked that, chemically regarded, it is simply the hard carbonate, not the bicarbonate, as is often alleged; the latter being an unstable compound, readily changing on any change of its conditions.

The pit which arrests our progress beyond Olive's Bower might, if explored, prove this locality to be connected with White's Cave, whose features it resembles. On returning to the Rotunda we again inspect the historic relics of the War of 1812, and mark the grooves cut in the limestone walls by the hubs of the primitive cart-wheels that were slowly drawn along by oxen to collect the nitrous earth for the saltpeter vats. We notice that the bottoms of these vats were made of small logs halved and grooved and laid in layers on supports; the lower layer with its grooved surface up, to receive the second layer in reversed position, making a method for conveying the lye into reservoirs, whence it was pumped out to the crystallization troughs. Dr. Call was the first to direct attention to this ingenious device.

Again we forsake the Main Cave for a ramble through Gothic Avenue, which is reached by a stairway just beyond the vats. At the entrance to it is Booth's Amphitheatre, where Edwin Booth is said to have recited a part of the play of Hamlet. In early times a mummy was found in an adjoining cave, and brought hither for exhibition. The alcove where it reposed still bears the name of the Mummy's Niche. It was afterward carried about through the West on exhibition, and it was the writer's privilege to see it at that time, It was naturally dessicated, and with its ornaments and garments was regarded as a great curiosity. It remained in a museum at Worcester, Mass., for many years, and is now in the National Museum at Washington, D. C.

Hundreds of visitors have recorded their names in Register Hall, either by scratching them on the wall with the knife or smoking them there by their candIes, or else by the less conspicuous way of depositing their cards on the ledge set apart for that purpose. Here, and also in parts of the Main Cave, so-called "monuments" are built by piling up flat fragments of stone in honor of individuals, States, or benevolent organizations; a practice which incidentally has helped to clear obstructions from the pathway in which we walk. The largest of them all is quite properly the Kentucky Monument. The effect in general, however, is to divert attention from the natural attractions.

The hoary old stalactites, great and small, in Gothic Avenue got their growth ages ago. The signs show that long ago the Cave stream was diverted to lower channels, leaving the place as dry as a tinder-box. The Post-Oak Pillar, the Pillars of Hercules, Pompey and Caesar, and the Altar in Gothic Chapel, are interesting and picturesque, and give the guides occasion for many legends and jokes; but do not warrant the conclusions drawn by Dr. Binkerd and others as to the age of the Mammoth Cave, judging by the alleged slow growth of dripstone in a locality where there is now no growth at all. There is no doubt as to the vast antiquity of the great cavern, whose remote origin is by many referred to the Tertiary Period; but it must be remembered that geological changes are by no means uniform, and that catastrophe has evidently played a conspicuous part in cave-making.

There is not enough moisture now in Gothic Avenue to make the atoms float in the air. Toss a handful of dust up, and it falls back like so much shot. I saw a party of young people who came here directly from the ballroom, and not a particle of dust spotted the trailing robes or clung to the polished boots. Wood here undergoes tardy decay, and fresh beef and other meats keep sweet for a long time, and then dry up like the old mummy which was mentioned as having once been placed here.

Pompey's Pillar is named for a negro miner, a raw hand, who in old times trudged in here alone for "peter-dirt" and lost his way. He stumbled, put out his lamp, and was in a frenzy. When at last he saw his half-naked negro comrades approach, swinging their torches and shouting, he took them for demons, and shouted lustily for mercy. It took no little shaking and punching to convince him that he was yet alive and in Mammoth Cave, instead of elsewhere.

It may tax the imagination to find the resemblance to an Elephant's Head in the stalactite so called; but once found the grotesque likeness is vivid.

|

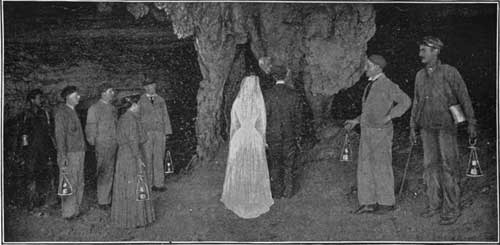

| Marriage in "Gothic Chapel" |

A curious legend told of the Gothic Chapel and its Bridal Altar is verified. A Kentucky belle gave her heart to a gallant Southron. But her mother, who opposed the match, made her swear never to marry any man on the face of the earth. Shortly the lovers eloped and were hotly pursued; but before they were caught they were married in this novel Gretna Green. Taxed with her broken pledge, the bride replied: "Mother, dear, it was not marrying any man 'on the face of the earth' to wed my own true love in this underground chapel."

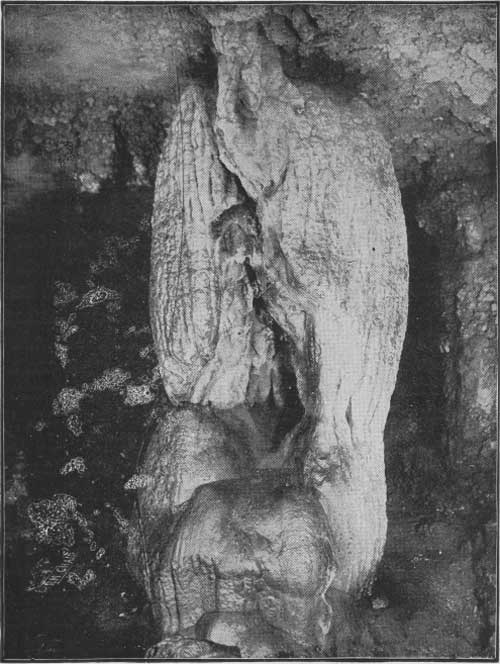

Few ladies fail to rest awhile in the Old Arm Chair, a stalagmite naturally fitted as a seat. Jenny Lind sat here and sang one of her sweet songs; and many a song has been sung here since. A slender projection beyond it is called the Lover's Leap, from whose point an illumination shows a wild mass of rocks amid which runs a narrow path styled the Elbow Crevice, whose walls are fantastically folded. We escape from the ragged edge of what is known as Joseph's Pit, and note in passing the Devil's Cooling Tub - Gatewood's Dining-Table is a huge flat rock directly under Napoleon's Dome, from whose apex it fell.

Gratz Avenue, into which we enter, is not on the same Cave level as the Gothic Avenue. Unless we take care we may walk directly into the exquisitely clear waters of Lake Purity, a small mirror-like pool. Beyond it we go, winding to and fro, till at the foot of a small cliff we find the entrance to Annette's Dome, one of the prettiest in all the Cave. Shaler's Brook spouts from the wall and runs merrily and musically into a smaller room, whence it vanishes, falling by a leap of seventy feet into Lee's Cistern. In Gratz Avenue are found blind crustaceans, crickets, and other forms of life described by Dr. Call.

|

| "Old Arm Chair" |

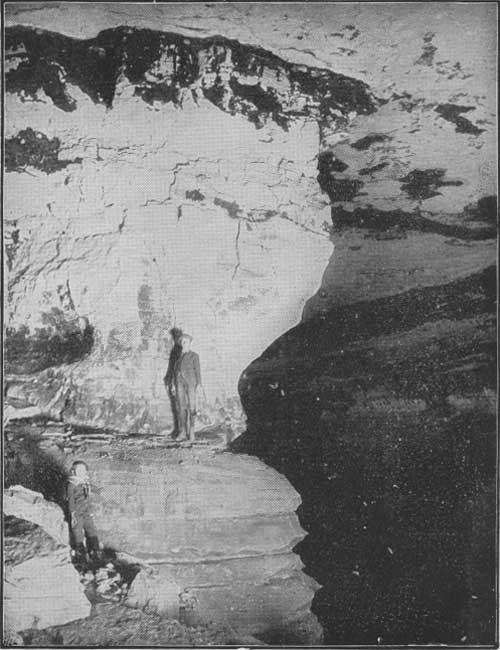

We now retrace our way to the Main Cave, passing various objects noticed in the first route. Shortly beyond the Giant's Coffin the Main Cave turns suddenly to the left at the Acute Angle, where the burning magnesium makes visible the vast dimensions of the cavern by illuminating it in two directions at once. A village in the vicinity formerly sheltered a colony of consumptives who, in 1843, and by medical advice, took up their abode here, hopeful for relief or cure because of the uniform temperature and the naturally oxygenated air. The sunless days passed slowly by till the pitiful experiment was abandoned as a failure, as was also the experiment by the invalids to make trees and shrubbery grow around their dismal huts. Some of the victims of the "white plague" lie buried in the grove back of the Hotel garden, while others died soon after returning to their homes. There were originally thirteen cottages and tents, the only ones now remaining being two roofless stone structures beyond the Acute Angle.

A strangely beautiful transformation scene is wrought for us in the Star Chamber, a hall seventy feet wide, sixty feet high, and several hundred feet long. The ceiling is coated with manganese dioxide, and through this black background emerge hundreds of brilliant white stars, made by the efflorescence of the sulphate of magnesia. These are invisible at first, and the magnificent archway sweeps above us in midnight blackness. Long benches are ranged against the right-hand wall, on which the guide seats us, while he collects our lamps and vanishes with them behind a jutting rock. Then comes the marvelous illusion. The roof seems lifted to an immense height. Indeed, we seem to gaze from a cañon directly up to the starry sky. Cloud-shadows are thrown athwart it by adroit manipulation. A meteor shoots across the vault. We behold the mild glory of the Milky Way. Suddenly the guide breaks in upon our exclamations of delight by saying, "Good night. I will see you again in the morning!" He plunges into a gorge. We are in utter darkness. The silence is so perfect that we can hear our hearts beat. Presently a glimmer comes from another direction, like a faint streak of dawn. The aurora tinges the tips of the rocks; the horizon is bathed in a rosy glow; a concert of cock-crowing, the lowing of cattle and other barnyard sounds, answered by the barking of the house-dog, seem to herald the rising sun; when the ventriloquial guide appears, swinging his cluster of lamps and asking how we liked the performance. Our response is a hearty encore; after granting which the guide tells us that the second route ends here, and he must pilot us back to the mouth of the Cave and to the Hotel. Those who have witnessed the wonders of the Star Chamber many times testify that the charm never wanes.

|

| "The Acute Angle" |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hovey/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Dec-2011