|

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

Turning nickels into dollars

In 1901 Maggie Lena Walker boldly presented her community with an idea for economic empowerment: "We need a savings bank, chartered, officered, and run by the men and women of this Order..... Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars." In 1903 St. Luke Penny Savings Bank opened its doors—the first chartered bank in the United States founded by a black woman. Today it thrives as the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, the oldest continually operated African American bank in the United States.

Maggie Mitchell was 14 when she joined the local Independent Order of St. Luke. Founded in 1867, this benevolent society aided African Americans in times of illness, old age, and death. In 1899 she was elected Right Worthy Grand Secretary of the national Independent Order of St. Luke and transformed the struggling order into a successful financial organization with her sound fiscal policies and genius for public relations.

All her life Maggie L. Walker spoke out for equal rights and fair employment, especially for women. She worked alongside Mary McLeod Bethune and W.E.B. Du Bois and served on the boards of local and national civic organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Despite humble beginnings and personal tragedies, Mrs. Walker achieved national prominence and respect for her business and humanitarian accomplishments.

1867-1869

Born July 15, 1867 (although some records indicate 1864 or 1865), in

Richmond, Va., to Elizabeth Draper, a former slave and servant in

Elizabeth Van Lew's home, and Eccles Cuthbert, a white journalist and

Confederate soldier; Draper marries William Mitchell, Miss Van Lew's

butler.

1876-1878

Helps mother by collecting and delivering laundry to white customers and

observes disparate economic opportunities for blacks and whites; attends

school; is baptized in First African Baptist Church.

1881-1883

Joins Independent Order of St. Luke (I.O. of St. Luke); protests

inequality of white and black graduation ceremonies by participating in

a black student school strike, the first such response in the U.S. to

unequal treatment; teaches elementary school; studies accounting at

night.

1886-1888

Marries Armstead Walker Jr, a brick contractor; leaves teaching;

continues activities with I.O. of St. Luke.

1890-1894

Son Russell Eccles Talmage born 1890; son Armstead Mitchell born 1893

(dies at seven months).

1895-1897

Establishes juvenile branch of I.O. of St. Luke; becomes Grand Deputy

Matron of the branch; son Melvin DeWitt born 1897.

1899

Elected Right Worthy Grand Secretary of St. Luke, its highest rank

(later becomes Secretary-Treasurer); retains position until 1934.

1901-1905

Establishes newspaper, St Luke Herald, 1902; charters St. Luke

Penny Savings Bank, 1903, is president until 1931; moves to 110½

East Leigh Street; establishes the St. Luke Emporium, a retail

store.

1915

Husband Armstead accidently killed.

1921

Runs unsuccessfully with John Mitchell on "Lily Black" ticket: he for

Virginia's governor, she for superintendent of public instruction.

1923-1927

Receives honorary Masters degree from Virginia Union University; son

Russell dies.

1928

Confined to wheelchair by paralysis.

1934

Dies in Richmond on December 15 of diabetic gangrene; is buried at

Evergreen Cemetery.

Maggie L. Walker

Maggie L. Walker was already famous as a dynamic leader in Richmond's black community when she and her family moved to 110½ East Leigh Street in 1905. She had devoted over 20 years to the Independent Order of St. Luke and had founded a newspaper and chartered a bank. Community service and professional success, however, were only part of Mrs. Walker's philosophy for what constituted a full life. She believed that success sprang not only from thriftiness and hard work, but from a commitment to her faith and her family.

Maggie Mitchell joined the First African Baptist church at age 11, and she was inspired by the members who prayed and worked together to uplift their community. Throughout her life she studied the Bible, participated in church activities, and quoted scripture in her writings and speeches.

Her stepfather died when she was nine years old, thrusting the family further into poverty. She worked hard helping her mother, who supported them by taking in laundry. The poverty and daily struggle taught her self-sufficiency and how to deal with tragedy and hardship.

Maggie attended public school in a racially segregated system. The inequity was most apparent during her 1883 graduation from the Colored Normal School, when the graduation facilities offered to blacks were inferior to those used by whites. Maggie's class staged a boycott, possibly the first school strike of the civil rights movement. After graduation Maggie taught elementary school for three years. In 1886 she married Armstead Walker Jr. and retired from teaching as required by Virginia law. The change allowed her to direct her energies toward strengthening the Independent Order of St. Luke and caring for her growing family. In time. Walker's boundless devotion to her work and family rewarded them with financial and social success.

Tragedy struck in 1915 when Armstead was accidently killed, leaving Mrs. Walker to manage a large household. Her investments and hard work kept the family together. The family expanded again when her sons Russell and Melvin married and brought their wives to live at home, where four grandchildren were born. As the family grew, the house grew too—finally to a 28-room complex that all but covered the 33- by 139-foot lot. In 1928 paralysis confined Mrs. Walker to a wheelchair. Undaunted, she added an elevator to the house and altered her car and desks to accommodate the wheelchair.

Maggie Lena Walker died at home on December 15, 1934. Nationally, she was acclaimed as a champion for oppressed blacks and women.

In Richmond she was mourned as a leader who dedicated her life to family and uplifting her community.

110½ Leigh Street

1883 The two-story Victorian house with Italianate detailing began with seven rooms.

1890s Robert Jones, a black physician, built rooms and the west wing for a waiting and examination area.

1904-22 Walker converted gas lights to electric, added central heating, a cellar, 12 rooms, and the two-story porch.

Planning Your Visit

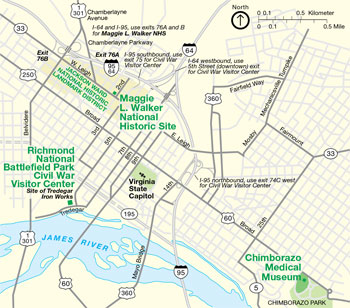

(click for larger map) |

Visitor Center

All activities and tours begin at the visitor center at 600 N. 2nd

Street. Here you will find information, exhibits, and a short video. A

bookstore offers publications and items about Maggie L. Walker and

African American culture. The visitor center and house are open Monday

through Saturday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; they are closed Thanksgiving,

December 25, and January 1.

Guided House Tours

The only way to see the house is with a guide; there is no fee. Tours

leave the visitor center every half hour; the last tour begins at 4:30

p.m. A limited number of persons are allowed on each tour, and there may

be a waiting period. You may see the film, the courtyard, and other

buildings until your tour begins. Group tours require advance

reservations; call ahead.

Special Programs

The park offers activities all year. A highlight is the annual birthday

celebration for Maggie L. Walker on or about July 15.

Accessibility

The visitor center, courtyard, restrooms, and first floor of the house

are accessible for visitors with disabilities.

Safety

Use caution when touring the site. Stairs are steep and

narrow—please watch your step. Smoking is not allowed. All historic

and natural features are protected by federal law.

Administration

The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site was designated in 1978 as

part of the National Park Service. It honors Maggie L Walker's

leadership in business that fostered opportunity for blacks and for

women.

Getting Here

From I-95 north/I-64 west: take exit 76A (Chamberlayne Parkway); turn

left at the light onto Chamberlayne; turn left onto West Leigh St.; go

2½ blocks to the park at 110½ East Leigh St. From I-95

south/I-64 east: take exit 76B (Belvidere); turn left at the stop light

onto Leigh St. and go 7½ blocks to the park.

Limited vehicle and bus parking is available on Second Street.

Visiting Historic Jackson Ward

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Richmond's Jackson Ward was one of

the most prosperous black communities in the United States. Here, blacks

owned and operated banks, insurance companies, retail stores, theaters,

and commercial and social institutions. Known as the birthplace of

African American entrepreneurship, today this area is one of the

nation's largest National Historic Landmark Districts associated with

black history and culture.

You can enjoy a walking or driving tour of Jackson Ward that highlights important sites, including the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, 110½ E. Leigh St.; Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia, 00 Clay Street; and the Bojangles monument at the intersection of Chamberlayne Parkway, Leigh, and Adams.

Source: NPS Brochure (2006)

|

Establishment Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site — November 10, 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

An Orientation: Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site (Celia Jackson Suggs, 1995)

Finding Aid: Maggie Lena Walker Family Papers, 1854-1970 (bulk dates 1900-1935) (Jennifer H. Quinn, February 1999; Ethan Bullard and Margaret Welch, revised February 2016)

Finding Aid: Right Worthy Grand Council, Independent Order of St. Luke Records (undated)

Foundation Document, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia (June 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia (January 2017)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia (September 1982)

Historic Furnishings Report: Maggie L. Walker House — Volume 1: Historical Data, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Richmond, VA (Ellen Paul Denker, 2004)

Historic Furnishings Report: Maggie L. Walker House — Volume 2: Implementation Plan, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Richmond, VA (Ellen Paul Denker, 2004)

Housekeeping Plan, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site (Brigid Sullivan, January 2010)

Interior Paint Analysis, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, 110 1/2 East Leigh Street, Richmond, Virginia (November 1999)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site (2016; for reference purposes only)

Long Range Interpretive Plan, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site (May 1998)

Maggie L. Walker Oral History Project: Volume I (Diann L. Jacox, October 1986)

Maggie L. Walker Oral History Project: Volume II (Diann L. Jacox, October 1986)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Maggie L. Walker House (Marcia M. Greenlee, December 1974)

Maggie Walker House (Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff, April 1975)

St. Luke Building (Bryan Clark Green, July 2018)

Ransom for Many: A Life of Maggie Lena Walker (Gertrude Woodruff Marlowe, 1996)

State of the Park Report, Maggie Walker National Historic Site, Virginia State of the Park Series No. 20 (February 2015)

The Jackson Ward Historic District (Robert P. Winthrop, 1978)

The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site: An Administrative History (Megan Taylor Schockley, August 2022)

mawa/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025